Endovascular Aneurysm Repair (EVAR) for the treatment of aortic abdominal aneurism has been shown to improve short-term survival and quality of life as compared to Open Repair (OR), while reducing the rate of serious complications and allowing for the treatment of more patients.

ObjectivesTo examine the cost-effectiveness of EVAR compared to OR in the treatment of aortic abdominal aneurism in the Portuguese context using a model previously developed in the UK.

MethodologyWe adapted an international economic evaluation model to the Portuguese situation, assuming that the health benefits of EVAR observed in clinical trials would also apply to Portuguese patients. We carried out an expert panel survey to calculate the resource use associated with the intervention and its short and long-term consequences, valued with Portuguese prices.

ResultsThe major cost difference in the primary intervention (difference of 3,064 € in favor of OR) is related to the cost of the endograft/graft. No major differences are observed in the total cost of complications and re-interventions between the two procedures. EVAR represents a cost of 16,709 € over lifetime compared to 12,130 € for OR. Using data from the literature we show that EVAR allows for 0.17 additional undiscounted years of life and 0.091 additional undiscounted quality-adjusted life years. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of EVAR is of 65,605 €/QALY.

ConclusionEndovascular repair of aortic abdominal aneurysm represents an effective alternative and has been used increasingly in Portugal and elsewhere. Our study shows that its cost-effectiveness is currently above the commonly accepted threshold in Portugal, but that the economic value of EVAR would greatly improve if benefits were confirmed in the long run after the intervention. Under these circumstances, EVAR would become an economically valuable intervention that could be adopted on a large scale in Portugal.

O tratamento endovascular (EVAR) do aneurisma da aorta abdominal tem sido apontado, nos últimos anos, como uma alternativa bastante atrativa à cirurgia convencional. Não obstante tais benefícios clínicos e percepcionados pelos doentes, os estudos de avaliação económica parecem não ser tão consistentes, o que requer algumas considerações aquando da utilização desta opção terapêutica em larga escala.

ObjetivosAvaliar, no contexto Português, o custo-efetividade do EVAR no tratamento do aneurisma da aorta abdominal comparado com o tratamento por cirurgia convencional, usando um modelo desenvolvido previamente no Reino Unido.

MetodologiaOs benefícios foram baseados em estudos clínicos internacionais, assumindo que tais resultados podem ser aplicados ao contexto Português. Constituiu-se um painel de peritos para apurar a utilização de recursos associados à intervenção bem como as consequências a curto e médio prazo (valorizados com preços de Portugal).

ResultadosA diferença de custos na intervenção primária entre o EVAR e o tratamento por cirurgia convencional, deveu-se ao preço da endoprótese. Não se verificaram diferenças, entre ambos os procedimentos, no que respeita ao custo total associado às complicações e reintervenções. O rácio custo-efetividade incremental (ICER) do EVAR foi de 65,605€/QALY.

ConclusõesO tratamento endovascular do aneurisma da aorta abdominal apresenta resultados que parecem comprovar uma elevada efetividade tendo sido utilizada, nos últimos anos, de forma crescente um pouco por todo o mundo. Apesar dos resultados custo-efetividade, aqui apurados, estarem acima do que que é considerado limiar de aceitação em Portugal, o valor económico do EVAR melhoraria se se confirmassem os benefícios a longo prazo que, alguns dos estudos recentes, parecem apontar. Nessas circunstâncias, o tratamento endovascular tornar-se-ia uma intervenção economicamente interessante que, aliada aos bons resultados ao nível da efetividade e da qualidade de vida dos doentes, poderia ser indicada para um maior número de situações clínicas.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a serious health condition with a high mortality risk in developed countries. For example, in Canada AAA is the 10th leading cause of death in men 65 years or older.1 The risk of AAA rupture is low, but it increases with the increasing diameter of the aneurysm. In case of AAA rupture mortality is very high, e.g., it has been estimated to vary between 85% to 95% in the Netherlands.2–4 As aneurysms commonly remain asymptomatic until they rupture, a close surveillance of the diameter is needed. Elective abdominal aneurysm repair is usually indicated for aneurysms with a diameter greater than 5.5cm.1,5 Mortality in case of elective aneurysm repair is by contrast lower, below 5%.6–9

