To evaluate the impact of parental education on the success of Asthma Educational Intervention (AEI).

MethodsAEI took place after the children's hospitalisation. Parental asthma knowledge was assessed at three time points: before AEI, immediately after, and 12 months later. The Intervention (I) group of parents (N=231) received complete AEI. The Control (C) group of parents (N=71) received instructions for proper use of asthma medications and the handbook.

ResultsAsthma knowledge in I group increased immediately after the AEI (p<0.01), and had not changed (p>0.05) 12 months later. There were four subgroups in group I divided based on education level: elementary school, high school, college, and university degrees. Taking into account the parental education level, there were no differences in the baseline and final knowledge of asthma between subgroups (p>0.05). The number of asthma exacerbations decreased after AEI (5.96:2.50, p<0.01), regardless of the parental degree. Knowledge of asthma in group C did not improve during the study (p=0.17). Final asthma knowledge was higher in group I compared to group C (p<0.01).

ConclusionThe parental education level did not influence the level of asthma knowledge after the AEI. The motivation and the type of asthma education had the greatest input on the final results.

Practice implicationsAll parents should be educated about asthma regardless of their general education.

As in every chronic disease, the education of parents and patients about all aspects of childhood asthma is very important. The education of patients is recognised as the fundamental basis for childhood asthma monitoring, symptom control, and treatment.1 The education of parents improves morbidity,2,3 knowledge, compliance, self-management efficiency,4,5 the control of asthma, and quality of life.6–8 There are many factors related to the characteristics of the disease in children such as society, parents, family and a method of asthma education. All can have an impact on the patient and parental asthma knowledge.

Guidelines on the management of asthma promote asthma education as one of the strongest keys to improving asthma exacerbations.9–12 Regardless of high public awareness of asthma and allergies during the past years, the evidence suggests that the knowledge of asthma is still low.13,14 On a daily basis, we face the denying of the disease, unsatisfactory asthma prevention and control and behavioural problems in children and parents.15,16 The majority of developed countries have widely introduced asthma self-management through their national health programmes. Updated guidelines issued by the National Asthma Education and Prevention Programme (NAEPP) outlined essential components of asthma therapy, symptom monitoring, patient education and trigger avoidance in asthma.11 However, in undeveloped countries as well as in transitional countries, there is the medical and economic burden of uncontrolled asthma.17,18 In Serbia, we introduced Asthma Educational Intervention (AEI) in our hospitals, endorsed by the ERS Educational Grant, as a part of the Asthma action plan in 2004. This was the first structured one-year follow-up survey of research in asthma education and its impact on children's asthma outcomes in Serbia. The main goal of AEI was to educate parents to have a better understanding of numerous aspects of childhood asthma including diagnosis, prognosis, management, and treatment perceptions among the patients with asthma. The impact of parental education on improvement of children's asthma outcomes, symptom perception, usage of medications and self-management evaluation, and the impact of environmental tobacco exposure to children with asthma were reported elsewhere.19,20

The aim of our study was to analyse parents’ knowledge of asthma before and after the AEI, and its influence to baseline and final, acquired knowledge of asthma as well as the success of AEI. Our hypothesis was that the higher the level of parental education, the higher their baseline and final acquired asthma knowledge.

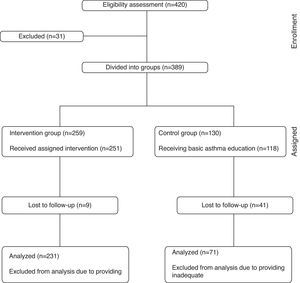

MethodsParticipantsThe study included parents of 420 children (aged 7–16 years) hospitalised for acute asthma exacerbation that required IV/IM corticosteroid therapy at least three days in the Children's Hospital for Respiratory Diseases and Tuberculosis. Study data were collected from June 2005 till June 2006 and analysed in 2007. Only children living with both parents participated in the study. Neither the actual child preventive medication nor Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA)9 categorisation into moderate/severe persistent asthma groups was not considered within the inclusion criteria. We excluded 31 parents whose children did not meet the inclusion criteria: 21 children had an additional chronic illness and 10 parents changed their mind and refused to take part in the study.

InterventionUnequal randomisation with a ratio 2:1 was used as ethically feasible. We considered the usefulness of complete AEI in real life situations, and the number of parents with complete AEI was intentionally doubled. The randomisation procedure did not depend on sex and age of children, or on age of parents.

