The GINA guidelines (GL)1, the BTS-SIGN GL2, and the paediatric PRACTALL GL3, indicate inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) as the first choice for controller therapy of paediatric asthma. The authors of BTS-SIGN GL recommended a leukotriene receptor antagonist, if ICS cannot be administered. Montelukast (MLK) is the most commonly used in children. If ICS remain the first choice, they can be considered the Gold Standard for pharmacological asthma prevention and the value of any alternative treatment must be measured against them, not only against a placebo. Here we will try to shed some light as to which of those two drugs is better according to the present evidence.

We chose a generic research strategy trying to analyse all relevant articles. We searched MEDLINE to gather relevant, English-language articles using search terms “montelukast AND asthma”, selecting “randomized controlled trial” and “all child”. No time limits were imposed. The bibliography of the relevant articles was checked. We considered eligible for the inclusion randomised, double-blind, double-dummy studies with paediatric data, where 80 % or more of randomised patients are included in the final analysis of the data, and with a Jadad score4 of ≥ 3. The search ended on December 16, 2008.

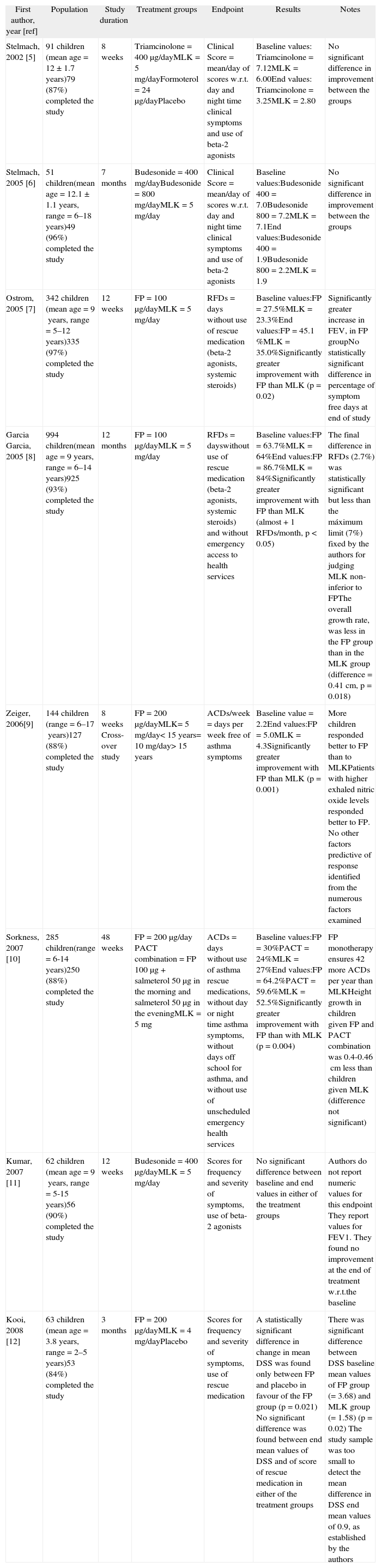

What is the evidence?One hundred and fifty seven papers were examined. Eight studies5–12 met the inclusion criteria of the review. Table I summarises the studies, highlighting relevant clinical results. Data were not aggregated, for the diversity of the endpoints and of the clinical scores.

Summary of studies found up to December 15, 2008

| First author, year [ref] | Population | Study duration | Treatment groups | Endpoint | Results | Notes |

| Stelmach, 2002 [5] | 91 children (mean age = 12 ± 1.7years)79 (87%) completed the study | 8weeks | Triamcinolone = 400μg/dayMLK = 5mg/dayFormoterol = 24μg/dayPlacebo | Clinical Score = mean/day of scores w.r.t. day and night time clinical symptoms and use of beta-2 agonists | Baseline values: Triamcinolone = 7.12MLK = 6.00End values: Triamcinolone = 3.25MLK = 2.80 | No significant difference in improvement between the groups |

| Stelmach, 2005 [6] | 51 children(mean age = 12.1 ±1.1years, range = 6–18years)49 (96%) completed the study | 7months | Budesonide = 400mg/dayBudesonide = 800mg/dayMLK = 5mg/day | Clinical Score = mean/day of scores w.r.t. day and night time clinical symptoms and use of beta-2 agonists | Baseline values:Budesonide 400 = 7.0Budesonide 800 = 7.2MLK = 7.1End values:Budesonide 400 = 1.9Budesonide 800 = 2.2MLK = 1.9 | No significant difference in improvement between the groups |

| Ostrom, 2005 [7] | 342 children (mean age = 9years, range = 5–12years)335 (97%) completed the study | 12weeks | FP = 100μg/dayMLK = 5mg/day | RFDs = days without use of rescue medication (beta-2 agonists, systemic steroids) | Baseline values:FP = 27.5%MLK = 23.3%End values:FP = 45.1 %MLK = 35.0%Significantly greater improvement with FP than MLK (p = 0.02) | Significantly greater increase in FEV, in FP groupNo statistically significant difference in percentage of symptom free days at end of study |

