Risk factors for wheezing specifically during the first year of life have been studied in well-developed countries, but the information from developing countries is very scarce. There are no such studies focusing on factors derived from poverty. The aim of the present study was to determine if risk factors related to poverty are associated to wheezing during the first year of life in infants from Honduras and El Salvador.

MethodsA survey, using a validated questionnaire, was carried out in the metropolitan area of San Pedro Sula (Honduras) and in La Libertad (El Salvador) in centres where infants attended for a scheduled vaccination shot or a healthy child visit at 12 months of age. Fieldworkers offered questionnaires to parents and helped the illiterate when necessary. The main outcome variable was wheezing during the first year of life, as reported by parents.

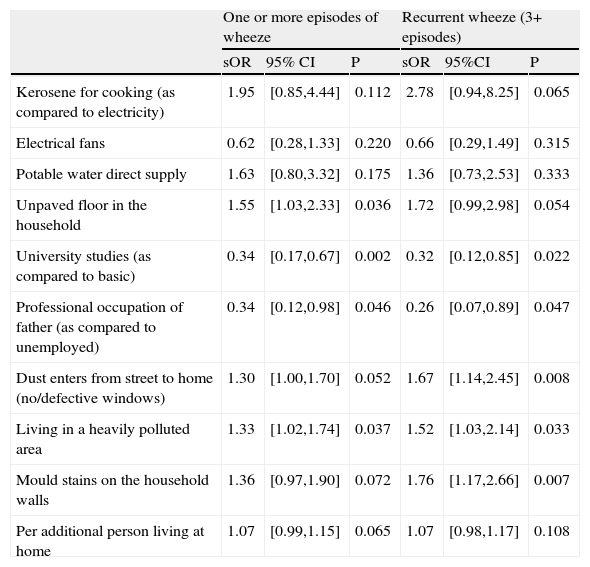

ResultsA total of 1047 infants in El Salvador and 780 in Honduras were included in the analysis. The prevalence of wheeze in the first year was higher in El Salvador (41.2%) than in Honduras (27.7%), as was recurrent wheezing defined as three or more episodes (18.4% vs. 11.7%). Wheezing and recurrent wheezing was associated to unpaved floor in the household (summary odds ratios for both countries 1.55, p=0.036 and 1.72, p=0.054 for any wheeze and recurrent wheezing, respectively); dust entering from streets (1.30, p=0.052 and 1.67, p=0.008); living in a heavily polluted area (1.33, p=0.037 and 1.52, p=0.033); and having mould stains on the household walls (1.36, p=0.072 and 1.76, p=0.007). Furthermore, marginal associations were found for additional person at home and use of kerosene as cooking fuel. University studies in the mother (0.34, p=0.046 and 0.32, p=0.022) and a professional occupation in the father (0.34, p=0.046 and 0.26, p=0.047) were associated to a lower risk.

ConclusionsThe prevalence of wheezing and recurrent wheezing is notoriously high in El Salvador and Honduras. In those populations factors related to poverty are associated to a higher prevalence of wheezing and recurrent wheezing, whereas higher maternal education and paternal professional occupation behave as protective factors.

Although risk factors for wheezing during infancy and preschool age have been extensively studied in developed countries, there is much less information about those risk factors when wheezing is restricted just to the first year of life. Furthermore, the information from low-resourced countries is almost inexistent.1

One of the earliest results on those risk factors during the first year of life was reported by Bisgaard et al.2 who found that poor social environment, a smoking mother, day-care attendance, male gender, being born in April through September (in Denmark) and preterm birth were all independent risk factors for wheezing. Day-care attendance has been pointed out as a very important risk factor in subsequent studies.3–5 Parental history of asthma -sometimes only maternal 6 if wheeze persistency was considered- has also been found to be associated to early infant wheezing in several studies, which have focused their attention on the first year of life6,7. Parental smoking has also been consistently associated to wheezing during the first year of life 5,6, and smoking during pregnancy seems to be a risk factor independently of the mother smoking after delivery.8–10 In fact, smoking in pregnancy is related to a poor lung function in the infant at one month of age.11

The prevalence of first year wheeze decreased to half after a heavily pollutant factory was closed in Calarasi (Romania).12 Dampness at home has also been found to be a risk factor for early wheeze 13 independently of house dust mites growing. Recently, antibiotics consumption by the mother during pregnancy 14, rotavirus infection during the first year 15, and Chlamydia pneumoniae infection at 4 years 16 have also been significantly associated to wheezing during the first months of life. Furthermore, high mass index in the newborn is associated with reduced neonatal lung function11.

The aforementioned studies have been carried out in affluent countries. However, two of them have pointed out that poor economic conditions and young maternal age (which is more frequent in non-affluent countries) may be risk factors for early wheezing.2,6 Thus, we were interested in studying situations derived from poverty, which can be found more easily in non-affluent countries, and how they could be associated to the prevalence of wheeze. Therefore, we conducted a survey in a population-based cohort of one-year-old infants in San Pedro Sula (Honduras) and La Libertad (El Salvador), which are both non-affluent countries with similar genetic and environmental backgrounds.

MethodsThe “Estudio Internacional de Sibilancias en Lactantes (EISL)” (International Study of Wheezing in Infants) is a multicentre, cross-sectional, international, population-based study which is carried out using standardised methods and a validated questionnaire 17–19 partially based on that of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) (http://www.isaac.auckland.ac.nz). It includes questions on wheezing during the first year of life and also on risk/protective factors.

According to the World Bank 2007 statistics, both Honduras and El Salvador are in the lower-middle per capita income group (US$2859 for El Salvador and US$1560 for Honduras). Both countries, situated in Central America and sharing a common border, have tropical climate and very comparable traditions.

Subjects and sampling frameAll the primary care health clinics where infants attend for growth/development monitoring and/or vaccine administration, according to the national public health programmes in each country, and located in the health area corresponding to the “San Rafael” hospital (La Libertad, EL Salvador) or to the “Centro de Neumología y Alergia” (San Pedro Sula, Honduras), were included for infant recruiting. Health clinics were randomly chosen until the number of infants included was around 1000. Parents or guardians were invited to complete the questionnaire when infants were brought for a scheduled vaccine administration or a preventive health care visit around the age of one year, emphasizing that questions were related to events which occurred during the first 12 months of life of their children. Parents were offered help to answer questionnaires by fieldworkers: medical students (El Salvador) or nurses (Honduras). The fieldwork was carried out between April 2008 and November 2008.

