Drug provocation tests (DPTs) are the gold-standard method to diagnose non-immediate hypersensitivity reactions (NIHSR) to beta-lactam antibiotics (BL) in children. Our aim was to compare the negative predictive value (NPV) of one-day (short) DPT versus 3–7 days (extended) DPT for the diagnosis of NIHSR to BL in paediatric age. A secondary aim was to compare confidence on drug re-exposure after short and extended negative DPTs.

MethodsThe occurrence of HSR on drug re-exposure and drug refusal after negative diagnostic DPTs were evaluated in children/adolescents with a history of NIHSR to BL using a questionnaire performed six months to ten years after DPT. Patients were divided into two groups according to the protocol performed: short DPT vs. extended DPT.

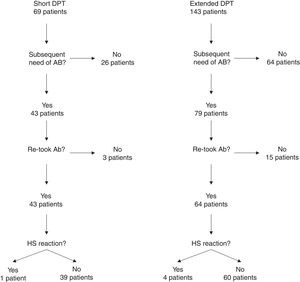

ResultsWe enrolled 212 children and adolescents (86 females, 126 males, mean age at DPT 5.52 years, p25=3 years, p75=7.25 years): 69 tested with short DPT, and 143 with extended DPT. The NPV of both types of DPT together was 95.2%. The NPV of short DPT was 97.5% and the NPV of extended DPT was 93.8% (p=0.419). After negative DPT, beta-lactams were refused by carers in 14.75% of the children requiring subsequent treatment, 6.98% in the short DPT group and 18.99% in the extended DPT group (p=0.074).

ConclusionsIn our paediatric sample, prolonging drug administration did not increase the NPV of diagnostic DPT for NIHSR to BL or reduce drug refusal. Altogether, the data here reported suggest that, however intuitive, prolonging DPT is not beneficial in the parameters analysed.

Around 10% of people avoid some type of medication due to fear of allergic reactions.1 Suspicion of drug allergy has a great impact in clinical practice.2 However, only a small percentage of patients are confirmed to have drug HSR in subsequent work-up. This over-diagnosing is particularly frequent among children1,3–8 and allergy “mislabelling” often persists into adulthood.

In children, beta-lactam antibiotics (BL) are the most common medications suspected of being involved in drug HSR and can mediate all ‘Gell and Coombs’ types of HSR.9 Most suspected HSR to BL in children are mild non-immediate skin eruptions occurring in the context of treatment for infection.10,11 Viral infections are the most common cause of maculopapular or urticarial eruptions in children, leading to frequent misdiagnosis of HSR to concurrent BL treatment.4,6,12

It is generally agreed that drug provocation tests (DPT) with the culprit antibiotic are the “gold standard” for the diagnosis of non-immediate HSR to BL.13,14 Clinical history criteria cannot accurately predict BL allergy15 whereas blood allergy tests16 and other allergy in vivotests, such as intradermal testing or patch testing, have low sensitivity in this clinical context7,8,10,12,17,18 and may be difficult to implement in young children. Recent evidence suggests that, after a careful clinical history, non-immediate mild cutaneous eruptions in children should be investigated by “up-front” DPT with the culprit drug,12,19–22 and such an approach has been included in some guidelines.23

The negative predictive value (NPV) of DPTs for non-immediate HRS to BL has been reported to be as high as 90–98%4,8,24 with some variation attributable to differences in the populations tested and DPT protocols. However, some patients do have HSR after negative DPT, and no current method can further identify which patients are at risk of HSR on re-exposure. Some DPT modifications were proposed to improve accuracy, including:

- 1.

Extended DPT protocols,17,24–27 as it has been argued that one-day (“short”) DPT protocols might provide an exposure that is too small to elicit a full non-immediate HSR. It is also well known that, after a negative DPT, some patients, carers or attending physicians remain reluctant to use or prescribe the previously suspected medication.28 Extended protocols were proposed to also increase patients/physicians’ confidence in subsequent use of the drug.29

- 2.

Retesting after a first negative DPT with the culprit drug. However, recent evidence suggests that retesting adds little diagnostic benefit.30,31

Data directly comparing short DPT versus extended DPT protocols in the context of non-immediate HSR in children is scarce. The primary aim of this study is to compare the NPV of one-day (short) DPT versus 3–7 days (extended) DPT protocols for the diagnosis of non-immediate cutaneous HSR to BL in paediatric age. A secondary aim is to compare the frequency of drug use (re-exposure) after short and extended negative DPTs. We did not intend to compare the performance of the two protocols in terms of diagnostic sensitivity.

