Allergic rhinitis (AR), non-allergic rhinitis (NAR), chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP), and chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps (CRSsNP) occur frequently in asthmatic patients. We evaluated nasal symptoms and nasal endoscopic findings in patients with asthma and correlated them to asthma severity.

MethodsSubjects (n=150) with asthma completed questionnaires designed to provide information related to asthma and nasal disease. Patients were divided into four groups based on asthma severity. Pulmonary function tests, skin-prick tests (SPTs) and nasal endoscopy were performed on every patient. Clinical findings were compared in asthma patients by rhinologists.

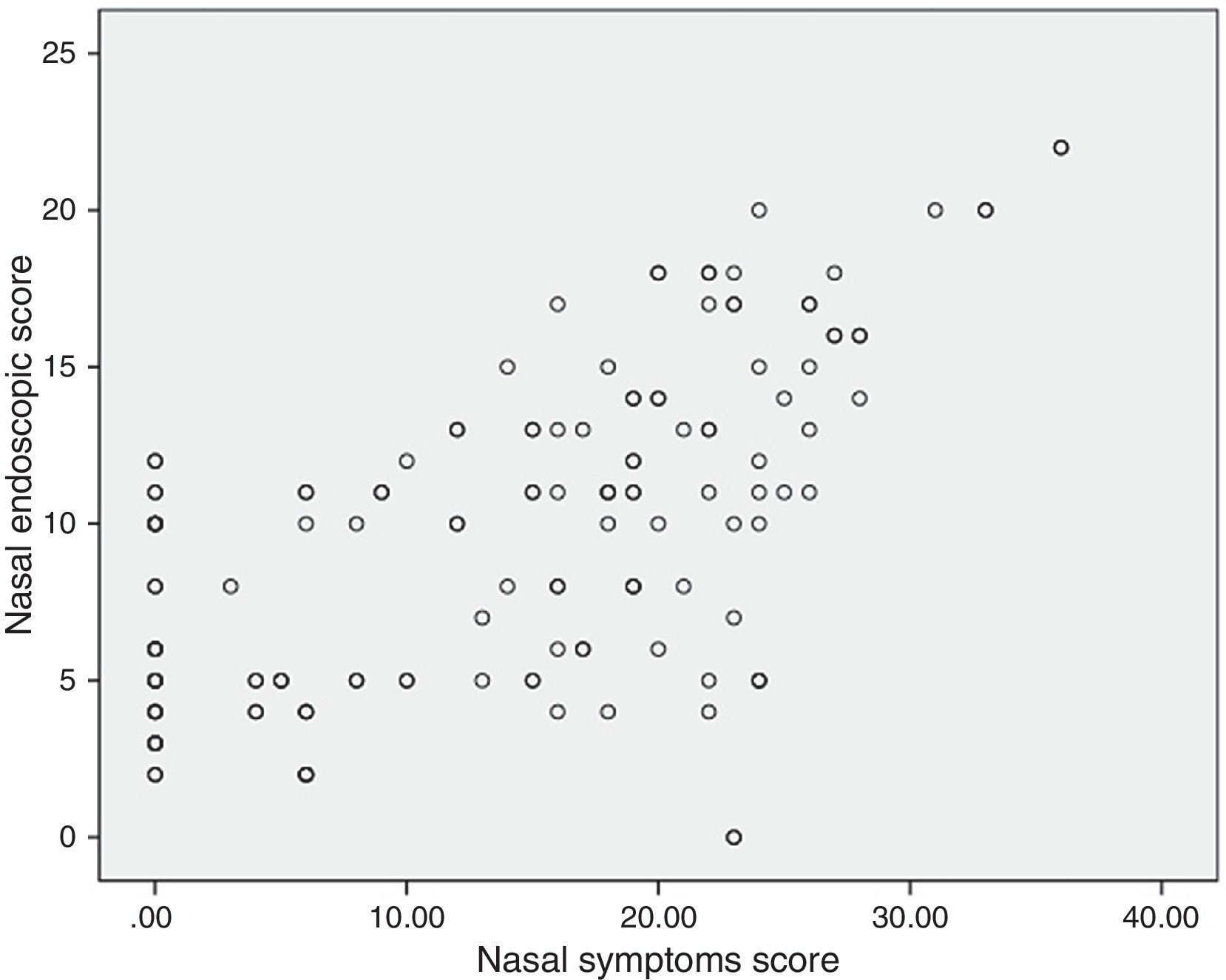

