Hepatitis virus and alcohol are the main factors leading to liver damage. Synergy between hepatitis B virus (HBV) and alcohol in promoting liver cell damage and disease progression has been reported. However, the interaction of HBV and ethanol in hepatic steatosis development has not been fully elucidated.

MethodsEight-week-old male C57BL/6 mice were treated with or without HBV, ethanol, or the combination of HBV and ethanol (HBV+EtOH), followed by a three-week high-fat diet (HFD) regimen. Liver histology, serum biomarkers, and liver triglyceride levels were analysed. Furthermore, a meta-analysis of the effects of alcohol and HBV on hepatic steatosis in populations was performed.

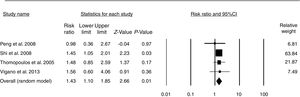

ResultsHepatic steatosis was significantly more severe in the HBV+EtOH group than in the other groups. The serum alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase and liver triglyceride levels in the HBV+EtOH group were also significantly higher than those in the other groups. The HBeAg and HBsAg levels in the HBV+EtOH group were significantly higher than those in the pair-fed HBV-infected mice. In addition, the meta-analysis showed that alcohol consumption increased the risk of hepatic steatosis by 43% in HBV-infected patients (pooled risk ratio (RR)=1.43, P<0.01).

ConclusionsAlcohol and HBV synergistically promote high-fat diet-induced hepatic steatosis in mice. In addition, alcohol consumption increases the risk of hepatic steatosis in HBV-infected patients.

Hepatitis B is the leading cause of chronic liver disease worldwide. Approximately 30% of the world's population is infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV). Every year, as many as 350 million people are infected with HBV, and more than 780 thousand people die from HBV-related diseases [1]. Steatosis is a common histopathological feature of chronic hepatitis B patients [2–4] and is observed in approximately 30% of cases [5,6].

Both ethanol and HBV target the liver, possibly resulting in hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [7,8]. Animal studies have shown that HBV-infected SCID mice fed a chronic alcohol diet have a 7-fold increase in serum HBV DNA levels and HBsAg levels [9]. In addition, there was a 2- to 4-fold higher levels of HBV markers in the serum of chronic alcoholics than in the general population [10–12]. These findings suggest synergy between HBV and alcohol in promoting liver cell damage and disease progression [13,14]. However, the interaction of HBV and ethanol in hepatic steatosis has not been fully elucidated.

Here, we speculate that alcohol and HBV may interact to cause hepatic steatosis. In this article, we studied the synergy between alcohol and HBV infection in promoting hepatic steatosis induced by a high-fat diet in mice. In addition, we conducted a meta-analysis of studies on alcohol consumption and the risk of hepatic steatosis in HBV-infected patients.

2Materials and methods2.1Mice and treatment schedulesAll animal care and experiments were carried out in strict accordance with the Animal Care and Use Guide and were approved by the ethics committee of Fudan University. C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Shanghai Model Organisms Center. Eight- to nine-week-old age-matched male mice were used in this study. All animals were housed under temperature-controlled and light-cycled conditions.

After one week on the basal diet, mice were randomised into 4 groups: group 1—three-week pair-fed+three-week HFD (pair-fed); group 2—HBV+three-week pair-fed+three-week HFD (HBV+pair-fed); group 3—three-week EtOH+three-week HFD (EtOH); and group 4—HBV+three-week EtOH+three-week HFD (HBV+EtOH). Each group contained 7–9 mice. Group 2 and group 4 were infected with HBV. Group 3 and group 4 were fed a Lieber-De Carli liquid ethanol diet (catalogue no. TP 4030B; TROPHIC Animal Feed High-tech Co., Ltd., Nantong, China) for 3 weeks. Group 1 and group 2 were fed an isocaloric control diet (catalogue no. TP 4030C; TROPHIC) for 3 weeks. In brief, mice were acclimated to the isocaloric diet for 3 days before the introduction of ethanol in the ethanol-fed groups (33% ethanol:67% isocaloric diet on days 4–6; 66%:33% on days 7–9; and 90%:10% starting on day 10 and continuing until day 21). Then, all mice were fed a 60% high-fat diet (HFD, catalogue no. D12492; Research Diets, Inc.) for three weeks.

