In this study, we aimed to investigate the relationship between pertussis infections and allergic diseases in two cross-sectional questionnaire-based surveys carried out in 1997 and 2004. We also measured serum level of antibody to B. pertussis.

Material and MethodsTwo cross-sectional, questionnaire-based surveys were carried out in 1997 (n=3164) and 2004 (n=3728). 361 cases and 465 controls were recruited from both surveys. The skin tests were performed using standardised extracts. The level of pertussis specific IgG was measured in 136 allergic and 168 non-allergic children.

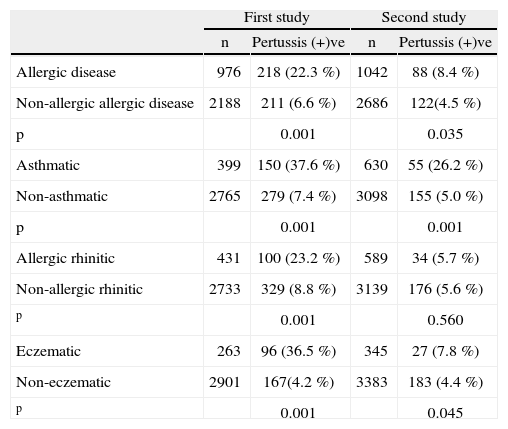

ResultsWe found that allergic diseases prevalence was significantly higher in the children suffering from pertussis infections (22.3 % first and 8.8 % second survey) compared to children who did not suffer from pertussis infections (6.6 % first and 4.5 % second survey) (p=0.001 and p=0.035, respectively). Asthma prevalence was also significantly higher in children suffering from pertussis infection (37.6 % first and 26.2 % second survey) compared to children who did not suffer from pertussis (7.4 % first and 5.0 % second survey) (p=0.001 and p=0.001, respectively). However, the mean serum levels of anti-pertussis IgG were similar in allergic and non-allergic groups (p>0.05).

ConclusionAlthough pertussis antibody levels in atopic and non-atopic children were similar to each other, pertussis infection still seemed to have a significant effect on the development of atopic diseases.

The incidence and prevalence of asthma and allergic diseases have signiflcantly increased in many countries in recent decades1,2. Although the reasons for such a rise are not exactly known, the hygiene hypothesis has gained strong support over the past years3. Exposure to microbial products in early life could be an underlying factor for this hypothesis, but the mechanisms underlying these protective effects are not exactly known. The reduced microbial stimulation in early life may prevent maturation of Th1 immunity leading to an allergen-specific Th2 immune response following natural exposure to allergens4–6. Several studies suggested that there was an inverse association between the incidence of allergic diseases and infections. It has been suggested that a powerful Th1 inducing infection, during or prior to allergic sensitisation, should decrease or protect against the development of allergic diseases7,8.

Bordetella pertussis is a gram-negative bacterium which causes pertussis or whooping cough. It has previously been reported that B. pertussis infection stimulates Th1 type immune responses9. Recovery from infection is associated with the development of B. pertussis-specific Th1 cells in humans and mice10. Evidence for an association between pertussis and atopy is conflicting. In children with pertussis infection, IgE to pertussis toxin and common allergens, as well as increased total serum IgE levels, can be detected11. However, a study indicated that pertussis in childhood did not predispose to subsequent asthma12. The possible influence of B. pertussis vaccine on the development of allergy has been widely investigated. While previous reports postulated that pertussis vaccine constitutes a risk for the development of allergic diseases13,14, to the best of our knowledge this could not yet be confirmed by further recent studies15,16.

In the present study, we investigated the relationship between physician-diagnosed pertussis, and compared the results of two cross-sectional data from ISAAC written questionnaire-surveys conducted in 1997 and 2004. We also examined whether serum antibody levels to B. pertussis were different in cases of both surveys. Since prevalence of asthma and allergic diseases were previously dealt with in other studies, our main focus with this study was primarily on prevalence of pertussis infections.

Material and MethodsTwo cross-sectional, questionnaire-based surveys were carried out in 1997 (n = 3164) and 2004 (n = 3728) in Adana, Turkey17,18. The questionnaire, identical in both surveys, was completed by parents of children younger than 12 years old, and by the students themselves if older than 12. Both surveys were conducted over the same months of March-June. The cluster sampling method was similar in both surveys. Standard ISAAC core questions for wheezing, asthma, rhinitis and eczema were used. The questionnaire also included questions on age, gender, socioeconomic status, type of residence, environmental factors such as dampness in the house, smoking exposure, and current pet ownership. The following questions were also added to the questionnaire to identify whooping cough: “Have you/has your child ever had whooping cough?” “Have you/has your child ever had been diagnosed whooping cough by doctor?”

