Severe asthma is often poorly controlled and its prevalence in Spanish children is unknown. The aim was to determine the prevalence of difficult-to-control severe asthma in children, the agreement of asthma control between physicians and Spanish Guidelines for Asthma Management (GEMA), and the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) for children and parents.

MethodsObservational, cross-sectional, two-phase, multicentre study. In the first phase, all children who attended pneumology and allergy units during a three-month period were classified according to physicians’ criteria as patients with: asthma, severe asthma, or difficult-to-control severe asthma. Patients aged 6–14 years with severe asthma (difficult-to-control or controlled) were included in the second phase.

Results12,376 asthmatic children were screened in the first phase. According to physicians’ criteria, 8.8% (95% CI 8.3–9.3%) had severe asthma. Of these, 24.2% (95% CI, 21.7–26.8%) had difficult-to-control severe asthma. 207 patients with severe asthma (mean age 10.8±2.3 years; 61.4% male; mean of 5.5±3.4 years since asthma diagnosis) were included in the second phase. Compared to the patients with controlled asthma, children with difficult-to-control asthma had a higher number of exacerbations, emergency room or unscheduled primary care visits in the previous year (p<0.0001, all) and poor HRQoL (p<0.0001, both children and caregivers). 33.3% of patients with controlled asthma according to physicians’ criteria were poorly controlled according to GEMA.

ConclusionsAround one in four asthmatic children with severe disease had difficult-to-control asthma, although one third was underestimated by physicians. Children with difficult-to-control severe asthma had a poor HRQoL that also affected their parents.

Asthma is the most common chronic disease in childhood.1 It is estimated that in economically developed countries approximately 10% of the paediatric population is affected by this disease.2 Due to the absence of a concrete and precise definition of asthma, a lack of standardisation, and the disparity of the diagnostic criteria, studies on the prevalence of this disease vary in methodology and consequently are difficult to compare. Considering these limitations, the available data indicate large geographical differences with a prevalence rate varying from 6.6% to 33.5%.3,4 The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC Phase III, 2005) reported asthma diagnosis figures in Spain that range from 12.8% in children aged 13–14 years to 10.9% in children aged 6–7 years.5

Asthma causes deterioration of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in children and adolescents due to the limitation of daily activities; physical and recreational activities; interference with sleep, academic performance, truancy; and working absenteeism of parents.6 Likewise, the economic burden and HRQoL are worsened by those exacerbations requiring unscheduled visits and emergency care and hospital admissions.

After the remarkable progress in reducing infant mortality from asthma, the current challenge is to set new goals to improve the global control of the disease and to encourage early medical intervention in an attempt to change the course of the disease.7 In this context, the Spanish Guidelines for Asthma Management [GEMA]8 define asthma control as the degree by which its symptoms are absent or by the maximum degree that they can be reduced due to therapeutic interventions and treatment goals met. Some studies estimate that more than half of asthmatics fail to achieve adequate control.9–11 In this regard, difficult-to-control asthma is defined as asthma which is inadequately or poorly controlled despite an appropriate therapeutic strategy that is adjusted to clinical severity. In general, the factors that contribute to asthma being difficult-to-control are not known, however both genetic and epidemiological factors appear to be involved.12 The classification of childhood asthma is in accordance with its severity, symptomatology, rescue bronchodilator requirement, and respiratory function test data. Two major patterns have been defined: episodic (occasional or frequent, depending on the number of exacerbations) and persistent asthma, which cannot be treated as if it were a mild disease, but rather as at least moderate or severe.

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of severe asthma as well as the prevalence of difficult-to-control severe disease in asthmatic children. Additionally, the clinical characteristics of patients with difficult-to-control severe asthma, the agreement between clinical assessment of asthma control and the 2009 GEMA guidelines, the HRQoL of patients and their caregivers, and predictive factors for difficult-to-control severe asthma were assessed.