2.2AAV/HBV infectionAAV/HBV virus was purchased from the Institute of Five Plus Molecular Medicine. Mice were injected with 1×1011 viral genome equivalents (vg) of recombinant virus through the tail vein within 6–8s [15].

2.3Serum biochemical analysisAfter 3 weeks of ethanol diet (EtOH) feeding and 3 weeks of high-fat diet (HFD) feeding, serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were measured using a kit from DREW Scientific (NJBI, China) following the manufacturer's instructions.

2.4ELISAOrbital blood was used to detect HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) and HBV e antigen (HBeAg). The levels of HBsAg and HBeAg in serum were measured by an ELISA kit (Shanghai Kehua Bioengineering Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer's instructions. The lower limit of detection for HBsAg and HBeAg was 0.5ng/ml. Serum dilutions of 1.5- to 90-fold were used to obtain values in the linear range of the standard curve.

2.5Search strategy and study selectionWe systematically searched the EMBASE and Medline databases to identify relevant articles published until August 2018. Our core search consisted of terms related to ‘steatosis’ and ‘fatty liver’ combined with ‘HBV’ to identify eligible studies. No language limits were set. Exclusion criteria were studies with indirect assessment of hepatic steatosis without liver biopsy; studies lacking sufficient information to calculate risk estimates with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs); and studies on patients with no evidence of active viral replication. In addition, all references listed in the retrieved articles and the reference lists of published meta-analyses [16] were scanned to further identify possible relevant publications. The following information was extracted from each of the eligible publications: steatosis prevalence, alcohol consumption, first author's name, publication year, study location, population ethnicity, age, sample size, sex and covariates adjusted for multivariable analysis.

2.6Statistical analysisThe results are shown as the means±SEMs. Statistical analysis was carried out by Student's t test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