MethodsWe retrospectively collected data from 212 children and adolescents with a negative diagnostic DPT performed between 2007 and 2015 as part of the investigation of non-immediate cutaneous HSR to BL in two Hospitals in Portugal (Centro Hospitalar do Porto, CHP, in Porto, and Hospital Dona Estefânia, HDE, in Lisbon), and completed telephone questionnaires to the carers of the patients between 2015 and 2017.

Drug provocation testsAll patients tested had previous cutaneous, non-severe, non-immediate HSR to BL (defined as reactions that occurred more than 1 hour after the previous dose intake and with characteristic manifestations of non-immediate hypersensitivity). After informed consent by the parents/carers, the patients were tested “up-front” (i.e., without previous skin testing) using one of two DPT protocols with the culprit drug (diagnostic DPT):

- 1.

“short” DPT – one-day administration of an age- and weight-adjusted dose of the suspected drug according to ENDA guidelines (total dose was calculated taking into consideration the daily doses and administration intervals recommended to treat the infection present when the suspected HSR occurred). The whole DPT protocol was usually performed in day-hospital and the total dose was divided in 2–4 administrations with intervals of 30–60min, followed by a vigilance period of at least 3h before medical discharge. No further doses were administered at home;

- 2.

“extended” DPT – the first day was identical to the “short” DPT protocol but antibiotic administration continued at home on the following days using standard doses “as per treatment” until the number of doses that reportedly triggered the reaction was achieved.

The assignment to short or extended DPT in CHP was chronological: from 2007 to 2012 all children were tested with short DPTs and after 2012 all were tested with extended DPT. In HDE, the assignment to short or extended DPT was random.

All patients included in this study had negative DPTs. DPTs were considered negative when no symptoms developed during DPT or in the seven days after the last drug administration. After a negative DPT, patients’ parents and carers were explained the result and limitations of the DPT and were instructed that BL could be safely used in subsequent bacterial infections. A written report was provided to the patient and the assistant physician. Drug HS “labelling” and the Hospital's informatics limitations to beta-lactam prescription were removed.

Re-exposure questionnaireSix months to ten years after negative DPT, the carers of patients were contacted by telephone to obtain information regarding subsequent use of beta-lactams. A standard questionnaire with the following questions was completed:

- 1.

After the negative DPT, was the patient administered the tested beta-lactam antibiotic ever again?

- 2.

If the answer to question 1 was positive, did the child have manifestations of HSR? If so, what were the manifestations?

- 3.

If the answer to question 1 was negative (patient was never treated with BL again), what was the reason? Were BL not needed? Were the patient/carer/attending physician afraid of using the suspected drug?

NPV were calculated and compared using chi-square test using STATA (StataCorp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX, USA: StataCorp LLC). The distribution of other variables between the two groups were compared using Student's t-test, Fisher-exact-test and chi-square test where appropriate. The level of significance considered was α=0.05.

Ethics and consentThis study was approved by an institutional ethics committee and the database was registered in the Portuguese Data Protection Authority. Children's parents or the entitled caregivers signed an informed consent for the study.