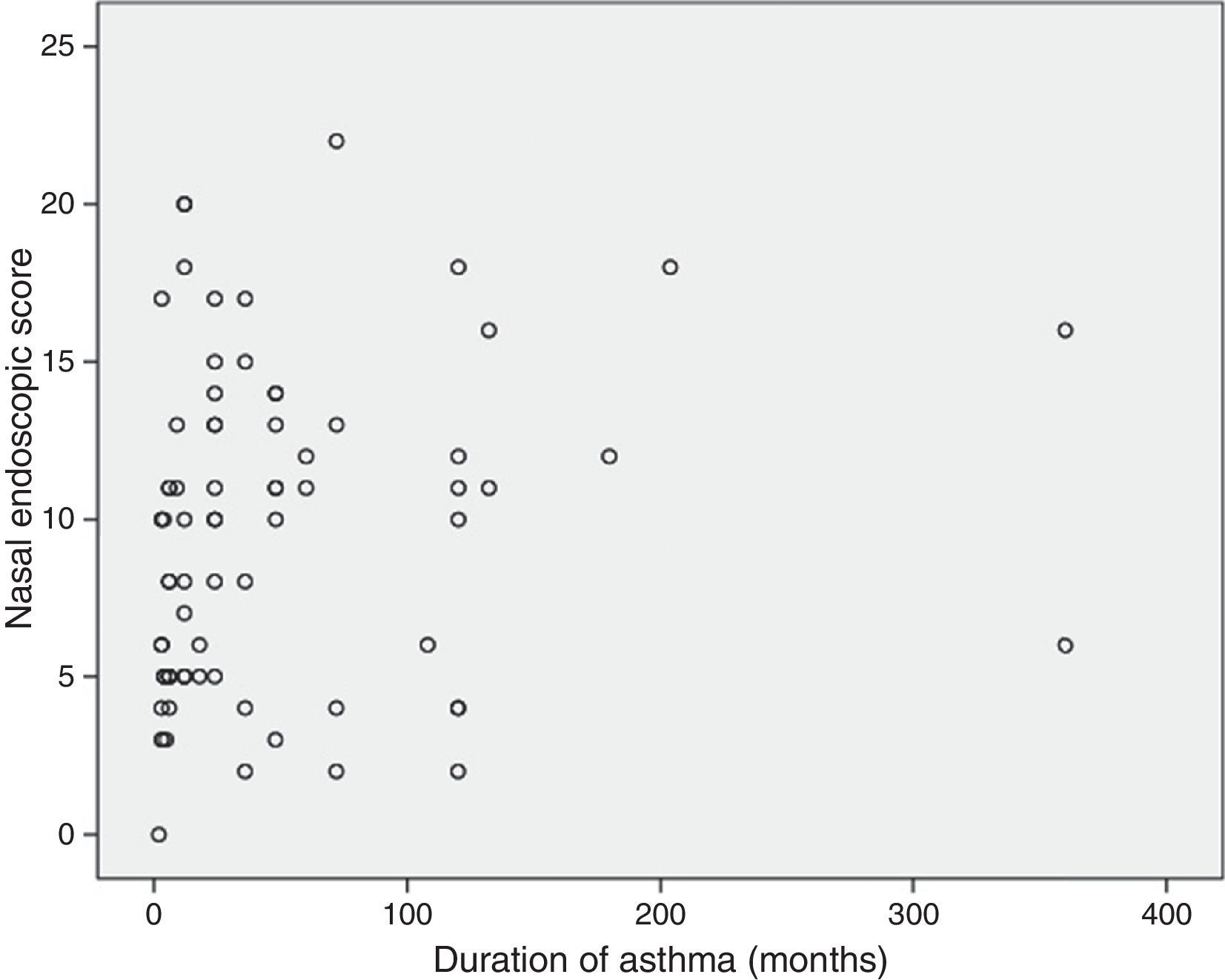

ResultsThe total incidence of AR, NAR, CRSwNP and CRSsNP in these patients with asthma was 76%. By using Fisher's Exact Test, there was no statistical significance between asthma severity and the incidence of AR, NAR, CRSwNP and CRSsNP (P=0.311). There was a significant difference in the total nasal symptoms score among subjects with different grades of asthma (P=0.002). However, there were no significant differences in the total Lund–Kennedy endoscopic score (LKS) (P=0.736). The nasal endoscopic scores were significantly correlated at a high degree with the nasal symptoms score (P=0.000). A significant correlation was found between the nasal endoscopic score and the duration of asthma in the patients with different grades of asthma (P<0.05).