Over the past 15 or 20 years the treatment of AAA has changed considerably. Traditionally AAA has been treated through conventional Open Surgical Repair (OR), which is a major but generally successful procedure, with established and definite mortality risk and complication rate, although its long-term re-intervention rates are often underestimated. However, the Endovascular Aneurysm Repair (EVAR) has increased over the recent years as a substitute for OR. It is a minimally invasive alternative to OR, first performed by Volodos in Kharkov, Ukraine and published in 1986.5 Since EVAR is less invasive compared to conventional OR, it intuitively leads to fewer postoperative complications, faster recovery, and shorter hospital stays.6,10 This advantage clearly suggests that this is the preferred procedure for high-risk patients.11–13

While the outcomes and durability of OR are well established, some concerns remain regarding the durability and long-term results of EVAR, namely its increased need for re-interventions and benefits on long-term survival.10 On the one hand, trials indicate that 30-days all-cause mortality risk increases by 4.61 (Hazard Ratio HR) (p<0.001) with OR as compared to EVAR. Also, long-term all-cause mortality risk increases by 1.24 (HR), and long-term AAA mortality risk by 4.37 (HR) after OR as compared to EVAR, when adjusted for different variables.14 However, there is a concern for complications and re-intervention rates, and the literature shows widely varying results. Also, EVAR is considered to be an expensive procedure,2,5,7,8,11 with a need for close surveillance of endografts over many years, and possible conversion to OR.15 The cost comparison between EVAR and OR is, however, also controversial. Indeed, Mani et al.16 observed similar clinical and hospital-related costs for both procedures, and Stroupe et al.17 lower costs for EVAR; conversely, Epstein et al.18 estimated that lifetime costs were higher after EVAR by 3,758£/4,491€ (15,823 £/18,909 € for EVAR versus 12,065 £/14,418 € for OR).

Despite these possible limitations, EVAR has increasingly replaced OR among older patients not suited for the open-surgery procedure, due to its greater short-term efficacy. For example, in the US the number of elective AAA treated with OR fell from 17,784 to 8,451 between 2001 and 2006, while the number of patients treated with EVAR increased from 11,171 to 21,725 in the same period.19 Although EVAR is certainly promising in clinical terms, it potentially imposes an additional financial burden on the National Health Service (NHS). Given the adverse economic context and the deficit crisis of the Portuguese state, it is necessary now more than ever to carefully assess these potential additional costs and evaluate whether they are worth it. To do so, we perform an economic evaluation measuring costs and consequences of EVAR as compared to OR for Portugal, from the National Health Service perspective.

