Primary immunodeficiency diseases (PID) are a heterogeneous group of inherited disorders, characterised by recurrent severe infections, autoimmunity and lymphoproliferation. Despite impressive progress in identification of novel PID, there is an unfortunate lack of awareness among physicians in identification of patients with PID, especially in non-capital cities of countries worldwide.

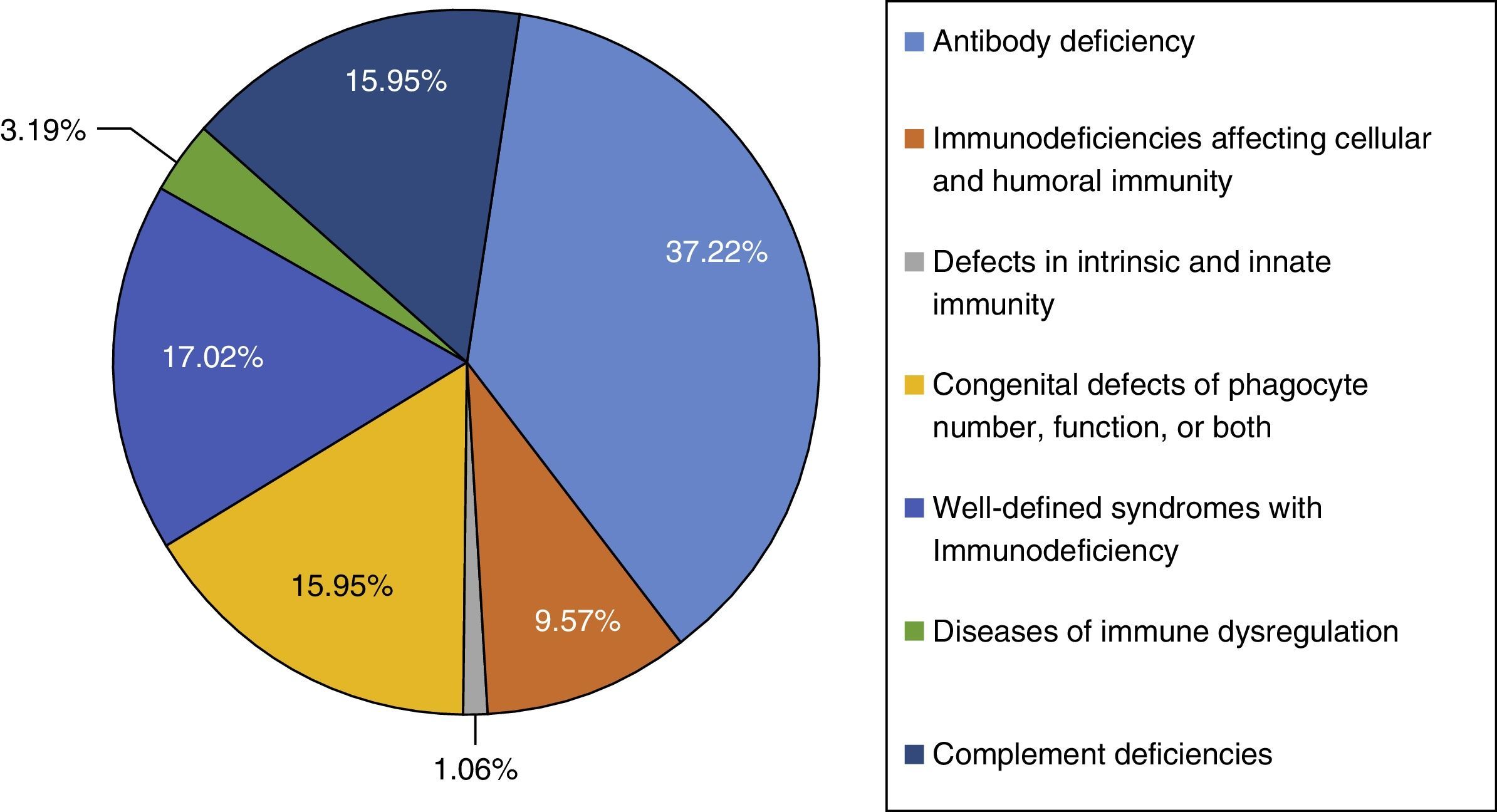

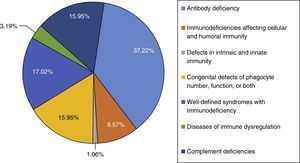

ResultThis study was performed in a single-centre paediatric hospital in Northern Iran during a 21-year period (1994–2015). Ninety-four patients were included in this study. The majority of cases had antibody deficiencies (37.23%), followed by well-defined syndromes with immunodeficiency in 16 (17.02%), phagocytic disorders in 15 patients (15.95%), complement deficiencies in 15 patients (15.95%), immunodeficiencies affecting cellular and humoral immunity in nine patients (9.57%), disease of immune dysregulation in three (3.19%), and defects in intrinsic and innate immunity in one (1.06%).

ConclusionIt seems that there are major variations in frequency of different types of PID in different regions of a country. Therefore, reporting local data could provide better ideas to improve the local health care system strategists and quality of care of PID patients.

Primary immunodeficiency diseases (PIDs) are a heterogeneous group of disorders, characterised by increased susceptibility to recurrent infections and malignancies.1,2 As a result in improvements in immunological and molecular diagnostic methods, more than 300 different PIDs have been currently identified.3–5 Despite the increasing trend in diagnosis of patients with PID, lack of awareness among physicians continues to play an important role in the delay of diagnosis in this group of patients.6–8 This in turn will delay the initiation of appropriate treatments and lead to increases in morbidity and mortality.6,7 Therefore, evaluation of immune function is required for patients who present with unusual, chronic or recurrent clinical manifestations such as severe systemic bacterial infection, serious upper and lower respiratory tract infections and liver or brain abscesses.

Since 1999, the Iranian Primary Immunodeficiency Registry (IPIDR) has collected data in order to estimate the prevalence of various types of PID in Iran.9 According to epidemiological studies, wide variations exist in geographical and racial prevalence as well as in the frequency of different types of PID.10–15 Therefore, regional data regarding the prevalence of various types of PID can work as a powerful tool in improving the local health care system strategies and quality of care of patients diagnosed with PID.16 The aim of our study was therefore to determine the frequency of PID in Northern Iran over a period of 21 years from 1994 to 2015.