Both parents of 259 children were randomly assigned to the Interventional (I) group, while both parents of 130 children were randomly assigned to the Control (C) group. Group I received the complete AEI. The complete AEI consisted of five movies and audio-visual Power Point presentations related to all aspects of asthma and the proper use of asthma medications, the handbook entitled “Meet your asthma” and workshop/panel discussions which followed afterwards. Group C received only the instructions for the proper use of asthma medications and the handbook.

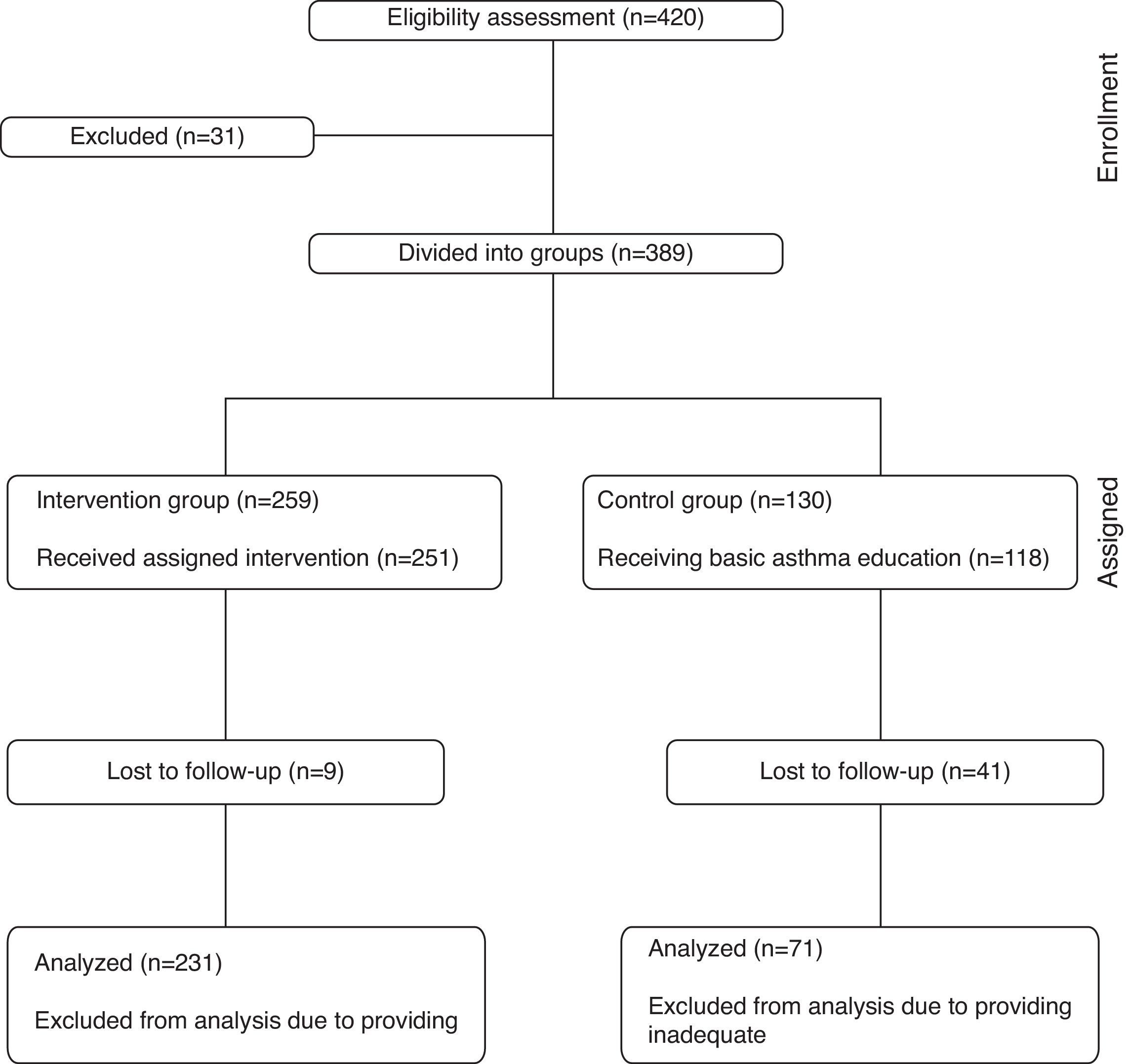

The parents of eight children were excluded from group I because their children were briefly hospitalised and they had no time to complete the education, or they were not able to attend the lectures on the appointed days because of living too far away. Both parents of 251 children received the complete AEI. Immediately after the education, the handbook titled “Meet your asthma”,21 with a written Asthma Action Plan (AAP) was provided to them. Due to relocation to another city or lost telephone contact, the parents of nine children were lost to follow-up. Interrupted interventions occurred in five cases and because of this they missed their regular appointments. Additionally, the parents of six children were excluded because they provided inadequate written answers in the questionnaire, and so the data of the parents of 231 children were finally analysed (Fig. 1).

In group C, the parents of 12 children did not receive the basic education because parents intentionally shortened the hospitalisation of a child. The rest of the parents of 118 children were instructed about the proper medication inhaler technique when their children were discharged from the hospital and they were given the handbook with the AAP. The parents of 41 children were lost to follow-up (they were relocated to another city or lost a telephone contact). The parents of six children were excluded from further analysis because they provided inadequate written answers in the questionnaire, and so the data of the parents of 71 children were finally analysed (Fig. 1).