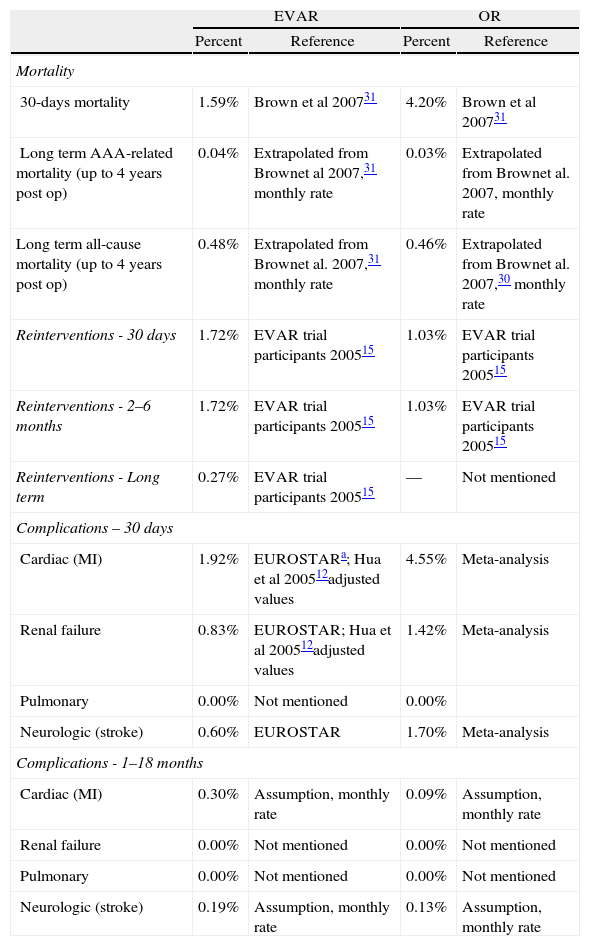

MethodologyWe used an economic evaluation model developed by Abacus International in 2007 and used (adapted for ruptured cases) by Hayes et al.20 This model, developed in Microsoft Excel, includes a decision tree to capture 30-day costs and outcomes, and a Markov model to evaluate long-term costs and health outcomes, from 30 days post-surgery to death. The model assumes two cohorts of 1,000 patients with an average age of 70 years old and treated with EVAR and OR, respectively. Patients are followed over a 30-year period. All details of the model can be found in Hayes et al.20Table 1 summarizes the main health outcomes (we used health consequences from Hayes et al. based on clinical trials) used as inputs for the model and their source. We adopted an actualization rate of 5%, following the Portuguese guidelines for economic evaluation.21

Health outcomes used in the model developed by Abacus International in 2007 and later used (adapted for ruptured cases) by Hayes et al., 2010.

| EVAR | OR | |||

| Percent | Reference | Percent | Reference | |

| Mortality | ||||

| 30-days mortality | 1.59% | Brown et al 200731 | 4.20% | Brown et al 200731 |

| Long term AAA-related mortality (up to 4 years post op) | 0.04% | Extrapolated from Brownet al 2007,31 monthly rate | 0.03% | Extrapolated from Brownet al. 2007, monthly rate |

| Long term all-cause mortality (up to 4 years post op) | 0.48% | Extrapolated from Brownet al. 2007,31 monthly rate | 0.46% | Extrapolated from Brownet al. 2007,30 monthly rate |

| Reinterventions - 30 days | 1.72% | EVAR trial participants 200515 | 1.03% | EVAR trial participants 200515 |

| Reinterventions - 2–6 months | 1.72% | EVAR trial participants 200515 | 1.03% | EVAR trial participants 200515 |

| Reinterventions - Long term | 0.27% | EVAR trial participants 200515 | — | Not mentioned |

| Complications – 30 days | ||||

| Cardiac (MI) | 1.92% | EUROSTARa; Hua et al 200512adjusted values | 4.55% | Meta-analysis |

| Renal failure | 0.83% | EUROSTAR; Hua et al 200512adjusted values | 1.42% | Meta-analysis |

| Pulmonary | 0.00% | Not mentioned | 0.00% | |

| Neurologic (stroke) | 0.60% | EUROSTAR | 1.70% | Meta-analysis |

| Complications - 1–18 months | ||||

| Cardiac (MI) | 0.30% | Assumption, monthly rate | 0.09% | Assumption, monthly rate |

| Renal failure | 0.00% | Not mentioned | 0.00% | Not mentioned |

| Pulmonary | 0.00% | Not mentioned | 0.00% | Not mentioned |

| Neurologic (stroke) | 0.19% | Assumption, monthly rate | 0.13% | Assumption, monthly rate |

For the resource used we considered all direct costs for Portugal associated with treatment of AAA by EVAR and OR. We included all costs related to surgical procedures and in-patient stay, including drugs, diagnostic exams, and bed days; all costs associated with follow-up, re-interventions, and complications over an 18-month time horizon. Regarding the follow-up period, we considered only in-patient care, since ambulatory care costs are negligible compared to those of hospitalization. Nevertheless, we included all drug costs prescribed at the hospital, even if the patient had to acquire them at a community pharmacy.