Asthma was defined as the occurrence of wheezing and/or a doctor's diagnosis of asthma and/or use of asthma medication. Allergic rhinitis was defined as the presence of a runny or blocked nose without having a cold or flu, accompanied by itchy-watery eyes and/or some interference of this nose problem with daily activities. Eczema was defined as itchy skin rash that has been recurring for at least 6 months and affecting particular skin sites (i.e. folds of the elbows, behind the knees, in front of the ankles, under the buttocks, or around the neck, ears, or eyes).

Based on these criteria 361 cases with a mean age of 10.3 ± 1.4 years (155 male, 206 female) and 465 controls with a mean age of 10.9 ± 1.3 years (210 male, 255 female) were recruited from a random list of both surveys. These cases and controls again attended the study centre for a detailed questionnaire, skin prick test, and blood sampling. Blood samples were allowed to clot at room temperature for one hour, then cooled in a refrigerator for 1–2 hours before being centrifuged. Sera were stored at —80 °C until the seralogic analysis was carried out.

The skin tests were performed by the same investigator using standardised extracts of Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Dermatophagoides farinea, grasses, cereals, tree I and II mixes, olive, moulds, cat, dog, cockroach, hen's egg, cow's milk, and cacao (Allergopharma, Germany). Histamine dihydrochloride (10 mg/mL) and glycerol diluent were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. A wheal size greater than 3 mm was used as a positive result. Patients with at least one positivity in skin prick tests were considered atopic.

The level of pertussis specific IgG was measured in 136 allergic (56 male, 80 female; mean age 10.1 ± 0.8 years) and 168 non-allergic children (72 male, 96 female; mean age 10.0 ± 0.6 years). Of the children who took part in the survey in 1997, 89 were allergic, and 106 were non-allergic. In the survey of 2004, 47 were allergic and 62 were non-allergic. Of allergic children, 95 had asthma, 74 had rhinitis, and 15 eczema. All children had received a whole cell pertussis vaccine combined with diphtheria and tetanus toxoid at 2, 4 and 6 months of age, and a booster dose at 18 months of age.

Pertussis antibody was determined by an enzyme linked-immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using a commercial kit (DRG Diagnostic, Germany) which detects antibodies against pertussis toxin and other pertussis antigens. The kit was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. The optical density (OD) was recorded with a 450 nm length wave reader (Medispec Esr-200). Results were measured as OD and expressed as arbitrary unit (U.) according to the instructions. Samples were considered positive if the absorbance was 10 % above the cut-off value.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethic Committee of University of Cukurova. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of all the participating children.

The statistical analyses were made using SPSS-X version 11.0 for Windows and Epi-info6.0. Antibody levels were expressed as median and interquartiles. As data was not normally distributed, the Man-Whitney U-test was used to compare the differences between groups. The Fisher exact test was applied when assessing the differences in positive and negative pertussis children.

ResultsA total of 429 (13.6 %) in the first, and 210 (6.3 %) in the second survey had suffered from B. pertussis infection. We found that pertussis infections had significant effect on the prevalence of atopic diseases such as asthma and allergic rhinitis in both surveys. In these two surveys, allergic diseases prevalence was significantly higher in the children suffering from pertussis infections (22.3 % first and 8.8 % second survey) compared to children who did not suffer from pertussis infections (6.6 % first and 4.5 % second survey) (p = 0.001 and p = 0.035, respectively). Asthma prevalence was also significantly higher in children suffering from pertussis infection (37.6 % first and 26.2 % second survey) compared to children who did not suffer from pertussis (7.4 % first and 5.0 % second survey) (p = 0.001 and p = 0.001, respectively. A similar pattern was also observed for eczema; yet pertussis seemed to have a significant effect on allergic rhinitis in the first and not in second survey (p = 0.001 and p > 0.05) (Table I). Additionally, the history of pertussis infection was found statistically different between children with skin prick test positive and negative which was 22.5 % and 14 %, respectively (p = 0.017).

Allergic disease development in children according to pertussis history

| First study | Second study | |||

| n | Pertussis (+)ve | n | Pertussis (+)ve | |

| Allergic disease | 976 | 218 (22.3 %) | 1042 | 88 (8.4 %) |

| Non-allergic allergic disease | 2188 | 211 (6.6 %) | 2686 | 122(4.5 %) |

| p | 0.001 | 0.035 | ||

| Asthmatic | 399 | 150 (37.6 %) | 630 | 55 (26.2 %) |

| Non-asthmatic | 2765 | 279 (7.4 %) | 3098 | 155 (5.0 %) |

| p | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Allergic rhinitic | 431 | 100 (23.2 %) | 589 | 34 (5.7 %) |

