Liver cirrhosis is a major cause of mortality worldwide. Adequate diagnosis and treatment of decompensating events requires of both medical skills and updated technical resources. The objectives of this study were to search the demographic profile of hospitalized cirrhotic patients in a group of Latin American hospitals and the availability of expertise/facilities for the diagnosis and therapy of decompensation episodes.

MethodsA cross sectional, multicenter survey of hospitalized cirrhotic patients.

Results377 patients, (62% males; 58±11 years) (BMI>25, 57%; diabetes 32%) were hospitalized at 65 centers (63 urbans; 57 academically affiliated) in 13 countries on the survey date. Main admission causes were ascites, gastrointestinal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis/other infections. Most prevalent etiologies were alcohol-related (AR) (40%); non-alcoholic-steatohepatitis (NASH) (23%), hepatitis C virus infection (HCV) (7%) and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) (6%). The most frequent concurrent etiologies were AR+NASH. Expertise and resources in every analyzed issue were highly available among participating centers, mostly accomplishing valid guidelines. However, availability of these facilities was significantly higher at institutions located in areas with population>500,000 (n=45) and in those having a higher complexity level (Gastrointestinal, Liver and Internal Medicine Departments at the same hospital (n=22).

ConclusionsThe epidemiological etiologic profile in hospitalized, decompensated cirrhotic patients in Latin America is similar to main contemporary emergent agents worldwide. Medical and technical resources are highly available, mostly at great population urban areas and high complexity medical centers. Main diagnostic and therapeutic approaches accomplish current guidelines recommendations.

Cirrhosis is the end-stage of different etiology-related chronic liver diseases, being alcohol-related (AR), hepatitis C virus infection (HCV) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) the most commonly involved [1,2].

Along its natural history the disease undergoes different progressive stages, either considered as compensated or decompensated [3,4]. The compensated state, usually the longest, is almost devoid of symptoms and therefore, liver disease related hospital admissions are uncommon. On the other hand, almost every event characterizing the decompensated stage requires admission, in order to be properly diagnosed and treated.

Main decompensating events are: esophageal variceal bleeding (EVB), ascites, hepatic encephalopathy (HE) and jaundice. Closely related, either as the cause or as a consequence, infections and hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) are frequently present in decompensated patients [4–7]. Alone or combined, all these complications represent a threatening condition in cirrhotic patients, decreasing their life expectancy [4,8,9]. Moreover, the growing incidence of primary liver cancer, mostly hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), is another determinant of frequent nosocomial admissions [10].

For each of these complications, diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms have been proposed and translated into different valid guidelines [11–16]. The challenging consequence of these recommendations is a permanent requirement of both adequate medical and technical resources at the institutions where these patients are treated. In fact, decompensated cirrhotic patients are mainly admitted to Gastroenterology or Int Med Depts, as Liver Units are usually restricted to specific referral centers, mostly located at great urban areas. Given the diversity of institutions involved, a potential lack of homogeneity may translate into uneven quality in medical care provided for those decompensating events [17–19].

Therefore, the present study was designed in order to search: (a) the demographic and clinical–epidemiological characteristics of cirrhotic patients hospitalized on certain date at different medical centers of Central and South America and (b) the availability of resources and expertise for diagnosis and treatment of the most frequent complications of liver cirrhosis.

2MethodsA cross-sectional, multicenter, observational study, performed on March 21st, 2018. Every national society affiliated to the Latin American Association for the Study of the Liver (ALEH) and all regional associations subsidiaries of the Argentine Federation of Gastroenterology (FAGE) were invited to partipate. Those accepting provided a list of medical institutions where cirrhotic patients are frequently admitted. Invitations including detailed objectives and design of the study were mailed. Those centers accepting completed the questionaire with data corresponding to the aforementioned date.

The whole survey contained 52 questions, divided in 3 sections: (1) data related to the participating medical center and its location (10 questions), (2) a clinical/demographic profile of every cirrhotic patient remaining hospitalized on March 21st/2018 (13 questions) and (3) an inquiry regarding usual therapeutic attitudes and corresponding available resources for the management of (a) EVB; (b) ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), HRS and non-SBP infections; (c) HE; (d) liver transplantation (LT) and (e) HCC (29 questions).

The investigation was approved by the Human Investigation Committees of participating institutions.

All data were centralized at one center (Gastroenterology and Liver Dept, University of Rosario Medical School, Rosario, Argentina) and assembled and processed by JV, LH and FT.

2.1Statistical analysisContinuous variables are shown as Mean±SD or Median and Range. Categorical variables are shown as relative and absolute frequencies. Associations between categorical variables were analyzed by the Chi-Square test or Fisher's Exact test. Results were considered significant at p values of<0.05 [20,21].

