Asticot maggot (Blowfly, Calliphoridae family) is the most important live bait used for angling in our country. Prevalence of allergy to live fish bait in occupationally exposed workers has been described. The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of asticot allergy in amateur fishermen and the identification of marketed asticot species in Cáceres, Spain.

Materials and MethodsSeventy-two randomised selected patients (Angler's Society of Cáceres) completed a questionnaire about fishing habits and allergic symptoms related with live bait handling. Skin prick test (SPT) with local asticot and common earthworm extracts were performed. Serum IgE levels to imported species (Protophormia terraenovae, Calliphora vomitoria, Lucilia sericata, Lumbricus terrestris) were measured. Local asticot and common earthworm samples were obtained for taxonomic identification. Data were analysed using the SPSS 12.0 software.

ResultsFive patients (7 %) reported allergic symptoms caused by asticot maggots. All of them were positive for SPT to asticot and specific IgE to P. terraenovae. Sensitisation to P. terraenovae was found in 40 patients (58.8 %). No associated factors for asticot allergy were observed. Larvae and adult flies of local asticot samples were identified as P. terraenovae.

ConclusionsCommercially available asticot, in Cáceres, is composed by P. terraenovae larvae (Diptera. Calliphoridae). A 7 % prevalence of P. terraenovae allergy in amateur fishermen of Cáceres was obtained. The allergenic potential of P. terraenovae seems to be greater than that of other blowflies and L. terrestris. The SPT with P. terraenovae extract is a very sensitive and specific technique in the diagnosis of live bait allergy in fishermen.

Freshwater sport fishing is one of the most popular pastimes in Cáceres, Spain. The asticot is the most commonly used live bait in the area, having replaced more traditional baits, such as the earthworm, thanks to its great avidity for all types of fish. The name “asticot” is used by French companies to sell fly larvae from the Calliphoridae family as live fishing bait. Within the asticot range, there are various fly species that are practically indistinguishable as larvae. There are over 1000 Calliphoridae species in existence worldwide, with less than 50 known species in Spain. P. terraenovae (of the Calliphoridae family) is a species that prefers low temperatures for its offspring and is capable of surviving extreme climatic conditions. This explains its abundance, especially in cold regions and in the higher-altitude areas of milder regions. In Spain, only a few wild P. terraenovae specimens have been proven to exist in the Aragonese Pyrenees1.

In 1982, Stockley et al2 described the first case of hypersensitivity to fly larva of the Calliphoridae family in a fisherman with contact urticaria and late asthmatic responses related to the use of this bait. Since then, in most of the cases described of allergic reactions to fly larvae in exposed fishermen or workers, the species involved primarily pertain to the Calliphora spp and Lucilia spp genera (Calliphoridae family). The studies conducted by Siracusa et al. demonstrate the allergenic importance of Lucilia caesar3 and Calliphora vomitoria4 in comparison with other live bait. There are no published cases of allergies to P. terraenovae in international literature, except for one case described in a Spanish communication5.

Considering how often live bait is used and its ability to provoke allergic reactions, there is a lack of studies which assess the allergenic potential of this live bait in fishing enthusiasts. Therefore, we present a descriptive study on allergic reactions caused by fishing bait in a group of fishermen in Cáceres. The objectives of this study are to identify the bait involved, the frequency of the presentation of allergic reactions to them, and to analyse the possible risk factors for their development.

The difficulties in diagnosing the allergic pathology caused by this bait are primarily based in the problems of selecting and identifying the raw materials and in the lack of biologically standardised extracts. The aim of this study is to carry out a taxonomic identification of the dipteran sold as asticot in the fishing equipment stores in Cáceres. In this way, specific extracts can be made of the specific species to which the fishermen of our region are exposed.