Patients and methodsIn the present study, we analysed the medical charts of 94 patients with PID who were referred to the allergy/immunology clinic in Amir-Kola Hospital in Babol, Mazandaran, province of Iran, over a period of 21 years (1994–2015). All patients were diagnosed with immunodeficiency according to Pan-American Group for Immunodeficiency (PAGID) and European society for immunodeficiencies (ESID) criteria.17

Secondary causes of immunodeficiency such as Patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection, organ transplantation or radiotherapy were excluded using standardised laboratory tests. A questionnaire was designed to collect information regarding demographic data including name, age, sex, consanguinity of parents, family history of any immunological disorders, age of onset, age at time of PID diagnosis and recurrent episodes of infections.

Laboratory analysis contained complete blood count performed by automated blood counting machine, Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) measured by Western Green Method, haemagglutinins measured by CA1600 and serum immunoglobulin levels (IgG, IgE, IgA, and IgM) measured by Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay (ELISA), reviewing Cluster of Differentiation (CD) markers done by flow cytometry, the level of serum complement components (C3, C4, CH50) measured by ELISA, delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions test (purified protein derivative), lymphocyte transformation test, isohaemagglutinin tests, IgG subclasses serum level, evaluation of lymphocyte subtypes, chemotaxis evaluation, nitro blue tetrazolium dye test and haemolytic titration of complement (CH50) as needed.

Definitions of different immunodeficiency disorders were made according to the following criteria: Impaired T-cell function was defined by absence of lymphocyte proliferation cells in response to mitogens (e.g., PHA) and antigens, with normal T lymphocyte count. CD4 deficiency was defined as isolated absence of CD4 T-cell (or very low count) without any evidence of secondary immunodeficiency (HIV infection) or other known immunodeficiency (normal expression of HLADR). CD8 deficiency was defined as isolated absence of CD8 T-cell. Patients were considered to have HIGM if they had serum IgG concentrations at least two standard deviations below normal for their age and a confirmed mutation in any of the following genes: CD40LG (XHIGM) or AICDA, CD40, UNG (all ARHIGM), or PIK3CD (ADHIGM). The diagnosis of CVID was made with decreased serum IgG, IgM and/or IgA level, decreased response to vaccines, a B cell number more than 1% of total lymphocytes, age older than four years old at the time of diagnosis, and exclusion of other causes of hypogammaglobulinaemia. All DiGeorge syndrome cases were confirmed by chromosomal analysis that had been fully analysed by conventional and G-banding methods. The 22q11.2 deletion was confirmed using fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) with a commercially-available region-specific probe (Vysis LSI D22S75 (N25 region) Spectrum Orange/LSI ARSA SpectrumGreen).

