To the Editor:

The number of known animal food allergens is limited. Although chicken meat is quite a common part of European diet and hen's egg is one of he most frequent allergens in children, severe poultry meat allergy without sensitisation to egg proteins is extremely rare.1–3 Allergy to turkey and duck meat is even more rarely reported and the implicated allergens are poorly characterised.2–4 In the bird-egg syndrome, sensitisation to chicken feather allergen occurs by the respiratory route and afterwards allergy symptoms appear due to bird meat consumption. The implicated allergen is thought to be alpha-livetin.2 We report a clinical case of severe chicken and turkey meat allergy without sensitisation to egg proteins. There was also coexisting Leguminosae allergy.

The particular interest of this case is the need for liver transplantation and use of immunosuppressive therapy in the patient with familial amyloid neuropathy.

Solid organ transplantation with the use of calcineurine inhibitors, especially tacrolimus, is a risk factor for new food allergies and probably for aggravation of the pre-existing food allergy.5 For this reason, careful elimination diet and immunosuppression with alternative drugs are very important in the post-operative period.

A 31-year-old Caucasian man, with a diagnosis of familial amyloid neuropathy, proposed for liver transplantation, was referred to our Immunoallergology Department for investigation of food allergy.

At the age of 21 and 23, he experienced generalised pruriginous erythema, laryngeal tightness and sialorrhoea immediately after ingestion of cooked red beans, white beans and black-eyed beans. At the age of 29, the patient developed generalised itch, palmar erythema, laryngeal tightness and dysphagia after ingestion of grilled chicken meat. One year later, he had a similar episode with ingestion of grilled turkey meat and oropharyngeal pruritus and sialorrhoea with ingestion of duck meat.

Following that, the patient eliminated all poultry meat and every type of beans from his diet. He had never had any complaints after ingestion of other legumes (namely soy), tree nuts and cooked or fresh eggs and had not previously ingested goose, pheasant and/or grouse meat.

The patient had symptoms of recurrent nasal obstruction from the age of 20 without seasonal aggravation. There was no contact with birds in the domestic environment and no history of eczema, asthma or drug allergies.

Skin prick tests (SPT) were performed with plastic Morrow-Brown needle (Stallerpoint®, Stallargenes) with extracts of the most common inhalant allergens and commercially available extracts of food allergens in a 0.5 % phenolated solution and 50 % glycerine (Bial-Aristegui®, Bilbao, Spain). Saline was used as a negative control and 10mg/mL histamine phosphate as a positive control.

The SPT results were evaluated after fifteen minutes and reactions were considered positive if the largest wheal diameter was 3mm over the negative control.

Cooked and raw chicken, turkey and duck meat, cooked and raw red and black-eyed beans were tested by prick-toprick tests.

Serum total and specific IgE were determined by enzyme-immunoassay following the manufacturer's instructions (UniCAP®, Phadia, Uppsala, Sweden). Inhibition study was performed using RAST technique (UniCAP®, Phadia, Uppsala, Sweden) and results were expressed as percentage inhibition. Sodium dodecylsulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) Immunoblotting was carried out according to the method of Laemmli.6