ConclusionsThe relationship between rhinitis and asthma is complex. Nasal airways should become part of standard clinical assessment and follow-up in patients with asthma.

A large body of evidence from clinical epidemiology, pathophysiology, histology, and treatment outcomes supports the concept of a unified airway in which signs of disease in one part of the respiratory tract should be considered a disease of the whole. This concept is sometimes expressed as “one way, one disease”.1

Clinical observations show that the vast majority of patients with asthma have nasal disease. Unfortunately, when examining all available data, the prevalence of rhinitis in asthma ranges tremendously, from 6.2% to 95%.2–8 The explanation behind this wide variability is that there is little standardisation as to the types of questions that need to be asked for establishing the diagnosis of nasal disease. Many epidemiologists use similar tools as in asthma, primarily a positive response to the question of whether their surveyed subjects were given a diagnosis of allergic rhinitis or hay fever by a physician/paediatrician. However, patients with rhinitis are notoriously unaware of such diagnoses, primarily because their physicians ignore the presence of nasal disease. Actually very few physicians lay emphasis on nasal disease and refer their asthmatic patients to the otolaryngologist, due to limitations of their profession. The correlation among the subjective nasal symptoms in asthmatic patients, the representation of nasal mucosal inflammation and the severity of asthma are seldom investigated from a rhinological perspective.

Nasal endoscopy, with rigid and flexible instruments, is a traditional standardised technique and used regularly by otolaryngologist for diagnostic and surgical aims. Nasal endoscopy provides reliable visualisation of all the accessible areas of the nasal cavity and the representation of nasal mucosal inflammation. It is a useful and practicable technique after an appropriate local topical anaesthesia, since it offers the possibility of an in situ examination for numerous nasal structures.

Our principal aims were to demonstrate that nasal endoscopy may be easily feasible and necessary in asthmatic patients, and to evaluate nasal symptoms and nasal endoscopic findings in patients with asthma and correlate them to asthma severity.

Materials and methodsOne hundred and fifty adult asthmatic subjects were recruited from the outpatient clinic of the pneumology department in the Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University, China. A detailed clinical history and a complete physical examination, including allergy evaluation, were carried out by a respiratory physician and a rhinologist for each patient. Diagnosis of asthma was supported by: (1) affirmative answers to the following questions: “In the past 12 months, have you experienced wheezing or whistling in your chest?” or “In the past 12 months, have you taken any asthma medication?” (2) a positive bronchodilator test (minimum 12% relative improvement in the volume FEV1 after bronchodilator administration) and/or a prior positive methacholine challenge test (PC20<16mg/ml) when available. Asthma severity, in accordance with GINA criteria,9 was ascertained by the patient's level of symptoms and his/her level of treatment. Moreover, pulmonary function tests (spirometry) were carried out on each patient using the same equipment and the data were recorded in detail.

According to GINA criteria,9 inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) are the most effective controller medications currently available. Reliever medication (such as short-acting ¿2-agonist) should be provided for quick relief of symptoms as needed. Control of the disease was assessed by measuring daytime symptom frequency, night-time awakenings, interference with normal activity, and the peak expiratory flow rate.

We excluded all patients who met the following exclusion criteria: use of antibiotics, nasal corticosteroids, and nasal/oral antihistamines within the previous two weeks. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and informed oral consent was obtained from the patients.

Current symptoms of nasal blockage, secretion, itching and sneezing were rated on a 0–10 visual analogue scale (VAS, 0 – no symptoms, 10 – worst possible symptoms). An aggregate of the four symptom scores was calculated (total score).

The nasal endoscopic examinations were performed with rigid nasal endoscopes. The images were recorded with a camera for documentation. White balance was successfully performed for each evaluation in a consistent fashion. The Lund–Kennedy endoscopic score (LKS) was used to rank the subjective appearance of the nasal endoscopy10 before and after decongestion. The items for measurement included polyp, oedema, discharge, scarring, and crusting. The possible scores for each side were 0–10, and the total ranged from 0 to 20. Nasal endoscopy findings and the LKS scores were evaluated independently by two physicians who were unaware of the patients’ history.