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Babol. All the data were analysed by statistical software SPSS-19.

ResultsNinety-four PID patients, 56 males and 38 females, were enrolled in our study. The male-to-female ratio was 1.47:1. As shown in Fig. 1, patients were classified into seven main groups of PID according to the International Union of Immunological Societies (IUIS) classification5 (Fig. 1). At the time of diagnosis, 84 patients (89.36%) were under the age of 16 years. The mean age of patients at the onset of symptoms was 4.52±9.68 years and the mean age at the time of diagnosis was 6.79±10.34 years. The youngest patient registered was one month old while the oldest presented at 69 years of age. The mean gap between diagnostic delay for a number of PIDs such as common variable immunodeficiency (CVID), X-linked agammaglobulinaemia (XLA) and chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) were 43.9 months, 19.5 months and 21 months, respectively.

The majority of cases in the present cohort had antibody deficiencies, being present in 35 patients (37.23%), followed by well-defined syndromes with immunodeficiency in 16 (17.02%), phagocytic disorders in 15 patients (15.95%), complement deficiencies in 15 patients (15.95%), immunodeficiencies affecting cellular and humoral immunity in nine patients (9.57%), disease of immune dysregulation in three (3.19%), and defects in intrinsic and innate immunity in one (1.06%) (Fig. 1).

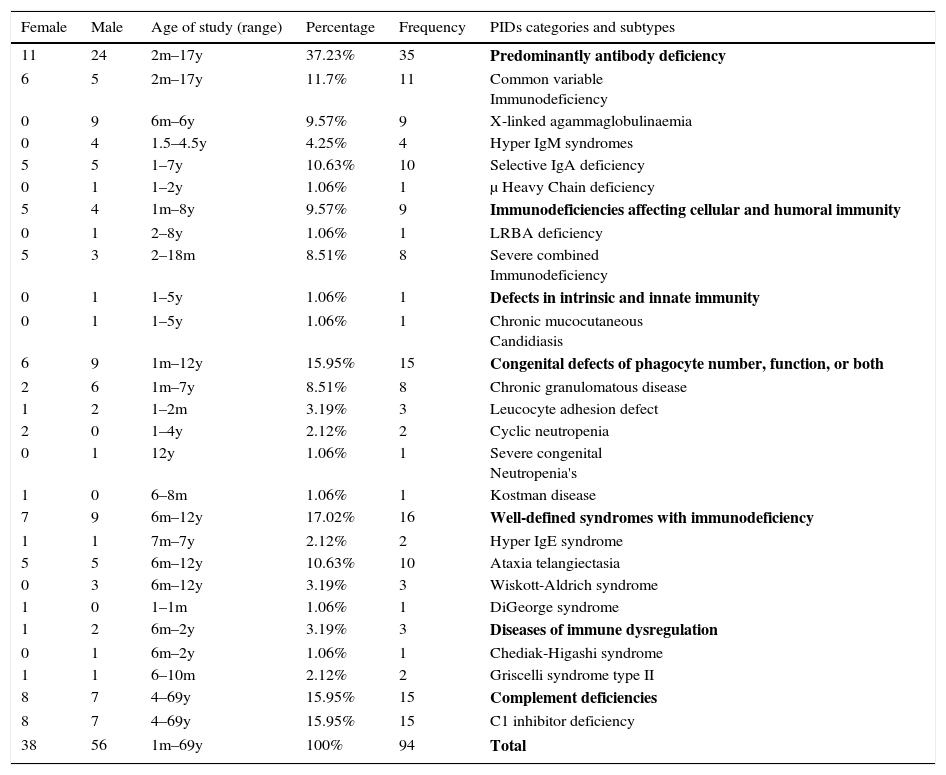

Among all patients, 22 (23.40%) died, while three (3.19%) were inaccessible for their last follow up. The majority of patients belonged to the paediatric age group (93.2%). The frequency and demographic variations of different types of PID are demonstrated in Table 1.