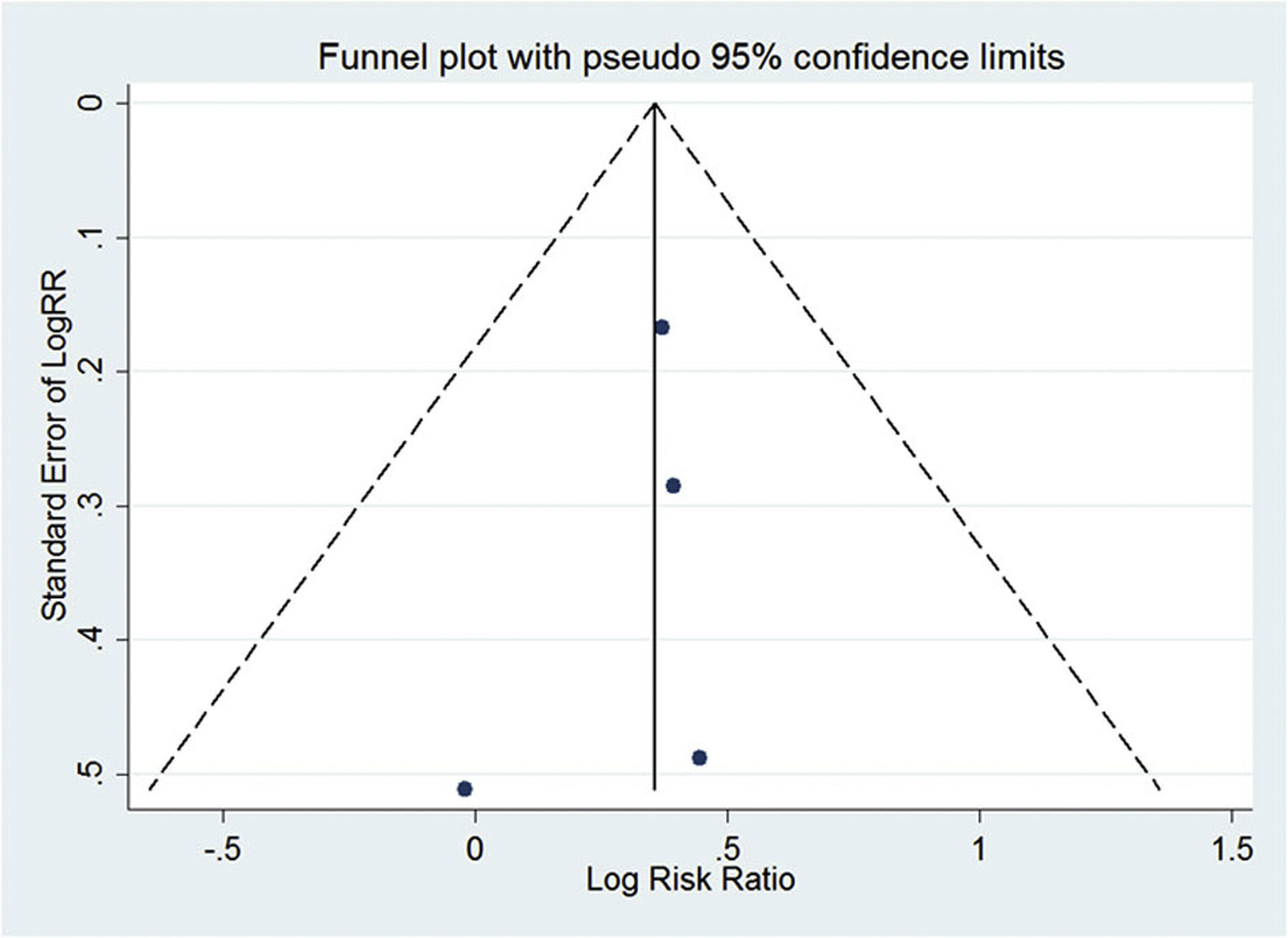

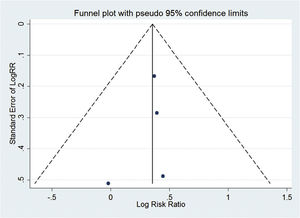

A random effects model [17] was used in the meta-analysis. The P value of the risk ratio (RR) was determined by a Z-test. Stata 12.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX) and Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software 2.0 (Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ) were used in statistical analyses. Evidence of publication bias was evaluated through visual inspection of funnel plots using Egger's regression test [18].