Materials and methodsThis was an observational, cross-sectional, two-phase, multicentre study conducted in 30 hospitals in Spain. Simultaneous data from two study phases were collected over a period of three months. In the first phase, a daily record was made of all children who attended the pneumology and allergy units of the participating hospitals. The patients were classified according to the physicians’ criteria as patients with: asthma, severe asthma, or difficult-to-control severe asthma. In the second phase, each physician consecutively included six or seven patients with severe asthma (either with difficult-to-control asthma or with controlled asthma). The following inclusion criteria were applied in the second phase: patients of either sex, aged 6–14 years, having a spirometry performed in the previous six months, and diagnosis of severe asthma according to the physicians’ criteria.

The clinical profile of the patients included in the second phase was evaluated by assessing the socio-demographic data, medical history (date of diagnosis, number of exacerbations in the previous year, and number of times that systemic corticosteroids where needed in the previous six months), clinical classification of the asthma type (allergic or non-allergic asthma) and the level of asthma control according to the physicians’ criteria (controlled or difficult-to-control asthma), number of hospitalisations, emergency room visits, and unscheduled primary care visits due to asthma symptoms in the previous six months, relevant concomitant diseases, data from respiratory and allergy testing available in the previous six months (forced vital capacity [FVC], forced expiratory volume in one second [FEV1], plasma levels of immunoglobulin E [IgE], and skin prick test) and current pharmacologic therapy for asthma.

According to the GEMA guidelines,8 the assessment of asthma control was performed by means of the Childhood Asthma Control (CAN) questionnaire,13 the only available questionnaire validated in Spain to estimate the extent to which asthma is controlled in children. This questionnaire has two versions: (1) for children aged 9–14 years, and (2) for parents or legally authorised representatives (children aged 2–8 years). In children aged 6–8 years the questionnaire was completed by the parents or legally authorised representatives. Children/teenagers aged 9–14 years filled out the questionnaire themselves and the parents or legally authorised representatives filled out their own. The questionnaire evaluates nine questions about clinical symptoms in the previous four weeks and scores the results from 0 (good control) to 36 (poor control). A patient's asthma is considered as poorly controlled when the score is 8 or higher.

Health-related quality of life of children was assessed using the 23-item Paediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (PAQLQ).14 The caregivers answered the 13-item Paediatric Asthma Caregiver's Quality of Life Questionnaire (PACQLQ).15 In both cases, lower scores are indicative of worse HRQoL.

Written informed consent was obtained for all patients by the legally authorised representative and patients aged 12 years or more having to provide their own additional informed consent. The study was approved by the ethics committee at Hospital Clínic of Barcelona (Spain).

Statistical analysisQualitative variables were analysed by the Chi-square test or the Fisher exact test, as appropriate, and quantitative variables were analysed using the t-test or the Mann–Whitney test. Prevalence of asthma was calculated over the total number of children attending consultation during the three-month period. Afterwards, prevalence of severe asthma was calculated over the total number of asthmatic patients and prevalence of difficult-to-control severe asthma was calculated over the total number of patients with severe asthma. Agreement between level of asthma control according to the physicians’ criteria and the GEMA guidelines was evaluated by the Kappa index. Logistic regression analysis was applied to determine the predictors of difficult-to-control severe asthma using odds ratio (OR) and its 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS® statistical package for Windows (version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

ResultsA total of 12,376 asthmatic paediatric patients were screened by the 30 participating hospitals. According to the physicians’ criteria, the prevalence of severe asthma in asthmatic children was 8.8% (95% CI, 8.3–9.3%). Of these, 24.2% (95% CI, 21.7–26.8%) had difficult-to-control severe asthma. Globally, the prevalence of asthma in pneumology and allergy paediatric units was 42.8% (95% CI, 42.3–43.4%).