Materials and MethodsTaxonomic IdentificationVarious samples of asticot and common earthworms were gathered from three fishing equipment stores in the city of Cáceres. Imported samples (Verminiere de L'ouest. Tremblay, France) were also obtained from the asticot range, sold and labelled with the following taxonomic identification: “l'asticot (P. terraenovae)”, “le gozzer (C. vomitoria)” and “le pinkie (L. caesar)”, as well as L. terrestris (common earthworm). Once these samples were collected, they were sent to the Parasitology Unit of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Extremadura, for their taxonomic identification. Fifty third-instar larvae were analysed from each of the samples. A first provisional classification was established by following the guidelines of Smith (1986)6. In order to ensure that the dipteran species were correctly identified, their biological cycle was completely carried out until adult flies were obtained. These were then classified following the guidelines of González-Mora & Peris 1 , González-Mora7, and Peris & González-Mora8.

Diagnostic extractsLocal and commercially available asticot and common earthworm species were extracted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) 50 % w/v at 4–8 °C. After it had been stirred for 2 h (1000 rpm), the solution was centrifuged at 10.000 g for 30 min. The resulting supernatant was then passed through Watman filters. This filtration was dialyzed in a dialysis membrane (Visking 7000 Da) for 12 hours at 4 °C. The extract resulting from the dialysis was then filtered in a vacuum through filters with a Millipore GS depth of 0.45 ^m. It was then frozen at —20 °C in order to undergo a lyophilisation process. The protein concentration of the final extract was determined by Bradford assay as previously described9. The extracts were reconstituted at a 5 mg/ml concentration at the moment of their use for in vivo and in vitro tests.

Subjects and diagnostic proceduresThe study was presented to the Ethics Committee of the hospital Complejo Hospitalario de Cáceres with a favourable outcome. Seventy-two randomly-selected patients (members of the Cáceres Fishing Association) agreed to participate in the study. All the patients filled in a questionnaire based on the ECRHS10 and ISAAC11 epidemiological questionnaires with a series of modifications that included questions regarding fishing habits and the possible presence of symptoms (skin, nasal, ocular, respiratory) related to the use of live bait. That same day, blood samples were taken in order to obtain the serum that was frozen at —20 °C until its use in the specific IgE determinations. After the samples were taken, skin prick tests (SPT) were carried out with the asticot and local earthworm extracts in all the patients. SPT were performed with the allergy pricker lancet (Dome-Hollister-Stier) as described elsewhere12. Histamine phosphate (10 mg/ml) served as positive control and NaCl (0.9 %) as negative control. The tests were read after 20 minutes. A reaction was considered to be positive if the wheal size was at least 3 mm diameter larger than negative control. Ten atopic and ten non-atopic controls were tested for SPT. All the patients underwent a prick test with a battery of conventional inhalant allergens (Laboratorios Diater, Spain). Atopics were defined as having a positive clinical history and a SPT reaction more than 3 mm to at least one common allergen.

Specific IgE levels to imported samples of asticot and L. terrestris, as determined by ELISA method, were measured at the end of patient recruitment. Briefly, protein extracts (250 μg/ml) were bound to 96-well polystyrene microplates (Costar, Cambridge, Mass.) by overnight incubation at 4 °C. After washing with PBS-0.1 % Tween, plates were neutralised with 1 % bovine serum albumin (1 hour at room temperature), washed, and incubated with undiluted serum samples (2 hours at room temperature). The union of the IgE was detected by a biotinylated human anti-IgE monoclonal antibody (1:1000; 50 μL/well; Operon, Spain) followed by an incubation with a mouse anti-IgE antibody marked with streptavidin-peroxidase. After a final washing, a substrate solution was added and the colour was allowed to develop. The enzymatic reaction was stopped with HCl, and the absorbance values were measured at 450 nm. The observed absorbance data was transferred to a master curve obtained with the use of reference sera, following WHO specifications (IRP2 75/502). In this study, the specific IgE levels > 0.7 UI/ml were considered positive against the corresponding allergen in order to avoid false positive results.

Statistical analysisData were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SSPS, version 12.0). The x2 and the M2 tests were used to analyse significant differences (P < 0.05) between allergic, asymptomatic sensitised patients, and normal subjects.