The children of parents participating in both groups had regular check-ups every four months. In the case of an emergency, there was a possibility for unscheduled visits.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the institution, and consent of patients and parents was obtained.

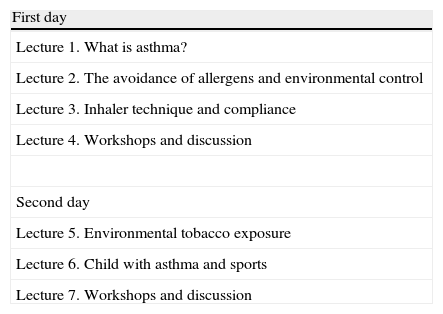

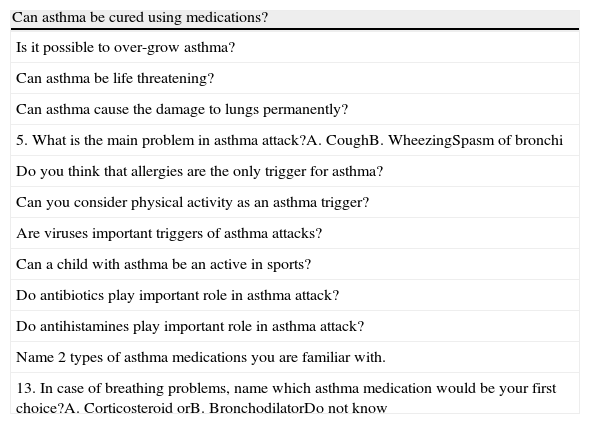

The AEI was conducted by trained educators – respiratory paediatricians and nurses. It was provided in small groups in the form of audio-visual presentation lectures, open discussion/workshops and a handbook titled “Meet your asthma”. The AEI consisted of two half-day sessions. The sessions were designed in the form of five movies and audio-visual lectures – Power Point audio presentation (which lasted approximately 25–45min) and afterwards followed the panel discussion/workshop (which lasted 45min and more) (Appendix 1). The movies and audio Power Point presentation were made in a studio granted by our sponsors and our doctors; patients and their parents participated in them. The complete educational programme and handbook can be found on the Internet website www.decija-astma.com (in Serbian language only). The parents completed a 13-item asthma knowledge questionnaire before AEI, immediately after AEI, and 12 months later (Appendix 2). The level of parental education was defined in accordance to the number of years of education: elementary school (ES), high school (HS), college (C) and university degree (U). The parents gave statements on their level of education. Their diplomas were not checked but their statements were accepted.

The parents in group C were instructed about proper medication inhaler technique when their children were discharged from the hospital. They were also provided with the printed handbook with the AAP. The children of parents participating in this group were scheduled for regular check-ups at the same time as those in group I who received the complete education.

Parental knowledge before, immediately after the education, and 12 months later were scored. Correct answers were scored with 1 and incorrect with 0 points. The sum of correct answers was calculated in percentage of 100% of correct answers before (Score 1), immediately after the education (Score 2) and 12 months later (Score 3). Group C did not attend the AEI and did not have Score 2.