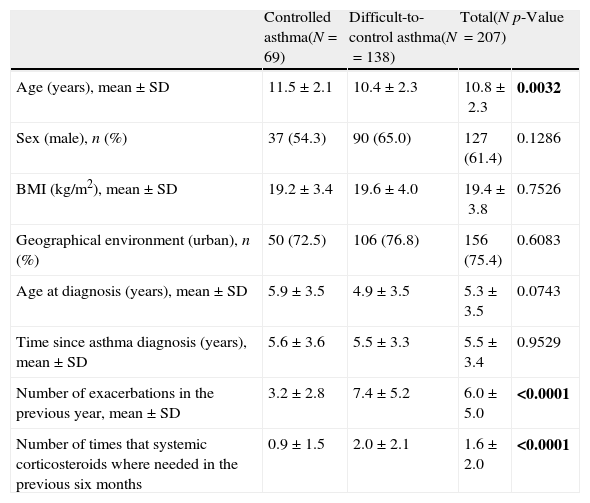

Two-hundred and seven patients with severe asthma according to the physicians’ criteria were included in the second phase of the study. The demographic and clinical characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1. The mean (SD) age was 10.8 (2.3) years, 61.4% were male and the mean time since asthma diagnosis was 5.5 (3.4) years. According to the physicians’ criteria, 33.3% of the population (N=69) had controlled severe asthma and 66.7% (N=138) had difficult-to-control severe asthma. Patients with controlled asthma were slightly older compared to the patients with difficult-to-control asthma (mean of 11.4 [2.1] years vs. 10.4 [2.3] years, p=0.0032). Compared to the patients with controlled asthma, the population with difficult-to-control asthma showed a significantly greater number of exacerbations in the previous year, as well as a higher number of times that systemic corticosteroids were used in the previous six months (mean of 7.4 [5.2] vs. 3.2 [2.8] exacerbations and 2.0 [2.1] vs. 0.9 [1.5] times, respectively (p<0.0001, both)).

Demographic and clinical data of patients with controlled and difficult-to-control asthma according to the physicians’ criteria.

| Controlled asthma(N=69) | Difficult-to-control asthma(N=138) | Total(N=207) | p-Value | |

| Age (years), mean±SD | 11.5±2.1 | 10.4±2.3 | 10.8±2.3 | 0.0032 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 37 (54.3) | 90 (65.0) | 127 (61.4) | 0.1286 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean±SD | 19.2±3.4 | 19.6±4.0 | 19.4±3.8 | 0.7526 |

| Geographical environment (urban), n (%) | 50 (72.5) | 106 (76.8) | 156 (75.4) | 0.6083 |

| Age at diagnosis (years), mean±SD | 5.9±3.5 | 4.9±3.5 | 5.3±3.5 | 0.0743 |

| Time since asthma diagnosis (years), mean±SD | 5.6±3.6 | 5.5±3.3 | 5.5±3.4 | 0.9529 |

| Number of exacerbations in the previous year, mean±SD | 3.2±2.8 | 7.4±5.2 | 6.0±5.0 | <0.0001 |

| Number of times that systemic corticosteroids where needed in the previous six months | 0.9±1.5 | 2.0±2.1 | 1.6±2.0 | <0.0001 |

Significant p-values are marked in bold.

SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index.

Controlled asthma group, missing data (n): BMI (12), exacerbations previous year (1), systemic corticosteroids previous six months (4).

Difficult-to-control asthma group, missing data (n): BMI (25), geographical environment (1), exacerbations previous year (4), systemic corticosteroids previous six months (4).

All patients in the controlled severe asthma group were atopic, while in the group with difficult-to-control severe asthma patients, 89.1% had allergic asthma aetiology. The onset of illness in patients with difficult-to-control severe asthma of allergic aetiology took place at a significantly later age than in non-allergic patients with difficult-to-control severe asthma (5.2 [3.3] years vs. 2.9 [4.2] years, p=0.0036). Regarding concomitant pathologies at the time of the study visit, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis was observed in 67.6% of patients (71.4% of patients with controlled severe asthma and 65.7% of patients with difficult-to-control severe asthma). Other common diseases were atopic dermatitis, suffered by 34.3% of patients (28.6% of patients with controlled severe asthma and 37.2% of patients with difficult-to-control severe asthma) and food allergy, present in 16.4% of children (15.7% in controlled severe asthma group and 16.8% in difficult-to-control severe asthma group).

