Asthma exacerbation is an episode of (sub)acute worsening of asthmatic symptoms. Exacerbation may depend on environmental factors.

ObjectiveThe present study investigated emergency calls for asthma exacerbation in children, analysing: i) their trend over the course of time; and ii) their possible relationship with environmental factors, including pollen count, meteorological parameters, and air pollution.

MethodsEmergency calls for exacerbation were recorded for 10 years (from 2002 to 2011) in Genoa (Italy). Betulaceae, Urticaceae, Gramineae, and Oleaceae pollen counts were measured. Meteorological parameters and air pollutants were also measured in the same area and for the same period.

ResultsThe number of emergency calls did not significantly modify during the time studied. Two main peaks were detected: during the autumn and the spring. Wind speed significantly diminished as did most air pollutants. There were significant and relevant relationships between emergency calls and: pollens during the spring (r=0.498), rainfall (r=0.818), wind speed (r=0.727), and air pollutants (r=0.622 for SO2; r=0.699 for NO; r=0.58 for NO2).

ConclusionsThis 10-year survey demonstrates that: (i) asthma exacerbations did not diminish over the time; (ii) there were seasonal peaks (autumn and spring); (iii) pollens (mainly Parietaria), wind speed and rainfall, SO2, NO, O3 and NO2 were strongly associated with asthma exacerbations in children in this area. Therefore, asthma exacerbations may significantly depend on environmental variations.

Despite advances in asthma management, asthma exacerbations continue to occur and the frequency varies depending on the severity and the degree of control.1 The most comprehensive data on exacerbation incidence derive from therapeutic clinical trials: asthmatics receiving optimum treatment should only have one exacerbation every three years.2 However, these clinical trials do not reflect the real exacerbation rates, as they are conducted in optimal conditions both for patients’ characteristics and methodology. For example, a survey analysing reports of US emergency departments demonstrated that 73% of patients had had at least one visit for asthma exacerbation in the previous year.3

Asthma is the most common chronic disease among children.4 Its prevalence is up to 10% of the general paediatric population in Europe.5 Asthma is a public health problem that is under-diagnosed and under-treated. It causes a substantial burden to children and their families and often restricts children's activities and school performance. In addition, having an asthma exacerbation is one of the most distressing events in childhood asthma.6 Asthma exacerbation is an episode of (sub)acute worsening of asthmatic symptoms.7 The majority of asthma exacerbations are usually preceded by viral upper airway infections.8 Other exacerbation triggers are also: allergen exposure, weather conditions, and air pollutants.9 However, an accepted and univocal definition of asthma exacerbation is still debated. Two types of definition have been proposed: conceptual (precise descriptions of the meaning of a word) and operational (describing the presence or quantity of defined objects by derivable properties). The common denominator is a deterioration of symptoms, and three different ways to define an exacerbation can be considered: increased symptom severity, fall in lung function parameters, and healthcare utilisation.7 To propose asthma definition, assessment, and standardisation, National Institutes of Health and federal agencies recently convened an expert group.10 The proposed definition of asthma exacerbation is a worsening of asthma requiring the use of systemic corticosteroids to prevent a serious outcome.10 Healthcare utilisation represents a relevant component in exacerbation outcomes.

Recently, a study has been carried out in order to evaluate the medical emergency calls requiring attention for asthma exacerbations among the population of the territory of Genoa (Italy) in an eight-year period.11 This survey reported that the frequency of asthma exacerbations in children did not diminish over time. More recently, the collection of pollen counts, weather and pollutants records concerning the last 30 years in the same city was analysed.12 This study provided evidence that some sensitisation significantly increased, pollen counts exerted a higher pressure, and climate and pollution changed, very probably influencing pollen release. On the other hand, there is no study on this issue that has been conducted for a long period.

For these reasons, the present study aimed at evaluating the trend of medical emergency calls for asthma exacerbations in children, also collecting pollen count, weather, and air pollutants records during the period 2002–2011 in the Genoa (Italy) area. The purposes were: (i) to evaluate the time trend, and (ii) to detect a possible relationship among the clinical phenomena, such as asthma exacerbations, pollen count, meteorological data, and air pollution.

Materials and methodsThe territory of Genoa has a population of about one million of inhabitants. Genoa is a port city situated on the Mediterranean Sea (20m above sea level, latitude 44°25′N and longitude 8°56′E), is in the north-west of Italy, and has a temperate climate.