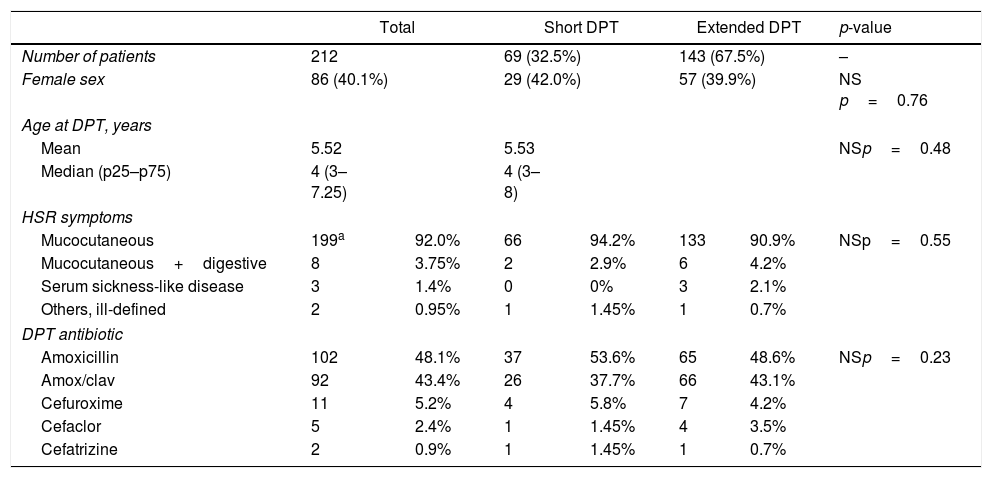

ResultsA total of 212 patients were included: 151 in CHP and 61 in HDE, 86 females, 126 males, average age at DPT 5.52 years (median four years, p25–p75: 3–7.25 years). Sixty-nine (32.5%) patients were tested with short DPT and 143 (67.5%) with extended DPT. No significant differences in age, sex, type of reaction or DPT antibiotic were observed between the groups (Table 1).

Short vs. extended DPT sample characteristics.

| Total | Short DPT | Extended DPT | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 212 | 69 (32.5%) | 143 (67.5%) | – | |||

| Female sex | 86 (40.1%) | 29 (42.0%) | 57 (39.9%) | NS p=0.76 | |||

| Age at DPT, years | |||||||

| Mean | 5.52 | 5.53 | NSp=0.48 | ||||

| Median (p25–p75) | 4 (3–7.25) | 4 (3–8) | |||||

| HSR symptoms | |||||||

| Mucocutaneous | 199a | 92.0% | 66 | 94.2% | 133 | 90.9% | NSp=0.55 |

| Mucocutaneous+digestive | 8 | 3.75% | 2 | 2.9% | 6 | 4.2% | |

| Serum sickness-like disease | 3 | 1.4% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 2.1% | |

| Others, ill-defined | 2 | 0.95% | 1 | 1.45% | 1 | 0.7% | |

| DPT antibiotic | |||||||

| Amoxicillin | 102 | 48.1% | 37 | 53.6% | 65 | 48.6% | NSp=0.23 |

| Amox/clav | 92 | 43.4% | 26 | 37.7% | 66 | 43.1% | |

| Cefuroxime | 11 | 5.2% | 4 | 5.8% | 7 | 4.2% | |

| Cefaclor | 5 | 2.4% | 1 | 1.45% | 4 | 3.5% | |

| Cefatrizine | 2 | 0.9% | 1 | 1.45% | 1 | 0.7% | |

Mucocutaneous includes maculopapular exanthema with mucous angioedema (n=3), maculopapular exanthema without angioedema (191), skin erythemas (4) and urticariphorm exanthema (1).

DPT: drug provocation test; HSR: hypersensitivity reaction; MPE: maculopapular exanthema; Amox/clav: amoxicillin and clavulanate; NS: non-significant.