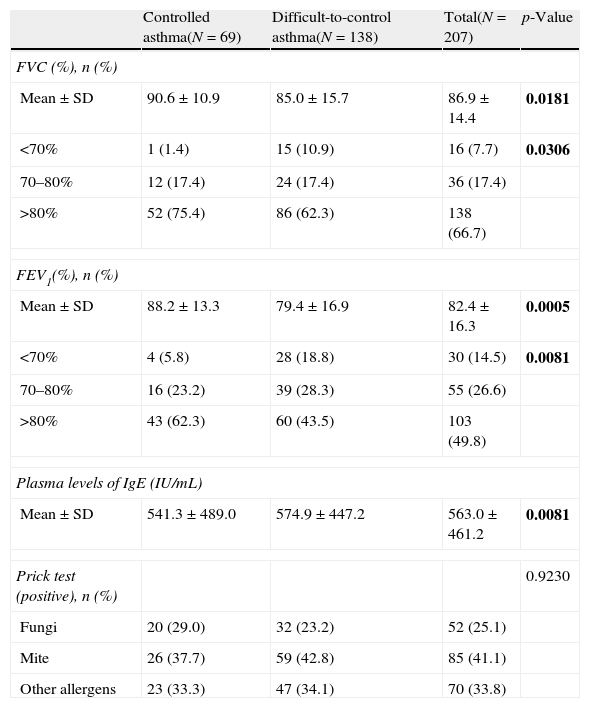

Data from lung function testing showed a higher percentage of patients with difficult-to-control severe asthma with poor performance in spirometry parameters (either FVC or FEV1) compared with controlled severe asthma patients (Table 2). Furthermore, there was a significant difference in the IgE plasma levels in patients with controlled severe asthma vs. patients with difficult-to-control severe asthma although prick test data were comparable between groups. Plasma levels of IgE were found to be higher in the latter (p=0.0081).

Respiratory and allergy testing data of patients with controlled and difficult-to-control asthma according to the physicians’ criteria.

| Controlled asthma(N=69) | Difficult-to-control asthma(N=138) | Total(N=207) | p-Value | |

| FVC (%), n (%) | ||||

| Mean±SD | 90.6±10.9 | 85.0±15.7 | 86.9±14.4 | 0.0181 |

| <70% | 1 (1.4) | 15 (10.9) | 16 (7.7) | 0.0306 |

| 70–80% | 12 (17.4) | 24 (17.4) | 36 (17.4) | |

| >80% | 52 (75.4) | 86 (62.3) | 138 (66.7) | |

| FEV1(%), n (%) | ||||

| Mean±SD | 88.2±13.3 | 79.4±16.9 | 82.4±16.3 | 0.0005 |

| <70% | 4 (5.8) | 28 (18.8) | 30 (14.5) | 0.0081 |

| 70–80% | 16 (23.2) | 39 (28.3) | 55 (26.6) | |

| >80% | 43 (62.3) | 60 (43.5) | 103 (49.8) | |

| Plasma levels of IgE (IU/mL) | ||||

| Mean±SD | 541.3±489.0 | 574.9±447.2 | 563.0±461.2 | 0.0081 |

| Prick test (positive), n (%) | 0.9230 | |||

| Fungi | 20 (29.0) | 32 (23.2) | 52 (25.1) | |

| Mite | 26 (37.7) | 59 (42.8) | 85 (41.1) | |

| Other allergens | 23 (33.3) | 47 (34.1) | 70 (33.8) | |

Significant p-values are marked in bold.