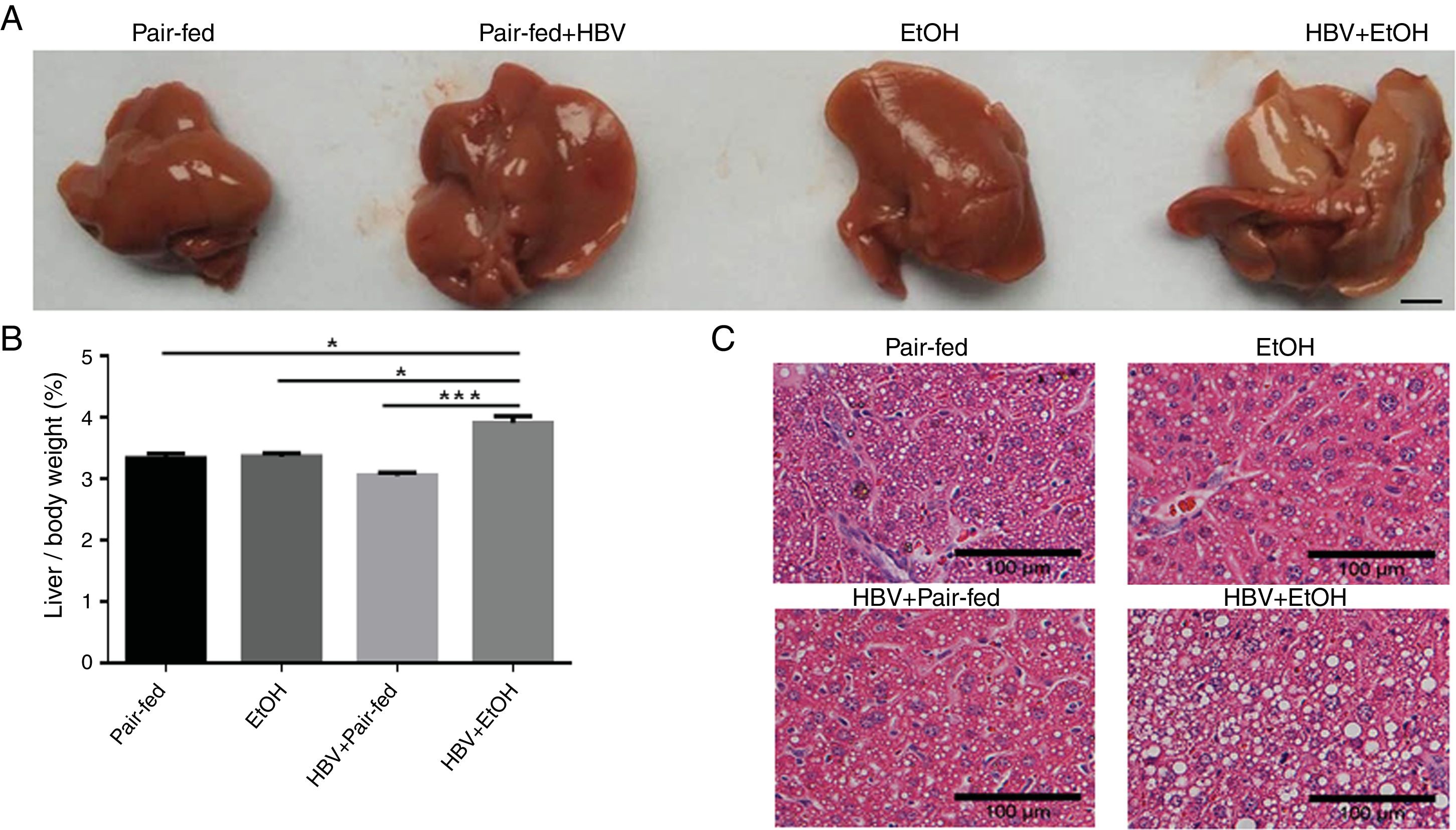

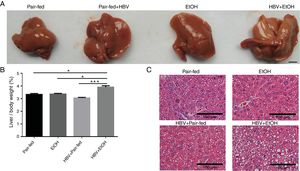

3Results3.1Ethanol and HBV synergistically potentiate hepatic steatosis in mice induced by a high-fat dietMacroscopically, the surface of the livers showed severe signs of steatosis in the HBV+EtOH group (Fig. 1A). The liver/body weight ratio in the HBV+EtOH group was significantly higher than that in the other groups (Fig. 1B). Microscopically, examination of liver pathology using haematoxylin-eosin staining showed more severe steatosis in hepatocytes in the HBV+EtOH group than in hepatocytes in the other groups (Fig. 1C). These results indicate that chronic ethanol feeding and HBV infection synergistically potentiate hepatic steatosis in mice fed a high-fat diet.

Effects of chronic ethanol feeding and HBV infection on hepatic steatosis in mice fed a high-fat diet. (A) Representative macroscopic view of a liver from each group. Scale bars: 10mm. (B) Liver/body weight ratio of each group. (C) Representative H&E staining of liver sections harvested from sacrificed mice. Scale bars: 100μm (n=9, 7, 5, and 5 in the pair-fed, HBV+pair-fed, EtOH, and EtOH+HBV groups, respectively; mean±SEM; *P<0.05, ***P<0.001).

