Specific immunotherapy (SIT) is at present the only causal treatment for allergic disorders. Successful SIT is capable of inducing a physiological immune tolerance towards the causal allergen. The mechanism of action is still not completely known, however a restoring of T regulatory cells and a T helper 1 repolarisation are associated with clinical improvement after SIT.1

Many double-blind placebo-controlled trials and meta-analysis studies evidenced that SIT is effective and safe, and indications and contraindication are well defined.2 However, SIT efficacy is a matter of debate as it does not work in all allergic patients. In fact, there is at present no predictive biomarker capable of predicting the clinical response to SIT.

On the other hand, in clinical practice there is indication for SIT in patients with well-documented IgE-dependent symptoms3. Allergen-specific IgE may be detected in vivo (by skin prick test) or in vitro (by quantitative assay).

Previously, some cytokines were associated with successful SIT (including IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, IFN-γ, TGF-β), but their measurement in clinical practice is not available and recommended.4 A recent study reported that the calculation of the serum specific-IgE/total-IgE ratio may predict the clinical response to SIT in monosensitised patients to grass, Parietaria judaica, Olea europea, and house dust mites.5 However, this study was conducted in a particularly selected cohort of monosensitised patients and total IgE were assessed. The real life practice suggests that most allergic patients are polysensitised and total IgE may be in the normal range, also in atopic patients.

Therefore, we performed a real life study enrolling candidate patients to SIT. The aim was to investigate whether serum specific-IgE could be associated with effective SIT.

Seventy-five patients (40 females; median age: 35 years) suffered from allergic rhinitis. Blood sampling for assessing serum specific-IgE (sIgE) was performed in all subjects before initiating SIT. Serum levels of specific-IgE were measured by the IFMA procedure (ImmunoCAP Thermo Fisher Scientific). Quantitative specific IgE concentrations were expressed in kU/L according to the traceable calibration to the 2nd IRP WHO for Human IgE. Specific IgE levels were considered positive over 0.35kU/L.

Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical software package Medcalc 9 (Frank Schoonjans, BE). Medians (md) and percentiles (25th and 75th, IQR) were used as descriptive statistics. The non-parametric Wilcoxon's test was used to compare samples. In addition, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed in order to determine a cut-off for sIgE that could optimise the sensitivity and the specificity of the test, to identify responder subjects. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Most patients (62; 86.7%) were polysensitised, but a single extract was prescribed in all subjects. All patients assumed sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT): 56 were allergic to pollens (37 to grass, 11 to ragweed, eight to birch), 19 to perennial allergens (11 to house dust mites, four to dog, four to moulds). SLIT was administered for three years: by a preseasonal course (four months) for pollen extracts, continuous for perennial allergens. Phleum pratense, Betula alba, and Ambrosia extracts were manufactured by Stallergenes Italy; Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus extract was manufactured by Lofarma; dog and Alternaria tenuis extracts were produced by Alk-Abellò.

The SIT effectiveness was calculated considering both clinical improvement and drug use (prescribed on demand) reduction. Patients globally evaluated both parameters, reporting their perception by the visual analogue scale (VAS). Responder patient was defined on the basis of a VAS reduction of at least 30% compared with the baseline VAS (such as before starting SLIT).

After three year SLIT, 63 patients (84%) were responders: 34 (92%) to grass, seven (87%) to birch, seven (64%) to ragweed, nine (82%) to mites, four (100%) to dog, and two (50%) to moulds. On the contrary, 12 patients (16%) were non-responders.