In order to significantly detect a difference in the prevalence of recurrent wheezing (3 or more episodes in the first year of life) of 5% between two centres, one of them having around 20%, with a confidence level of 95% and a power of 80%, samples of at least 1000 infants were required from participating centres.

DefinitionsWheezing was defined as a positive answer to the question: “Has your child had wheezing or whistling in the chest during the first 12 months of his/her life?” which was previously validated in the languages of the study.17–19 Severe wheeze was defined as an affirmative response from the parents to the question “During the first 12 months of your child’s life, was wheezing or whistling in the chest so important that you felt he/she had difficulties to breathe and was suffocating?”

The factors analysed in the present study are those related to poverty which were included in the questionnaire, such as: air conditioning, electrical fans, direct connection to potable water, in-house complete toilet, paved floor in the house, in-house kitchen, telephone (mobile or land line), dust entering easily from the street to the house (as a measure of street paving and window quality), heavy air pollution from industries or traffic (as reported by parents), mould stains on the household walls, complete vaccination schedule according to the Health Ministry in each country (all items answered as yes or no). Additionally, the questionnaire included topics with several possible answers, such as: fuel used for cooking (electricity; gas; kerosene; coal; others; various), maximum study level attained by the mother (none, basic or primary; incomplete secondary; complete secondary and high school; university), and father and mother social class as classified by the “Social Class based on Occupation” (formerly “Registrar General’s Classification of Occupations”, UK) validated in Spanish.20 This classification is as follows: I. Professional occupations – e.g. doctors and lawyers; II. Managerial and lower professional occupations – e.g. managers and teachers; IIIN. Non-manual skilled occupations – e.g. office workers; IIIM. Manual skilled occupations – e.g. bricklayers, coalminers; IV. Semi-skilled occupations – e.g. postal workers; V. Unskilled occupations – e.g. porters, dustmen. An option for “not working at present”, which included home-maker for women was also included. Parents were asked to report on the number of people living in the household.

Data analysisDescriptive statistics showing the prevalence of the main outcome variables together with that of potential risk/protective factors in each centre were obtained by means of SPSS v10 software (Chicago, IL, USA). The crude association between risk factors and outcome variables (any wheezing episode and recurrent wheezing) was assessed by means of the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% CI were calculated by means of multivariable logistic regression analysis, using generalised linear models with a binomial distribution and logistic link, with all risk/protective factors as independent variables, and any wheezing episode or recurrent wheezing as dependent variables (Stata v7, College Station, TX, USA). The logistic regression model was adjusted for: country; gender; race; eczema in the child (as reported by parents and defined as an itchy rash which was coming and going in any area of his/her body, except around the eyes and nose, and the diaper area, during his/her first 12 months of life); smoking habit of the mother during pregnancy; parental and sibling history of asthma; nasal allergy and eczema; attendance to nursery school; breast feeding (3 or more months as the cut-off point) and having a cold in the first three months of life (defined as: short episodes of runny nose, sneezing, nasal obstruction, mild cough, with or without mild fever). Summary aOR with 95% CI were calculated using the meta-analysis approach with random effects in order to allow for the weight of the centre 21 (Comprehensive Meta-Analysis v2, Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA) for those factors which had a significant (p<0.05) or near significant (p<0.1) positive or negative association with the outcome variables in at least one of the countries.

Ethical approvalThe study was approved by the local Scientific Ethic Committee at each centre, and parents or guardians answered the questionnaire after signing the full-informed written consent.

ResultsThe number of parents answering the questionnaire was 1101 in the centre of San Pedro Sula (participation rate 84.5%) and 1685 in the centre of La Libertad (participation rate 87.2%). After discarding those questionnaires with no answer in the key question about wheezing, or in the number of wheezing episodes, or having the first episode after the age of 12 months; or being younger than 11 months or older than 15 months; the numbers were reduced to 780 (Honduras) and 1047 (EL Salvador).