Clinical dataThe clinical data were provided by the records of the 118 Medical Emergency Control Center of Genoa, in its capacity as a body officially coordinating all medical emergencies by telephone. The medical staff code all incoming calls as per the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9). The San Martino Hospital's Ethics Committee has approved this study procedure. The data were analysed both considering the years and months of incidence, in children (0–17 years) and were regularly recorded between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2011.

Pollen dataAerobiological data regarding pollination period were assessed, and pollen concentrations recorded in the same period. The monitoring of pollens was performed at the survey centre of San Martino Hospital concerning the first two decades, then data were collected by ARPAL (Agenzia Regionale per la Protezione dell’Ambiente Ligure), according to standard methods of the Italian Aerobiology Association (AIA), now also recognised as: UNI 11108. Airborne pollens were collected using a Burkard seven-day-recording volumetric spore trap, standard equipment used for aerobiological sampling worldwide. This spore trap was placed 20m above ground level and away from sources of pollution. The choice of pollen species was based upon two criteria: (i) they had to be the most important pollen types causing sensitisations and allergic symptoms in the people living in this geographic area; and (ii) they had to be present in the atmosphere, every year, in relatively high or significant concentrations. For these reasons, four pollen species were measured: Gramineae, Betulaceae, Urticaceae, and Oleaceae.

Gramineae included Phleum p, Dactylis g, Poa a, Lolium s, and Festuca e. Betulaceae included Betula alba, Alnus, and Corylaceae (such as Corylus a. and Carpinus a.) were added. Urticaceae included Parietaria judaica and Parietaria officinalis. Oleaceae included olive tree.

For each taxon, 52 mean weekly pollen concentration values and peaks (grains/m3 air) were recorded and the sum of 52 weekly pollen concentration values gave an estimate of the annual amount of each pollen species. These four major allergenic species (Betulaceae, Gramineae, Oleaceae and Urticaceae) were regularly recorded between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2011.

Meteorological dataMeteorological data included the yearly average values for temperature (°C), rainfall (mm), relative humidity (%), dew point (°C), visibility distance (km), and wind speed (km/h). All the data were collected and managed by “Il Meteo srl” (provided by the Air Force Observatory of Genoa). The data were regularly recorded between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2011.

Air pollution dataAir pollution data included the yearly (from 2002 to 2011) average values for carbon monoxide CO (μg/m3), sulphur dioxide SO2 (μg/m3), nitrogen oxide NO (μg/m3), nitrogen dioxide NO2 (μg/m3), ozone O3 (μg/m3), and PM10 (μg/m3). All the data were collected and managed by the Environment and Territory Department of the “Provincia di Genova” (Observatory of Genoa). The data were regularly recorded between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2011.

Statistical analysisCorrelation between quantitative variables was evaluated by means of the Spearman's correlation coefficient (r). Regression was used to describe trend of variables during the years. The association between total pollen count and pollen season, meteorological and air pollution data was also estimated by multiple regression analysis in order to find multiple independent predictors of the count. All tests were two sided and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The software Medcalc 9 (Frank Schoonjans, Belgium) was used for all analyses.