Allergic rhinitis (AR) was diagnosed in patients with at least one sensitisation clearly related to the actual symptomatic period of the year, or associated with exposure to particular antigens; endoscopic representation is characterised by swelling or pale nasal mucosa; allergic sensitisation was assessed using skin-prick tests (SPTs) with a panel of 14 inhalant standard allergens. Non-allergic rhinitis (NAR) similarly has the symptoms of nasal congestion, rhinorrhoea, sneezing and sometimes the same endoscopic feature as AR but without positive SPTs. Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is clinically defined as an inflammation of the nose and the paranasal sinuses for >3 months characterised by two or more symptoms including nasal blockage, anterior or postnasal drip, facial pain or pressure, and a reduction in or loss of smell. Furthermore, together with the symptoms, there must be identifiable endoscopic signs. Depending on the endoscopic finding, CRS was divided into two categories: chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) and without nasal polyps (CRSsNP).

Statistical analysisThe data regarding the four groups of patients with different grades of asthma were compared using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test. The correlation analysis was accomplished using the Spearman rank test. The frequency analysis of nasal symptom score and endoscopic score distribution were obtained using the ¿2 test. Results are expressed as means and standard deviation. An overall P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

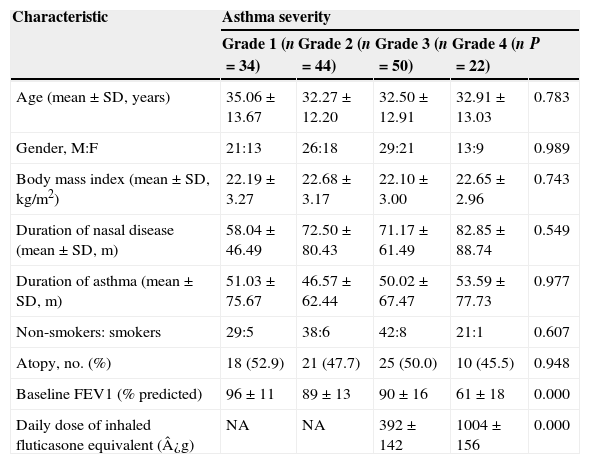

ResultsSubjectsOne hundred and fifty patients were evaluated consecutively, 89 males and 61 females, with an average age of 33.07 years (range 12–55 years). 122 patients (81.3%) were abnormal in pulmonary function test, 109 patients (72.7%) had a positive result in bronchodilator test and 49 patients (32.7%) had a positive result in methacholine challenge test. Among all the asthmatic patients, there were 34 (22.7%) with mild intermittent asthma, 44 (29.3%) with mild persistent, 50 (33.3%) with moderate and 22 (14.7%) with severe asthma. None of the included patients suffered from cystic fibrosis, primary ciliary dyskinesia or immunodeficiency. Baseline data for the subjects are presented in Table 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics (n=150).

| Characteristic | Asthma severity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 (n=34) | Grade 2 (n=44) | Grade 3 (n=50) | Grade 4 (n=22) | P | |

| Age (mean±SD, years) | 35.06±13.67 | 32.27±12.20 | 32.50±12.91 | 32.91±13.03 | 0.783 |

| Gender, M:F | 21:13 | 26:18 | 29:21 | 13:9 | 0.989 |

| Body mass index (mean±SD, kg/m2) | 22.19±3.27 | 22.68±3.17 | 22.10±3.00 | 22.65±2.96 | 0.743 |

| Duration of nasal disease (mean±SD, m) | 58.04±46.49 | 72.50±80.43 | 71.17±61.49 | 82.85±88.74 | 0.549 |

| Duration of asthma (mean±SD, m) | 51.03±75.67 | 46.57±62.44 | 50.02±67.47 | 53.59±77.73 | 0.977 |

| Non-smokers: smokers | 29:5 | 38:6 | 42:8 | 21:1 | 0.607 |

| Atopy, no. (%) | 18 (52.9) | 21 (47.7) | 25 (50.0) | 10 (45.5) | 0.948 |

| Baseline FEV1 (% predicted) | 96±11 | 89±13 | 90±16 | 61±18 | 0.000 |

| Daily dose of inhaled fluticasone equivalent (¿g) | NA | NA | 392±142 | 1004±156 | 0.000 |

Abbreviations: M, male; F, female; PEF, peak expiratory flow; NA, not applicable.