SD: standard deviation; FVC: forced vital capacity; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second; IgE: immunoglobulin E.

Controlled asthma group, missing data (n): FVC (4), FEV1 (6), IgE (8).

Difficult-to-control asthma group, missing data (n): FVC (13), FEV1 (13), IgE (26).

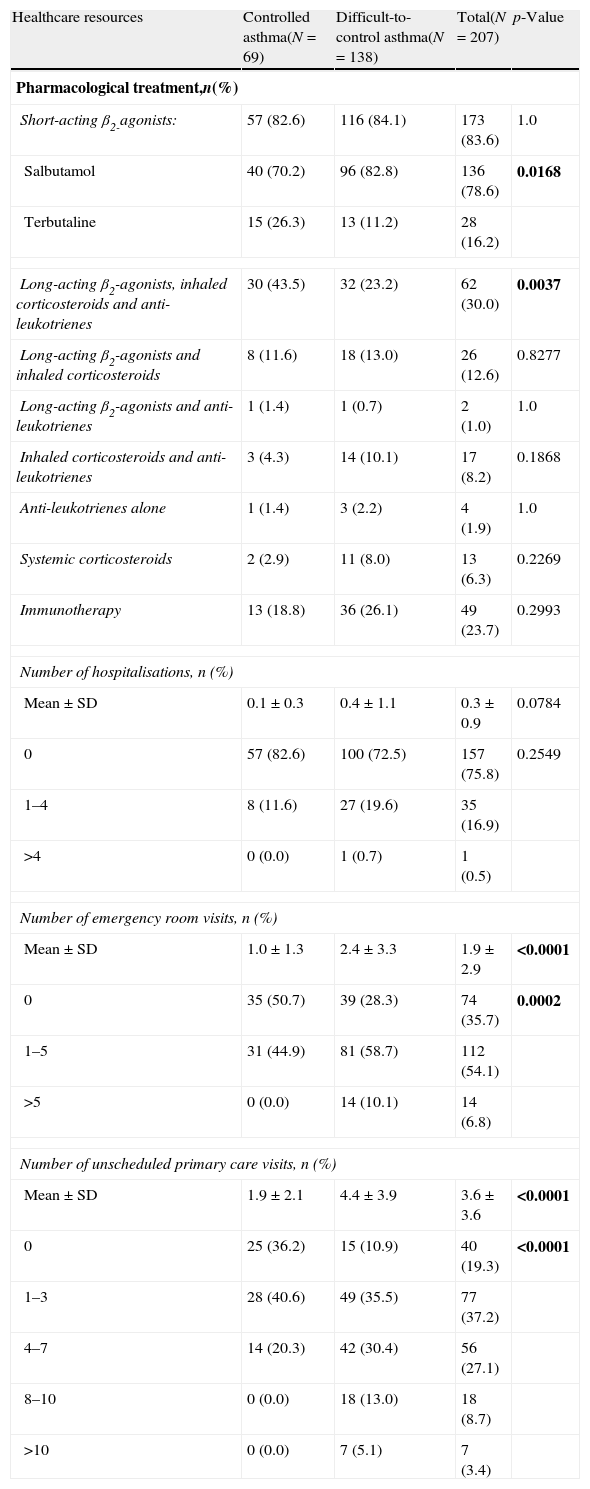

The use of healthcare resources in both groups of patients is detailed in Table 3. All patients were receiving asthma therapy, 83.6% of them using relief medication (inhaled short-acting β2-agonists) as needed, with salbutamol being the most frequent. No significant differences were found between patients with controlled severe asthma vs. patients with difficult-to-control severe asthma regarding the different drugs for treating the disease. The only exception was the combination of long-acting β2-agonists, inhaled corticosteroids and anti-leukotrienes, which was most frequent in the group of patients with controlled severe asthma vs. difficult-to-control severe asthma group (p=0.0037). In addition, the number of emergency room or unscheduled primary care visits during the previous six months was higher in the group of patients with difficult-to-control severe asthma (p<0.0001, both). There was also a trend towards a higher number of hospitalisations in this group compared to the patients with controlled severe asthma (p=0.0784).