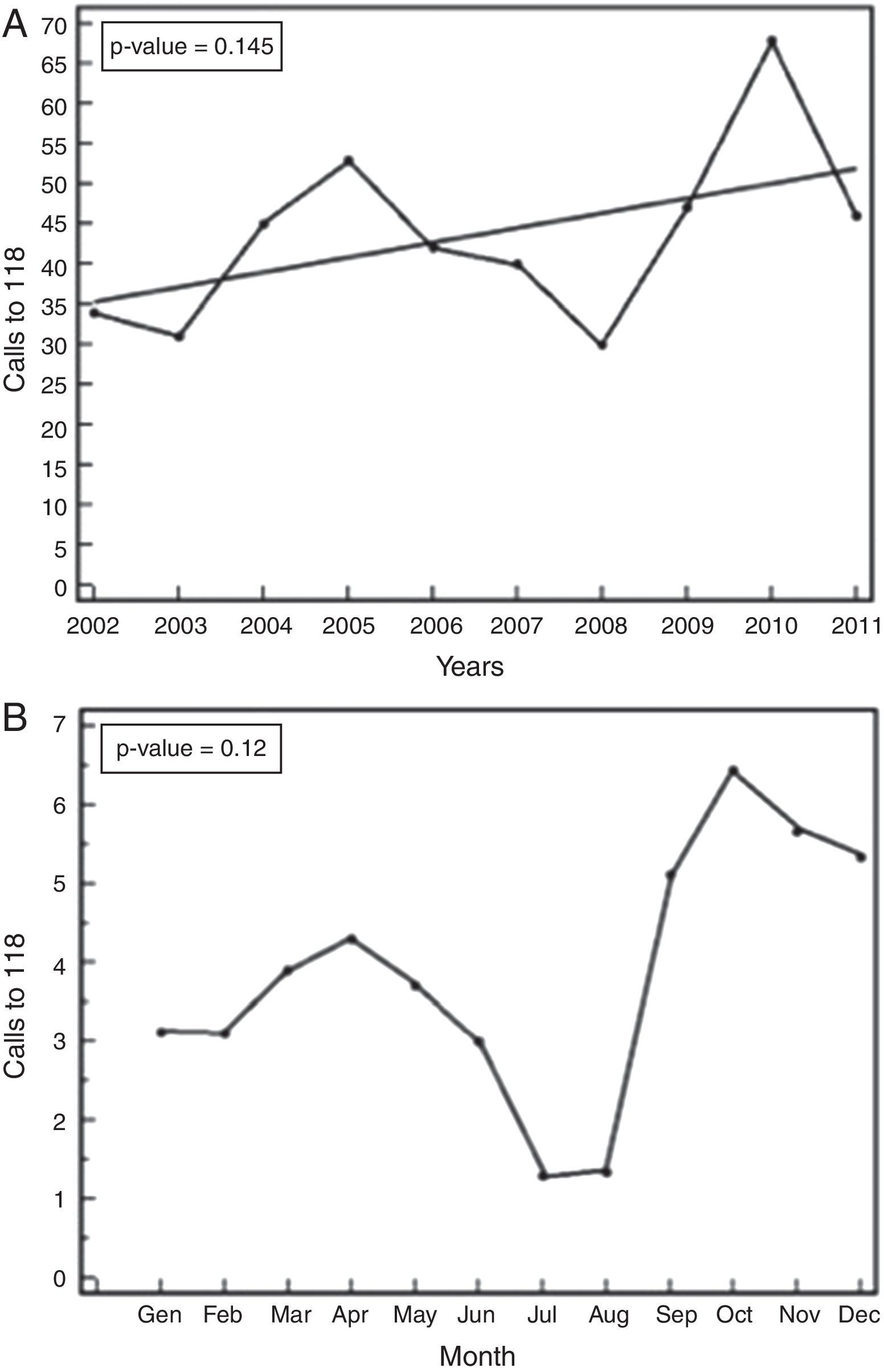

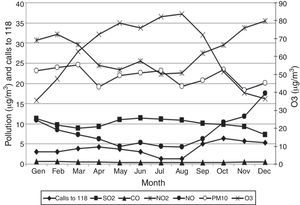

ResultsClinical dataFirstly, an increasing trend of emergency calls has been observed during the 10 years under consideration, although it is not statistically significant (Fig. 1A). The analysis of data concerning the gender of children shows that there was no statistically significant difference between males and females. Secondly, the analysis of the emergency calls per month shows that there was a significant (p-value <0.0001) periodic temporal trend of the calls and there were two peaks: the main one being in the autumn and the second during the spring, without difference between genders (Fig. 1B).