Grade 1, mild intermittent; Grade 2, mild persistent; Grade 3, moderate persistent; Grade 4, severe persistent.

All the patients could achieve good control of their asthma in the study period. None of them received short-acting ¿2-agonist, anti-IgE therapy, or oral corticosteroids. The four categories of asthma were similar with respect to the distribution of sex, age, body mass index, duration of nasal disease, or smoking and atopic status. As expected, patients with severe asthma received much higher doses of ICSs and had lower baseline FEV1 (P<0.05).

Onset of asthma and nasal diseaseAmong all the investigated asthmatic patients, 114 (76%) had AR, NAR, CRSwNP or CRSsNP. Among subjects with asthma and nasal disease, 50 (43.9%) had nasal disease first, 30 (26.3%) had asthma first and 34 (29.8%) had both diseases at the same time.

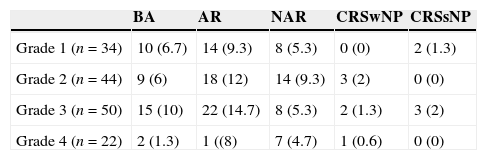

Incidence of AR, NAR, CRSwNP and CRSsNPAccording to the proposed diagnostic algorithm, eventually 66 patients (44%) received a diagnosis of AR; NAR was diagnosed in 37 patients (24.7%); CRS (with/without polyps) was diagnosed in 11 patients (7.3%) and nasal polyps were present in only six of them. The distribution of different kinds of nasal disease in the asthma patients is shown in Table 2. Using Fisher's Exact Test, there was no statistic significance between the severity of asthma and the incidence of AR, NAR, CRSwNP and CRSsNP (P=0.311). The numbers of asthmatic patients who had obvious nasal septal deviation in endoscopic finding with AR, NAR, CRSwNP and CRSsNP were 15 (10%), 9 (6%), 2 (1.3%), and 2 (1.3%), respectively. There was no statistic significance between nasal septal deviation and the incidence of AR, NAR, CRSwNP and CRSsNP (P=0.798, Fisher's Exact Test).

Concomitant AR, NAR, CRSwNP and CRSsNP in asthma patients [no. (%)].

| BA | AR | NAR | CRSwNP | CRSsNP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 (n=34) | 10 (6.7) | 14 (9.3) | 8 (5.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.3) |

| Grade 2 (n=44) | 9 (6) | 18 (12) | 14 (9.3) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Grade 3 (n=50) | 15 (10) | 22 (14.7) | 8 (5.3) | 2 (1.3) | 3 (2) |

| Grade 4 (n=22) | 2 (1.3) | 1 ((8) | 7 (4.7) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) |

Fisher's Exact Test, P=0.311.

Abbreviations: BA, bronchial asthma only; AR, allergic rhinitis; NAR, non-allergic rhinitis; CRSwNP, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps; CRSsNP, chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps.

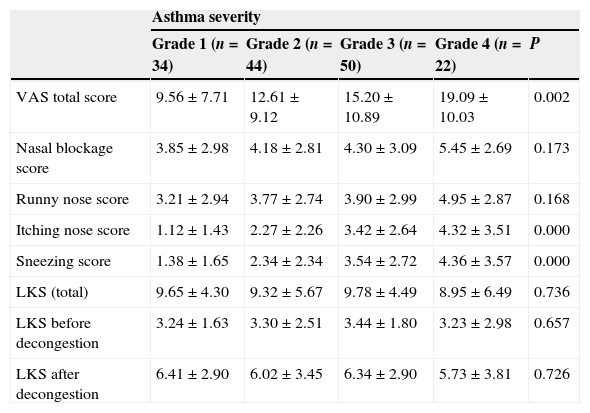

All four groups had high nasal symptoms score (Table 3). There was a significant difference in the total nasal symptoms score among subjects with different grade of asthma (¿2=15.291, P=0.002, Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test). Besides, the total symptom score was significantly higher in patients with severe persistent asthma compared with those with mild intermittent asthma (P=0.002, Bonferroni test). Itching nose and sneezing were significantly more frequent in patients with severe persistent asthma compared with those with mild intermittent asthma (P<0.05). But this was not the case with nasal blockage and runny nose (P>0.05).

