Double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges (DBPCFC) are the gold standard method for diagnosing food allergies. However, due to the difficulty of their performance on routine clinic, there is a need for laboratory tools in order to minimise the frequency of DBPCFC. Atopy patch test (APT) represents a promising manner of diagnosing delayed-type allergic reactions. The APT may identify patients with food allergies with negative specific IgE. However, the clinical relevance of positive APT reactions is still to be proven by standardised outcome definitions.

The diagnosis of food allergies is based on a response to elimination of the culprit proteins from the diet, followed by a positive reaction to an oral challenge with the suspected food. Many laboratory tests are useful for screening, but their diagnostic value is limited by several issues. No single test is able to identify all patients with food allergies.

To date, double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges (DBPCFCs) remain the gold standard for diagnosing clinically relevant food allergy.1,2 This procedure, however, is time consuming, costly, and bears the risk of life-threatening anaphylactic reactions.3,4 To minimise the frequency of DBPCFCs, attempts have been made to combine laboratory tools to reliably predict the outcomes of oral food challenges.

Several mechanisms are involved in the development of food allergy,5 but only the IgE-mediated reaction, usually associated with an immediate type reaction, is well characterized; the immunological mechanisms associated with a delayed type reaction are still poorly understood.6 A positive skin prick test (SPT) seems to reflect early reactions to food challenges, whereas the atopy patch test (APT) has a high diagnostic efficacy for late phase clinical reactions.7 The APT is aimed at detecting delayed-type allergic reactions, seen in conditions like atopic dermatitis (AD) or digestive disorders,8,9 and could form a relevant and important addition to allergological investigation of patients with both IgE and non-IgE-mediated suspected food allergy and non-IgE-mediated disorders only. It seems that the delayed-type skin reaction in a positive APT is allergen-specific and correlates with the presence of food allergy.

First descriptions of APT date from 1982,10 as “skin reactions induced in patients with atopic dermatitis by applying food allergens or aeroallergens on non-lesional skin”. Although APTs had shown efficacy in patients with atopic dermatitis in the diagnosis of inhalants-associated allergy,11,12 their effectiveness for diagnosing food hypersensitivity was only later investigated,13,14 and demonstrated some evidence that a positive response to the APT was associated with a delayed-type reaction to foods; when used in parallel with a SPT, it increased the detection rate.

The APT may identify those patients with food allergies with negative SPT and/or specific serum IgE. However, the clinical relevance of positive APT reactions is still to be proven by standardised provocation and avoidance tests and may also depend on the APT model used as well as the outcome definitions.

Several technical procedures, aimed at increasing the permeability of the tested skin (including abrasion, stripping and high concentrations of allergens vehiculated in special solvents), were initially widely used to facilitate positive test results.15–17 All of these procedures were later abandoned, because they proved to be unnecessary and difficult to standardise.

APT is now a widely applied procedure, especially aimed at the diagnosis of food allergy.18–22 Some points, however, remain unresolved. In general, in healthy or symptomatic subjects, APT results differ widely among tested allergens (naive or standardised food) and depend closely on technical variables (e.g. allergen concentration, size of the chamber, occlusion time and site of allergen application)16,17,23,24 and on personal characteristics of the tested person, e.g. age.23–28

Kalach et al.29 compared a ready-to-use APT, the Diallertest, with another APT device, the Finn Chamber, which was the most commonly used device, in paediatric cow's milk allergic patients. All children underwent both APT techniques, with a reading 72h after application, followed by a milk elimination diet for 4 to 6 weeks and open cow's milk challenge. Diallertest exhibited a significantly higher sensitivity (76% vs 44%) and test accuracy (82.9% vs 63.4%) than the comparator, whereas both techniques exhibited high specificity and positive predictive value and were devoid of any side effects.

The ready-to-use cow's milk protein APT (Diallertest) is 26mm in diameter, with a central transparent plastic membrane (11mm in diameter) of polyethylene charged with electrostatic forces able to retain powdered cow's milk for a long period and to allow a visual monitoring of cutaneous reactions.29

Finn chamber (Hermal, Reinbek, Germany) can also be used for different allergens (cow's milk, hen's egg, wheat and soy).18 Fresh foods are distributed on filter paper and covered with 6, 8 or 12mm Finn chambers for 48h. The diagnostic accuracy of the APT using a 12mm Finn chamber was greater than for the 6mm chamber.27

Following the official consensus published by the Section on Dermatology and the Section on Pediatrics of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) and GA2 LEN, 2006,30 some rules could be pointed out:

- •

APT with foods is not standardised yet, but fresh foods should be preferred over commercial extracts.

- •

Apparently there is no difference between the vehicles used (petrolatum, aqueous solution in PBS).

- •

Reactions are more frequently positive on the back in comparison with the arms.

- •

Most of the studies have used the aluminium chamber (Finn Chamber, Epitest Ltd Oy).

- •

Glucocorticosteroids and topical immunomodulators can reduce the macroscopic outcome of the APT reaction. APT should be performed on skin with no previous local treatment.

- •

No information is available concerning treatment with oral antihistamines, but it is considered safer that antihistamines be withdrawn at least 72h prior to the APT.

- •

The influence of age in terms of sensitivity is controversial. Some authors found no significant difference, while some showed that frequency of positive APT results was lower in children >2 years compared with younger children.

- •

Better results were obtained after occlusion time of 48h and reading at 48 and 72h.

- •

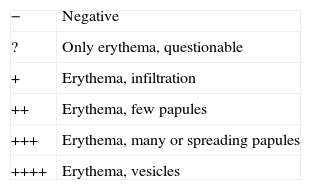

APT reading is suggested as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.Revised European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis (ETFAD) key for atopy patch test (APT) reading

− Negative ? Only erythema, questionable + Erythema, infiltration ++ Erythema, few papules +++ Erythema, many or spreading papules ++++ Erythema, vesicles Adapted from Turjanmaa K et al.30

- •

Side effects are not common and, when present, they are mostly mild, including local flares, contact urticaria, irritation from adhesive tapes and local itching.

There is not sufficient evidence to support the current addition of the APT to the standardised allergological evaluation in patients presenting with AD or GI symptoms with suspected food allergy. The optimum allergen concentrations, vehicles for different allergens, optimum sizes of Finn chambers for different allergens and other materials for occlusion than Finn chambers are some issues that need to be clarified. The preferred way of evaluating these and other aspects of standardisation is to perform prospective, multicentre studies in clinics with adequate experience of patch testing and challenge/allergen avoidance procedures.

On the other hand, all the studies are worthwhile to undertake because a positive APT with food allergens seems promising for further use as a diagnostic test for allergen-specific delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction

Disclosure of potential conflict of interestNo conflict of interest.