To measure resources we carried out an expert panel analysis using the modified Delphi technique with two rounds. The questionnaire (based on the Hayes et al. model, 2010)20 included questions related to resource use items mentioned above, and also some questions about clinical outcomes (re-interventions, complications, and mortality) in order to validate for Portugal outcomes obtained in the international literature and to obtain some information about health outcomes. The use of a modified Delphi method was necessary as no observational data were available for Portugal. The first round consisted of a meeting with all experts in which the study and questionnaire were presented, which was then filled in by each expert independently. The research team then compiled the answers and performed a statistical analysis, whose anonymous results were sent to experts for review (second round).

The choice of experts was performed as follows. We accessed the database of all in-patient stays at NHS hospitals during the year 2010.21,22 Based on this information, we chose the seven hospitals with the greatest number of EVAR and OR interventions for the period, in order to have an uneven number of experts and sufficient geographic and practice representation. One of these hospitals was unable to participate in the study due to logistic constraints, so we selected the hospital with the next highest number of EVAR and OR interventions over the period. These hospitals represent up to 88.8% (168) of the total 189 EVAR performed during the year 2010 at NHS hospitals in Portugal, and 74.4% (119) of the 160 OR interventions. One response was not returned in time despite several reminders, and we were thus able to include only six hospitals, which represented in 2010 73.5% and 70.0% of EVAR and OR procedures, respectively.

In order to value resource use associated with treatment of AAA by EVAR and OR, we used several Portuguese national sources. We used the “Catalogue of Health Public Procurement” (Catálogo de Aprovisionamento Público da Saúde) to assign unit costs to drugs.23 Official tariffs from the Ministry of Health were used to obtain unit costs of blood products,24 diagnostic tests, and in-patient stays except for primary intervention.25 We used the average official salary tables for civil servants to assign costs for human resources.26 Finally, we used 2009 accounting data from Portuguese NHS hospitals to assign unit costs to medical visits and operating rooms.27 To assign the unit cost for the contrast agent and the graft used in OR, we contacted individually the manufacturers with the highest market shares in Portugal and used the average of the prices we received. Finally, regarding the unit cost of the endograft used in EVAR, we considered the average price of the Medtronic endograft for Portugal in 2012, following the Hayes et al. study.

Total costs were obtained by multiplying unit cost by the resource use.

ConsequencesThe type of complications (cardiac, renal, pulmonary, and neurological) included in this analysis corresponds to the model developed by Hayes et al.20 The probability of occurrence of events, including death, are also those used by Hayes et al.,20 obtained from randomized clinical trials.

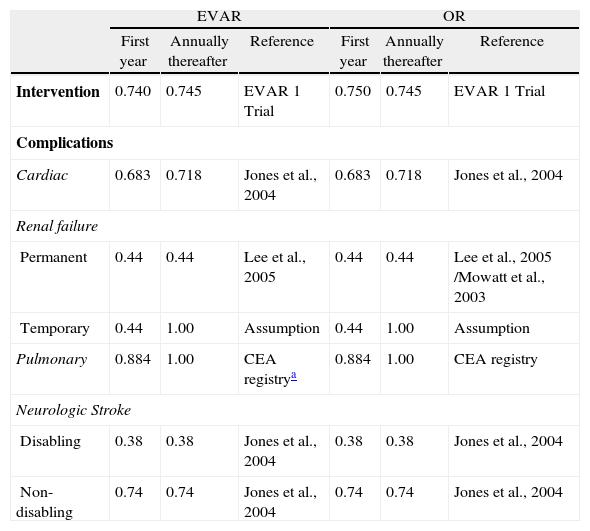

Sensitivity analysisUtilities used in the model are shown in Table 2. A one-way deterministic sensitivity analysis was performed to explore the impact of uncertainties in the model inputs on the cost-effectiveness. For consequences we used as lower and upper values the 95% confidence interval bounds from clinical studies. For costs we assumed 50% up and down variations for all inputs. This assumption is above the usual practice (30%), but we considered it to be more appropriate to test the robustness of our findings, given that our cost data were collected through expert panel survey instead of observational studies.