| Garcia Garcia, 2005 [8] | 994 children(mean age = 9years, range = 6–14years)925 (93%) completed the study | 12months | FP = 100μg/dayMLK = 5mg/day | RFDs = dayswithout use of rescue medication (beta-2 agonists, systemic steroids) and without emergency access to health services | Baseline values:FP = 63.7%MLK = 64%End values:FP = 86.7%MLK = 84%Significantly greater improvement with FP than MLK (almost +1 RFDs/month, p < 0.05) | The final difference in RFDs (2.7%) was statistically significant but less than the máximum limit (7%) fixed by the authors for judging MLK non-inferior to FPThe overall growth rate, was less in the FP group than in the MLK group (difference = 0.41cm, p = 0.018) |

| Zeiger, 2006[9] | 144 children (range = 6–17years)127 (88%) completed the study | 8weeks Cross-over study | FP = 200μg/dayMLK= 5mg/day< 15years= 10mg/day> 15years | ACDs/week = days per week free of asthma symptoms | Baseline value = 2.2End values:FP = 5.0MLK = 4.3Significantly greater improvement with FP than MLK (p = 0.001) | More children responded better to FP than to MLKPatients with higher exhaled nitric oxide levels responded better to FP. No other factors predictive of response identified from the numerous factors examined |

| Sorkness, 2007 [10] | 285 children(range = 6-14years)250 (88%) completed the study | 48weeks | FP = 200μg/day PACT combination = FP 100μg + salmeterol 50μg in the morning and salmeterol 50μg in the eveningMLK = 5mg | ACDs = days without use of asthma rescue medications, without day or night time asthma symptoms, without days off school for asthma, and without use of unscheduled emergency health services | Baseline values:FP = 30%PACT = 24%MLK = 27%End values:FP = 64.2%PACT = 59.6%MLK = 52.5%Significantly greater improvement with FP than with MLK (p = 0.004) | FP monotherapy ensures 42 more ACDs per year than MLKHeight growth in children given FP and PACT combination was 0.4-0.46cm less than children given MLK (difference not significant) |

| Kumar, 2007 [11] | 62 children (mean age = 9years, range = 5-15years)56 (90%) completed the study | 12weeks | Budesonide = 400μg/dayMLK = 5mg/day | Scores for frequency and severity of symptoms, use of beta-2 agonists | No significant difference between baseline and end values in either of the treatment groups | Authors do not report numeric values for this endpoint They report values for FEV1. They found no improvement at the end of treatment w.r.t.the baseline |

| Kooi, 2008 [12] | 63 children (mean age = 3.8years, range = 2–5years)53 (84%) completed the study | 3months | FP = 200μg/dayMLK = 4mg/dayPlacebo | Scores for frequency and severity of symptoms, use of rescue medication | A statistically significant difference in change in mean DSS was found only between FP and placebo in favour of the FP group (p = 0.021) No significant difference was found between end mean values of DSS and of score of rescue medication in either of the treatment groups | There was significant difference between DSS baseline mean values of FP group (= 3.68) and MLK group (=1.58) (p = 0.02) The study sample was too small to detect the mean difference in DSS end mean values of 0.9, as established by the authors |

FP: Fluticasone proprionate; MLK: Montelukast; ref: bibliography reference; NS: not significant; RFDs: rescue-free days; ACDs: asthma control days; DSS: daily symptom score.

In seven studies the authors found that the active treatment induced a greater improvement in asthma symptoms over the baseline one. In two of them (142 children), both by Stelmach et al.5,6, the authors found no statistically significant difference between ICS and MLK. In the other five (1,828 children) the authors found a statistically significant difference in favour of the ICS group. In the study with the highest number of participants (994 children) by Garcia Garcia et al.8 (MOSAIC study) the authors concluded that MLK is not inferior to fluticasone propionate (FP). They had established that the two treatments would be considered equivalent if the upper limit of the 95 % confidence interval for the difference in the primary endpoint (mean percentages of asthma rescue-free days [RFDs]) was above —7 % (Table I). In the MOSAIC study, the least-squares mean difference was —2.7 %, a difference of < 1 RFD/month, with the 95 % Confidence Interval within the noninferiority limit of —7 %. However, the 2.7 % difference is statistically significant, with a p < 0.05, and we have to attribute this difference to the treatment. That was the reason for the Garcia Garcia study8 to be placed in our review among those reporting a greater improvement with ICS use.

The study of Kooi et al.12 is the first, and to date the only, RCT about this topic which included preschool children (2–5years). The study sample was too small, so statistical β-error cannot be excluded. During the study period daily symptom score (DSS) improved in all three groups, but the authors found a statistically significant difference only between FP and placebo in favour of the former (Table I). This result could be influenced by the higher DSS baseline mean values of the FP group (3.68) vs MLK group (1.58) (p = 0.02). No differences in DSS final values and in the score of rescue medication use between groups were found.