Symptom and endoscopic scoring of different categorised asthma (%).

| Asthma severity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 (n=34) | Grade 2 (n=44) | Grade 3 (n=50) | Grade 4 (n=22) | P | |

| VAS total score | 9.56±7.71 | 12.61±9.12 | 15.20±10.89 | 19.09±10.03 | 0.002 |

| Nasal blockage score | 3.85±2.98 | 4.18±2.81 | 4.30±3.09 | 5.45±2.69 | 0.173 |

| Runny nose score | 3.21±2.94 | 3.77±2.74 | 3.90±2.99 | 4.95±2.87 | 0.168 |

| Itching nose score | 1.12±1.43 | 2.27±2.26 | 3.42±2.64 | 4.32±3.51 | 0.000 |

| Sneezing score | 1.38±1.65 | 2.34±2.34 | 3.54±2.72 | 4.36±3.57 | 0.000 |

| LKS (total) | 9.65±4.30 | 9.32±5.67 | 9.78±4.49 | 8.95±6.49 | 0.736 |

| LKS before decongestion | 3.24±1.63 | 3.30±2.51 | 3.44±1.80 | 3.23±2.98 | 0.657 |

| LKS after decongestion | 6.41±2.90 | 6.02±3.45 | 6.34±2.90 | 5.73±3.81 | 0.726 |

Abbreviations: LKS, Lund–Kennedy endoscopic score; VAS, visual analogue scale.

There were no significant differences in the total LKS among subjects with different grades of asthma (¿2=1.273, P=0.736, Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test, Table 2). Neither LKS before congestion nor after decongestion was significantly different among subjects with different grade of asthma (P=0.657 and P=0.726, respectively). Severity of asthma had no effect on nasal endoscopic score. In addition to this, 36 asthmatic patients did not report increased nasal symptoms, but they exhibited increased nasal mucosal swelling when monitored with nasal endoscopy. Their nasal endoscopic score was 6.28±3.08.

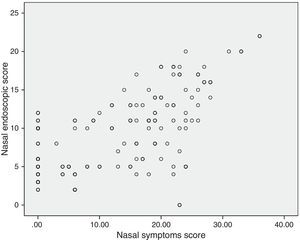

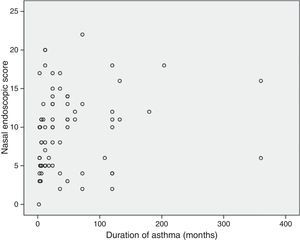

Correlations between resultsThe nasal endoscopic score (total LKS) were significantly correlated at a high degree with the nasal symptoms score (VAS total score) (¿=0.56 and P=0.000, Spearman rank test; Fig. 1). A significant correlation was found between the nasal endoscopic score (total LKS) and the duration of asthma in the patients with different grade of asthma (¿=0.278 and P<0.05, Spearman rank test; Fig. 2).

Parallel relationship does exist between nasal disease and asthma. In a series of studies, Huse et al.11,12 collected asthma and rhinitis severity data in children and found that the presence of severe rhinitis in patients with asthma was associated with worse asthma outcomes. Greisner et al.13 have also reported a parallel course of rhinitis and asthma in 738 individuals who were evaluated on two occasions over a 23-year period. Inversely, there is some evidence that the rhinitis of patients with asthma is worse than that of patients with rhinitis alone. Hellgren et al.14 for example, performed baseline acoustic rhinometry on a large sample of asthmatic patients with rhinitis, rhinitic patients without asthma, and healthy control subjects and found that the asthmatic patients with rhinitis had the lowest cross-sectional area at 4cm and the lowest nasal volume at between 3.3 and 4cm from the nostril. These differences were eliminated with the use of a topical decongestant, showing that they were secondary to differences in vascular congestion and, by consequence, to the activity of nasal disease. All of these confirm that there is a pathogenetic link between asthma and nasal disease.15

In our study, the patients (43.9%) who had nasal disease first were more than the patients (26.3%) had asthma first. Nasal disease was proposed to be a risk factor for asthma. The studies of Plaschke et al.16 and Guerra et al.8 both showed the onset of asthma was associated with allergic and non-allergic rhinitis. Patients with persistent and severe rhinitis had the highest risk for asthma. The authors concluded that rhinitis is a significant risk factor for adult-onset asthma in atopic and non-atopic subjects.