Utilities for EVAR and OR in the first year and annually thereafter.

| EVAR | OR | |||||

| First year | Annually thereafter | Reference | First year | Annually thereafter | Reference | |

| Intervention | 0.740 | 0.745 | EVAR 1 Trial | 0.750 | 0.745 | EVAR 1 Trial |

| Complications | ||||||

| Cardiac | 0.683 | 0.718 | Jones et al., 2004 | 0.683 | 0.718 | Jones et al., 2004 |

| Renal failure | ||||||

| Permanent | 0.44 | 0.44 | Lee et al., 2005 | 0.44 | 0.44 | Lee et al., 2005 /Mowatt et al., 2003 |

| Temporary | 0.44 | 1.00 | Assumption | 0.44 | 1.00 | Assumption |

| Pulmonary | 0.884 | 1.00 | CEA registrya | 0.884 | 1.00 | CEA registry |

| Neurologic Stroke | ||||||

| Disabling | 0.38 | 0.38 | Jones et al., 2004 | 0.38 | 0.38 | Jones et al., 2004 |

| Non-disabling | 0.74 | 0.74 | Jones et al., 2004 | 0.74 | 0.74 | Jones et al., 2004 |

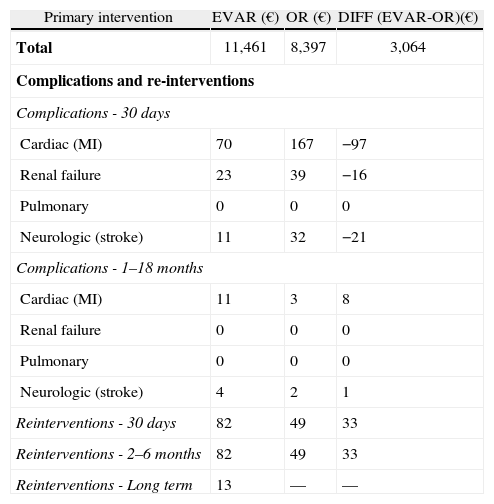

Table 3 shows the comparison of total costs of primary intervention, complications, and re-interventions of EVAR and OR. In the primary intervention we included all relevant cost items such as staff time, blood products, number of days in ICU, LOS, drugs, and diagnostic tests.

Cost of primary intervention, complications and reinterventions for EVAR and OR.

| Primary intervention | EVAR (€) | OR (€) | DIFF (EVAR-OR)(€) |

| Total | 11,461 | 8,397 | 3,064 |

| Complications and re-interventions | |||

| Complications - 30 days | |||

| Cardiac (MI) | 70 | 167 | −97 |

| Renal failure | 23 | 39 | −16 |

| Pulmonary | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Neurologic (stroke) | 11 | 32 | −21 |

| Complications - 1–18 months | |||

| Cardiac (MI) | 11 | 3 | 8 |

| Renal failure | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pulmonary | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Neurologic (stroke) | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Reinterventions - 30 days | 82 | 49 | 33 |

| Reinterventions - 2–6 months | 82 | 49 | 33 |

| Reinterventions - Long term | 13 | — | — |

The major cost difference in the primary intervention (difference of 3,064€ in favor of OR) is related to the cost of the endograft/graft (8,027 € versus 968 €). For the complications and re-interventions, differences are negligible.