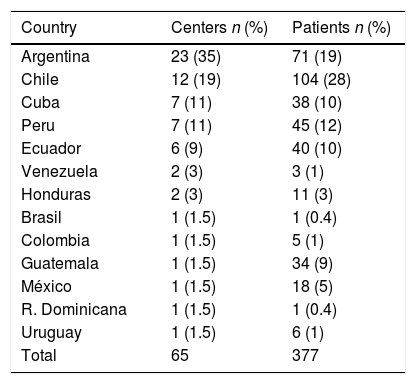

3Results3.1Participating centersOne hundred and seventy five centers from 16 countries were invited to participate. Sixty five (37%) of them, corresponding to 13 countries, completed the survey (Table 1). Sixty three (97%) were located at urban areas, 45 (71%) with populations>500,000 (Table 2). Fifty seven (88%) centers, either public (47) or private (10), were University affiliated. Within 63 institutions, Int Med & Gastroenterology Depts were present at 33 (52%); Int Med, Gastroenterology & Liver Depts at 22 (35%) and only an Int Med Dept at 8 (13%). LT units were available at 16 centers (Supplementary Table 1).

Centers and patient distribution according to participating countries.

| Country | Centers n (%) | Patients n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 23 (35) | 71 (19) |

| Chile | 12 (19) | 104 (28) |

| Cuba | 7 (11) | 38 (10) |

| Peru | 7 (11) | 45 (12) |

| Ecuador | 6 (9) | 40 (10) |

| Venezuela | 2 (3) | 3 (1) |

| Honduras | 2 (3) | 11 (3) |

| Brasil | 1 (1.5) | 1 (0.4) |

| Colombia | 1 (1.5) | 5 (1) |

| Guatemala | 1 (1.5) | 34 (9) |

| México | 1 (1.5) | 18 (5) |

| R. Dominicana | 1 (1.5) | 1 (0.4) |

| Uruguay | 1 (1.5) | 6 (1) |

| Total | 65 | 377 |

Demographic characteristics of included patients.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sex (n=373) | |

| Males | 231 (62%) |

| Females | 142 (38%) |

| Age (years) | |

| <20 | 13 (3%) |

| 21–40 | 36 (10%) |

| 41–60 | 167 (44%) |

| 61–80 | 149 (40%) |

| >80 | 12 (3%) |

| Body weight (kg) (M±SD) (range) | 70±18 (5.6–164) |

| BMI | |

| <18.5 | 19 (5%) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 144 (38%) |

| 25–29.9 | 127 (34%) |

| >30 | 87 (23%) |

| Diabetes | 122 (32%) |

BMI: body mass index.

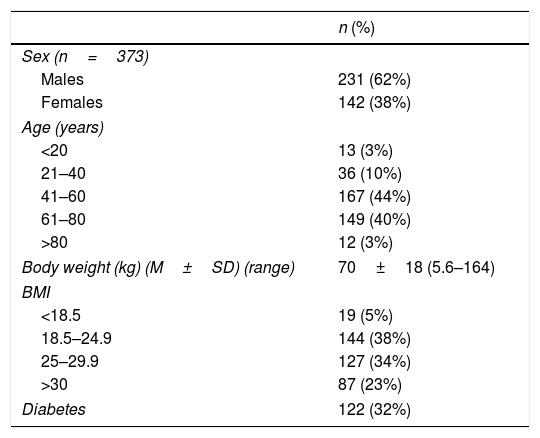

Patients: Three hundred and seventy seven cirrhotic patients were hospitalized on the date of the survey. Gender data was available in 373, of whom 231 (62%) were males. Those between 41 and 80 years accounted for 84% (316) of the population (41–60 and 61–80, 44% (167) and 40% (149); respectively) (NS). Mean body weight of 377 patients was 70±18kg (5.6–164) and the body mass index (BMI) was>25 in 214 (57%). Diabetes was present in 122 (32%) patients (Table 2). Sex distribution among different age ranges was not significantly different (Supplementary Table 2).