| Non-allergic rhinitic | 2733 | 329 (8.8 %) | 3139 | 176 (5.6 %) |

| p | 0.001 | 0.560 | ||

| Eczematic | 263 | 96 (36.5 %) | 345 | 27 (7.8 %) |

| Non-eczematic | 2901 | 167(4.2 %) | 3383 | 183 (4.4 %) |

| p | 0.001 | 0.045 | ||

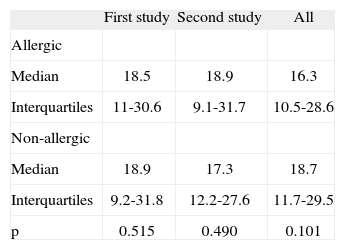

On the whole the mean serum levels of anti-pertussis IgG were similar in allergic and non-allergic groups (Table II). The concentration of IgG antibodies to B. pertussis ranged between 1 to 125 U/ml in the whole population of children. When both surveys were separately examined, all children in the first, as well as in the second survey, had similar levels of anti-pertussis IgG. According to the cut-off point established by the study, 104/136 (75.4 %) allergic children and 131/168 (77.9 %) non-atopic children were positive for IgG antibody to B. pertussis (p > 0.05). The rate of children with very high IgG antibody level (> 100 U/ml) was 12/136 (8.8 %) in the atopic group and 13/168 (%7.7) in the non-atopic group (p > 0.05).

DiscussionB. pertussis is a gram negative bacterium and causative agent of pertussis or whooping cough; it is a respiratory disease that remains as a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in infants worldwide. In this study, we found that although natural infection with B. pertussis might be associated with increased incidence of allergic asthma, rhinitis, and eczema, the serum levels of anti-pertussis IgG were found to be similar in allergic and non-allergic groups. Since the data on the levels of IgG against B. pertussis in allergic children is rather limited, the discrepancy is rather hard to explain here. However, the measured IgG levels may not be reflecting the actual situation prior to the development of allergic diseases in children. Thus, the measured IgG levels may be associated with vaccination or natural exposure to B. pertussis following sensitisation. Our results were in line with a study conducted by Blanco-Quiros A et al.19. In another study by Holt PG et al.20, it was found that although the mean value of anti-B.pertussis IgG was lower in the atopic compared to the non-atopic children, the difference, however, was found to be statistically insignificant.

The seroprevalence of pertussis antibodies found in our study population was 75.6 %. This level is consistent with high seroprevalence rates in children and adults in Turkey and other countries21–25. Someone with very high IgG antibodies (> 100.), or with a positive IgA, may have suffered a recent pertussis infection25. In our study we did not investígate IgA against B. pertussis. The rate of children with very high IgG antibody level was similar in both atopic and non-atopic groups. Evidence for the possible effects of B. pertussis on subsequent development of asthma and atopy remains a matter of controversy.

In a population-based study, Wjst M and et.25 compared the prevalence of allergic sensitisation and allergic rhinitis in children with and without previous pertussis infection. They found that infection with pertussis seemed to have a weak influence on allergic sensitisation. A prospective study conducted on 25 children evaluated whether pertussis induced the development of allergy11. The patients underwent allergy diagnostics during pertussis infection, and at a follow-up visit 8–14 months later, the researchers indicated that pertussis may have induced IgE production in children. Sundqwist M et al.12 showed that pertussis in infancy did not predispose to subsequent asthma development.

Pertussis toxin has been used as an adjuvant to enhance IgE formation against simultaneously administered antigen in animal model27. Infection with B. pertussis modulates allergen priming and severity of airway pathology in a murin model allergic asthma and clinical studies, showing that B. pertussis infection exacerbated allergic asthmatic responses28. However, Kim YS et al.29 reported that systemic administration of whole-cell B. pertussis strongly inhibited allergic airway reactions such as eosinophil recruitment into the airway, lung inflammation, and airway hyperresponsiveness to methacholine.

Although some studies have suggested that immunisation might increase the risk for atopic diseases30, some others reported a protective effect for immunisation and natural infection against atopy28,31. Ennis DP et al.32 studied whether whole cell pertussis vaccine enhanced or prevented B. pertussis induced exacerbation of allergic asthma. They found that whole cell pertussis vaccine had protective effect on asthma. The same researchers sensitised rats with 10 μgHDM intrathecally or intra peritoanelly that whole killed pertussis organisms were given with or without simultaneous injections of whole killed B. pertussis organisms. Ten days later, all rats were challenged with 5 μgHDM via the trachea. The researchers found that simultaneous exposure to Th2 inducing vaccine component and allergic protein may have been a risk factor for allergic sensitisation and development of asthma in susceptible individuals.

In conclusion, we can suggest that despite the fact we found pertussis antibody levels in atopic and non-atopic children to be similar to each other, pertussis infection still seemed to have a signiflcant effect on the development of atopic diseases.