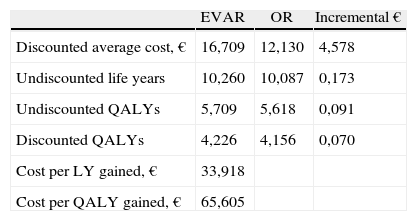

Main results from the cost-effectiveness analysis are in Table 4. Over a 30-year time horizon patients treated with EVAR have a mean undiscounted life expectancy of 10,260 years, and 10,087 years for those treated with OR. Treatment with EVAR thus results in incremental life expectancy of 0,173 life years, which corresponds approximately to one and a half months. The mean undiscounted quality-adjusted life year expectancy (QALY) is 5,709 for EVAR and 5,618 for OR. Discounted values are 4,226 and 4,156 QALYs, respectively.

Results from cost-effectiveness analysis — Base case.

| EVAR | OR | Incremental € | |

| Discounted average cost, € | 16,709 | 12,130 | 4,578 |

| Undiscounted life years | 10,260 | 10,087 | 0,173 |

| Undiscounted QALYs | 5,709 | 5,618 | 0,091 |

| Discounted QALYs | 4,226 | 4,156 | 0,070 |

| Cost per LY gained, € | 33,918 | ||

| Cost per QALY gained, € | 65,605 |

Patients treated with EVAR have 16,709€ mean cost, and 12,130€ for OR patients, resulting in an incremental cost of 4,578€. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio is 33,918€ per life year gained and 65,605€ per QALY gained, using discounted cost and consequences.

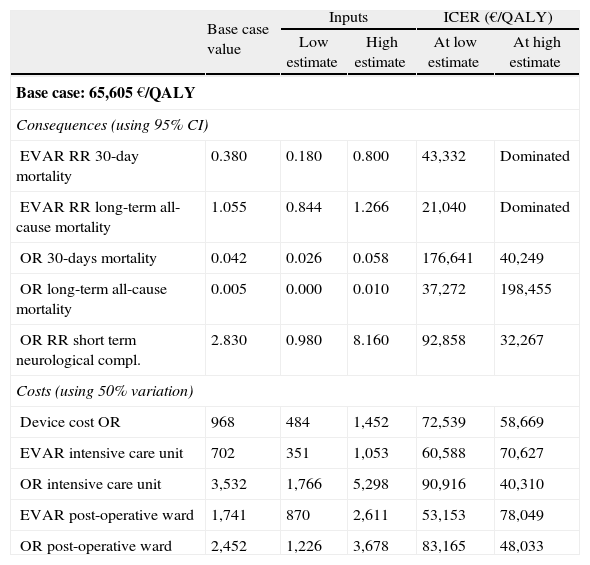

Results from the deterministic sensitivity analysis are presented in Table 5. We show data only for the consequences and costs that most alter the incre mental costeffectiveness ratio. EVAR is dominated when short and long-term mortality risk ratios are less favorable. In the contrary case, the ICER falls well below 50,000€/QALY, and even below 30,000€/QALY in the favorable long-term mortality scenario.

Results from one-way deterministic sensitivity analysis.

| Base case value | Inputs | ICER (€/QALY) | |||

| Low estimate | High estimate | At low estimate | At high estimate | ||

| Base case: 65,605 €/QALY | |||||

| Consequences (using 95% CI) | |||||

| EVAR RR 30-day mortality | 0.380 | 0.180 | 0.800 | 43,332 | Dominated |

| EVAR RR long-term all-cause mortality | 1.055 | 0.844 | 1.266 | 21,040 | Dominated |

| OR 30-days mortality | 0.042 | 0.026 | 0.058 | 176,641 | 40,249 |

| OR long-term all-cause mortality | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.010 | 37,272 | 198,455 |

| OR RR short term neurological compl. | 2.830 | 0.980 | 8.160 | 92,858 | 32,267 |

| Costs (using 50% variation) | |||||

| Device cost OR | 968 | 484 | 1,452 | 72,539 | 58,669 |

| EVAR intensive care unit | 702 | 351 | 1,053 | 60,588 | 70,627 |

| OR intensive care unit | 3,532 | 1,766 | 5,298 | 90,916 | 40,310 |

| EVAR post-operative ward | 1,741 | 870 | 2,611 | 53,153 | 78,049 |

| OR post-operative ward | 2,452 | 1,226 | 3,678 | 83,165 | 48,033 |

The ICER also becomes more favorable to EVAR when we artificially increase the costs of OR stays in intensive care and post-operative units, although values remain above 30,000€/QALY. The impact of changing the discount factor and mean age at intervention is marginal.