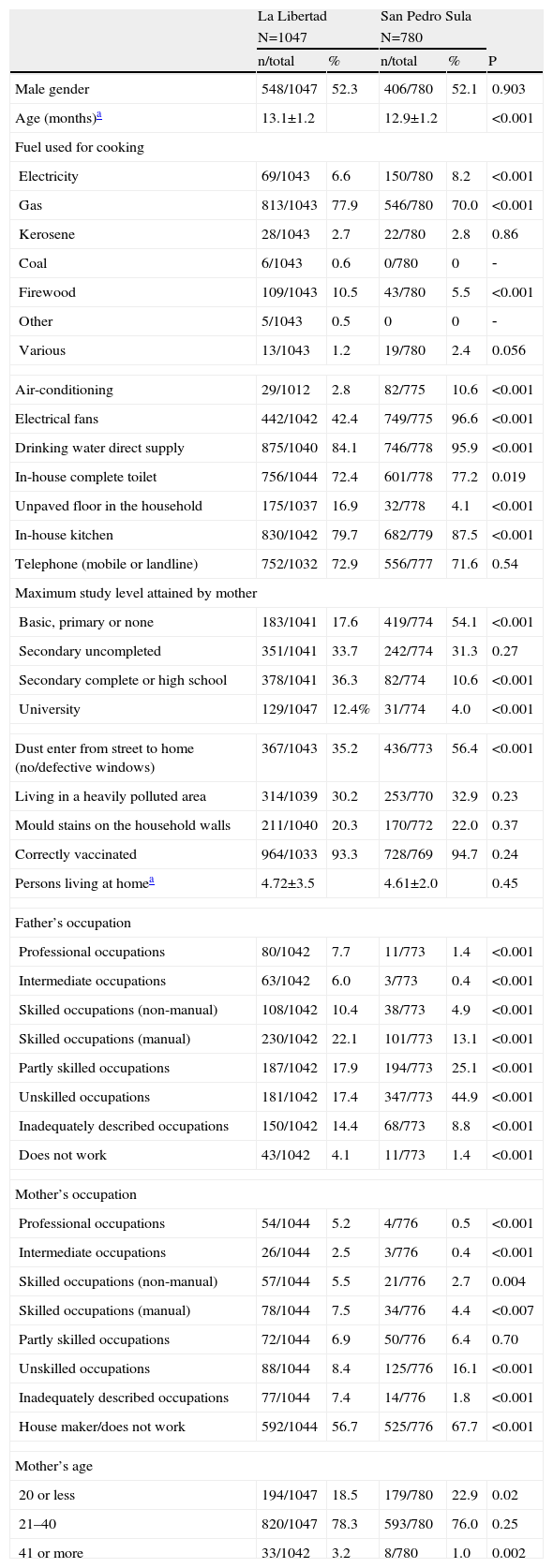

The demographic characteristics of both populations are shown in Table 1. The mean age at the time the questionnaire was filled in was 13.1±1.2 and 12.9±1.2 months for the centres in La Libertad and in San Pedro Sula, respectively. It is noteworthy that in a tropical climate only 2.8% (La Libertad) and 10.6% (San Pedro Sula) of the population reported having air-conditioning at home. Moreover, more than 15% did not have direct connection to drinking water in the surveyed area of La Libertad, less than 80% had a complete toilet in the house (both countries), more than 15% had no paved/concrete floor (usually compacted ground) in the house (La Libertad), and more than 35% reported dust entering easily from the street due to not having proper windows (both countries). Additionally, in both countries, more than 25% did not have a telephone (mobile or land line) and the percentage of mothers having university studies was very low (12.4% in El Salvador and 4.0% in Honduras). It is also important to note that about 20% of them were aged 20 years or less at the time that the questionnaire was filled in.

Demographic characteristics of the studied population by country

| La Libertad | San Pedro Sula | ||||

| N=1047 | N=780 | ||||

| n/total | % | n/total | % | P | |

| Male gender | 548/1047 | 52.3 | 406/780 | 52.1 | 0.903 |

| Age (months)a | 13.1±1.2 | 12.9±1.2 | <0.001 | ||

| Fuel used for cooking | |||||

| Electricity | 69/1043 | 6.6 | 150/780 | 8.2 | <0.001 |

| Gas | 813/1043 | 77.9 | 546/780 | 70.0 | <0.001 |

| Kerosene | 28/1043 | 2.7 | 22/780 | 2.8 | 0.86 |

| Coal | 6/1043 | 0.6 | 0/780 | 0 | ‐ |

| Firewood | 109/1043 | 10.5 | 43/780 | 5.5 | <0.001 |

| Other | 5/1043 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | ‐ |

| Various | 13/1043 | 1.2 | 19/780 | 2.4 | 0.056 |

| Air-conditioning | 29/1012 | 2.8 | 82/775 | 10.6 | <0.001 |

| Electrical fans | 442/1042 | 42.4 | 749/775 | 96.6 | <0.001 |

| Drinking water direct supply | 875/1040 | 84.1 | 746/778 | 95.9 | <0.001 |

| In-house complete toilet | 756/1044 | 72.4 | 601/778 | 77.2 | 0.019 |

| Unpaved floor in the household | 175/1037 | 16.9 | 32/778 | 4.1 | <0.001 |

| In-house kitchen | 830/1042 | 79.7 | 682/779 | 87.5 | <0.001 |

| Telephone (mobile or landline) | 752/1032 | 72.9 | 556/777 | 71.6 | 0.54 |

| Maximum study level attained by mother | |||||

| Basic, primary or none | 183/1041 | 17.6 | 419/774 | 54.1 | <0.001 |

| Secondary uncompleted | 351/1041 | 33.7 | 242/774 | 31.3 | 0.27 |

| Secondary complete or high school | 378/1041 | 36.3 | 82/774 | 10.6 | <0.001 |

| University | 129/1047 | 12.4% | 31/774 | 4.0 | <0.001 |

| Dust enter from street to home (no/defective windows) | 367/1043 | 35.2 | 436/773 | 56.4 | <0.001 |

| Living in a heavily polluted area | 314/1039 | 30.2 | 253/770 | 32.9 | 0.23 |

| Mould stains on the household walls | 211/1040 | 20.3 | 170/772 | 22.0 | 0.37 |