Healthcare resources use by patients with controlled and difficult-to-control asthma according to the physicians’ criteria.

| Healthcare resources | Controlled asthma(N=69) | Difficult-to-control asthma(N=138) | Total(N=207) | p-Value |

| Pharmacological treatment,n(%) | ||||

| Short-acting β2-agonists: | 57 (82.6) | 116 (84.1) | 173 (83.6) | 1.0 |

| Salbutamol | 40 (70.2) | 96 (82.8) | 136 (78.6) | 0.0168 |

| Terbutaline | 15 (26.3) | 13 (11.2) | 28 (16.2) | |

| Long-acting β2-agonists, inhaled corticosteroids and anti-leukotrienes | 30 (43.5) | 32 (23.2) | 62 (30.0) | 0.0037 |

| Long-acting β2-agonists and inhaled corticosteroids | 8 (11.6) | 18 (13.0) | 26 (12.6) | 0.8277 |

| Long-acting β2-agonists and anti-leukotrienes | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.0) | 1.0 |

| Inhaled corticosteroids and anti-leukotrienes | 3 (4.3) | 14 (10.1) | 17 (8.2) | 0.1868 |

| Anti-leukotrienes alone | 1 (1.4) | 3 (2.2) | 4 (1.9) | 1.0 |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 2 (2.9) | 11 (8.0) | 13 (6.3) | 0.2269 |

| Immunotherapy | 13 (18.8) | 36 (26.1) | 49 (23.7) | 0.2993 |

| Number of hospitalisations, n (%) | ||||

| Mean±SD | 0.1±0.3 | 0.4±1.1 | 0.3±0.9 | 0.0784 |

| 0 | 57 (82.6) | 100 (72.5) | 157 (75.8) | 0.2549 |

| 1–4 | 8 (11.6) | 27 (19.6) | 35 (16.9) | |

| >4 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Number of emergency room visits, n (%) | ||||

| Mean±SD | 1.0±1.3 | 2.4±3.3 | 1.9±2.9 | <0.0001 |

| 0 | 35 (50.7) | 39 (28.3) | 74 (35.7) | 0.0002 |

| 1–5 | 31 (44.9) | 81 (58.7) | 112 (54.1) | |

| >5 | 0 (0.0) | 14 (10.1) | 14 (6.8) | |

| Number of unscheduled primary care visits, n (%) | ||||

| Mean±SD | 1.9±2.1 | 4.4±3.9 | 3.6±3.6 | <0.0001 |

| 0 | 25 (36.2) | 15 (10.9) | 40 (19.3) | <0.0001 |

| 1–3 | 28 (40.6) | 49 (35.5) | 77 (37.2) | |

| 4–7 | 14 (20.3) | 42 (30.4) | 56 (27.1) | |

| 8–10 | 0 (0.0) | 18 (13.0) | 18 (8.7) | |

| >10 | 0 (0.0) | 7 (5.1) | 7 (3.4) | |

Significant p-values are marked in bold.

Controlled asthma group, missing data (n): rescue medication (6), number of hospitalisations (4), number of emergency room visits (3), and number of unscheduled primary care visits (2).

Difficult-to-control asthma group, missing data (n): rescue medication (10), number of hospitalisations (10), number of emergency room visits (4), and number of unscheduled primary care visits (7).