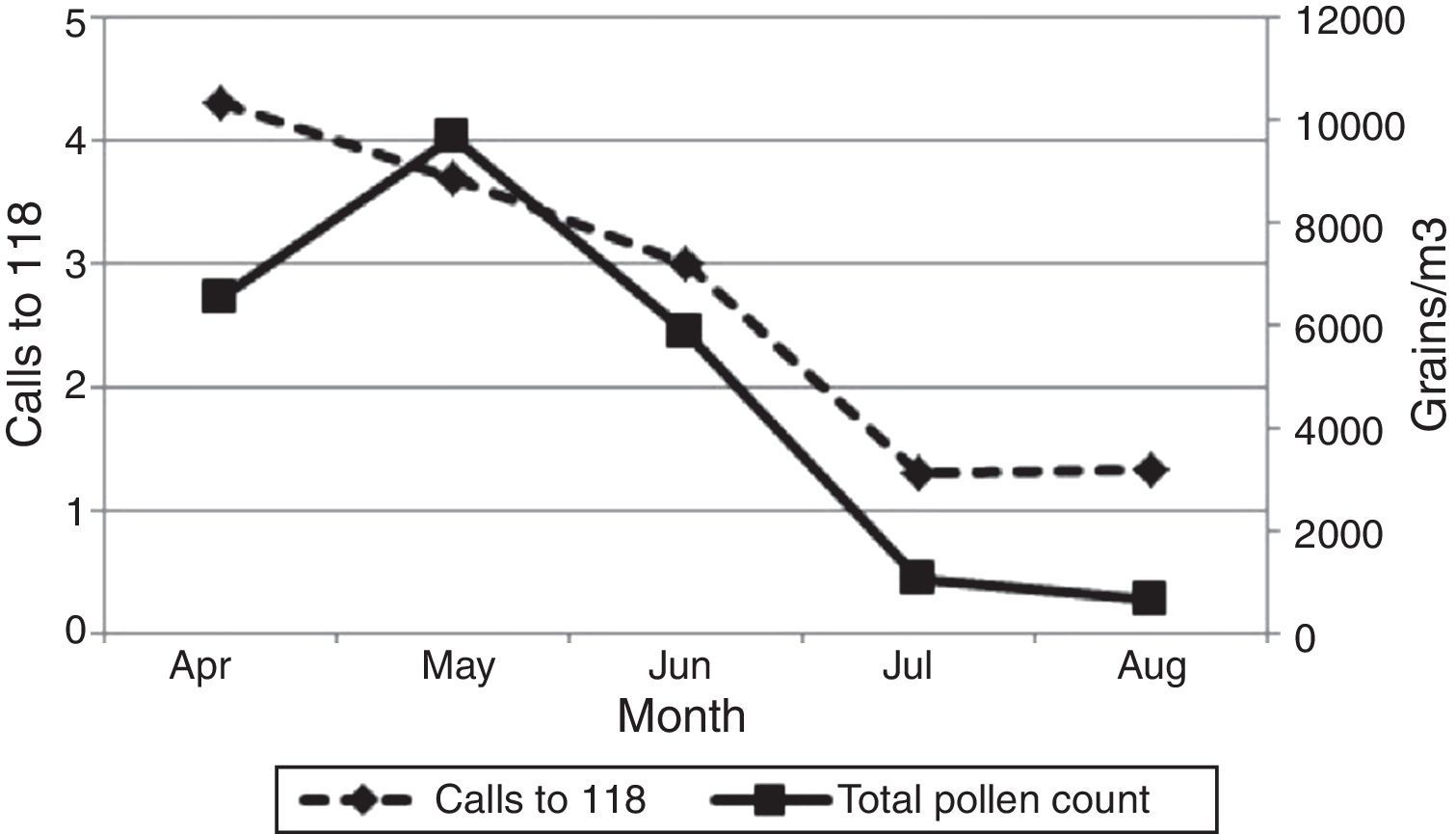

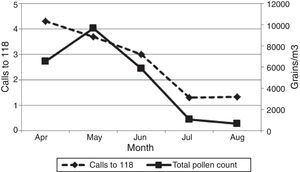

Pollen countPollen counts trended to increase across the years for Oleaceae, Gramineae and Urticaceae, but not significantly, instead Betulaceae pollens trended to decrease across the years, but not significantly (data not shown). Moreover, we observed a significant periodic temporal trend of the Betulaceae pollen count (p-value <0.0001), Gramineae (p-value <0.0001), Oleaceae (p-value <0.0001) and Urticaceae (p-value <0.0001). More interestingly, there was a significant and positive correlation (p-value <0.001, rho=0.498) between emergency calls and total pollen count, from April to August. Fig. 2 presents the temporal trend of calls and total pollen count in these months.