Statistical analysesAll data were statistically analysed using programme SPSS 17 for Windows. Ordinal data were analysed using Pearson chi square test in the form of contingency tables and Fisher exact test if needed. Numerical data in two groups (after testing and verifying normal distribution with Kolmogorov–Smirnov test) were compared with Student t test and for more groups we used Fishers parametric ANOVA (Analysis of variance). A p value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

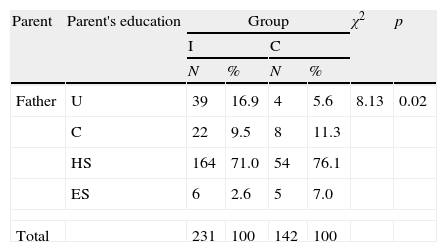

ResultsParticipant characteristicsThe participants were from urban and rural areas of Serbia (90% were inner-city citizens). The average number of the lifetime hospitalisations of their children was 2.65±5.58 (no difference between I and C groups). The distribution of parents in accordance to their education level in groups I and C is presented in Table 1. We had more fathers with a university degrees in group I than in group C (χ2=8.13, p=0.02); there was no difference in regards to the education of mothers (χ2=5.40, p=0.27).

Education of subjects in the Interventional (I) and Control (C) group: ES=elementary school, HS=high school, C=college and U=university degree.

| Parent | Parent's education | Group | χ2 | p | |||

| I | C | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | ||||

| Father | U | 39 | 16.9 | 4 | 5.6 | 8.13 | 0.02 |

| C | 22 | 9.5 | 8 | 11.3 | |||

| HS | 164 | 71.0 | 54 | 76.1 | |||

| ES | 6 | 2.6 | 5 | 7.0 | |||

| Total | 231 | 100 | 142 | 100 | |||

| N | % | N | % | ||||

| Mother | U | 33 | 14.3 | 7 | 9.9 | 5.40 | 0.27 |

| C | 28 | 12.1 | 4 | 5.6 | |||

| HS | 149 | 64.5 | 56 | 78.9 | |||

| ES | 21 | 9.1 | 4 | 5.6 | |||

| Total | 231 | 100 | 142 | 100 | |||

Pearson's Chi-square test.

Total knowledge of asthma in group I increased from 63.2%, (before AEI), to 82.7% of correct answers 12 months after AEI. The increase of knowledge was significant immediately after the AEI (χ2=144.14, p<0.01), and insignificantly increased between AEI and the end of the study and 12 months after the audiovisual education (t=1.45, p=0.45).