Frequency and demographic data of 94 PID patients by phenotype.

| Female | Male | Age of study (range) | Percentage | Frequency | PIDs categories and subtypes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 24 | 2m–17y | 37.23% | 35 | Predominantly antibody deficiency |

| 6 | 5 | 2m–17y | 11.7% | 11 | Common variable Immunodeficiency |

| 0 | 9 | 6m–6y | 9.57% | 9 | X-linked agammaglobulinaemia |

| 0 | 4 | 1.5–4.5y | 4.25% | 4 | Hyper IgM syndromes |

| 5 | 5 | 1–7y | 10.63% | 10 | Selective IgA deficiency |

| 0 | 1 | 1–2y | 1.06% | 1 | μ Heavy Chain deficiency |

| 5 | 4 | 1m–8y | 9.57% | 9 | Immunodeficiencies affecting cellular and humoral immunity |

| 0 | 1 | 2–8y | 1.06% | 1 | LRBA deficiency |

| 5 | 3 | 2–18m | 8.51% | 8 | Severe combined Immunodeficiency |

| 0 | 1 | 1–5y | 1.06% | 1 | Defects in intrinsic and innate immunity |

| 0 | 1 | 1–5y | 1.06% | 1 | Chronic mucocutaneous Candidiasis |

| 6 | 9 | 1m–12y | 15.95% | 15 | Congenital defects of phagocyte number, function, or both |

| 2 | 6 | 1m–7y | 8.51% | 8 | Chronic granulomatous disease |

| 1 | 2 | 1–2m | 3.19% | 3 | Leucocyte adhesion defect |

| 2 | 0 | 1–4y | 2.12% | 2 | Cyclic neutropenia |

| 0 | 1 | 12y | 1.06% | 1 | Severe congenital Neutropenia's |

| 1 | 0 | 6–8m | 1.06% | 1 | Kostman disease |

| 7 | 9 | 6m–12y | 17.02% | 16 | Well-defined syndromes with immunodeficiency |

| 1 | 1 | 7m–7y | 2.12% | 2 | Hyper IgE syndrome |

| 5 | 5 | 6m–12y | 10.63% | 10 | Ataxia telangiectasia |

| 0 | 3 | 6m–12y | 3.19% | 3 | Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome |

| 1 | 0 | 1–1m | 1.06% | 1 | DiGeorge syndrome |

| 1 | 2 | 6m–2y | 3.19% | 3 | Diseases of immune dysregulation |

| 0 | 1 | 6m–2y | 1.06% | 1 | Chediak-Higashi syndrome |

| 1 | 1 | 6–10m | 2.12% | 2 | Griscelli syndrome type II |

| 8 | 7 | 4–69y | 15.95% | 15 | Complement deficiencies |

| 8 | 7 | 4–69y | 15.95% | 15 | C1 inhibitor deficiency |

| 38 | 56 | 1m–69y | 100% | 94 | Total |

m: months; y: years.