ResultsFollowing the anatomical analysis of the local asticot samples (both of the third-instar larvae and the emerging imagos), it was observed that 100 % of the individuals belonged to the Protophormia terraenovae species. The P. terraenovae larvae measure up to 17 mm in length. They have a last segment with very pointed tubercles and posterior spiracles with a faint peritremal button. The adult flies measured 6-11mm and were of a dark metallic blue colour, wing scale with hairs on their posterior half and bare thoracic scale. The analyses of the imported asticot samples confirmed the identification of Protophormia terraenovae (l'asticot) and Calliphora vomitoria (le gozzer). In the case of “le pinkie”, the analysed larvae were identified as L. sericata instead of Lucilia caesar. Contamination with other species was not observed in any of the samples.

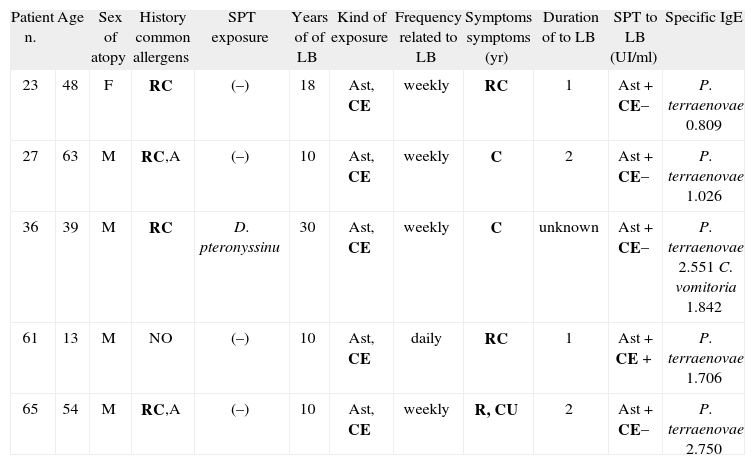

Of the 72 patients analysed, 65 were men (90.3 %) and 7 were women (9.7 %). The average age was 43 (6–80 years old, standard deviation of 19 years). Ninety-four per cent of the patients used asticot as their main bait. Ninety per cent of the patients also claimed they used earthworms, although only occasionally. The amount of time they spent practicing their hobby was generally limited to weekends (56 % of patients), during the spring and summer months (68 %). A total of 42 % of the fishermen and women (30 individuals) presented respiratory symptoms (rhinitis and/or asthma). Twenty-two (31 %) were atopic. Five patients (7 %) related their symptoms to the handling of asticot. The most common symptom was conjunctivitis in the form of pruritus, conjunctival hyperaemia and watery eyes in four patients. Three patients presented symptoms of rhinitis and one patient, contact urticaria. No patients developed bronchial asthma symptoms. The symptoms are of a one or two-year evolution and appeared after having used this type of bait for 10 years or more. Table I shows the characteristics and results of the immunological study conducted on these five patients.

Clinical data and immunological study of symptomatic patients.

| Patient n. | Age | Sex of atopy | History common allergens | SPT exposure | Years of of LB | Kind of exposure | Frequency related to LB | Symptoms symptoms (yr) | Duration of to LB | SPT to LB (UI/ml) | Specific IgE |

| 23 | 48 | F | RC | (–) | 18 | Ast, CE | weekly | RC | 1 | Ast+ CE– | P. terraenovae 0.809 |

| 27 | 63 | M | RC,A | (–) | 10 | Ast, CE | weekly | C | 2 | Ast+ CE– | P. terraenovae 1.026 |

| 36 | 39 | M | RC | D. pteronyssinu | 30 | Ast, CE | weekly | C | unknown | Ast+ CE– | P. terraenovae 2.551 C. vomitoria 1.842 |

| 61 | 13 | M | NO | (–) | 10 | Ast, CE | daily | RC | 1 | Ast+ CE + | P. terraenovae 1.706 |

| 65 | 54 | M | RC,A | (–) | 10 | Ast, CE | weekly | R, CU | 2 | Ast+ CE– | P. terraenovae 2.750 |

RC: Rhinoconjunctivititis; A: asthma; CU: Contact urticaria; Ast: asticot; CE: common earthworm; LB: live bait.

All the patients with a positive clinical history of allergy to fishing bait had a positive skin test with the asticot (P. terraenovae) extract. Eight patients showed positive skin tests with the asticot extract (11.1 %) and four patients, with the earthworm extract (5.5 %). Two of the patients had a positive response with both extracts. Of the eight patients with a positive skin test with asticot, five presented symptoms related to the use of this bait, and another three were asymptomatic sensitised. Non-exposed controls gave negative results for asticot and common earthworm extracts.