How much improvement in using ICS vs MLK?Garcia Garcia et al.8 are not mistaken when they state that a significant difference in favour of one treatment over another is only one of the elements to be considered when making a clinical decision. When statistical significance was verified, we had to consider what the clinical relevance of the results obtained is. It is very difficult to quantify the clinical relevance because many factors may influence it, such as patients’ differing needs, adverse effects, and costs. The choice made by Garcia Garcia et al. was supported by Szefler et al.13 (study not included here due to the high number of dropouts: 29 %). The authors13 postulated a difference of at least 10 % (Minimum Clinically Relevant Difference) between budesonide and MLK to calculate the necessary sample size. These authors would have considered the two treatments to be equivalent, had the difference between them been less than 10 %, a percentage higher than the 7 % chosen by Garcia Garcia et al.8.

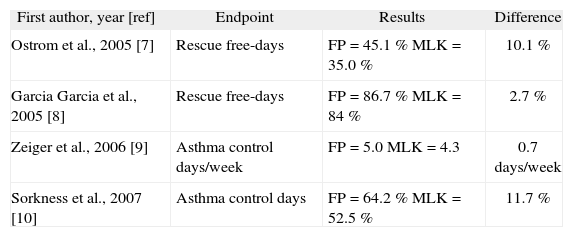

Table II provides a short summary of the extent of the improvement offered by ICS vs MLK in the four studies reporting this result. The extra improvement offered by ICS (FP in all cases) was around 10 %-12 % with the exception of the MOSAIC study8. A similar result at least concerning asthma control days (ACDs) — was obtained in a study conducted predominantly on adults by the American Lung Association Asthma Clinical Research Centers14.

Trial-end values for the primary endpoint in the four studies reporting a greater benefit with ICS than MLK

| First author, year [ref] | Endpoint | Results | Difference |

| Ostrom et al., 2005 [7] | Rescue free-days | FP = 45.1 % MLK = 35.0 % | 10.1 % |

| Garcia Garcia et al., 2005 [8] | Rescue free-days | FP = 86.7 % MLK = 84 % | 2.7 % |

| Zeiger et al., 2006 [9] | Asthma control days/week | FP = 5.0 MLK = 4.3 | 0.7days/week |

| Sorkness et al., 2007 [10] | Asthma control days | FP = 64.2 % MLK = 52.5 % | 11.7 % |

Was an improvement of 10 %-12 % in RFDs (or ACDs) so significant as to make ICS irreplaceable, whatever the circumstances? We cannot forget that Stelmach et al.5,6, Garcia Garcia et al.8, and Kooi et al.12 found either no difference or a far smaller difference between ICS and MLK.

We have to consider that ICS therapy is associated with a reduced growth in height of 0.4cm per year, as revealed by long-term studies8,10 and as recently demonstrated in a short-term study15. We could also consider other aspects, such as relative costs and patients’ compliance with oral and inhaled treatments, often to be taken more than once a day. A detailed analysis and evaluation of these and other factors is clearly beyond the objective of this review.

Another factor in this evaluation could be conflict of interest:

- –

- –

Ostrom et al.7 were sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline Inc, and some of the authors are employees of that company

- –

Garcia Garcia et al.8 were sponsored by Merck & Co, and some of the authors are employees of that company

- –

Zeiger et al.9 and Sorkness et al.10 were sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. In any case, all authors received financial support from various asthma drug manufacturers

- –

Kooi et al.12 state that they do not have any special financial interest concerning their work, and the study was financially supported by an unrestricted grant from Merck Sharp and Dohme.

However, we cannot quantify the effect of a conflict of interest on the results of the studies reported.

ConclusionsOur personal experience and analysis of the medical literature shows that ICS are the first choice in paediatric persistent asthma, this is what we prefer to use in clinical practice and is what paediatric guidelines on asthma indicate. We know that in the treatment of preschool children with persistent asthma, ICS effectiveness vs placebo has little clinical relevance, but this is the best possible choice for the moment. In our opinion, prophylactic therapy has a minor role in intermittent wheezing or asthma, pharmacological treatments are associated with modest clinical relevance, so we do not prescribe any controller therapy for these patients.

The examination of the best scientific evidence currently available, supports the indication of MLK monotherapy as an alternative treatment for the prevention of mild persistent paediatric asthma. MLK is a valid choice for children who have been found unable to use ICS, i.e. children in poor environments, not compliant with inhalation system and/or victims of adverse effects. In the last case if a child shows a drop in growth rate in the absence of other possible causes, the step down of ICS and overlap with MLK for two weeks, followed by MLK monotherapy, could be recommended to permit recovery, as previously demonstrated16. The wisdom of this choice regarding asthma control and normalisation of growth rate must be carefully assessed on an individual basis.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.