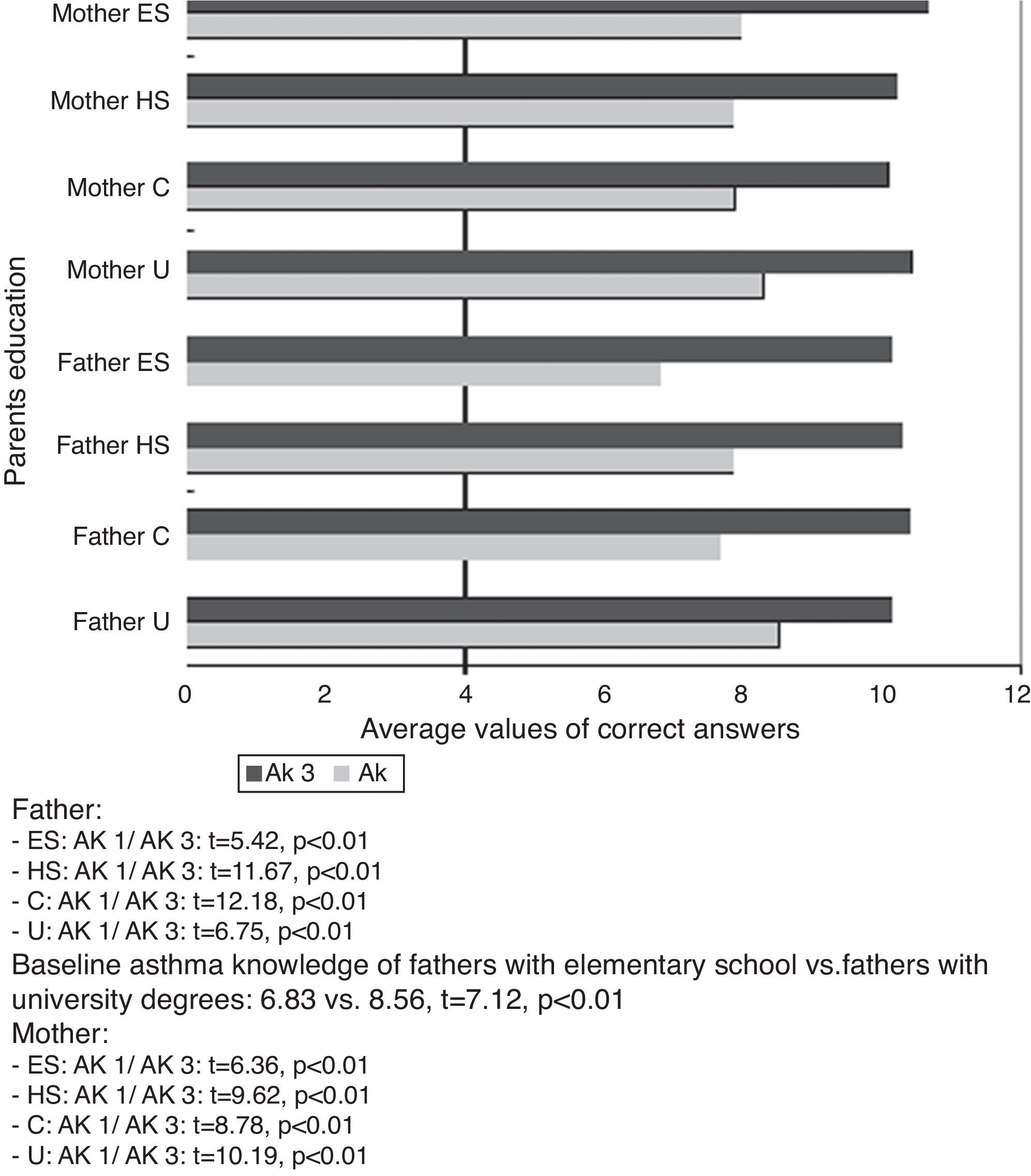

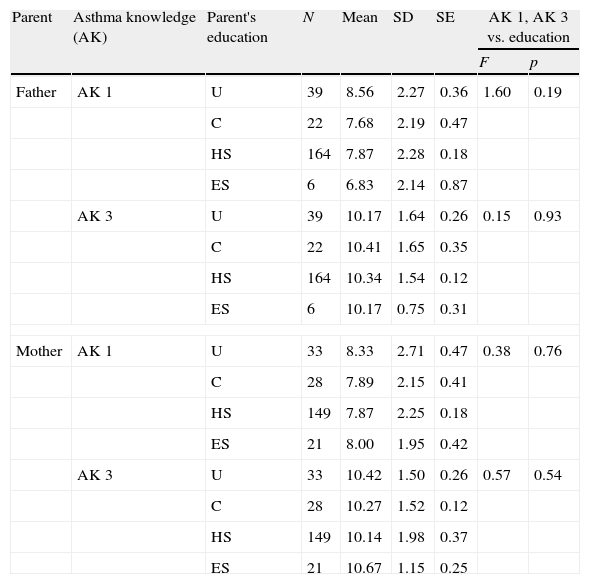

Parental education and asthma knowledge in the educated group I of parents were analysed. All parents significantly increased their asthma knowledge (p<0.01) regardless of their education level (Fig. 2). The differences of the parental baseline (AK 1) and final asthma knowledge (AK 3) were analysed with regard to the parents’ education (Table 2). Taking into consideration the education of the parents, no difference was found in fathers’ baseline asthma knowledge before the AEI (AK 1) (F=1.60, p=0.19). However, the AK 1 of fathers with university degrees was higher than AK 1 of fathers with elementary school (8.56 vs. 6.83, t=7.12, p<0.01). The final, acquired asthma knowledge of fathers in the period of 12 months after the AEI (AK 3) was not significantly different (F=0.15, p=0.93) with regard to their educational level. There was no difference in asthma knowledge of mothers before (F=0.38, p=0.76) and 12 months after the AEI (F=0.57, p=0.54) with regard to their education.