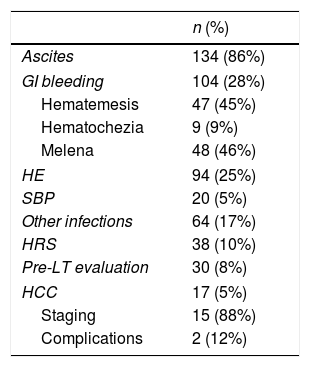

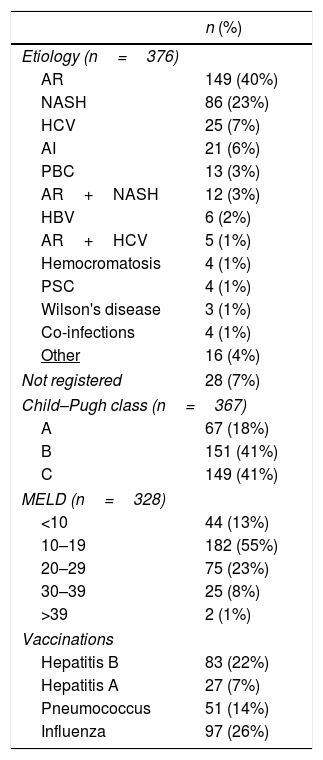

Main identifiable admission causes were: ascites (n=134; 36%), gastrointestinal beeding (GIB) (n=104; 27%), HE (n=94; 24%), SBP/other infections (n=84; 22%) and HRS (n=38; 10%) (Table 3). Within 367 patients, 151 CP class B and 149 CP class C comprised 82% of them. MELD was available in 328 patients, of whom 182 (55%) scored within 10 to 19 and 100 (30%) from 20 to 38 (Table 4).

Main admission causes.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Ascites | 134 (86%) |

| GI bleeding | 104 (28%) |

| Hematemesis | 47 (45%) |

| Hematochezia | 9 (9%) |

| Melena | 48 (46%) |

| HE | 94 (25%) |

| SBP | 20 (5%) |

| Other infections | 64 (17%) |

| HRS | 38 (10%) |

| Pre-LT evaluation | 30 (8%) |

| HCC | 17 (5%) |

| Staging | 15 (88%) |

| Complications | 2 (12%) |

GI: gastrointestinal; HE: hepatic encephalopathy; SBP: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; HRS: hepatorenal syndrome; LT: liver transplantation; HCC; hepatocellular carcinoma.

Clinical characteristics of included patients.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Etiology (n=376) | |

| AR | 149 (40%) |

| NASH | 86 (23%) |

| HCV | 25 (7%) |

| AI | 21 (6%) |

| PBC | 13 (3%) |

| AR+NASH | 12 (3%) |

| HBV | 6 (2%) |

| AR+HCV | 5 (1%) |

| Hemocromatosis | 4 (1%) |

| PSC | 4 (1%) |

| Wilson's disease | 3 (1%) |

| Co-infections | 4 (1%) |

| Other | 16 (4%) |

| Not registered | 28 (7%) |

| Child–Pugh class (n=367) | |

| A | 67 (18%) |

| B | 151 (41%) |

| C | 149 (41%) |

| MELD (n=328) | |

| <10 | 44 (13%) |

| 10–19 | 182 (55%) |

| 20–29 | 75 (23%) |

| 30–39 | 25 (8%) |

| >39 | 2 (1%) |

| Vaccinations | |

| Hepatitis B | 83 (22%) |

| Hepatitis A | 27 (7%) |

| Pneumococcus | 51 (14%) |

| Influenza | 97 (26%) |

AR: alcohol related; NASH: non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; HCV: hepatitis C virus; AI: autoimmune hepatitis; PBC; primary biliary cholangitis; HBV: hepatitis B virus; PSC; primary sclerosing cholangitis; CP class: Child–Pugh class; MELD: Model for End-Stage Liver Disease.

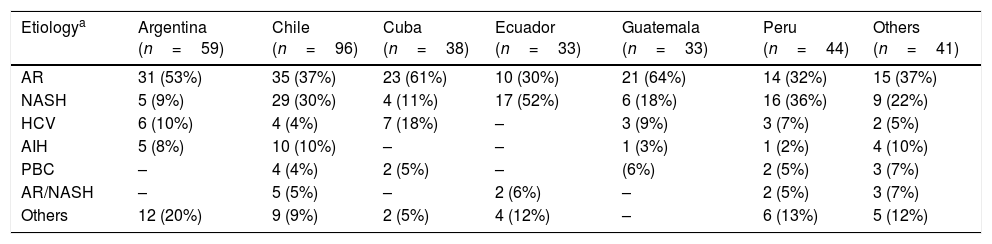

AR (40%); NASH (23%), HCV infection (7%) and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) (6%) were the most prevalent etiologies being AR+NASH the most common concurrent etiology (Table 4). Liver disease etiology, according to gender distribution, showed significant differences, being NASH, HCV, AIH and PBC more prevalent in females and AR among men (Supplementary Table 3). No significant difference related to etiology was observed when comparing countries recruiting more than 30 patients versus all others. However, NASH resulted highly prevalent within patients enrolled in the Pacific coast (Chile, Perú and Ecuador) (Table 5).