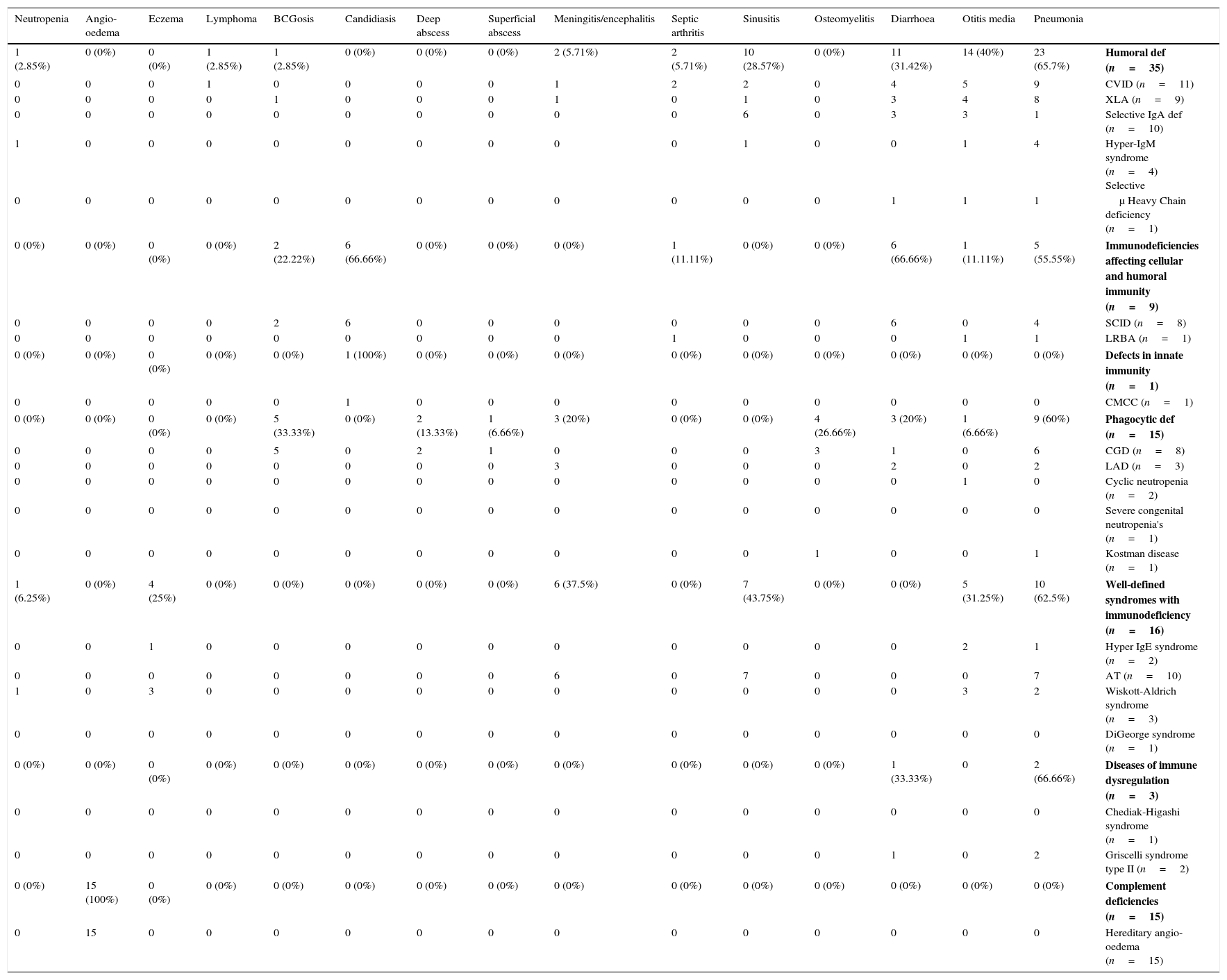

From all patients registered in this study, antibody deficiencies were the most prevalent immunodeficiency disorders, diagnosed in 35 cases which consisted of common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) in 11 cases, X-linked agammaglobulinaemia (XLA) in nine cases, selective IgA deficiency in 10 cases, hyper-IgM syndrome in four patients and μ Heavy Chain deficiency in only one patient. Among these patients, the most frequent infectious manifestation of CVID patients was pneumonia followed by diarrhoea, otitis media and upper respiratory tract infections, respectively (Table 2). For patients diagnosed with XLA, severe upper and lower respiratory tract infections were the most common infectious manifestation. The main symptom of Hyper-IgM syndrome was sinopulmonary infections.

Frequency of common infection in different phenotypes of 94 patients with primary immunodeficiency disorders.

| Neutropenia | Angio-oedema | Eczema | Lymphoma | BCGosis | Candidiasis | Deep abscess | Superficial abscess | Meningitis/encephalitis | Septic arthritis | Sinusitis | Osteomyelitis | Diarrhoea | Otitis media | Pneumonia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (2.85%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.85%) | 1 (2.85%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (5.71%) | 2 (5.71%) | 10 (28.57%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (31.42%) | 14 (40%) | 23 (65.7%) | Humoral def (n=35) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 9 | CVID (n=11) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 8 | XLA (n=9) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | Selective IgA def (n=10) |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | Hyper-IgM syndrome (n=4) Selective |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | μ Heavy Chain deficiency (n=1) |

| 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (22.22%) | 6 (66.66%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (11.11%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (66.66%) | 1 (11.11%) | 5 (55.55%) | Immunodeficiencies affecting cellular and humoral immunity (n=9) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 4 | SCID (n=8) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | LRBA (n=1) |