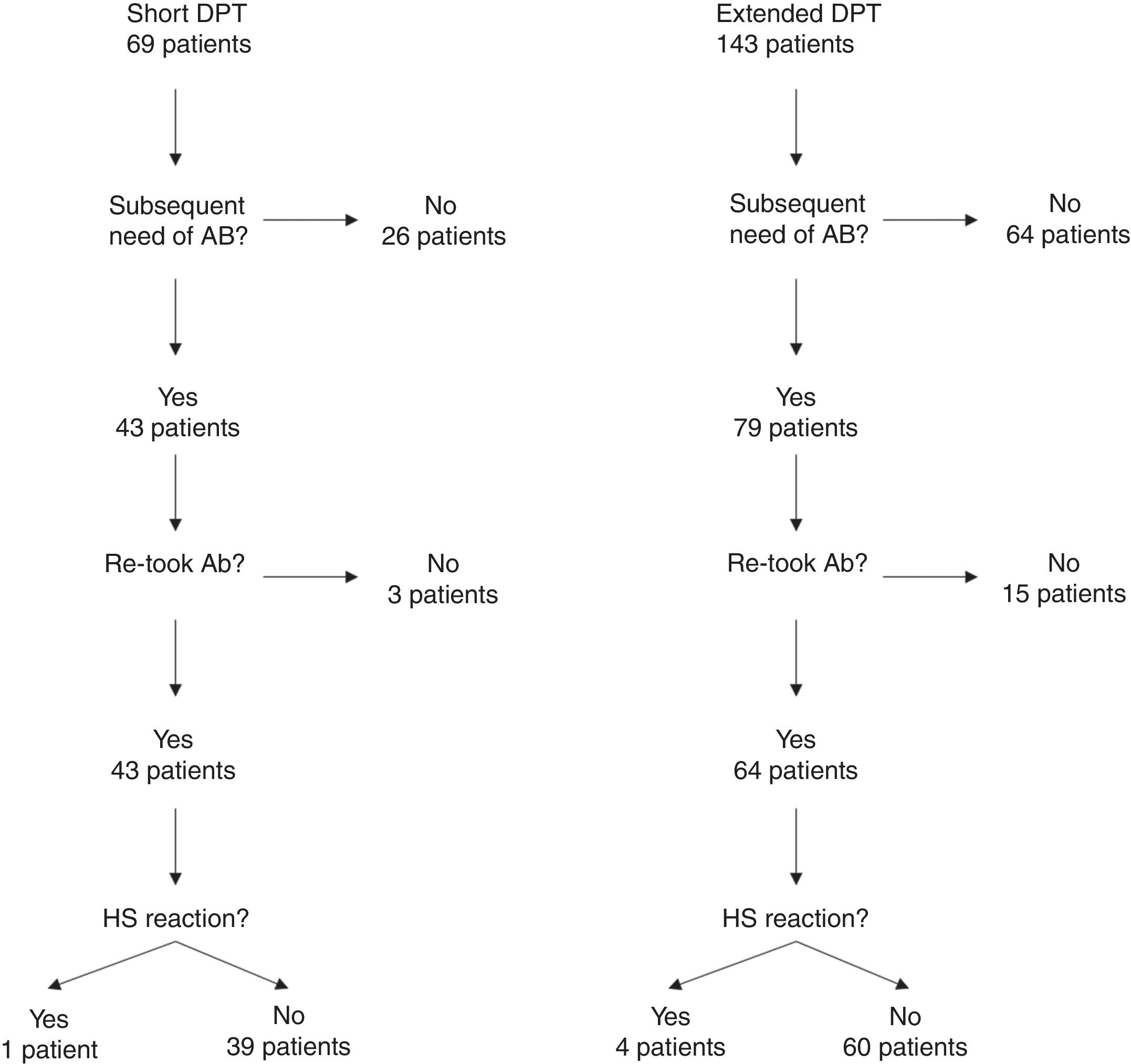

One hundred and four of the 212 patients (49.1%) were re-exposed to beta-lactams months to years after the negative DPT (Fig. 1): 40/69 (58%) in the short DPT group and 64/143 (44.8%) in the extended DPT group (p=0.071). Many factors may have contributed to the frequency of subsequent antibiotic use, e.g., time interval between DPT and telephone interview, rate of infections, age of the patient, among others. Carer/assistant physician refusal of subsequent use will be analysed below. Among the patients re-exposed to BL after negative DPT, 5/104 patients reported a suspected HSR on re-exposure (NPV was 95.2%, when both DPT protocols were analysed together).

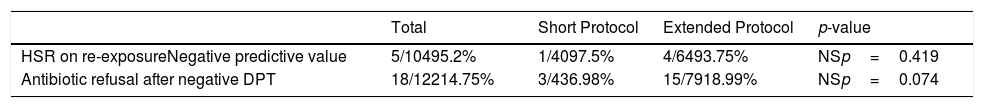

On re-exposure, only 1/40 patients in the short DPT group developed a suspected HSR (NPV: 97.5%) compared to 4/64 patients in the extended DPT group (NPV: 93.75%), p=0.419 (Table 2). All five patients who developed HSR on re-exposure had maculopapular exanthema (MPE) on the HSR index and again presented MPE on re-exposure. All five were male, average age at DPT was five years and the BL involved were amoxicillin/clavulanate in three patients and amoxicillin in two.

Negative predictive value of the DPT and antibiotic refusal after negative DPT.

| Total | Short Protocol | Extended Protocol | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSR on re-exposureNegative predictive value | 5/10495.2% | 1/4097.5% | 4/6493.75% | NSp=0.419 |

| Antibiotic refusal after negative DPT | 18/12214.75% | 3/436.98% | 15/7918.99% | NSp=0.074 |

HSR: hypersensitivity reaction; DPT: drug provocation test; NS: non-significant.

We then focused on those patients who, after negative DPT, required BL for subsequent infections but refused the treatment due to fear of HSR. The decision to refuse treatment might have been taken by the patient, carers or prescribing physicians.