Asthma knowledge (AK – average value of correct answers) of Interventional (I) group of parents before the education (AK 1) and final asthma knowledge (AK 3) vs. parental education (ES=elementary school, HS=High school, C=college and U=university degree).

| Parent | Asthma knowledge (AK) | Parent's education | N | Mean | SD | SE | AK 1, AK 3 vs. education | |

| F | p | |||||||

| Father | AK 1 | U | 39 | 8.56 | 2.27 | 0.36 | 1.60 | 0.19 |

| C | 22 | 7.68 | 2.19 | 0.47 | ||||

| HS | 164 | 7.87 | 2.28 | 0.18 | ||||

| ES | 6 | 6.83 | 2.14 | 0.87 | ||||

| AK 3 | U | 39 | 10.17 | 1.64 | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.93 | |

| C | 22 | 10.41 | 1.65 | 0.35 | ||||

| HS | 164 | 10.34 | 1.54 | 0.12 | ||||

| ES | 6 | 10.17 | 0.75 | 0.31 | ||||

| Mother | AK 1 | U | 33 | 8.33 | 2.71 | 0.47 | 0.38 | 0.76 |

| C | 28 | 7.89 | 2.15 | 0.41 | ||||

| HS | 149 | 7.87 | 2.25 | 0.18 | ||||

| ES | 21 | 8.00 | 1.95 | 0.42 | ||||

| AK 3 | U | 33 | 10.42 | 1.50 | 0.26 | 0.57 | 0.54 | |

| C | 28 | 10.27 | 1.52 | 0.12 | ||||

| HS | 149 | 10.14 | 1.98 | 0.37 | ||||

| ES | 21 | 10.67 | 1.15 | 0.25 | ||||

F=ANOVA test.

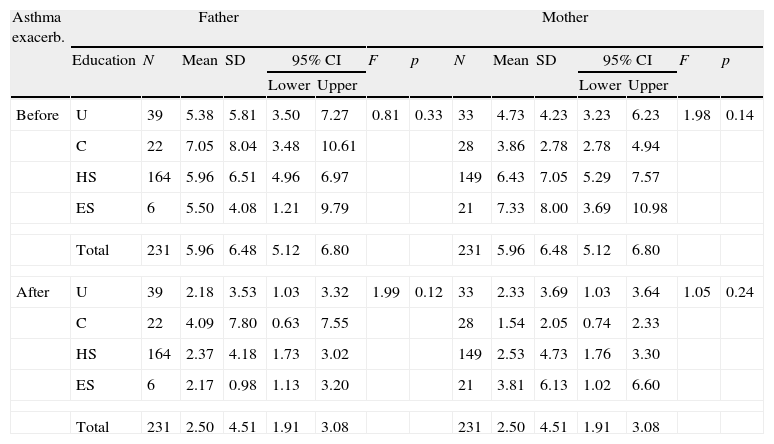

The results of parents’ educational influence on the number of asthma exacerbations in children during 12 months before and after AEI are presented in Table 3. There was no difference in number of asthma exacerbations 12 months before (F=0.81; p>0.05) and after AEI (F=1.99; p>0.05) according to the fathers’ education. There was no difference in number of asthma exacerbations 12 months before (F=1.98; p>0.05) and after AEI (F=1.05; p>0.05) according to the mothers’ education either. However, number of asthma exacerbations 12 months after AEI were significantly lower compared to the number of asthma exacerbations before (5.96:2.50) regardless of the fathers’ (F=40.77; p<0.01) or mothers’ educational degree (F=41.34; p<0.01).

Parental education (ES=elementary school, HS=High school, C=college and U=university degree) related to the number of asthma exacerbations in their children during 12 months before and after AEI (Asthma Educational Intervention).

| Asthma exacerb. | Father | Mother | |||||||||||||

| Education | N | Mean | SD | 95% CI | F | p | N | Mean | SD | 95% CI | F | p | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||||||||||

| Before | U | 39 | 5.38 | 5.81 | 3.50 | 7.27 | 0.81 | 0.33 | 33 | 4.73 | 4.23 | 3.23 | 6.23 | 1.98 | 0.14 |

| C | 22 | 7.05 | 8.04 | 3.48 | 10.61 | 28 | 3.86 | 2.78 | 2.78 | 4.94 | |||||

| HS | 164 | 5.96 | 6.51 | 4.96 | 6.97 | 149 | 6.43 | 7.05 | 5.29 | 7.57 | |||||

| ES | 6 | 5.50 | 4.08 | 1.21 | 9.79 | 21 | 7.33 | 8.00 | 3.69 | 10.98 | |||||

| Total | 231 | 5.96 | 6.48 | 5.12 | 6.80 | 231 | 5.96 | 6.48 | 5.12 | 6.80 | |||||