| 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | Defects in innate immunity (n=1) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | CMCC (n=1) |

| 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (33.33%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (13.33%) | 1 (6.66%) | 3 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (26.66%) | 3 (20%) | 1 (6.66%) | 9 (60%) | Phagocytic def (n=15) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 6 | CGD (n=8) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | LAD (n=3) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Cyclic neutropenia (n=2) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Severe congenital neutropenia's (n=1) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Kostman disease (n=1) |

| 1 (6.25%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (37.5%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (43.75%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (31.25%) | 10 (62.5%) | Well-defined syndromes with immunodeficiency (n=16) |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | Hyper IgE syndrome (n=2) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | AT (n=10) |

| 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (n=3) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | DiGeorge syndrome (n=1) |

| 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (33.33%) | 0 | 2 (66.66%) | Diseases of immune dysregulation (n=3) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Chediak-Higashi syndrome (n=1) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | Griscelli syndrome type II (n=2) |

| 0 (0%) | 15 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | Complement deficiencies (n=15) |

| 0 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Hereditary angio-oedema (n=15) |

The frequency of the well-defined immunodeficiency syndromes was 16 (17.02%), including ataxia telangiectasia (AT) in 10 patients. Their main clinical presentations were pneumonia (62.5%) followed by sinusitis (43.75%).

Fifteen patients (15.95%) had phagocytic disorders including chronic granulomatous disease in eight patients, Leucocyte adhesion defect in three, cyclic neutropenia in two, severe congenital neutropenia in one and Kostman disease in one. The most common clinical features among this group were pneumonia, BCGosis, osteomyelitis, diarrhoea, meningitis and otitis media respectively.

Immunodeficiencies affecting cellular and humoral immunity were diagnosed in nine patients (9.57%) with the majority diagnosed with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) with candidiasis being the most predominant symptom in six patients (66.66%). Other symptoms including diarrhoea and pneumonia were detected in six and four patients, respectively.

Among patients with complement deficiencies, 15 patients (15.95%) were diagnosed with hereditary angio-oedema. In almost all of these patients, no significant infectious manifestation was present, with angio-oedema being their only clinical presentation at the time of diagnosis.

Disease of immune dysregulation involved three cases (3.19%), including two cases of Griscelli syndrome type 2 and one case of Chediak-Higashi syndrome. Both cases of Griscelli syndrome type 2 died due to the severe respiratory tract infection.

DiscussionIn the present report, we evaluated the frequency and aetiology of 94 patients who were identified as PID according to the latest IUIS classification at our immunology/allergy clinic during a period of 21 years.5 These patients were referred to Amir-kola Pediatrics hospital, the main referral hospital in Babol, Mazandaran province. Mazandaran is a northern state in Iran with a population of 3,074,000 located to the south of the Caspian Sea, indicating a PID prevalence of 30.5 per 1,000,000 populations. This is significantly higher compared to overall prevalence of PID in Iran which was estimated to be 9.7 per 1,000,000 population during the years 2006 to 2013.18

The major aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of various types of PID in the North of Iran and provide local demographic information. It should be emphasised that the result of the current report does not necessarily reflect the true prevalence of PID, which may be due to lack of awareness among physicians and inadequate available diagnostic capabilities. In severe cases of PID such as SCID, many patients die in their early childhood before the exact diagnosis is made and their cause of death remains unknown.9,19 In addition, patients with mild forms of the disorder are usually managed by general physicians or other specialists and are not referred to any tertiary centres.20–22 Early diagnosis and management of PID has a crucial role in diminishing the rate of morbidity and mortality, and increasing the quality of life in PID patients.18,23,24

The overwhelming majority of our PID cases were diagnosed in children (93.2%), which was higher than previous reports from Iran. This contrast in age range among our PID patients with other reports may be due to our lower patient population study and also a poor referral system for adult patients (20).