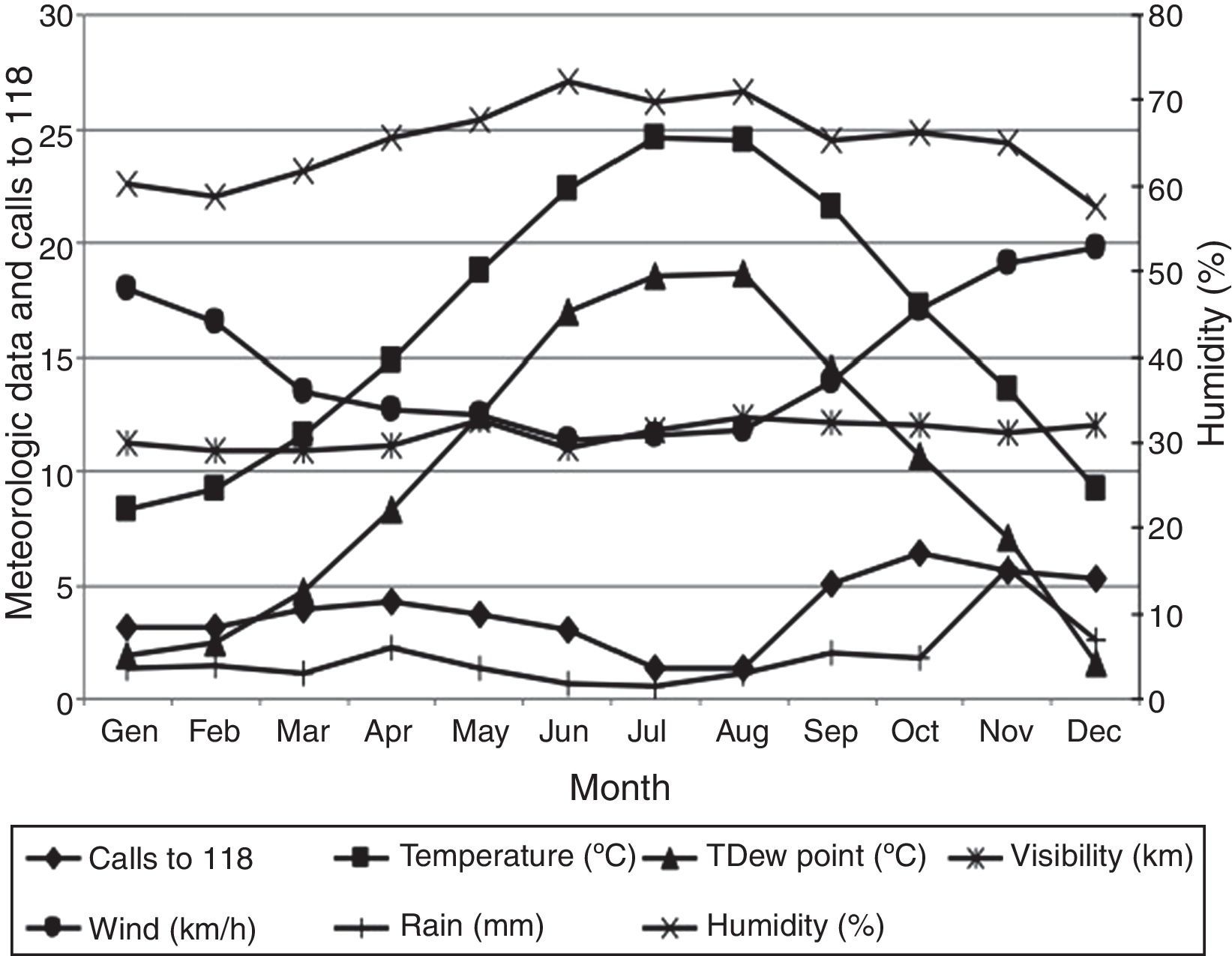

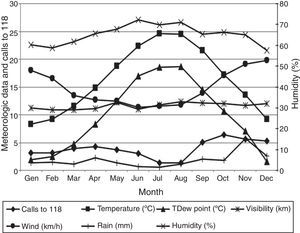

Meteorological dataAcross the years, wind speed significantly decreased (p-value <0.01) during the years. No significant temporal trends were observed for the other meteorological data. Moreover, we observed significant parabolic trends over months for dew point (p-value <0.001), temperature (p-value <0.001), humidity (p-value <0.01) and wind speed (p-value <0.001). There was a positive and strong correlation between wind speed and emergency calls (p-value=0.02, rho=0.727), and a positive and very strong correlation between rainfall and calls (p-value <0.01, rho=0.818). In addition, there were negative significant correlations between emergency calls and temperature (p-value <0.01, rho=0.35), dew point (p-value <0.01, rho=0.26), and humidity (p-value=0.02, rho=0.31). Emergency calls were plotted against meteorological data (Fig. 3).