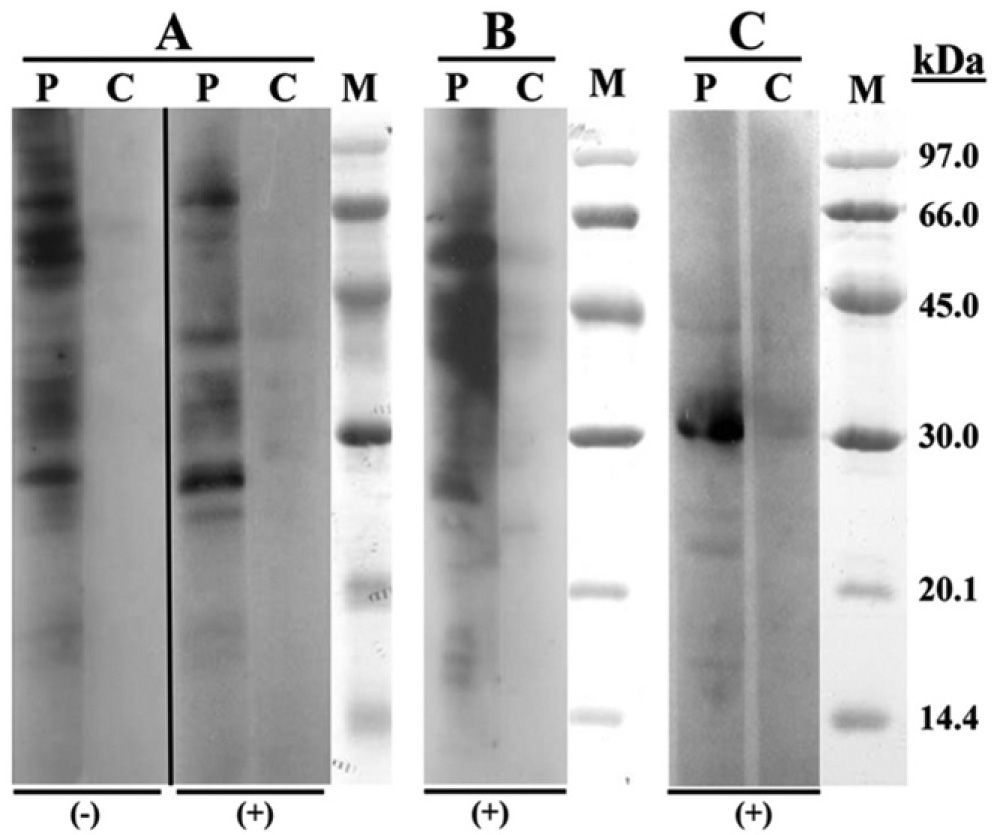

Skin and serological test results are shown in Table I.

Skin and serological test results

| Commercial allergens | SPT, mm | sIgE, kU/L | Commercial allergens | SPT, mm | sIgE, kU/L |

| Negative control | 0 | – | Plantago lanceolatum | 5.5 | 0.73 |

| Positive control | 5.5 | – | Artemisia | 6.0 | 0.32 |

| Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus | 8.5 | 3.1 | Parietaria judaica | 0 | NP |

| Dermatophagoides farinae | 7.5 | 2.0 | Latex | 0 | NP |

| Acarus siro | 0 | NP | Feathers mix | 0 | 0 |

| Blomia tropicalis | 0 | NP | Egg white | 0 | 0 |

| Euroglyphus maynei | 0 | NP | Egg yolk | 0 | 0 |

| Lepidogyphus destructor | 0 | NP | Ovomucoid | 0 | 0 |

| Alternaria alternata | 0 | NP | Ovalbumin | 0 | 0 |

| Asperillus fumigatus | 0 | NP | Lentil | 0 | 0 |

| Cladosporium | 0 | NP | Chickpea | 7.0 | 0.31 |

| Mucor | 0 | NP | Pea | 6.0 | 0.24 |

| Penicillium | 0 | NP | Peanut | 0 | NP |

| Candida albicans | 0 | NP | Soybean | 0 | NP |

| Trichophyton rubrum | 0 | NP | Broad bean | 0 | NP |

| Grass pollen mix | 6.5 | Green bean | 0 | NP | |

| Lolium perenne | 7.5 | 3.52 | White bean | 5.5 | 0.20 |

| Phleum pratense | 6.5 | 3.2 | Chicken meat | 6.0 | 0.43 |

| Olea europea | 7.5 | 0.84 | Turkey meat | 0 | 0.14 |

| Betula | 0 | NP | Duck meat | 0 | 0 |

| Native food | PPT, mm | Native food | PPT, mm |

| Chicken meat (cooked) | 9.5 | Duck meat (cooked) | 0 |

| Chicken meat (raw) | 8.0 | Red bean (raw) | 0 |

| Turkey meat (raw) | 9.5 | Red bean (cooked) | 0 |

| Turkey meat (cooked) | 9.0 | Black-eyed bean (raw) | 0 |

| Duck meat (raw) | 0 | Black-eyed bean (cooked) | 0 |

SPT: Skin Prick Test, mean diameter of the wheal; sIgE, serum specific IgE; NP: not performed; PPT: prick-to-prick test, mean.

Food challenge was not performed due to the underlying disease and because of the clear clinical data with reproducible symptoms.

RAST inhibition study between rye-grass pollen and bean was positive (91 %); the inverse study was negative.

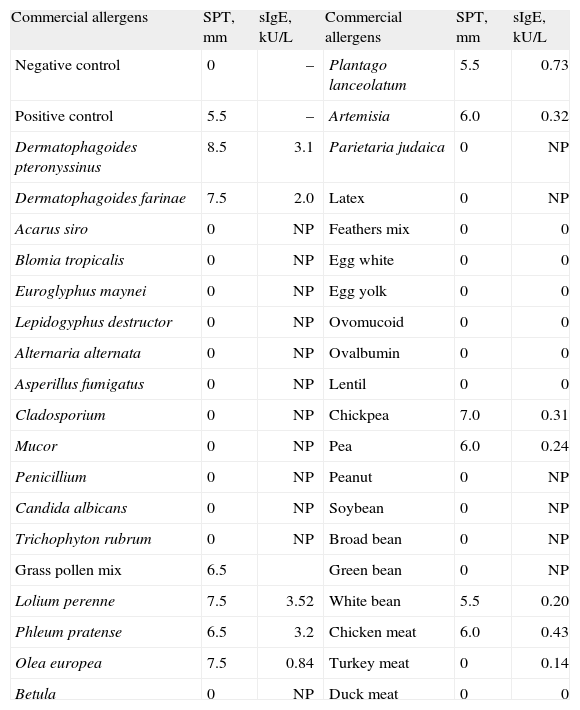

SDS-PAGE Immunoblotting (Fig. 1) showed IgE binding bands of 27, 42 and 70kDa in both, chicken and turkey raw meat extracts. Regarding turkey meat there was an intense fixation band in the 55kDa region. The assay with bean extract demonstrated binding bands of 31kDa.