| Correctly vaccinated | 964/1033 | 93.3 | 728/769 | 94.7 | 0.24 |

| Persons living at homea | 4.72±3.5 | 4.61±2.0 | 0.45 | ||

| Father’s occupation | |||||

| Professional occupations | 80/1042 | 7.7 | 11/773 | 1.4 | <0.001 |

| Intermediate occupations | 63/1042 | 6.0 | 3/773 | 0.4 | <0.001 |

| Skilled occupations (non-manual) | 108/1042 | 10.4 | 38/773 | 4.9 | <0.001 |

| Skilled occupations (manual) | 230/1042 | 22.1 | 101/773 | 13.1 | <0.001 |

| Partly skilled occupations | 187/1042 | 17.9 | 194/773 | 25.1 | <0.001 |

| Unskilled occupations | 181/1042 | 17.4 | 347/773 | 44.9 | <0.001 |

| Inadequately described occupations | 150/1042 | 14.4 | 68/773 | 8.8 | <0.001 |

| Does not work | 43/1042 | 4.1 | 11/773 | 1.4 | <0.001 |

| Mother’s occupation | |||||

| Professional occupations | 54/1044 | 5.2 | 4/776 | 0.5 | <0.001 |

| Intermediate occupations | 26/1044 | 2.5 | 3/776 | 0.4 | <0.001 |

| Skilled occupations (non-manual) | 57/1044 | 5.5 | 21/776 | 2.7 | 0.004 |

| Skilled occupations (manual) | 78/1044 | 7.5 | 34/776 | 4.4 | <0.007 |

| Partly skilled occupations | 72/1044 | 6.9 | 50/776 | 6.4 | 0.70 |

| Unskilled occupations | 88/1044 | 8.4 | 125/776 | 16.1 | <0.001 |

| Inadequately described occupations | 77/1044 | 7.4 | 14/776 | 1.8 | <0.001 |

| House maker/does not work | 592/1044 | 56.7 | 525/776 | 67.7 | <0.001 |

| Mother’s age | |||||

| 20 or less | 194/1047 | 18.5 | 179/780 | 22.9 | 0.02 |

| 21–40 | 820/1047 | 78.3 | 593/780 | 76.0 | 0.25 |

| 41 or more | 33/1042 | 3.2 | 8/780 | 1.0 | 0.002 |

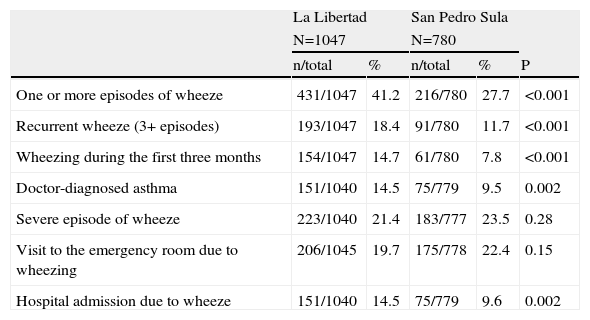

Table 2 shows the prevalence of wheeze and severe wheeze in both study centres. Wheezing in the first year of life, recurrent wheeze (three or more episodes in that period) and wheezing during the first 3 months of life were higher in the centre in La Libertad than in that of San Pedro Sula; while markers of severity were not so different, except for hospital admissions.

Prevalence of wheeze and severe wheeze during the first year of life in both countries

| La Libertad | San Pedro Sula | ||||

| N=1047 | N=780 | ||||

| n/total | % | n/total | % | P | |

| One or more episodes of wheeze | 431/1047 | 41.2 | 216/780 | 27.7 | <0.001 |

| Recurrent wheeze (3+ episodes) | 193/1047 | 18.4 | 91/780 | 11.7 | <0.001 |

| Wheezing during the first three months | 154/1047 | 14.7 | 61/780 | 7.8 | <0.001 |

| Doctor-diagnosed asthma | 151/1040 | 14.5 | 75/779 | 9.5 | 0.002 |

| Severe episode of wheeze | 223/1040 | 21.4 | 183/777 | 23.5 | 0.28 |

| Visit to the emergency room due to wheezing | 206/1045 | 19.7 | 175/778 | 22.4 | 0.15 |