Etiology distribution in participating countries.

| Etiologya | Argentina (n=59) | Chile (n=96) | Cuba (n=38) | Ecuador (n=33) | Guatemala (n=33) | Peru (n=44) | Others (n=41) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR | 31 (53%) | 35 (37%) | 23 (61%) | 10 (30%) | 21 (64%) | 14 (32%) | 15 (37%) |

| NASH | 5 (9%) | 29 (30%) | 4 (11%) | 17 (52%) | 6 (18%) | 16 (36%) | 9 (22%) |

| HCV | 6 (10%) | 4 (4%) | 7 (18%) | – | 3 (9%) | 3 (7%) | 2 (5%) |

| AIH | 5 (8%) | 10 (10%) | – | – | 1 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 4 (10%) |

| PBC | – | 4 (4%) | 2 (5%) | – | (6%) | 2 (5%) | 3 (7%) |

| AR/NASH | – | 5 (5%) | – | 2 (6%) | – | 2 (5%) | 3 (7%) |

| Others | 12 (20%) | 9 (9%) | 2 (5%) | 4 (12%) | – | 6 (13%) | 5 (12%) |

AR: alcohol-related; NASH: non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; HCV: hepatitis C virus; AIH: autoimmune hepatitis; PBC: primary biliary cholangitis; AR/NASH; alcohol-related/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

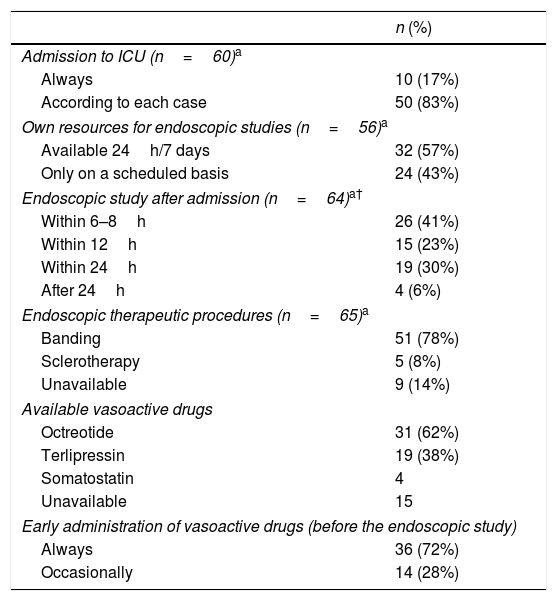

Bleeders are always admitted to the ICU at 10 (17%) centers while most others (50; 83%) consider ICU indication on an individual basis. Endoscopy is available on a 24h/7 days basis in 32/56 (57%) centers and studies are performed within 12h after admission in 41/56 (73%). Banding is the preferred therapeutic choice. Among 50 institutions, Octreotide and Terlipressin are the most utilized vasoactive drugs and are always administered before the endoscopic study in 36 (72%) of them (Table 6). ATB are administered since admission in 52 (80%) centers, being ceftriaxone the most utilized. Regarding the SBT 39 (60%) centers use it only when all other therapeutic measures fail. The tube is not available at 21 (32%) institutions while it is the only available therapeutic tool at 5 (8%). Eight centers (12%) can offer TIPS in the emergency setting while self-expandable metal stents are available at 11 (17%) institutions (Supplementary Table 4).

Management of variceal bleeding.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Admission to ICU (n=60)a | |