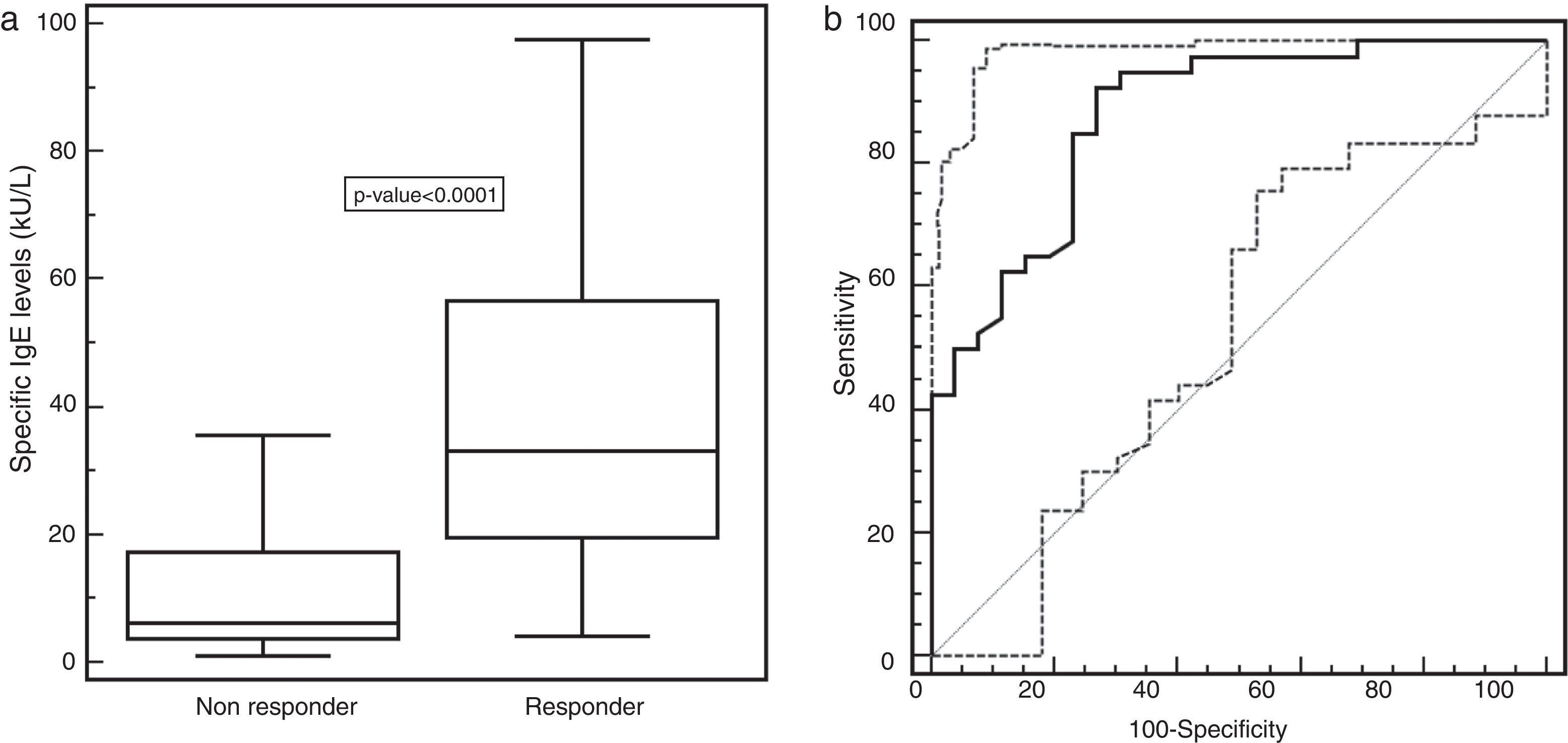

Serum specific-IgE levels were significantly higher (p-value <0.0001) in responder patients (med: 33.15kU/L; 25–75th: 19.65–56.65kU/L) than in non-responder ones (med: 6.12kU/L; 25–75th: 3.69–17.2kU/L), as shown in Fig. 1a. The ROC analysis showed that a specific-IgE concentration more than 14.3kU/L was the optimal cut-off to discriminate between responder and non-responder patients. The associated sensitivity and specificity were 92.5% (95% CI 79.6–98.3) and 73.1% (95% CI 52.2–88.4), respectively. The positive and negative predictive values were 84.1% and 86.4%. The corresponding area under the ROC curve of 0.879 (95% CI 0.775–0.946) indicated a good discriminating capability (Fig. 1b).

(a) Specific IgE distribution (kU/L) in SLIT-treated patients, evaluating responders and non-responders separately. Values were represented as medians (black line), quartiles (25th and 75th percentiles, white box), and p-value between the groups. (b) ROC curve of the chosen cut-off of 14.3kU/L for the specific-IgE levels in responder or non-responder patients.

This preliminary study demonstrated that serum specific-IgE measurement before starting SLIT might be useful for individuating responder patients. In fact, a value >14.3kU/L was a reliable cut-off for discriminating responder patients. The availability of a biomarker predicting the SIT outcome would be extremely useful in the clinical practice, but it should be reliable and easily achievable. Serum specific-IgE assay is a popular test, commonly used by the allergist. Moreover, IgE positivity is a typical marker for the allergic phenotype and serum specific-IgE levels are associated with symptom severity.6 This study, conducted on a real life basis, confirmed the previous study based on monosensitised patients, but it should be followed by trials conducted on larger cohorts to confirm these findings.

In conclusion, serum specific-IgE might be considered a biomarker for indicating the SIT responsiveness.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human subjects and animalsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestAll authors declare that they have no conflict of interest concerning the present study.