| After | U | 39 | 2.18 | 3.53 | 1.03 | 3.32 | 1.99 | 0.12 | 33 | 2.33 | 3.69 | 1.03 | 3.64 | 1.05 | 0.24 |

| C | 22 | 4.09 | 7.80 | 0.63 | 7.55 | 28 | 1.54 | 2.05 | 0.74 | 2.33 | |||||

| HS | 164 | 2.37 | 4.18 | 1.73 | 3.02 | 149 | 2.53 | 4.73 | 1.76 | 3.30 | |||||

| ES | 6 | 2.17 | 0.98 | 1.13 | 3.20 | 21 | 3.81 | 6.13 | 1.02 | 6.60 | |||||

| Total | 231 | 2.50 | 4.51 | 1.91 | 3.08 | 231 | 2.50 | 4.51 | 1.91 | 3.08 | |||||

F=value of ANOVA test (GLM general linear model for repeated measures).

Total knowledge of asthma in group C increased insignificantly from 65.5% at the beginning of the study to 67.8% in the period of 12 months later (Z=0.73, p=0.17).

The correlation of parents’ education to the increase of asthma knowledge in group C was not analysed because there was no significant increase in asthma knowledge in this group.

Comparison of asthma knowledgeWe compared asthma knowledge (AK – average value of correct answers) at the beginning of the study (AK 1) and the final, acquired knowledge of asthma (AK 3) between subjects in the groups I and C. There was no difference in baseline asthma knowledge between these groups (8.47 in group C vs. 7.96 correct answers out of 13 in group I; t=1.71, p=0.09). The final knowledge of asthma (AK 3) was significantly higher in group I than in group C (10.25 vs. 8.39 correct answers out of 13; t=7.79, p<0.01).

Discussion and conclusionDiscussionThe organised AEI comprised of audiovisual presentations, handbook titled “Meet your Asthma” and panel discussion/workshops was more successful in achieving better asthma knowledge in I group subjects than featuring instructions about medications and handbook titled “Meet your Asthma” in C group subjects. During the 12-month period after the AEI, educated subjects did not continue to improve their knowledge of asthma no matter what the pattern of their education was (reading the handbook, TV, newspapers, websites, contact with doctors, etc.). We demonstrated that organised AEI was a more appropriate way to transmit asthma knowledge to the target group.

The knowledge of subjects in group C did not increase during the study at all. They did not improve knowledge of asthma by way of reading the handbook or any other way during the study.

The influence of parents’ education on baseline asthma knowledge and on the increase of the parental knowledge of asthma in the group I was not found. All educated subjects significantly increased their knowledge of asthma no matter what the level of their education was. As we expected, fathers with university degrees had higher knowledge of asthma before the AEI, but there was no difference in the knowledge of mothers with different educational degree before the AEI. The reason for this was maybe mothers spent more time and were more engaged with their children with asthma; in our country they often take children to regular check-ups and mostly are hospitalised with children, so they had more contact with medical staff and received more information about asthma. Finally, acquired knowledge of asthma (AK 3) of all educated parents was not significantly different, regardless of their educational level. The parental educational degree did not affect the level of asthma knowledge after the AEI. The motivation of parents and educators and the type of asthma education had the greatest input on the final results.

The correlation of parental education and number of asthma exacerbations in children before and after AEI showed no difference in number of asthma exacerbations 12 months before and after AEI according to the fathers’ or mothers’ educational degree. Many different factors could influence asthma exacerbation (viral infection, allergen exposition, environmental tobacco smoke, stress, etc.) and the educational degree of parents was not a factor. But, educating parents through AEI was very important in preventing an asthma exacerbation. Expectedly, children had more than two times fewer asthma exacerbations 12 months after AEI, regardless of the fathers’ or mothers’ educational degree. That was what we expected of parents educated about all aspects of asthma.