The patient was instructed about the elimination diet (avoidance of all avian meat, beans, pea and chickpea) and the use of intramuscular adrenaline Kit. He was submitted to a liver transplantation with a use of cyclosporine as immunosuppressive drug without any complications during one year of follow-up.

Patients with so-called “bird-egg” syndrome exhibit cutaneous and respiratory symptoms after ingestion of egg-yolk and/ or inhalation of feathers. In the majority of cases the allergen involved is alpha-livetin (chicken serum albumin) and sensitisation occurs by respiratory route.2 Allergy to poultry meat is rare and the implicated proteins are poorly characterised.

We describe a rare case of severe chicken and turkey meat allergy and oral allergy syndrome after ingestion of duck meat. The patient had no sensitisation to egg proteins. IgE-mediated mechanism was confirmed by skin prick, prick-to-prick tests and serum specific IgE measurements.

According to the published results, patients with bird-egg syndrome have specific IgE antibodies against a 70-kDa protein of egg yolk, whereas those who suffer from chicken meat allergy but no feathers or egg allergy show IgE antibodies against several lower molecular weight proteins of chicken meat.3,4 Our IgE-Immunoblotting study revealed proteins of 27 and 42kDa with both chicken and turkey meat2–4. A protein of 55kDa was only found with the turkey meat extract, a protein with a similar molecular mass was previously reported by Cahen et al.2 Although IgE binding has been described at 70kDa-band in studies with both chicken and turkey meat extracts, this binding was weaker than with sera from patients with bird-egg syndrome.4

The results of electrophoresis of various avian meats performed by Kelso et al. showed that duck meat has binding bands (8kDa, 16kDa) different from chicken, turkey and goose meat. This fact can probably explain milder symptoms of our patient in exposure to duck meat with negative skin prick-to-prick test results and negative specific IgE measurement.

Legumes are dicotyledonous plants belonging to the Fabales order. This botanical order is formed by three families: Mimosaceae, Caesalpiniaceae and Papilionaceae. Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), chickpea (Cicer arietinum) and pea (Pisum sativum) belong to the Papilionaceae family.7 Our patient had anaphylaxis after ingestion of red, white, and black-eyed bean, positive tests with pea and chickpea commercial extracts and elevated specific IgE to chickpea.

According to previously published results in Mediterranean population, about 80 % of patients allergic to legumes had sensitisation to pollen; pea and bean were the legumes with more in vitro cross reactivity with Lolium perenne.7

Our RAST inhibition studies with rye-grass pollen and bean extracts showed the existence of cross-reactivity between both allergenic sources and the initial respiratory sensitisation to grass pollen. In the report of Ibanez et al., there was cross-reactivity between pea (Pisum sativum) and bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) in about 23 % of the patients studied.7

To our knowledge, there are no reports of cross-reactivity between bean and chickpea (Cicer arietinum). SDS-PAGE Immunoblotting performed with bean extract revealed implicated protein of 31kDa. The protein with similar molecular weight (30kDa) was previously described for soy (Glycine max).8

Our patient had no complaints with soy ingestion and had negative skin and serological test results for soy.

The cross-reactive allergens of Leguminosae family are poorly characterised and the risk of cross-reactivity is hard to predict, in any case elimination diet is recommended only for foods with positive clinical data or oral provocation tests. We suggested elimination of beans because of clear clinical data and laboratory results. Pea and chickpea elimination was suggested because of sensitisation, documented by skin prick-to-prick tests in the patient with elevated food allergy risk.

When a patient has allergy to hen's meat without sensitization to hen's egg, the risk of cross-reactivity with other types of poultry meat is increased3. This fact was the reason for a very restrictive diet with elimination of all poultry meat.

It is well recognized that immediate-type hypersensitivity and life threatening food allergy may arise post-liver transplantation in patients treated with tacrolimus and it has been suggested that those at greater risk are patients with a personal history of atopy5. The mechanism of this phenomenon is poorly understood. Tacrolimus increases intestinal permeability and probably also antigen transport across gastrointestinal epithelium. Besides, as other calcineurin inhibitors, tacrolimus was associated with suppression of interleukin-2 and interferon-gamma, having no effect on IL-4 and IL-10 (Th2 cytokines). Cyclosporin is significantly less potent than tacrolimus, so the current recommendations for cases with high risk of food allergy after solid organ transplantation involve dietary manipulations – elimination diet and replacement of tacrolimus by cyclosporine5. In this particular case we suggested cyclosporine therapy and a rigorous elimination diet with avoidance of all poultry meat and Leguminosae. The patient had no complications and has been asymptomatic during one year of follow-up.

We describe a rare case of an adult with allergic rhinitis who had serious allergic reactions to various beans and poultry (chicken and turkey). The complexity was increased due to the need for immune suppression for liver transplantation.