| Always | 10 (17%) |

| According to each case | 50 (83%) |

| Own resources for endoscopic studies (n=56)a | |

| Available 24h/7 days | 32 (57%) |

| Only on a scheduled basis | 24 (43%) |

| Endoscopic study after admission (n=64)a† | |

| Within 6–8h | 26 (41%) |

| Within 12h | 15 (23%) |

| Within 24h | 19 (30%) |

| After 24h | 4 (6%) |

| Endoscopic therapeutic procedures (n=65)a | |

| Banding | 51 (78%) |

| Sclerotherapy | 5 (8%) |

| Unavailable | 9 (14%) |

| Available vasoactive drugs | |

| Octreotide | 31 (62%) |

| Terlipressin | 19 (38%) |

| Somatostatin | 4 |

| Unavailable | 15 |

| Early administration of vasoactive drugs (before the endoscopic study) | |

| Always | 36 (72%) |

| Occasionally | 14 (28%) |

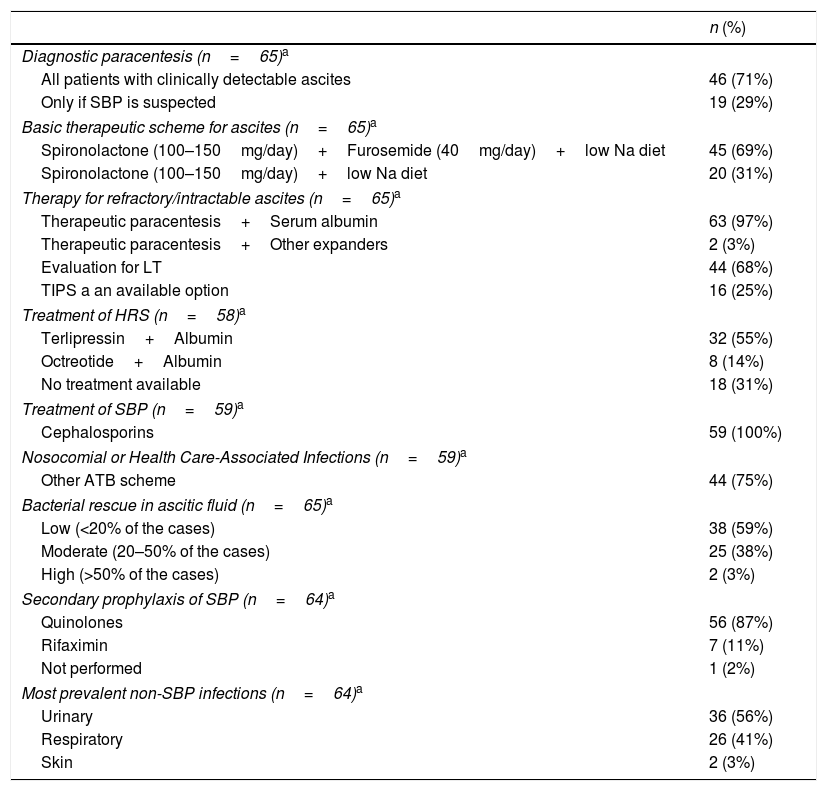

Management of ascites, SBP, HRS and infections: Diagnostic paracentesis is mandatory in 46 (71%) centers while in other 19 (29%) is performed only when SBP is suspected. The basic therapeutic approach includes spironolactone (100–150mg/day) plus furosemide (40mg/day) plus low Na diet or only spironolactone (100–150mg/day) plus low Na diet in 45 (69%) and 20 (31%) institutions, respectively. Intractable/refractory ascites is treated with paracentesis plus serum albumin in 63 (97%) institutions and is considered a criterion for LT evaluation in 44 (68%) centers. HRS is treated with terlipressin plus serum albumin in 32 (55%) centers while 8 (14%) others utilize octreotide plus serum albumin (p<0.01) (Table 7). Among 59 responders, SBP is routinely treated with cephalosporins while in nosocomial or health care-associated infections another ATB scheme is utilized. Bacterial rescue in ascitic fluid is low: <20% in 38 (59%) centers. Secondary prophylaxis of SBP is managed with quinolones in most centers. Urinary and respiratory are the most prevalent non-SBP infections (Table 7).

Management of ascites, SBP, HRS and infections.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Diagnostic paracentesis (n=65)a | |

| All patients with clinically detectable ascites | 46 (71%) |

| Only if SBP is suspected | 19 (29%) |

| Basic therapeutic scheme for ascites (n=65)a | |

| Spironolactone (100–150mg/day)+Furosemide (40mg/day)+low Na diet | 45 (69%) |

| Spironolactone (100–150mg/day)+low Na diet | 20 (31%) |

| Therapy for refractory/intractable ascites (n=65)a | |

| Therapeutic paracentesis+Serum albumin | 63 (97%) |

| Therapeutic paracentesis+Other expanders | 2 (3%) |

| Evaluation for LT | 44 (68%) |

| TIPS a an available option | 16 (25%) |

| Treatment of HRS (n=58)a | |

| Terlipressin+Albumin | 32 (55%) |

| Octreotide+Albumin | 8 (14%) |

| No treatment available | 18 (31%) |

| Treatment of SBP (n=59)a | |

| Cephalosporins | 59 (100%) |

| Nosocomial or Health Care-Associated Infections (n=59)a | |

| Other ATB scheme | 44 (75%) |

| Bacterial rescue in ascitic fluid (n=65)a | |

| Low (<20% of the cases) | 38 (59%) |

| Moderate (20–50% of the cases) | 25 (38%) |

| High (>50% of the cases) | 2 (3%) |

| Secondary prophylaxis of SBP (n=64)a | |

| Quinolones | 56 (87%) |

| Rifaximin | 7 (11%) |

| Not performed | 1 (2%) |

| Most prevalent non-SBP infections (n=64)a | |

| Urinary | 36 (56%) |

| Respiratory | 26 (41%) |

| Skin | 2 (3%) |

ATB: antibiotics; SBP: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; LT: liver transplantation; TIPS: transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt; HRS: hepatorenal syndrome.

HE was focused on 2 different scenarios: a) prevention during the acute bleeding episode, which is performed at 58 (89%) institutions, 33 (51%) of which utilize Lactulose and b) chronic HE, which is mostly treated with Lactulose plus Rifaximine, also at 33 (51%) centers (Supplementary Table 5).