The incidence of AR and NAR observed in our selected population (44% and 24.7%, respectively) was similar to that reported by the retrospective survey conducted by the National Rhinitis Classification Task Force.17 The lower incidence (7.3%) of CRS we have found in our asthmatic patients is in disagreement with the survey by Matsuno et al.,18 in which the result of their questionnaire survey revealed that of all patients with asthma, 36.7% also have sinusitis. Meanwhile, Bresciani et al.19 showed that a high prevalence of sinus disease exists in asthmatic subjects and that a similar prevalence was found in either mild-to-moderate or severe asthmatic patients (30% and 58%, respectively). The above two survey data both came from developed countries, where CRS has been reported to often occur in patients with asthma. However, we suspect that these rates might differ in developing countries, just as we have previously found that Chinese patients with CRS have a low level of asthma comorbidity compared with Western populations.20 This difference might result from distinct immunopathological characteristics of CRS in Chinese patients, specifically from lower levels of eosinophilic inflammation.

The findings of the present study indicate that nasal symptoms are very common in asthmatic patients, and the patients with severe persistent asthma frequently experienced itching nose and sneezing compared to patients with mild asthma. The rate of nasal blockage and runny nose was not significantly greater in patients with moderate and severe asthma. Our findings demonstrated that the severity of asthma was associated with nasal symptoms, consistent with previous reports,1,19 additionally the reason for this is the high frequency of the association between the upper and lower airways. On the other hand, Raherison et al.21 reported that a symptom questionnaire had good sensitivity but poor specificity. Nasal obstruction, runny nose, itching nose and sneezing had good sensitivity for predicting architectural abnormalities, mucosal thickening abnormalities or the presence of secretions.

We observed that 36 asthmatic patients did not report increased nasal symptoms, but they exhibited increased nasal mucosal swelling when monitored with nasal endoscopy. The work of Gaga et al.22 may elucidate it. They have performed nasal mucosal biopsies in patients with asthma who deny any symptoms from upper respiratory tract as well as in patients with asthma and rhinitis. These investigators found that elements of inflammation exist in the nasal mucosa of non-rhinitic asthmatics, some of which do not differentiate them from patients with asthma and rhinitis. At the same time, we must bear in mind that nasal symptoms are not specific to chronic nasal disease, and some patients suffering from sinonasal disease may have normal findings, whereas non-symptomatic patients may have abnormal nose findings.

Our findings did not reveal an association between Lund–Kennedy endoscopic score (LKS) and severity of asthma. There was no significant correlation between the severity of asthma and the incidence of nasal disease. Raherison et al.21 have recently reported that there is no correlation between CT-documented sinonasal involvement and asthma severity, consistent with our findings. Our findings were also coherent with reports by Dixon et al.23 and Williamson et al.,24 in which a disassociation was shown between severity of nasal disease and lung functions in patients with asthma. Also, both upper and lower airways were considered to be related to nasobronchial reflex, postnasal drainage inflammatory mediators, common mucosal susceptibility, and systemic amplification.25 The lack of connection between nasal inflammatory lesion and severity of asthma might suggest that airway tissue remodelling in the nose appears to be far less severe than in the lungs.26 Tissue remodelling in the nose may need a period of time. This also accounts for the significant correlation we discovered between nasal mucosal appearance under endoscope and duration of asthma.

In conclusion, this study points out that nasal endoscopy might play a fruitful role in the management of asthmatic patient, because it can really “see” what the situation of the nose is. We believe that the present result opens new possibilities to monitor nasal mucosal inflammation in asthma, addressing treatment and prevention. The relationship between nasal disease and asthma is complex, and the study we presented hopefully offers a thinking framework for further examination and exploration. In examining and treating this syndrome, we should be simultaneously considering the parallel relationship between rhinitis and asthma and the interactions between the upper and lower airways, which, in turn, might be of a dual nature. In patients with asthma, the nasal airways should become part of standard clinical assessment, and follow-up and rhinosinusitis should be managed aggressively.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.