| Hospital admission due to wheeze | 151/1040 | 14.5 | 75/779 | 9.6 | 0.002 |

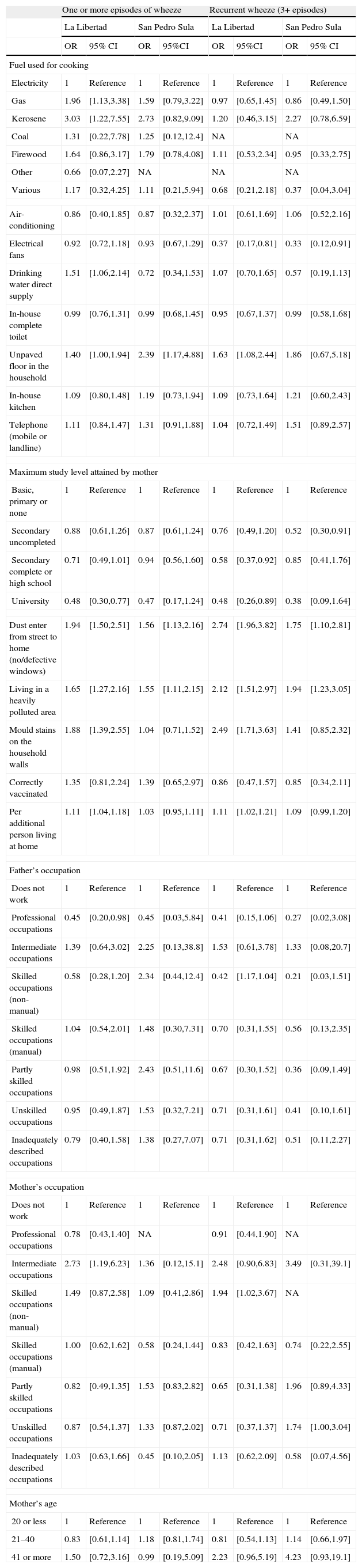

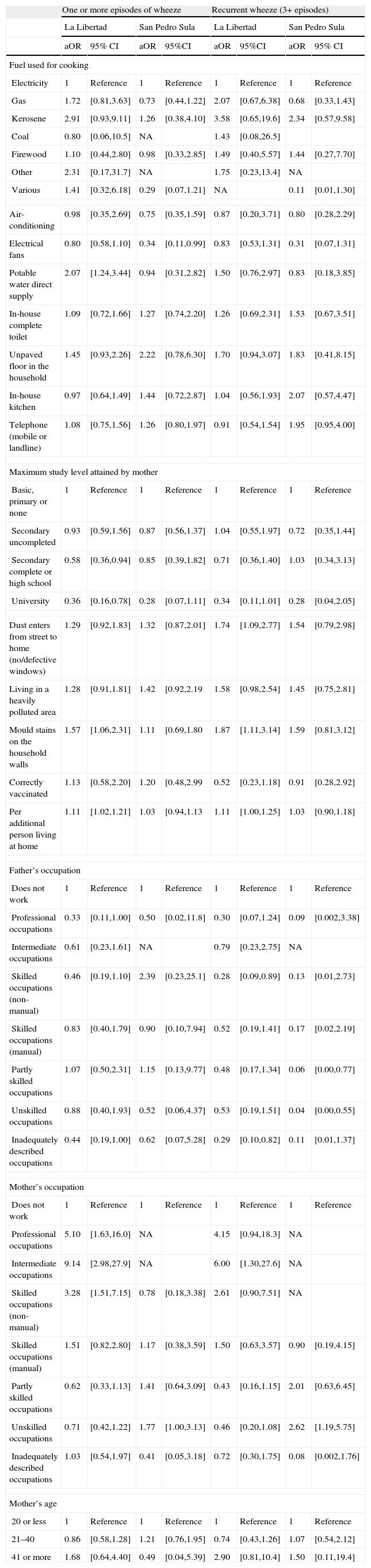

There were a number of associations between the studied factors and suffering from wheezing and recurrent wheezing during the first year of life, according to the bivariable analysis (Table 3). After adjusting for all variables studied here, and also for those which have been previously found to be associated to wheeze in the first year of life, there was a marginal association between using kerosene as cooking fuel (as compared to electricity) and wheeze, only in La Libertad. The protective effect of having electrical fans was also marginal for both countries with respect to any wheezing, but not to recurrent wheezing. Direct potable water supply seemed to be protective only in El Salvador, while having an unpaved floor in the household tended to be positively associated to wheeze and recurrent wheeze in both countries, although not reaching statistical significance. Quite importantly, the effects of university studies in the mother were clearly protective for any wheeze in both countries and for recurrent wheeze in La Libertad. The trend for recurrent wheezing was the same in San Pedro Sula, but the comparatively low numbers of mothers with university studies probably precluded a significant association in this case. Living in a polluted area (as described by parents), having mould stains on the household walls and the increase of people living in the household tended to be positively associated with wheeze and with recurrent wheeze in both countries (sometimes the associations do not reach statistical significance) (Table 4).

Crude associations between wheezing (any number of episodes and recurrent wheeze) and factors associated with poverty in El Salvador and Honduras

| One or more episodes of wheeze | Recurrent wheeze (3+ episodes) | |||||||

| La Libertad | San Pedro Sula | La Libertad | San Pedro Sula | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95%CI | OR | 95%CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Fuel used for cooking | ||||||||

| Electricity | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference |

| Gas | 1.96 | [1.13,3.38] | 1.59 | [0.79,3.22] | 0.97 | [0.65,1.45] | 0.86 | [0.49,1.50] |

| Kerosene | 3.03 | [1.22,7.55] | 2.73 | [0.82,9.09] | 1.20 | [0.46,3.15] | 2.27 | [0.78,6.59] |

| Coal | 1.31 | [0.22,7.78] | 1.25 | [0.12,12.4] | NA | NA | ||

| Firewood | 1.64 | [0.86,3.17] | 1.79 | [0.78,4.08] | 1.11 | [0.53,2.34] | 0.95 | [0.33,2.75] |

| Other | 0.66 | [0.07,2.27] | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Various | 1.17 | [0.32,4.25] | 1.11 | [0.21,5.94] | 0.68 | [0.21,2.18] | 0.37 | [0.04,3.04] |

| Air-conditioning | 0.86 | [0.40,1.85] | 0.87 | [0.32,2.37] | 1.01 | [0.61,1.69] | 1.06 | [0.52,2.16] |

| Electrical fans | 0.92 | [0.72,1.18] | 0.93 | [0.67,1.29] | 0.37 | [0.17,0.81] | 0.33 | [0.12,0.91] |

| Drinking water direct supply | 1.51 | [1.06,2.14] | 0.72 | [0.34,1.53] | 1.07 | [0.70,1.65] | 0.57 | [0.19,1.13] |

| In-house complete toilet | 0.99 | [0.76,1.31] | 0.99 | [0.68,1.45] | 0.95 | [0.67,1.37] | 0.99 | [0.58,1.68] |

| Unpaved floor in the household | 1.40 | [1.00,1.94] | 2.39 | [1.17,4.88] | 1.63 | [1.08,2.44] | 1.86 | [0.67,5.18] |

| In-house kitchen | 1.09 | [0.80,1.48] | 1.19 | [0.73,1.94] | 1.09 | [0.73,1.64] | 1.21 | [0.60,2.43] |

| Telephone (mobile or landline) | 1.11 | [0.84,1.47] | 1.31 | [0.91,1.88] | 1.04 | [0.72,1.49] | 1.51 | [0.89,2.57] |

| Maximum study level attained by mother | ||||||||

| Basic, primary or none | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference |

| Secondary uncompleted | 0.88 | [0.61,1.26] | 0.87 | [0.61,1.24] | 0.76 | [0.49,1.20] | 0.52 | [0.30,0.91] |

| Secondary complete or high school | 0.71 | [0.49,1.01] | 0.94 | [0.56,1.60] | 0.58 | [0.37,0.92] | 0.85 | [0.41,1.76] |

| University | 0.48 | [0.30,0.77] | 0.47 | [0.17,1.24] | 0.48 | [0.26,0.89] | 0.38 | [0.09,1.64] |

| Dust enter from street to home (no/defective windows) | 1.94 | [1.50,2.51] | 1.56 | [1.13,2.16] | 2.74 | [1.96,3.82] | 1.75 | [1.10,2.81] |

| Living in a heavily polluted area | 1.65 | [1.27,2.16] | 1.55 | [1.11,2.15] | 2.12 | [1.51,2.97] | 1.94 | [1.23,3.05] |

| Mould stains on the household walls | 1.88 | [1.39,2.55] | 1.04 | [0.71,1.52] | 2.49 | [1.71,3.63] | 1.41 | [0.85,2.32] |

| Correctly vaccinated | 1.35 | [0.81,2.24] | 1.39 | [0.65,2.97] | 0.86 | [0.47,1.57] | 0.85 | [0.34,2.11] |

| Per additional person living at home | 1.11 | [1.04,1.18] | 1.03 | [0.95,1.11] | 1.11 | [1.02,1.21] | 1.09 | [0.99,1.20] |

| Father’s occupation | ||||||||

| Does not work | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference |

| Professional occupations | 0.45 | [0.20,0.98] | 0.45 | [0.03,5.84] | 0.41 | [0.15,1.06] | 0.27 | [0.02,3.08] |

| Intermediate occupations | 1.39 | [0.64,3.02] | 2.25 | [0.13,38.8] | 1.53 | [0.61,3.78] | 1.33 | [0.08,20.7] |

| Skilled occupations (non-manual) | 0.58 | [0.28,1.20] | 2.34 | [0.44,12.4] | 0.42 | [1.17,1.04] | 0.21 | [0.03,1.51] |

| Skilled occupations (manual) | 1.04 | [0.54,2.01] | 1.48 | [0.30,7.31] | 0.70 | [0.31,1.55] | 0.56 | [0.13,2.35] |

| Partly skilled occupations | 0.98 | [0.51,1.92] | 2.43 | [0.51,11.6] | 0.67 | [0.30,1.52] | 0.36 | [0.09,1.49] |