Despite previous negative DPT, antibiotic treatment was refused in 18 out of 122 patients that required BL (14.75%). Age was higher in those refusing the drug (6.44 years of age vs. 4.47 years, p=0.021). No significant differences were observed between patients who refused the drug and those re-exposed in terms of type of initial HSR (mucocutaneous reaction in 16/18 vs. 98/104, respectively, p=0.335). The most frequent culprit drug in patients who refused re-exposure was amoxicillin/clavulanate (11 patients, 61.1%) and amoxicillin in the remaining seven patients (38.9%). In patients who were re-exposed (104 patients), the suspected BL were amoxicillin/clavulanate in 40 patients (38.5%), amoxicillin in 57 (54.8%), cefuroxime in five (4.8%) and cefaclor in two (1.9%). Amoxicillin/clavulanate was more frequent in those refusing retreatment (p=0.072).

In the short DPT group, refusal occurred in three out of 43 (6.98%) of the patients that were subsequently prescribed BL antibiotics, whereas in the extended DPT group, refusal occurred in 15 out of 79 patients (18.99%), p=0.074.

DiscussionIn this study we aimed to determine whether prolonging the exposition to the antibiotic improved the negative predictive value of DPTs for the diagnosis of mild non-immediate HSR to beta-lactams in children. This is a relevant question because several alterations to the DPT protocols have been suggested and implemented but few data have been published directly comparing the two methods to confirm additional benefits. We evaluated both the recurrence of HSR symptoms on re-exposure, and drug refusal after negative one-day DPTs versus longer DPTs.

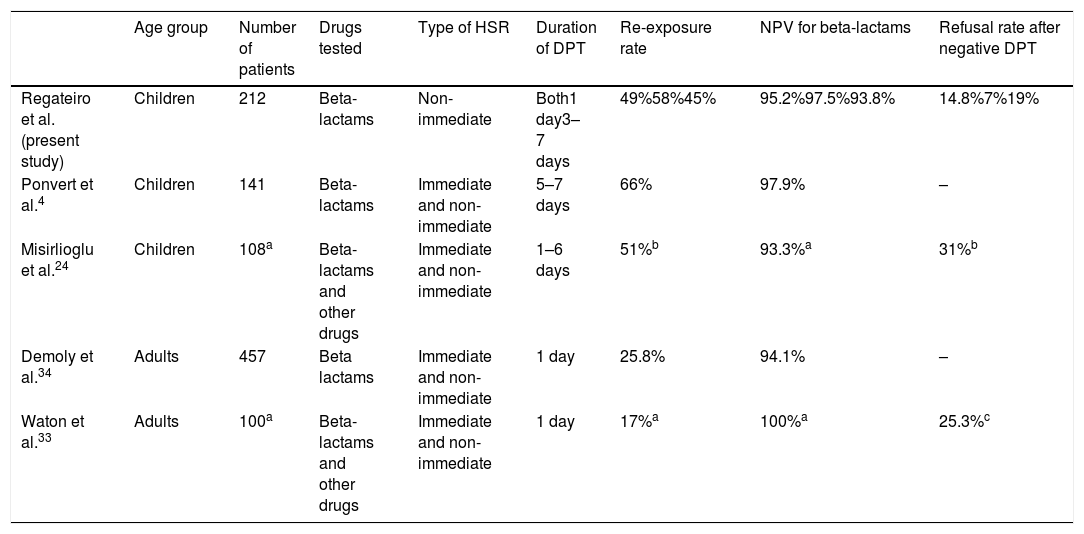

Our results confirm the high NPV of diagnostic DPTs in non-immediate HSR to beta-lactams in children (95.2%, both DPT protocols together). Similar values were reported in other studies (Table 3) despite differences in methodologies, type of HSR and populations enrolled. When comparing the NPV of short versus extended DPTs, we found no differences between protocols, although there were more suspected false negatives in the extended group (NPV short DPT 97.6% vs. NPV extended DPT 93.8%). Such a small difference is likely clinically irrelevant.