3.4Liver transplantationLT is available at 21 (32%) institutions, 8 of them performing more than 20 transplants per year. Within 20 of these centers, the most prevalent etiologies in transplanted patients are NASH in 9 (45%), AR in 6 (30%) and HCV in 5 (25%) (Supplementary Table 6).

3.5Screening and management of HCCAn US plus alpha-pheto protein or an US (every 6 months in both cases) are the standard screening methods in 43 (69%) and 18 (29%) centers; respectively. The most available therapeutic modalities are surgery and transarterial chemoembolization (23 institutions) (Suplementary Table 7).

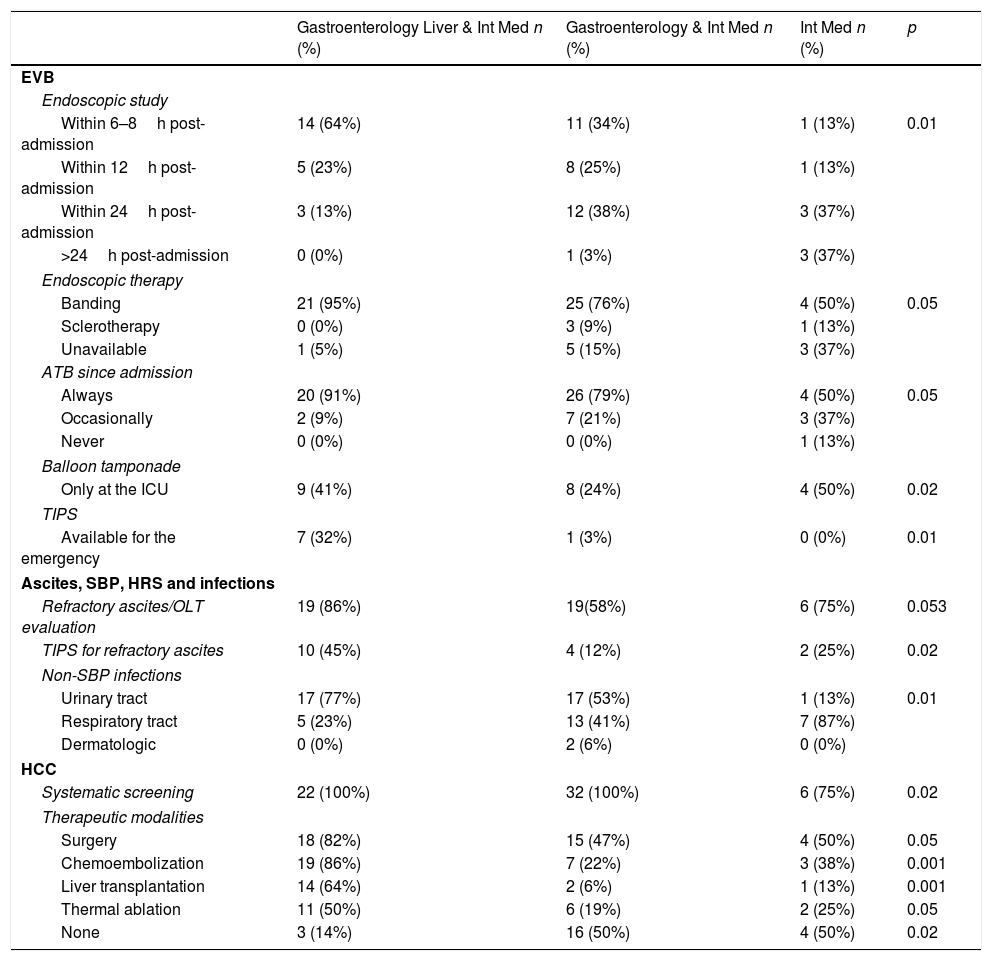

Resources and therapeutic modalities according to center affiliation, complexity and location:

Several differences related to therapeutic attitudes and resources were observed among centers, related to hospital complexity (Int Med & Liver & Gastroenterology Depts., Int Med & Gastroenterology Depts. or only an Int Med Dept) and population at its location (< or >500,000). Among university affiliated/non-affiliated centers the only significant difference was related to the treatment of intractable/refractory ascites for which therapeutic paracentesis plus serum albumin is more frequently used in affiliated ones (p<0.01). Differences according to institution complexity and area population are depited in Table 8 and Supplementary Tables 8 and 9; respectively.