| Unskilled occupations | 0.95 | [0.49,1.87] | 1.53 | [0.32,7.21] | 0.71 | [0.31,1.61] | 0.41 | [0.10,1.61] |

| Inadequately described occupations | 0.79 | [0.40,1.58] | 1.38 | [0.27,7.07] | 0.71 | [0.31,1.62] | 0.51 | [0.11,2.27] |

| Mother’s occupation | ||||||||

| Does not work | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference |

| Professional occupations | 0.78 | [0.43,1.40] | NA | 0.91 | [0.44,1.90] | NA | ||

| Intermediate occupations | 2.73 | [1.19,6.23] | 1.36 | [0.12,15.1] | 2.48 | [0.90,6.83] | 3.49 | [0.31,39.1] |

| Skilled occupations (non-manual) | 1.49 | [0.87,2.58] | 1.09 | [0.41,2.86] | 1.94 | [1.02,3.67] | NA | |

| Skilled occupations (manual) | 1.00 | [0.62,1.62] | 0.58 | [0.24,1.44] | 0.83 | [0.42,1.63] | 0.74 | [0.22,2.55] |

| Partly skilled occupations | 0.82 | [0.49,1.35] | 1.53 | [0.83,2.82] | 0.65 | [0.31,1.38] | 1.96 | [0.89,4.33] |

| Unskilled occupations | 0.87 | [0.54,1.37] | 1.33 | [0.87,2.02] | 0.71 | [0.37,1.37] | 1.74 | [1.00,3.04] |

| Inadequately described occupations | 1.03 | [0.63,1.66] | 0.45 | [0.10,2.05] | 1.13 | [0.62,2.09] | 0.58 | [0.07,4.56] |

| Mother’s age | ||||||||

| 20 or less | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference |

| 21–40 | 0.83 | [0.61,1.14] | 1.18 | [0.81,1.74] | 0.81 | [0.54,1.13] | 1.14 | [0.66,1.97] |

| 41 or more | 1.50 | [0.72,3.16] | 0.99 | [0.19,5.09] | 2.23 | [0.96,5.19] | 4.23 | [0.93,19.1] |

NA: Not available due to reduced number of individuals in that particular stratum.

Adjusteda associations between wheezing (any number of episodes, occasional wheeze and recurrent wheeze) and factors associated with poverty in El Salvador

| One or more episodes of wheeze | Recurrent wheeze (3+ episodes) | |||||||

| La Libertad | San Pedro Sula | La Libertad | San Pedro Sula | |||||

| aOR | 95% CI | aOR | 95%CI | aOR | 95%CI | aOR | 95% CI | |

| Fuel used for cooking | ||||||||

| Electricity | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference |

| Gas | 1.72 | [0.81,3.63] | 0.73 | [0.44,1.22] | 2.07 | [0.67,6.38] | 0.68 | [0.33,1.43] |

| Kerosene | 2.91 | [0.93,9.11] | 1.26 | [0.38,4.10] | 3.58 | [0.65,19.6] | 2.34 | [0.57,9.58] |

| Coal | 0.80 | [0.06,10.5] | NA | 1.43 | [0.08,26.5] | |||

| Firewood | 1.10 | [0.44,2.80] | 0.98 | [0.33,2.85] | 1.49 | [0.40,5.57] | 1.44 | [0.27,7.70] |

| Other | 2.31 | [0.17,31.7] | NA | 1.75 | [0.23,13.4] | NA | ||

| Various | 1.41 | [0.32,6.18] | 0.29 | [0.07,1.21] | NA | 0.11 | [0.01,1.30] | |

| Air-conditioning | 0.98 | [0.35,2.69] | 0.75 | [0.35,1.59] | 0.87 | [0.20,3.71] | 0.80 | [0.28,2.29] |

| Electrical fans | 0.80 | [0.58,1.10] | 0.34 | [0.11,0.99] | 0.83 | [0.53,1.31] | 0.31 | [0.07,1.31] |

| Potable water direct supply | 2.07 | [1.24,3.44] | 0.94 | [0.31,2.82] | 1.50 | [0.76,2.97] | 0.83 | [0.18,3.85] |

| In-house complete toilet | 1.09 | [0.72,1.66] | 1.27 | [0.74,2.20] | 1.26 | [0.69,2.31] | 1.53 | [0.67,3.51] |

| Unpaved floor in the household | 1.45 | [0.93,2.26] | 2.22 | [0.78,6.30] | 1.70 | [0.94,3.07] | 1.83 | [0.41,8.15] |

| In-house kitchen | 0.97 | [0.64,1.49] | 1.44 | [0.72,2.87] | 1.04 | [0.56,1.93] | 2.07 | [0.57,4.47] |

| Telephone (mobile or landline) | 1.08 | [0.75,1.56] | 1.26 | [0.80,1.97] | 0.91 | [0.54,1.54] | 1.95 | [0.95,4.00] |

| Maximum study level attained by mother | ||||||||

| Basic, primary or none | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference |

| Secondary uncompleted | 0.93 | [0.59,1.56] | 0.87 | [0.56,1.37] | 1.04 | [0.55,1.97] | 0.72 | [0.35,1.44] |

| Secondary complete or high school | 0.58 | [0.36,0.94] | 0.85 | [0.39,1.82] | 0.71 | [0.36,1.40] | 1.03 | [0.34,3.13] |

| University | 0.36 | [0.16,0.78] | 0.28 | [0.07,1.11] | 0.34 | [0.11,1.01] | 0.28 | [0.04,2.05] |

| Dust enters from street to home (no/defective windows) | 1.29 | [0.92,1.83] | 1.32 | [0.87,2.01] | 1.74 | [1.09,2.77] | 1.54 | [0.79,2.98] |

| Living in a heavily polluted area | 1.28 | [0.91,1.81] | 1.42 | [0.92,2.19 | 1.58 | [0.98,2.54] | 1.45 | [0.75,2.81] |

| Mould stains on the household walls | 1.57 | [1.06,2.31] | 1.11 | [0.69,1.80 | 1.87 | [1.11,3.14] | 1.59 | [0.81,3.12] |

| Correctly vaccinated | 1.13 | [0.58,2.20] | 1.20 | [0.48,2.99 | 0.52 | [0.23,1.18] | 0.91 | [0.28,2.92] |