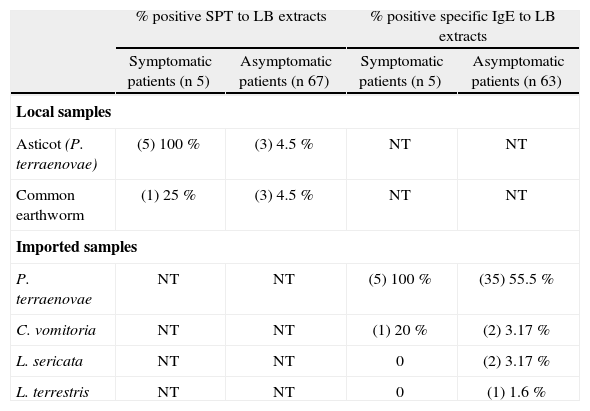

A total of 68 sera (five patients did not give consent) were analysed for specific IgE determinations with the P. terraenovae, C. vomitoria, L. sericata and L. terrestris extracts. P. terraenovae was practically the only species capable of inducing sensitisation, with evidence of specific IgE antibodies in 40 of the analysed sera (58.8 %). Only three positive responses to C. vomitoria were obtained, two with L. sericata (patients who also responded to P. terraenovae) and one with L. terrestris. There were only two patients (no. 51 and 52) with specific IgE with the three blowfly species and none of them reacted to L. terrestris. A very large percentage of the in vitro sensitisations with P. terraenovae was obtained in asymptomatic patients (55.5 % of asymptomatic sensitisations). Only one patient of the five with positive clinical history presented positive specific IgE with C. vomitoria and none with L. sericata and L. terrestris. The tests conducted in healthy patients not exposed to fishing bait were negative.

Table II features a summary of the results of the immunological study in the 72 patients.

Summary of the immunologic data in the 72 fishermen

| % positive SPT to LB extracts | % positive specific IgE to LB extracts | |||

| Symptomatic patients (n 5) | Asymptomatic patients (n 67) | Symptomatic patients (n 5) | Asymptomatic patients (n 63) | |

| Local samples | ||||

| Asticot (P. terraenovae) | (5) 100 % | (3) 4.5 % | NT | NT |

| Common earthworm | (1) 25 % | (3) 4.5 % | NT | NT |

| Imported samples | ||||

| P. terraenovae | NT | NT | (5) 100 % | (35) 55.5 % |

| C. vomitoria | NT | NT | (1) 20 % | (2) 3.17 % |

| L. sericata | NT | NT | 0 | (2) 3.17 % |

| L. terrestris | NT | NT | 0 | (1) 1.6 % |

LB: Live bait; SPT: skin prick test; NT: not tested.

No risk factor was observed for the development of allergy to asticot.

DiscussionThe present study has allowed us to learn about fishing habits in Cáceres, the bait involved in the allergic reactions, as well as the frequency and way in which these reactions present themselves amongst our fishermen.

In our study, with 72 patients who practiced the hobby of fishing, and at highly-varied levels of exposure to bait, 7 % of patients5 experienced symptoms related to the use of asticot (P. terraenovae). None of these patients associated their symptoms with the use of earthworms. It is a percentage of patients similar to the 9.2 % obtained by Siracusa et al. in the studies on the prevalence of occupational allergy to live bait 4, and less than the 28 % obtained in the study by Kaufman et al13 conducted on highly-qualified patients from an entomological research centre exposed to Lucilia cuprina. In these cases, the workers were exposed to a production of thousands of litres of bait in airtight rooms or spaces for five hours or more a day. Thus, the intensity of the exposure was not comparable to that of the fishermen who limited their sport activity to weekends during the spring and summer months in the outdoors. The most common clinical manifestation of the allergy to P. terraenovae was the immediate appearance of rhinoconjunctivitis symptoms at the beginning of a fishing day. We did not have any patients with asthma symptoms, probably due to the small number of symptomatic patients and the short evolution time of the symptoms, between 1 and 2 years. The authors of the Kaufman study13 observed that the rhinitis symptoms tended to precede the beginning of the asthma symptoms. Thus, it is not surprising that, in a subsequent follow-up, the allergic fishermen began to present bronchial asthma symptoms if they continued to be exposed to this bait.