Major differences according to hospital complexity.

| Gastroenterology Liver & Int Med n (%) | Gastroenterology & Int Med n (%) | Int Med n (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVB | ||||

| Endoscopic study | ||||

| Within 6–8h post-admission | 14 (64%) | 11 (34%) | 1 (13%) | 0.01 |

| Within 12h post-admission | 5 (23%) | 8 (25%) | 1 (13%) | |

| Within 24h post-admission | 3 (13%) | 12 (38%) | 3 (37%) | |

| >24h post-admission | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 3 (37%) | |

| Endoscopic therapy | ||||

| Banding | 21 (95%) | 25 (76%) | 4 (50%) | 0.05 |

| Sclerotherapy | 0 (0%) | 3 (9%) | 1 (13%) | |

| Unavailable | 1 (5%) | 5 (15%) | 3 (37%) | |

| ATB since admission | ||||

| Always | 20 (91%) | 26 (79%) | 4 (50%) | 0.05 |

| Occasionally | 2 (9%) | 7 (21%) | 3 (37%) | |

| Never | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (13%) | |

| Balloon tamponade | ||||

| Only at the ICU | 9 (41%) | 8 (24%) | 4 (50%) | 0.02 |

| TIPS | ||||

| Available for the emergency | 7 (32%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.01 |

| Ascites, SBP, HRS and infections | ||||

| Refractory ascites/OLT evaluation | 19 (86%) | 19(58%) | 6 (75%) | 0.053 |

| TIPS for refractory ascites | 10 (45%) | 4 (12%) | 2 (25%) | 0.02 |

| Non-SBP infections | ||||

| Urinary tract | 17 (77%) | 17 (53%) | 1 (13%) | 0.01 |

| Respiratory tract | 5 (23%) | 13 (41%) | 7 (87%) | |

| Dermatologic | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| HCC | ||||

| Systematic screening | 22 (100%) | 32 (100%) | 6 (75%) | 0.02 |

| Therapeutic modalities | ||||

| Surgery | 18 (82%) | 15 (47%) | 4 (50%) | 0.05 |

| Chemoembolization | 19 (86%) | 7 (22%) | 3 (38%) | 0.001 |

| Liver transplantation | 14 (64%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (13%) | 0.001 |

| Thermal ablation | 11 (50%) | 6 (19%) | 2 (25%) | 0.05 |

| None | 3 (14%) | 16 (50%) | 4 (50%) | 0.02 |

EVB: esophageal variceal bleeding; ATB: antibiotics; TIPS: transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt; SBP: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; HRS: hepatorenal syndrome; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma.

Cirrhosis is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide [1,2,22–24]. Regardless of successful preventive measures and specific therapies for certain etiologies [25–27], the growing incidence of other agents as main determinants of chronic liver injury sustains its prevalence [2,28]. Advanced cirrhotic patients face the risk of decompensation that, once present, requires frequent hospital admissions [5–7,29–32]. In order to diagnose and treat them adequately, they should take place at centers where both medical know-how and updated technical resources are available. However, this is not always feasible, and patients may be admitted at institutions lacking expertise for their management [17–19].

The present survey, the first of its kind performed in Latin America, analyses data obtained from a group of mostly urban located centers, sharing a high degree of academic affiliation. The existence of Gastroenterology Depts at most of them, frequently associated to Liver Units, explain the significant presence of decompensated cirrhotic patients at these institutions.

The final data includes 13 (81%) of 16 originally invited countries, with a global answer rate of 37%. The contribution was quite heterogeneous, showing, in some specific cases, a disproportion between country population and the number of participating centers. Therefore, 53% of the countries recruited 85% of the centers providing 93% of included patients. Given this limited territorial projection, representative value of these data may be questioned. However, as mentioned before, no significant difference was observed between those patients recruited at major contributing countries (>30 pts) versus those included at less contributors.

AR was the global leading cause. However, as previously mentioned, NASH resulted highly prevalent within patients enrolled in the Pacific coast (Chile, Perú and Ecuador). In spite of this, BMI categories and diabetes incidence did not differ between these 3 countries and the others (not shown in Results). Reasons for this distinctive feature remain unknown as neither etnicity nor dietary habits were part of the inquiry.

Male predominance, a treshold age of 40 years for the majority and both CP/MELD scores reflecting advanced disease characterized this population. Interestingly, a BMI>25 and diabetes were present in 57% (n=214) and 32% (n=122) of them, respectively. AR and NASH were the most prevalent etiologies, both accounting for 63% (n=235) of the population while HCV, the third related cause, represented 7% (n=25) of the cases. This profile is coincident with reports showing a shift toward AR and NASH as the main contemporary emergent agents of chronic liver disease [1,2,23,24,28,33,34]. Interestingly, HCV infection was higher in females, as has been previously reported in specific Latin American geographic areas [35] (Supplementary Table 3).

Remarkably, a low vaccination rate was observed in these patients, far away from recommended schedules for cirrhotic patients [36].