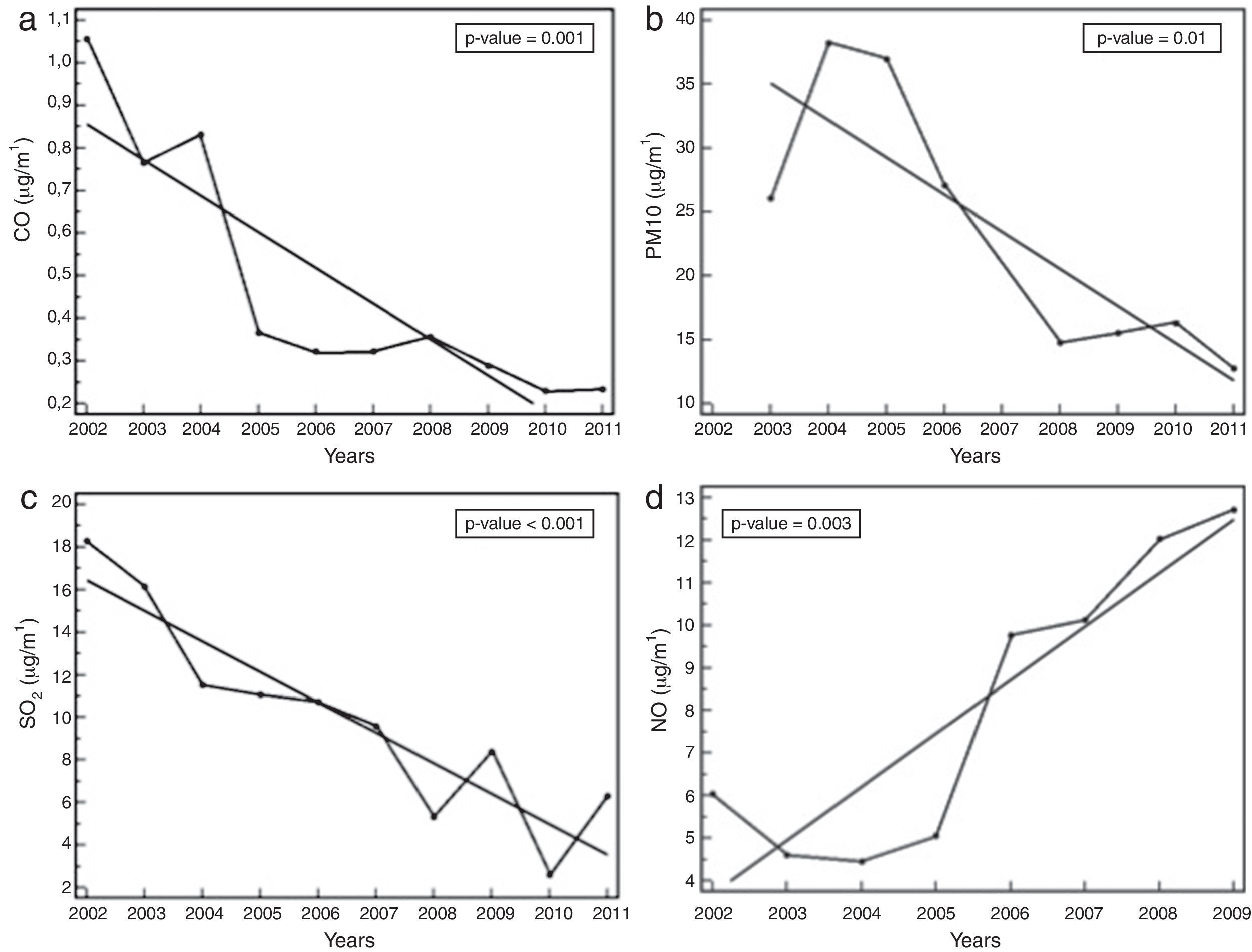

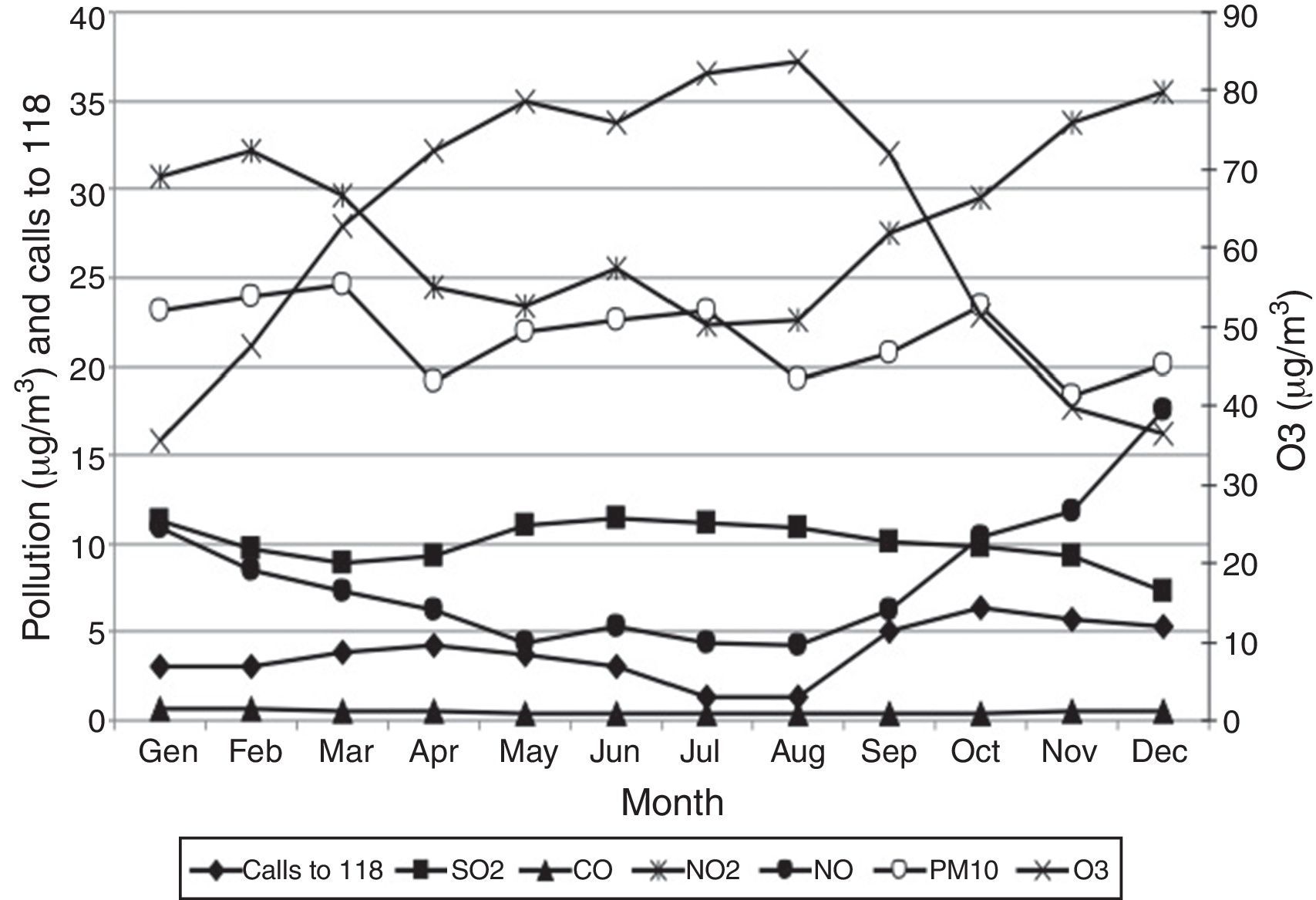

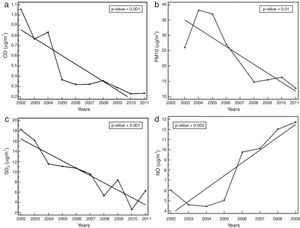

Air pollution dataCO levels (p<0.01, Fig. 4a), PM10 levels (p=0.01, Fig. 4b) and SO2 levels (p<0.001, Fig. 4c) significantly decreased, whereas NO levels significantly increased (p<0.01, Fig. 4d). Moreover, we observed significant parabolic trends over months for CO (p-value <0.001), NO (p-value <0.001), NO2 (p-value <0.001) and O3 (p-value <0.001). There were positive and strong correlations between SO2 and emergency calls (p-value=0.04, rho=0.622) and between NO and calls (p-value=0.02, rho=0.699). In addition, there was a positive and moderate relationship between NO2 and emergency calls (p-value=0.05, rho=0.58). Emergency calls to 118 were plotted against air pollution data (Fig. 5).

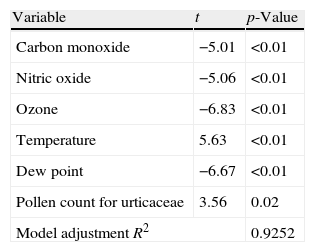

The number of emergency calls per month was significantly correlated with NO, O3, CO, dew point, temperature and pollen count for Urticaceae and the best (p<0.01) multivariate model combined these variables (Table 1).

DiscussionThe analysis of children with uncontrolled asthma who called the emergency home service suggests some clinically relevant considerations. Although asthma guidelines have been widely spread to both specialists and family paediatricians, it is clear that the number of asthma exacerbations did not diminish during the years considered. This study was designed to investigate the possible relationships between these environmental agents and asthma exacerbations assessed by emergency calls in a 10-year period.

Unfortunately, the number of emergency calls does not diminish over the 10-year period; rather there was an increasing trend. This finding must induce a serious remark on the global management in children with asthma.

Analysing the yearly distribution, two main peaks are evident: the most relevant during the autumn, and the second during the spring. The autumn peak may be most likely due to two main causes: respiratory infections and house dust mite exposure. Both factors are more prevalent during the autumn. However, this study did not assess these two issues.