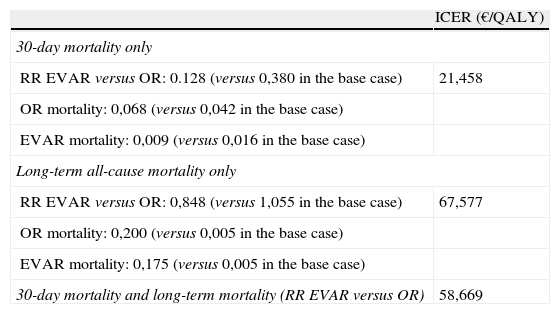

Finally, replacing outcomes from clinical trials with those mentioned by the expert panel survey does not alter results significantly, as the cost-effectiveness ratio rises to 58,669€/QALY (Table 6). Results improve dramatically if we consider only the panel's outcome for 30-day mortality (21,458 €/QALY) but worsen if we consider the panel's outcomes for long-term mortality (67,577 €/QALY). The difference in the relative risk of 30-day mortality (0,128 versus 0,380) certainly explains the first result, combined with the lower mortality from OR (6.8% versus 4.2%) and lower mortality from EVAR (0.9% versus 1.7%).

Results using consequences obtained from the expert panel survey.

| ICER (€/QALY) | |

| 30-day mortality only | |

| RR EVAR versus OR: 0.128 (versus 0,380 in the base case) | 21,458 |

| OR mortality: 0,068 (versus 0,042 in the base case) | |

| EVAR mortality: 0,009 (versus 0,016 in the base case) | |

| Long-term all-cause mortality only | |

| RR EVAR versus OR: 0,848 (versus 1,055 in the base case) | 67,577 |

| OR mortality: 0,200 (versus 0,005 in the base case) | |

| EVAR mortality: 0,175 (versus 0,005 in the base case) | |

| 30-day mortality and long-term mortality (RR EVAR versus OR) | 58,669 |

There is a consensus that EVAR significantly reduces short-term mortality, resulting in an early survival advantage. Also, EVAR is a less invasive procedure as compared to conventional OR, leading to fewer post-operative complications, faster recovery, and shorter hospital stays.

An unquestionable advantage of the EVAR is also in the treatment of certain sub-groups of patients who previously had no treatment option, with consequent health gains.28 However, some concerns remain regarding the long-term results of EVAR, namely its increased need for re-interventions and its benefits on long-term survival In addition, the incremental cost of EVAR raises questions about the economic value of this intervention.16,29-31

This study examines the cost-effectiveness of EVAR as compared to OR to treat abdominal aortic aneurysm from the NHS perspective.

In general, findings are in line with earlier literature showing that EVAR represents additional costs as compared to OR, but provides additional benefits in life expectancy and quality of life.2,7,11,29 These benefits are concentrated in the short/mid-term (up to 2 years) period after intervention. Based on this study, the value of EVAR is of 65,605€/QALY, which is above the commonly accepted cost-effectiveness threshold in Portugal (although no official threshold exists, “informal” evidence suggests a value of 30,000€/QALY). However, this value gets close to 30,000€/QALY when we assume that EVAR benefits are extended to the long term. In this sense, Quinney et al.,10 and Jackson et al.14 recently found a survival advantage of EVAR after 100 months and at five years of follow-up, respectively. These new findings suggest an improved benefit of endovascular repair over time.