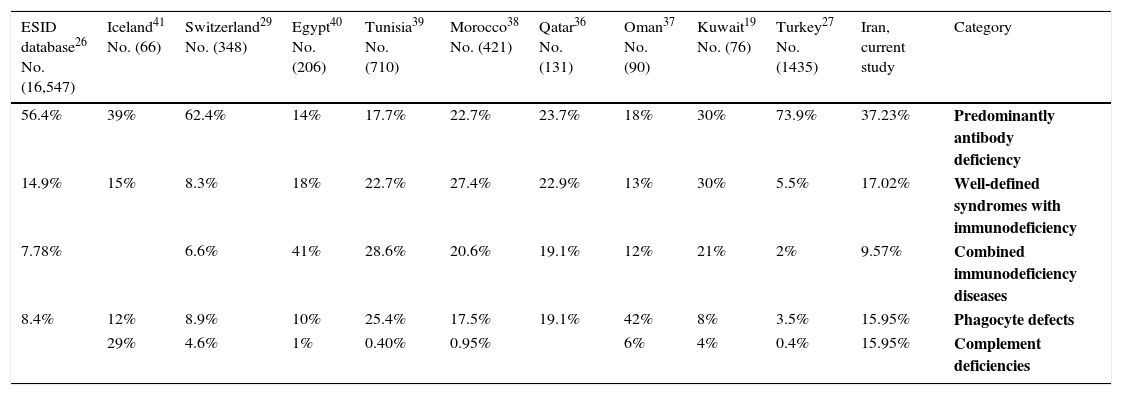

As shown in Table 3, the spectrum of PID observed in the present study was similar to previous studies.6,25–30 Patients with antibody deficiency were identified in 65% of the PID population. This is consistent with prior international reports including data from Europe (54.82%), Turkey (74%), Australia (71%), Korea (53.3%), Japan (52.9%), and Switzerland (66.2%).27,29–32 Among patients with antibody deficiency, our results indicated CVID to be the most prevalent disorder followed by IgA deficiency and XLA. These findings are in concordance with the study carried out by the Iranian Primary Immunodeficiency Registry (IPIDR), indicating CVID to be the most prevalent antibody disorder in the country.9 While many other registries have shown IgA deficiency to be the most common phenotype of PID, we could only identify 10 patients (10.63%) in our cohort with IgA deficiency.33,34 This discrepancy in low incidence of IgA deficiency among our patients’ population may be resulting from asymptomatic presentation of IgA deficiency in most of the cases, leading to a lower rate of diagnosis for this type of PID.9

Distribution of some PID subtypes in different countries.

| ESID database26 No. (16,547) | Iceland41 No. (66) | Switzerland29 No. (348) | Egypt40 No. (206) | Tunisia39 No. (710) | Morocco38 No. (421) | Qatar36 No. (131) | Oman37 No. (90) | Kuwait19 No. (76) | Turkey27 No. (1435) | Iran, current study | Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 56.4% | 39% | 62.4% | 14% | 17.7% | 22.7% | 23.7% | 18% | 30% | 73.9% | 37.23% | Predominantly antibody deficiency |

| 14.9% | 15% | 8.3% | 18% | 22.7% | 27.4% | 22.9% | 13% | 30% | 5.5% | 17.02% | Well-defined syndromes with immunodeficiency |

| 7.78% | 6.6% | 41% | 28.6% | 20.6% | 19.1% | 12% | 21% | 2% | 9.57% | Combined immunodeficiency diseases | |

| 8.4% | 12% | 8.9% | 10% | 25.4% | 17.5% | 19.1% | 42% | 8% | 3.5% | 15.95% | Phagocyte defects |

| 29% | 4.6% | 1% | 0.40% | 0.95% | 6% | 4% | 0.4% | 15.95% | Complement deficiencies |

In the present study, phagocytic disorders comprised 15.95% of our PID populations with CGD being the most common form (8.51%), which was shown to be similar to results from Latin American countries and Japan (8.6% and 11.9%, respectively), but significantly higher than European studies.26,32,33

In patients with autosomal recessive disorders, such as Chediak-Higashi syndrome, Griscelli syndrome, CGD and severe congenital neutropenia (SCN), consanguinity marriages seem to be a major risk factor.16,35 The overall average of the consanguinity rate found in our study was 24.7%, which is higher than in other studies, but still lower than the overall consanguinity rate of the country's population (38.6%).16 The consanguinity rate among our patients diagnosed with immune dysregulation was 100%, which is higher in comparison with other reports such as in Europe and other Asian countries which have been shown to have lower rates of consanguinity marriages.6,26,28

The present study is the first report of PID in Northern Iran. Variations in frequency of different types of PID exist in different regions of Iran. Therefore, collecting local data can be used to improve the local health care system strategists and quality of care of patients diagnosed with PID.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.