Summary of current study and previously reported findings.

| Age group | Number of patients | Drugs tested | Type of HSR | Duration of DPT | Re-exposure rate | NPV for beta-lactams | Refusal rate after negative DPT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regateiro et al. (present study) | Children | 212 | Beta-lactams | Non-immediate | Both1 day3–7 days | 49%58%45% | 95.2%97.5%93.8% | 14.8%7%19% |

| Ponvert et al.4 | Children | 141 | Beta-lactams | Immediate and non-immediate | 5–7 days | 66% | 97.9% | – |

| Misirlioglu et al.24 | Children | 108a | Beta-lactams and other drugs | Immediate and non-immediate | 1–6 days | 51%b | 93.3%a | 31%b |

| Demoly et al.34 | Adults | 457 | Beta lactams | Immediate and non-immediate | 1 day | 25.8% | 94.1% | – |

| Waton et al.33 | Adults | 100a | Beta-lactams and other drugs | Immediate and non-immediate | 1 day | 17%a | 100%a | 25.3%c |

Refusal of the suspected drug after negative DPT remains a significant issue. In our study, a total of 14.75% of patients were refused BL after a negative DPT. In our sample, extended protocols did not increase confidence in subsequent use and, in fact, drug refusal was higher in the extended DPT group. The reasons for this are unclear and were not explored in our study. We may speculate that psychological factors, such as a “backfire effect”,32 may have played a role. We noted that refusal was more frequent in children tested with amoxicillin/clavulanate and we speculate that perhaps some non-allergic side effects of longer treatments with amoxicillin/clavulanate, such as digestive symptoms, may have influenced subsequent decision to use this antibiotic.

Altogether, our results showed no benefit in prolonging administration to test non-immediate HSR to beta-lactams in children in the parameters analysed. Previously published literature argued for the safety of extended DPTs and reported that some patients developed HSR symptoms only after several days of drug administration during extended DPTs (in adults).25–27 It is however unclear whether these patients would have developed these delayed symptoms if a short DPT had been performed. Data directly comparing sensitivity, NPV and re-exposure confidence of short versus extended DPTs protocols is generally lacking and our study addresses the latter two questions.

Our study included a large number of children with similar characteristics in both groups (e.g., age, type of HSR or suspected antibiotic). Both DPT protocols were performed in the two hospitals to mitigate differences in procedures, personal recommendations or regional differences. In our study, a large number of patients (104/212, 49.1%) were re-exposed to the culprit drug subsequent to negative DPT. A wide variation on re-exposure rates has been reported (Table 3) and the reasons for avoidance have been explored elsewhere.33 The high percentage of re-exposure in our study may, at least in part, be explained by the long period between the DPT and the questionnaire in some patients, and the young age of the patients (e.g., children have more frequent infections providing more possibilities of antibiotic prescription, parents are possibly more abiding to physicians’ prescriptions than adult individuals deciding on their own health).

We are aware of some limitations in our study. We used a questionnaire to evaluate re-exposure and drug refusal. Some carers were interviewed several years after DPT and re-exposure, and this might introduce some recall bias. Although we tried to confirm that patients reporting HSR on re-exposure were indeed describing HSR symptoms, no additional allergological workup was performed to confirm true sensitisation. It has been suggested that, as with index event, some subsequent HSR reports on re-exposure are not “real” HSR4,24 and this might have underestimated the NPV in our study (however, at an expected rate in the two protocols). The presence of non-allergic side-effects, likely arising more frequently during extended DPT, was not evaluated in our study and this might influence willingness to use the same drug besides fear of the HSR. The hypothetical influences of the time intervals between HSR and DPT and also between DPT and re-exposure were not analysed. However, these putative effects are mitigated by the fact that, analysing a paediatric population (average age at DPT=5.52 years), these intervals were never very long.

In conclusion, we did not find additional benefits in prolonging DPT both in terms of NPV and confidence for antibiotic use. However intuitive, any modifications of DPT protocols should be adequately compared with previous standard practice for sensitivity, specificity, predictive values, side-effects and, importantly, patients/carers adhesion to the DPT result. Given the low event rate of HSR on re-exposure after negative DPT, studies in large populations are required to determine the optimal length of DPT. Finally, the diagnostic performance of DPTs is always limited by the incomplete mimicking of all “real-life” conditions: DPTs are usually performed in “controlled” settings, whereas some HSR symptoms may only arise in the presence of co-factors occurring in “real-life” situations, e.g. during infection, after physical exercise, or NSAIDs intake. Other issues under investigation, such as the development of drug resistance or drug sensitisation during diagnostic procedures, might also contribute to determine the risk/benefit of prolonged exposition.

FundingThe authors declare that no funding was received for the present study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors thank Dr. Gearoid McMahon for the insightful comments on the manuscript.