Finally, the cost-effectiveness ratio is not altered as we replace outcomes mentioned in clinical trials with those mentioned by our panel of Portuguese specialists (58,669 €/ QALY). However, outcomes become highly favorable to EVAR as we consider the panel's outcome for 30-day mortality (21,458 €/QALY). This result must be interpreted with caution. On the one hand, a survey of a restricted number of experts is certainly not as reliable as outcomes from randomized clinical trials.32 On the other hand, clinical trials are performed in a very specific context that may not apply in real conditions, subject to differences in practices, adherence to treatment or budget constraints, among others.32 We also cannot ignore the possibility that Portuguese practices produce different clinical outcomes compared to those obtained in other countries. To conclude, although clinical outcomes in Portugal would require validation using more accurate data (for instance, from observational studies; RCTs, and National Registries), cost-effectiveness ratios based on available clinical information for Portugal are quite favorable, and confirm the promising value of EVAR.

This study suffers from the usual limitations of modelbased economic evaluations, namely the impos sibility to observe long-term effects, which are instead estimated based on available data and assumptions. This is inevitable as we seek to support decisions in the short term based on available information. Also, clinical effects in the base model are based on data from the literature and not on observational data for Portugal. However, these data are based on large clinical trials whose results have been published in reputable international scientific journals, and we have no reason to believe the impact of interventions would differ in Portugal as compared to other industrialized countries. Third, cost data were obtained from an expert panel survey, which is certainly less reliable than systematic observational data based e.g. on clinical records. However, this technique is widely used in economic evaluation, and our results are found to be highly robust to large changes (50%) in cost values. Moreover, the modified Delphi technique is commonly performed and accepted in the economic evaluation literature,33 in the definition of therapeutic guidelines,34 and to measure clinical practice.35

Finally, we were not able to distinguish different population sub-groups. The York Report of economic evaluation (2009) considers that EVAR is likely to be cost-effective in patients with high operative risk and in patients with small aneurysms. It is also considered that the cost-effectiveness of EVAR may be sensitive to the patient's age and fitness at intervention.36 The recent NICE technology appraisal guidance (2009) reviewed in 2012, considers that EVAR is likely to be cost-effective for patients of moderate fitness and with large aneurysms (>7.5cm) aged 80 years and older, and for patients with poor fitness, aged 75 years and older with aneurysm size between 5.5 cm and 6.0 cm.37 Further research using Portuguese data should consider these aspects.

Finally, Portuguese data from all NHS hospitals indicate that patients treated with OR are more likely to be admitted to nursing homes than patients treated with EVAR (5.6% versus 10.8%), confirming recent results from the literature.19,38 The consequences of this difference were not included in our study as no reliable data were available about the additional cost of these stays at nursing homes, leading to an underestimation of the value of EVAR. Indeed, this would require estimating their length and daily price, which is not a trivial issue as those services are mostly provided privately in Portugal (there are no official fees and prices differ across patients and facilities). More generally, we could not account in our study for the out-of-hospital costs borne by the patient and the State, which include nursing homes and primary care, drugs bought at community pharmacies, social services, and family support.

ConclusionThe highly indebted of the Portuguese National Health Service emphasizes the need to guarantee universal coverage and high quality of care at a sustainable cost. Economic evaluations of health care interventions represent a valuable instrument to help decision-makers adopt the strategies that bring greater benefits at lower costs - value for money. One of the main points that come up indirectly from this study is that we need more robust data for Portugal, mainly from observational studies, clinical registries and about costs. Endovascular repair of aortic abdominal aneurysm seems to represent an effective alternative and has been used increasingly in Portugal and elsewhere. Our study shows that its costeffectiveness is currently above the commonly accepted threshold in Portugal, but that the economic value of EVAR would greatly improve if benefits were confirmed in the long run following the intervention.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingThis study has received unconditional funding from Medtronic. The interpretation of the data and conclusions of this study are entirely those of the authors.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.