| Per additional person living at home | 1.11 | [1.02,1.21] | 1.03 | [0.94,1.13 | 1.11 | [1.00,1.25] | 1.03 | [0.90,1.18] |

| Father’s occupation | ||||||||

| Does not work | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference |

| Professional occupations | 0.33 | [0.11,1.00] | 0.50 | [0.02,11.8] | 0.30 | [0.07,1.24] | 0.09 | [0.002,3.38] |

| Intermediate occupations | 0.61 | [0.23,1.61] | NA | 0.79 | [0.23,2.75] | NA | ||

| Skilled occupations (non-manual) | 0.46 | [0.19,1.10] | 2.39 | [0.23,25.1] | 0.28 | [0.09,0.89] | 0.13 | [0.01,2.73] |

| Skilled occupations (manual) | 0.83 | [0.40,1.79] | 0.90 | [0.10,7.94] | 0.52 | [0.19,1.41] | 0.17 | [0.02,2.19] |

| Partly skilled occupations | 1.07 | [0.50,2.31] | 1.15 | [0.13,9.77] | 0.48 | [0.17,1.34] | 0.06 | [0.00,0.77] |

| Unskilled occupations | 0.88 | [0.40,1.93] | 0.52 | [0.06,4.37] | 0.53 | [0.19,1.51] | 0.04 | [0.00,0.55] |

| Inadequately described occupations | 0.44 | [0.19,1.00] | 0.62 | [0.07,5.28] | 0.29 | [0.10,0.82] | 0.11 | [0.01,1.37] |

| Mother’s occupation | ||||||||

| Does not work | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference |

| Professional occupations | 5.10 | [1.63,16.0] | NA | 4.15 | [0.94,18.3] | NA | ||

| Intermediate occupations | 9.14 | [2.98,27.9] | NA | 6.00 | [1.30,27.6] | NA | ||

| Skilled occupations (non-manual) | 3.28 | [1.51,7.15] | 0.78 | [0.18,3.38] | 2.61 | [0.90,7.51] | NA | |

| Skilled occupations (manual) | 1.51 | [0.82,2.80] | 1.17 | [0.38,3.59] | 1.50 | [0.63,3.57] | 0.90 | [0.19,4.15] |

| Partly skilled occupations | 0.62 | [0.33,1.13] | 1.41 | [0.64,3.09] | 0.43 | [0.16,1.15] | 2.01 | [0.63,6.45] |

| Unskilled occupations | 0.71 | [0.42,1.22] | 1.77 | [1.00,3.13] | 0.46 | [0.20,1.08] | 2.62 | [1.19,5.75] |

| Inadequately described occupations | 1.03 | [0.54,1.97] | 0.41 | [0.05,3.18] | 0.72 | [0.30,1.75] | 0.08 | [0.002,1.76] |

| Mother’s age | ||||||||

| 20 or less | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference |

| 21–40 | 0.86 | [0.58,1.28] | 1.21 | [0.76,1.95] | 0.74 | [0.43,1.26] | 1.07 | [0.54,2.12] |

| 41 or more | 1.68 | [0.64,4.40] | 0.49 | [0.04,5.39] | 2.90 | [0.81,10.4] | 1.50 | [0.11,19.4] |

NA: Not available due to reduced number of individuals in that particular stratum.

The summary adjusted odd ratios according to the meta-analysis are shown in Table 5. Combining the power of both sample populations resulted in a clearer picture: there were several positive associations (unpaved floor, dust entering from the streets, heavily polluted area and mould stains in the walls of the house) and two negative ones: mother having university studies and father having a professional occupation. Two other factors remained on the limit of significance: number of persons living at home and use of kerosene for cooking.

Summary odds ratios, according to the meta-analysis, of those factors found statistically significant or near significant in at least one of the countries and with data available in the other

| One or more episodes of wheeze | Recurrent wheeze (3+ episodes) | |||||

| sOR | 95% CI | P | sOR | 95%CI | P | |

| Kerosene for cooking (as compared to electricity) | 1.95 | [0.85,4.44] | 0.112 | 2.78 | [0.94,8.25] | 0.065 |

| Electrical fans | 0.62 | [0.28,1.33] | 0.220 | 0.66 | [0.29,1.49] | 0.315 |

| Potable water direct supply | 1.63 | [0.80,3.32] | 0.175 | 1.36 | [0.73,2.53] | 0.333 |

| Unpaved floor in the household | 1.55 | [1.03,2.33] | 0.036 | 1.72 | [0.99,2.98] | 0.054 |

| University studies (as compared to basic) | 0.34 | [0.17,0.67] | 0.002 | 0.32 | [0.12,0.85] | 0.022 |

| Professional occupation of father (as compared to unemployed) | 0.34 | [0.12,0.98] | 0.046 | 0.26 | [0.07,0.89] | 0.047 |

| Dust enters from street to home (no/defective windows) | 1.30 | [1.00,1.70] | 0.052 | 1.67 | [1.14,2.45] | 0.008 |

| Living in a heavily polluted area | 1.33 | [1.02,1.74] | 0.037 | 1.52 | [1.03,2.14] | 0.033 |

| Mould stains on the household walls | 1.36 | [0.97,1.90] | 0.072 | 1.76 | [1.17,2.66] | 0.007 |

| Per additional person living at home | 1.07 | [0.99,1.15] | 0.065 | 1.07 | [0.98,1.17] | 0.108 |

The present paper shows that in apparently comparable environmental circumstances, the prevalence of wheezing during the first year of life may be quite different. Although as a country Honduras has a lower economic level, it is quite possible that the population studied in this country had better socio-economic level than that studied in El Salvador, as shown in the percentage of air-conditioning devices, electrical fans, in-house complete toilets, paved floor in the houses and direct drinking water supply; all of them significantly higher in San Pedro Sula than in La Libertad. These findings underline the importance of the local environmental factors in the prevalence of early wheeze. Similarly, the local or regional ways of dealing with this condition together with the availability of health facilities may also influence its severity indicators, such as emergency visits or hospital admissions. Overall, it seems that wheezing and recurrent wheezing are more prevalent in El Salvador, while the prevalence of severe episodes is comparable.