The skin test with P. terraenovae turned out to be a very sensitive technique, since all the tests on the symptomatic patients were positive (100 % sensitivity). The specificity dropped a little, to 95.5 %, due to the existence of three false positives. This diagnostic yield is higher than that obtained by Siracusa et al4 with C. vomitoria extracts.

The sensitivity of the specific IgE determination with P. terraenovae using the ELISA technique was 100 %, but in this case, at the expense of a very high percentage of false positives and as a result, of a very low specificity, 44.5 %. This lack of specificity is comparable to the results obtained by Kaufman's group13 in which sensitisations to L. cuprina in asymptomatic patients was up to 33 %. The scarcity of response with the C. vomitoria and L. sericata extracts in symptomatic patients makes it possible to conclude its lack of validity for the in vitro diagnostic in this population.

Considering the set of results from the clinical questionnaires, skin tests and specific IgE measurements, there was a 7 % frequency of fishermen allergic to P. terraenovae. In the Siracusa study4, only two (2.6 %) cases of patients allergic to C. vomitoria (despite being the most commonly used bait) were observed. In the Kaufman study13, of 28 % of initial patients with allergic symptoms in relation to L. cuprina, an IgE mechanism could only be confirmed in 10 patients, 18 % of the total. Thus, we are within the ranges of prevalence of allergic reactions due to blowflies described by those authors. P. terraenovae, sold as live bait for sport fishing (asticot), acts as a new aeroallergen, with the ability to produce respiratory allergy pathology in 7 % of those who practice fishing in Cáceres. The allergenic potential of P. terraenovae seems to be greater than that of other blowflies, as it is able to produce reactions with a minimum level of exposure.

In an attempt to obtain information regarding exposure intensity, the patients were classified by those exposed on a daily, weekly, monthly and yearly basis. Taking into account the limitation of this classification, not having estimated the time of daily exposure (as it is variable, due to being a pastime and not subject to a set work schedule), there were no significant differences in any of the groups with regard to the development of allergy to the live bait. Nor did atopy appear as a risk factor for the development of sensitisation or allergy to asticot or earthworm. The type of bait used could not be analysed as a risk factor, since the majority of the patients stated that they used various types, primarily asticot and earthworm (although the latter was used much less). In short, risk factors could not be established for the development of allergy to the bait studied, which is in line with the observations of the previous studies4,13.

The lack of identification of the exposure source and of the raw materials used to create the diagnostic extracts presents a two-fold problem that could result in errors in the allergenic importance of some live bait. The sensitivity results of the specific IgE determinations with the C. vomitoria and L. sericata extracts in the population studied, are an example of the increase in false negatives that we could have obtained if a good selection and identification of the allergenic source to which the patients were exposed, had not been made. Various authors refer to the flesh fly larvae14,15, to asticot16,17, or to a complete genus2,18, without identifying the specific fly species. Other authors identify “bluebottle” with the Calliphora vomitoria species18,19 and “greenbottle” with the Lucilia caesar species3,20. The characteristic of the colour green, for example, could be applied to the entire Lucilia spp genus, but is not exclusive to this genus. Furthermore, the differences between one species and another, within the same genus, such as between L. sericata and L. caesar, for example, can vary only in the colour of the basicosta (second smooth scale located at the wing base). On the other hand, the information provided by the companies that dedicate themselves to breeding this type of bait could be incorrect. The experiences obtained in this study are an example. The producer of the asticot sold in Cáceres had no record of the species it was producing. Furthermore, the analysis of the imported asticot samples confirmed an error in the labelling, since the L. caesar species was really L. sericata, which reaffirmed our initial suspicion.

The analysis of asticot sold in Cáceres showed that our fishermen are exposed to P. terraenovae, an imported blowfly species that is not a regular part of our region's indigenous entomofauna and which has begun to produce allergic reactions in the fishermen.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.