The results from our study are similar to those found in other educational intervention studies, which have been conducted worldwide. The other set of papers reported educational interventions in different settings and with different participants.22–25 Some studies reported significant effectiveness of the educational programme of children and adolescents in terms of morbidity, self-perception of asthma control, and healthcare use.26 Others concluded that asthma education of parents and children could result in lower risk of future emergency department visits and hospitalisations, but remained unclear what type, duration and intensity of education programme was the most effective.27 One school-based asthma intervention suggested that children who had more follow-up visits improved their clinical symptoms and reduced health care use.28 Parental satisfaction and cost effectiveness were favourable for the patients with asthma in the intensively educated group and follow-up group.29 A multilevel, comprehensive, school-based asthma programme improved quality of life outcomes.30 However, in the available literature we found very few studies comparing parents’ education and asthma knowledge.31

Study limitationsThe distribution of parents’ level of education degree was unequal and could be one of the limitations of our study. Another limitation was that most of the children with asthma were previously hospitalised and parents could be individually educated about some segments of asthma before our AEI, which could influence their baseline asthma knowledge. However, the same situation was present in both groups. Another limitation was that the losses to follow-up subjects in group C (26.4%) was higher than in group I (13.5%), which could substantially affect the results. We assumed that good communication and confidence between subjects in group I and educators motivated these parents to complete the study. Therefore, it is speculated that the study results could be compromised. However, this is considered to be just slightly affected because the unequal randomisation ratio of 2:1 provides only a modest loss in statistical power.

ConclusionThe results of our first study on the AEI in childhood asthma reported significant differences between groups I and C in final, acquired asthma knowledge. The impact of audiovisual lectures with workshops/panel discussions/handbook proved to be successful and the best appreciated educational method. The increase of knowledge of parents was directly related to the active education via AEI after an acute asthma episode of a child. The differences between parents in their education were neither related to the baseline knowledge of asthma nor to the increase of their knowledge. The prevalence of asthma exacerbations in children before and after AEI did not correlate to the fathers’ or mothers’ educational degree. The children had more than two times fewer asthma exacerbations after AEI, regardless of the fathers’ or mothers’ educational degree.

Our results, along with many others, clearly confirm the effectiveness of the AEI. Well-designed and correctly applied educational programmes should be considered a part of good clinical practice in childhood asthma. The parental educational degree did not affect the level of asthma knowledge after the asthma educational programme. The motivation of parents and educators and type of asthma education had the greatest influence on final results.

Practice implicationsParents’ education is a cornerstone of good clinical practice in every chronic disease, especially in childhood asthma. Education of parents, after the hospitalisation of a child, will provide and maximise better control of asthma and better quality of life of their children with asthma. This study provided evidence that well-designed, organised audiovisual tools and practical education of motivated parents had more influence on the parental final knowledge of asthma than parental general education level. The parents’ education does not affect the level of asthma knowledge after the AEI. All parents should be educated about asthma regardless of their general education.

FundingEuropean Respiratory Society Grant 2004.

ContributorsRadic S. wrote the first draft of this paper. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts.

Conflict of interest statementSnezana D. Radic has received the European Respiratory Society Grant in 2004.

Zorica M. Zivkovic has no financial disclosures.

Ika M. Pesic has no financial disclosures.

Branislav S. Gvozdenovic has no financial disclosures.

Branislava A. Milenkovic has no financial disclosures.

Dragan D. Babic has no financial disclosures.

Ethical disclosuresPatients’ data protectionConfidentiality of Data: The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

This work was supported by Ministry of Science, Republic of Serbia (Grant No. 41004). The authors would like to thank Ms. Ivana Kalanovic Dylag and Ms. Tatjana Stojkovic for their contribution in proofreading the manuscript.

| First day |

| Lecture 1. What is asthma? |

| Lecture 2. The avoidance of allergens and environmental control |

| Lecture 3. Inhaler technique and compliance |

| Lecture 4. Workshops and discussion |

| Second day |

| Lecture 5. Environmental tobacco exposure |

| Lecture 6. Child with asthma and sports |

| Lecture 7. Workshops and discussion |

| Can asthma be cured using medications? |

| Is it possible to over-grow asthma? |

| Can asthma be life threatening? |

| Can asthma cause the damage to lungs permanently? |

| 5. What is the main problem in asthma attack?A. CoughB. WheezingSpasm of bronchi |

| Do you think that allergies are the only trigger for asthma? |

| Can you consider physical activity as an asthma trigger? |

| Are viruses important triggers of asthma attacks? |

| Can a child with asthma be an active in sports? |

| Do antibiotics play important role in asthma attack? |

| Do antihistamines play important role in asthma attack? |

| Name 2 types of asthma medications you are familiar with. |

| 13. In case of breathing problems, name which asthma medication would be your first choice?A. Corticosteroid orB. BronchodilatorDo not know |