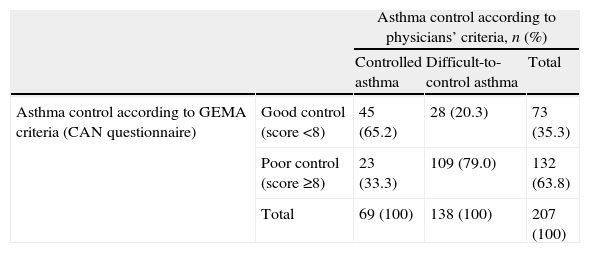

The assessment of asthma control by means of the CAN questionnaire showed higher scores in the group of patients with difficult-to-control severe asthma vs. controlled severe asthma group (14.6 [7.3] vs. 6.2 [5.2], p<0.0001). When examining the concordance between physicians’ assessment and GEMA criteria (Table 4), 33.3% of patients with controlled asthma according to the physicians’ criteria were poorly controlled according to the GEMA guidelines (i.e. CAN questionnaire). Similarly, in 20.3% of cases asthma was considered as difficult-to-control by the physicians, yet according to the CAN questionnaire the patients were classified as having a good control (p<0.0001). In summary, there was a moderate agreement between both criteria (Kappa coefficient: 0.449 [95% CI, 0.321–0.577]).

Asthma control according to physicians’ criteria and GEMA criteria (CAN questionnaire).

| Asthma control according to physicians’ criteria, n (%) | ||||

| Controlled asthma | Difficult-to-control asthma | Total | ||

| Asthma control according to GEMA criteria (CAN questionnaire) | Good control (score <8) | 45 (65.2) | 28 (20.3) | 73 (35.3) |

| Poor control (score ≥8) | 23 (33.3) | 109 (79.0) | 132 (63.8) | |

| Total | 69 (100) | 138 (100) | 207 (100) | |

SD: standard deviation; CAN: Childhood Asthma Control.

Controlled asthma group, missing data (n): CAN questionnaire (1).

Difficult-to-control asthma group, missing data (n): CAN questionnaire (1).

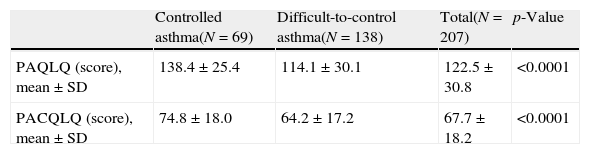

In relation to the HRQoL according to the asthma control (Table 5), significant differences were observed between both groups: patients with difficult-to-control asthma according to the physicians’ criteria showed lower values (i.e. worse HRQoL) in both PAQL and PACQL questionnaires compared to the patients with controlled asthma (p<0.0001, both).

Health-related quality of life of patients with controlled and difficult-to-control asthma according to the physicians’ criteria.

| Controlled asthma(N=69) | Difficult-to-control asthma(N=138) | Total(N=207) | p-Value | |

| PAQLQ (score), mean±SD | 138.4±25.4 | 114.1±30.1 | 122.5±30.8 | <0.0001 |

| PACQLQ (score), mean±SD | 74.8±18.0 | 64.2±17.2 | 67.7±18.2 | <0.0001 |

SD: standard deviation; PAQLQ: Paediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire; PACQLQ: Paediatric Asthma Caregiver's Quality of Life Questionnaire.

Controlled asthma group, missing data (n): PACQLQ (1).

Difficult-to-control asthma group, missing data (n): PAQLQ (7), PACQLQ (2).

Finally, the significant predictive factors for difficult-to-control severe asthma according to the physicians’ criteria were the number of exacerbations in the previous year (OR: 1.23, 95% CI: 1.08–1.41, p=0.0020), and the CAN questionnaire score (OR: 1.19, 95% CI 1.10–1.29, p<0.0001).

DiscussionThe prevalence of asthma in pneumology and allergy paediatric hospital units was approximately 40%. Furthermore, the prevalence of severe asthma in asthmatic children attending these units was around 10%. Of these patients, about a quarter had difficult-to-control severe asthma according to the physicians’ criteria.