Sign and symptom overlap (i.e. GIB/HE, infections/HRS) is frequent in decompensated cirrhotics, making identification of a single admission cause occasionally difficult. Therefore, given the high frequency of such combinations, admission cause was defined as the prevailing feature at presentation (“main admission cause”). Accordingly, ascites, GIB, HE and infections were the main identifiable admission causes, as reported elsewhere [7,32,37,38].

Regarding EVB, recommended steps are adequately followed at most institutions [11]. Nevertheless, some disparities deserve comment. Bleeders are “always” admitted to ICUs at only 20% of these institutions. According to the Baveno VI consensus meeting “patients with acute variceal hemorrhage should be considered for ICU or other well-monitored units” [11]. Although desirable, wether most centers not admitting bleeders to ICUs are doing it at “other well-monitored units” is difficult to assume. Vasoactive drugs and ATB administration associated to diagnostic/therapeutic endoscopic procedures performance was homogeneously qualified among all centers. A remarkable point is the unavailability of a SBT at 32% (n=21) of the places while, on the other hand, SBT is the only available therapeutic tool at 5 of them. May this implie its under or over usage is hipothetical. However, given the limited availability of both emergency TIPS (8 centers; 12%) and self-expandable metal stents (11 centers; 17%), possession of a SBT must be strongly encouraged.

Ascites therapy is a well standardized issue [13,19], however, care of these patients may be suboptimal [18]. The fact that in the present survey diagnostic paracentesis is performed “only” when SBP is suspected in almost 30% of the centers is worrisome, as SBP may be absolutely asymptomatic. Moreover, its suspicion is not the only indication to perform a diagnostic paracentesis [13,39,40]. This criterion must be necessarily reconsidered. Both standard medical treatment of ascites and therapy at its refractory status were homogeneously satisfactory, endorsing guidelines recommendations [13,40,41]. On the other hand, 1 every 3 centers lacks an adequate treatment for HRS. Finally, regarding SBP, a delicate problem is the low bacterial rescue in ascitic fluid in almost 60% of the institutions, well below reported standard results [41,42]. Inadequate sample collection and/or lack of updated culture technology may explain these dissapointing results.

Prevention of HE either during the acute bleeding episode or as therapy of its chronic stage is accomplished in most centers [15]. Regarding LT, it is available at 32% (n=21) of participating hospitals endorsing the assertion that referral centers were highly represented at this survey. Moreover, liver disease etiology of transplanted patients shows the same changing trend actually observed in the United States [43–45].

Remarkably, HCC screening is performed at 95% (n=62) of the institutions. This elevated screening index is also mirroring a group of mostly liver disease devoted institutions, overcoming suboptimal surveillance observed in non-liver disease oriented centers [46,47]. Nevertheless, a mix of different treatment proposals is only available at 33 of the centers. Finally, medical skills, updated technology and a higher level of adherence to guidelines recommendations prevailed in centers located at the most populated areas (>500,000) as well as in those having simultaneous Gastroenterolgy, Liver and Int Med Depts.

A weakness of this study may be its representative value. Nevertheless, in this group of mainly urban located centers, patient characteristics were homogeneous, regardless number included and countries considered. Therefore, we believe the results are confident enough to accomplish the survey objectives. It may also be argued that Acute on Chronic Liver Disease (ACLF) was not considered among admission causes. In fact, proposal of ACLF as a late decompensation event appeared on a subsequent date of this survey development [4]. Additionally, the survey may be qualified as biased, not acknowledging the “real world”. In fact it is so. As mentioned, medical care of decompensated cirrhotic patients requires a degree of complexity not available anywhere, but at referral centers, to which this survey was intentionally addressed.

In conclusion, this study updates the current status of capacities aimed at the medical care of decompensated cirrhotic patients in a group of Latin American medical centers. Notwithstanding its limited representation, it shows a high degree of resources availability, mostly according with current guidelines recommendations. Several facilities are available, mainly at referral centers, thereby providing the coordinated and multidisciplinary interventions required for the adequate treatment of these patients [18,19,48].AbbreviationsAIH autoimmune hepatitis alcohol-related antibiotics body mass index departments Child–Pugh esophageal variceal bleeding gastro-intestinal bleeding hepatocellular carcinoma hepatitis C virus hepatic encephalopathy hepatorenal syndrome Intensive Care Unit internal medicine liver transplant Model for End-stage Liver Disease non-alcoholic steatohepatitis primary biliary cholangitis spontaneous bacterial peritonitis Sengstaken-Blakemore tube transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt ultrasound

No financial support specific for this study was received.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest that pertain to this work.

A special recognition to ALEH and FAGE for their institutional and administrative support. The authors are indebted to Professor Roberto Groszmann, M.D. for his generous assistance.