The results of the present study also show that several markers of low socio-economic status (mother with basic as compared to university studies, unemployed fathers as compared to professional occupations) and also some situations which are most probably related to low income (unpaved floor in the house, dust entering from streets to houses, mould stains) are independently associated to wheeze in the first year of life, after controlling for other known risk/protective factors. Low socio-economic status in general has been previously reported in affluent countries such as Denmark (2), the United Kingdom (6) and also in Chile (1), as being associated with wheezing during the first months of life. Low socioeconomic status was measured either as living in a low income area (Denmark and Chile) or in a rented local authority housing (UK).

Factors related to low income have also been studied in relation to wheezing during the first years of life, although the information restricted to the infant period is quite scarce. Crowding (measured as >1 person per room) was associated with a higher prevalence of wheeze during the first 6 months of life in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood (ALSPAC) study.22 Conversely, several studies have found that crowding – measured in several different ways – is associated with a lower prevalence of wheezing or asthma at older ages both in affluent and non-affluent countries 23–26, including preschool and primary school ages.27 This situation probably reflects the fact that wheezing has several phenotypes, and while an early and transient phenotype could be boosted by crowding (most probably through increasing the chances of viral respiratory infections), a later or persistent phenotype could be prevented (via shifting of the Th1/Th2 balance of the immune system to the Th1 end). In the present study, an additional person at home was a marginal risk factor both for any wheeze and for recurrent wheeze during the first year of life.

An additional factor which is probably associated with respiratory infections is the presence of a higher indoor relative humidity, as measured by the presence of mould stains on the household walls. The presence of those organisms has been consistently associated to a higher prevalence of asthma symptoms in school and preschool ages 28–30, also in one non-affluent country, Kenya 26, even after controlling for house dust mites growing.31 However, studies restricted to the first months of life are again very scarce.13 Interestingly, in the present study, the association was highest with recurrent wheeze, thus indicating that moulds might be associated to wheeze persistency.31,32 Moulds may not only be a marker of a better growing environment for some viruses (rhinoviruses have a higher survival in greater relative humidity 33 and RSV has a higher activity at relative humidity between 45–65%), but also that they might act enhancing allergy 34, thus favouring asthma persistency in later ages. Furthermore, the non-allergic pro-inflammatory action of spores on the infant airway through macrophage activation should not be forgotten.35

Three factors that may act through direct aggression on the airway and which are significantly associated with a higher prevalence of wheeze are unpaved floor in the household; dust entering from street; and living in a heavily polluted area. Air pollution – other than tobacco smoke – has been described as a risk factor for asthma in children, although this may depend on the dose and type. A study from Romania reported a significant lowering of the prevalence of wheeze during the first year of life after an iron, steel, and coke factory was closed.12 More recently significant positive associations have been found of PM(10), NO(2), NO(x), CO with wheezing symptoms in infants (aged 0–1 year) with a gap of 3–4 days-delay.36 On the other hand, traffic-related pollution has been associated with respiratory infections and some measures of asthma and allergy during the first four years of life.37 Those findings support the results of the present study, in which pollution was self-reported by parents, in countries where no heating systems are usually needed, and after controlling for different cooking fuels such as gas, kerosene, coal or firewood. Those fuels were not associated with wheezing as compared to electricity (although kerosene did show a certain trend which was probably not significant due to the reduced number of households using it). The effect of the smoking habit of the mother during pregnancy – which anyway was used as a confounding variable in the multiple logistic regression – was difficult to assess in our population as the number of smoking mothers during pregnancy was very low (n=27 in La Libertad and n=9 in San Pedro Sula)

Independently of other housing conditions, dust entering easily from street to the house was associated to a higher prevalence of wheeze in the present study. This can be a marker of bad house insulation, thus facilitating outdoor pollution entering the infant environment. However, the irritant effect of mineral dust (which may be further increased when there is no paved floor in the house –another independent risk factor) should not be overlooked; and although there was no information related to infant wheeze, it has been studied as a risk factor of occupational asthma in adults.38

Mother and father occupations and mother education are also factors independently associated to wheezing. Higher mother education, professional occupations (doctors, lawyers, etc.) of the father and house-making occupation of the mother (La Libertad) are independently associated with less wheezing prevalence. A higher parental education has been shown to be associated to a lower prevalence of last year wheeze in schoolchildren from Eastern Europe.39 The authors of this report claim that higher education can increase reporting while low education could be a marker of children being exposed to more and/or higher doses of risk factors. Although we did not find any previous information in the literature as to how maternal education can affect wheezing in the first year of life, the previous rationale might most probably be applied. Mother remaining at home is also (La Libertad, no data available in San Pedro Sula) independently associated with lower prevalence of wheezing during the first year of life. Although there is a very strong association between not working and the infant not attending a day-care facility (data not shown), this factor was adjusted for in the multivariable logistic regression, and mother remaining at home was still a protective factor, which probably means that mother caring is beneficial as compared to foster care.

The present study has several limitations which should be considered when interpreting the results. As a crossover study, no causal relationships can be inferred. Furthermore, all the information analysed wherein was supplied by parents through a questionnaire, and although the outcome variable has been validated in the Spanish language both in Latin America (Chile) and Spain19, its validity might change in Central America. Other information supplied by parents which is highly subjective is that about air pollution. Its association with wheezing during the first year of life seems to be in the anticipated direction, so having it as an adjusting variable is probably worthy. Further information obtained by the questionnaire, although being objective, might be in some way affected by information bias (which may vary according to the educational level), as it occurs with most epidemiological studies. On the other hand, the sample is big enough and the participation rate is high enough to offer robust results. Additionally, several factors associated in the present study with a higher prevalence of wheezing have been found to be so in previous ones, this consistency adding some value to the results obtained with non-previously tested factors.

In summary, the present study shows that the prevalence of wheezing during the first year of life in two low-resourced countries of Central America is quite high and that low educational level together with several situations related to low income are independently associated to an increased risk of suffering from early wheeze.

Funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation, grants A/8585/07 and A/8579/07; and grant 11663/EE2/09 from the Seneca Foundation and Technology & Science Agency, Murcia Region, Spain (II PCTRM 2007–2010). We are grateful to Mr. Anthony Carlson for his help with the English version of the present paper.