These data are relevant and innovative because although there are some studies of asthma prevalence in Spain, they are not focused on paediatric populations.16,17 Quirce et al.18 conducted a study in adult patients and found a prevalence of 3.9% of patients with difficult-to-control severe asthma in Spain. Another Spanish study in adults found a 7.4% of patients with this type of asthma.10

According to our results, the profile of the paediatric patient with difficult-to-control severe asthma was defined as a male with a mean age of 10 years, body mass index of 20kg/m2, who resides in urban settings, with a disease evolution time of five years, and with an average of seven exacerbations per year. A high percentage of these patients were allergic, as previously described.19–22

Regarding spirometry parameters, only one third of patients with difficult-to-control severe asthma had FVC values of less than 80%, and almost half of them had FEV1 values below 80%. The poor relationship between spirometry test and the level of asthma severity is not unusual, considering that there is a generally poor relationship between lung function and asthma symptoms.23 Several studies have analysed this relationship and have shown very weak correlations, especially between FEV1 values and symptoms of asthma in adults24–26 and children.27,28

Some studies have described the impact on the overall cost of the disease and healthcare resources in patients with difficult-to-control severe asthma as although it accounts for a small portion of the asthmatic population, it represents more than 50% of health-related costs.29–31 In Spain, it is estimated that the cost of a patient with severe asthma is almost six times more than that of one with moderate asthma.32 In our study, patients with difficult-to-control severe asthma had a higher use of healthcare resources, particularly an increased number of emergency room and unscheduled primary care visits, but not in terms of hospitalisations.

One third of patients who were classified as controlled according to the physicians’ criteria should be classified as poorly controlled according to the GEMA, thus one third of patients were underdiagnosed by physicians. This suggests that an improvement is needed in training or updating the concept of asthma control and management of clinical disease is needed in order to increase detection and improve proper classification of Childhood Asthma Control. There is evidence that the implementation of an asthma management programme based on recommendations of the guidelines could improve the quality of life in addition to being cost-effective compared to usual clinical practice.33

Asthma prevalence, characteristics, and impact on the lives of patients and caregivers differ according to the time of life, severity, and control of the disease. In relation to the HRQoL, our data show that patients with difficult-to-control severe asthma had a worse HRQoL affecting their caregivers, as previously described.34 The literature shows that an improvement in the quality of life of parents or caregivers also leads to a better response to meet the demands of asthmatic patients.35 Furthermore, the quality of life of caregivers has also been associated with the effectiveness of medications for asthma control in childhood.36

In the present study the factors associated with physician's perception of difficult-to-control severe asthma were the number of exacerbations in the previous year and the CAN questionnaire score. Although the factors that contribute to asthma being difficult-to-control are not clearly identified,12 some studies show a slight association with genetic or environmental factors.12,37 Food allergies,38 allergic rhinitis,39 and especially the HRQoL40 are considered associated with difficult-to-control asthma.

One limitation of this study may arise from its observational design. By including patients who attended allergy or pneumology hospital units we may have slightly overestimated the overall prevalence of asthma, but not the prevalence of difficult-to-control severe asthma. Moreover, since the physicians included patients with diagnosis of severe asthma based on their clinical criteria and not based on standardised criteria, a selection bias may also have been generated. Another limitation of the study could be the assessment of asthma control by the CAN questionnaire, which has a sensitivity and specificity of 77% and 60%, respectively.41

In conclusion, about one in four asthmatic children with severe disease had difficult-to-control severe asthma, although one third of them were underestimated by physicians. Difficult-to-control severe asthma affected HRQoL of children and their parents. Given the clinical and economic relevance of the difficult-to-control severe asthma in paediatric patients and the limited information available on this population, this study provides valuable information that should help to improve the diagnosis and management of difficult-to-control severe asthma in childhood.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

FundingThis study was supported by Novartis Farmacéutica, S.A., Spain.

Editorial assistance was supported by Diana Macias/Eva Mateu and Biostatistics by Cristina López from TFS.