With regard to the pollen count, there was a trend of variation over the study period, but it was not significant. On the other hand, the assessment of the seasonal occurrence of pollens is more relevant. Typically, all pollen species peaked during the spring, with an overlapping among species between April and May. Interestingly, there was a significant and direct relationship between the global quantity of all pollens and emergency calls during the warm months. This finding underlines and confirms the causal role of allergen exposure in inducing asthma exacerbations in children.

In relation to meteorological parameters, the only significant variation over the study period was the wind speed that diminished. This finding might exert a pathogenic role as the wind constitutes a relevant factor able to affect the presence of air pollutants. On the other hand, there were significant seasonal variations concerning the meteorological variables: typically there were the peaks of humidity and temperature during the summer associated with a nadir for the wind speed. From a clinical point of view, some seasonal variations correlated with emergency calls. Particularly, the wind speed was strongly and positively related with emergency calls. In other words, the more intense the wind was, the more numerous the emergency calls were. The relationship between rainfall quantity and emergency calls was stronger. These data might represent a practical application: when there is hard rain and the wind blows intensively, it is reasonable to expect several emergency calls for asthma exacerbations.

About air pollution data, most pollutants significantly diminished over the time, except NO. This finding reflects the effect produced by rigorous restrictions on pollutant emission, even though the efforts were not sufficient to also reduce NO. Anyway, significant seasonal variations were evident during the year: all pollutants, but no ozone, peaked during the cool seasons, mainly depending on home heating and congested traffic. The impact of pollution variations on emergency calls was particularly evident. In fact, SO2, NO, and NO2 were significantly and directly associated with emergency calls. This finding confirms and highlights the relevant role exerted by air pollution on respiratory symptoms in childhood, mainly concerning asthma exacerbations. Unexpectedly, there was a negative relationship between ozone levels and emergency calls. Probably, this finding could be explained by the reduction of all the other causing factors, such as pollens, meteorological parameters, and other air pollutants.

Finally, the regression model showed that there was a significant correlation among several environmental factors. Parietaria pollens were the most relevant, as were dew point, temperature, and air pollution.

Therefore, this study demonstrates that asthma exacerbations in children may be significantly dependent on environment, even though probably there is globally no single sufficient factor.

The topic concerning the causal factors of asthma exacerbations is still debated, but is object of several studies. In this regard, a recent review pointed out that although considerable progress has been made, much remains to be done.13 Current evidence clearly provides the suggestion that every effort has to be made to obtain optimal treatment to achieve adequate control of asthma. This goal means to significantly affect the risk of severe asthma exacerbations. In fact, poor control can lead to asthma exacerbation.14 In fact, children with persistent asthma and at least one severe exacerbation in the previous year have a two-fold increased risk of subsequent severe exacerbations.15 Other risk factors for asthma exacerbations are: viral infections16; allergen exposure17; younger age18; season15; environmental tobacco smoke exposure19; and outdoor air pollution.20

A recent study outlined that asthma exacerbations are probably associated with allergens or irritants, supporting the relevance of atopy in children with severe asthma.21 More recently, it has been reported that the association between aeroallergen exposure and hospitalisation for asthma has enhanced on days of higher pollution.22 However, also long-term exposure to pollutants is associated with uncontrolled asthma, defined by symptoms, exacerbations, and lung function.23 In fact, air pollution may also significantly affect lung function over time.24

Considering all these aspects, the present study confirms the relevance of allergens, weather, and air pollution as factors associated with asthma exacerbations in children. The present study differs from previous ones as it included all the above-mentioned parameters together and overall it considered a long period of observation, such 10 years.

However, this study has some limitations: house dust mite levels were not measured nor were viral respiratory infections considered, as there is no epidemiological report concerning this issue. In addition, there was unfortunately no data concerning visits to the emergency department, family doctor practice or ambulance intervention.

In conclusion, this 10-year survey demonstrates that: (i) asthma exacerbations did not diminish over the time; (ii) there were seasonal peaks (autumn and spring); and (iii) pollens (mainly Parietaria), wind speed and rainfall, SO2, NO, O3 and NO2 were strongly associated with asthma exacerbations in children.

Conflict of interestAll authors declare that they contributed to the study and have no conflict of interest concerning the present study.

Ethical disclosuresPatients’ data protectionConfidentiality of data. The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentRight to privacy and informed consent. The authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchProtection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

We would like to thank Dr Molina of the Arpal, Dr Brescianini of the Provincia of Genoa, and Dr DeAmici and Giunta of the IRCCS-San Matteo Hospital of Pavia for their helpful contribution.