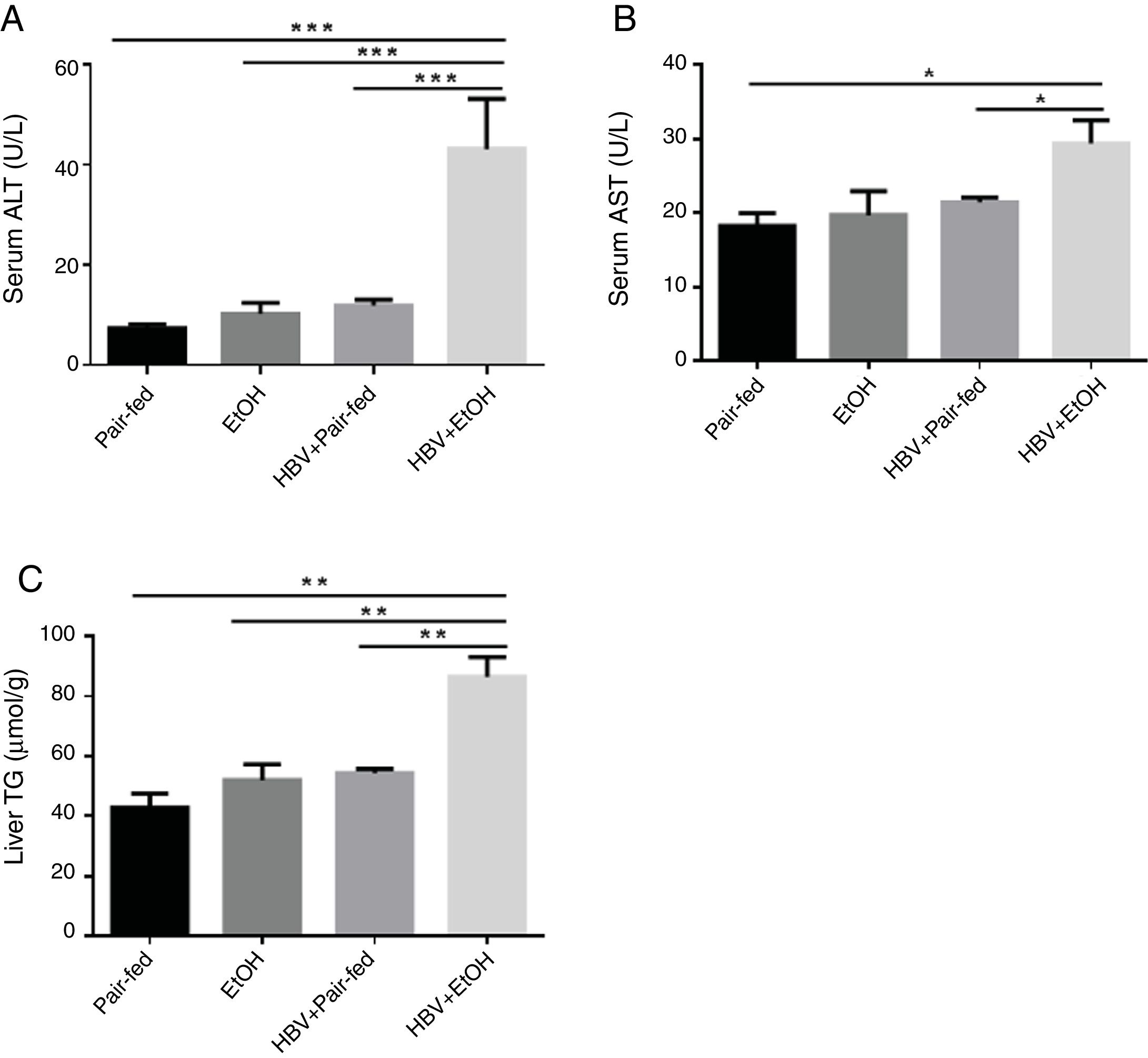

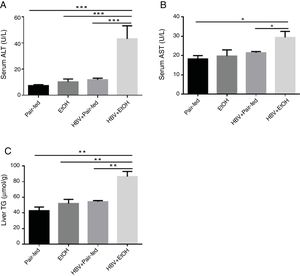

The effects of ethanol and HBV on the serum levels of AST, ALT and liver triglyceride (TG) in the model mice are shown in Fig. 2. The levels of AST, ALT and TG (Fig. 2A–C) were significantly increased in the HBV+EtOH group compared with those in the other groups.

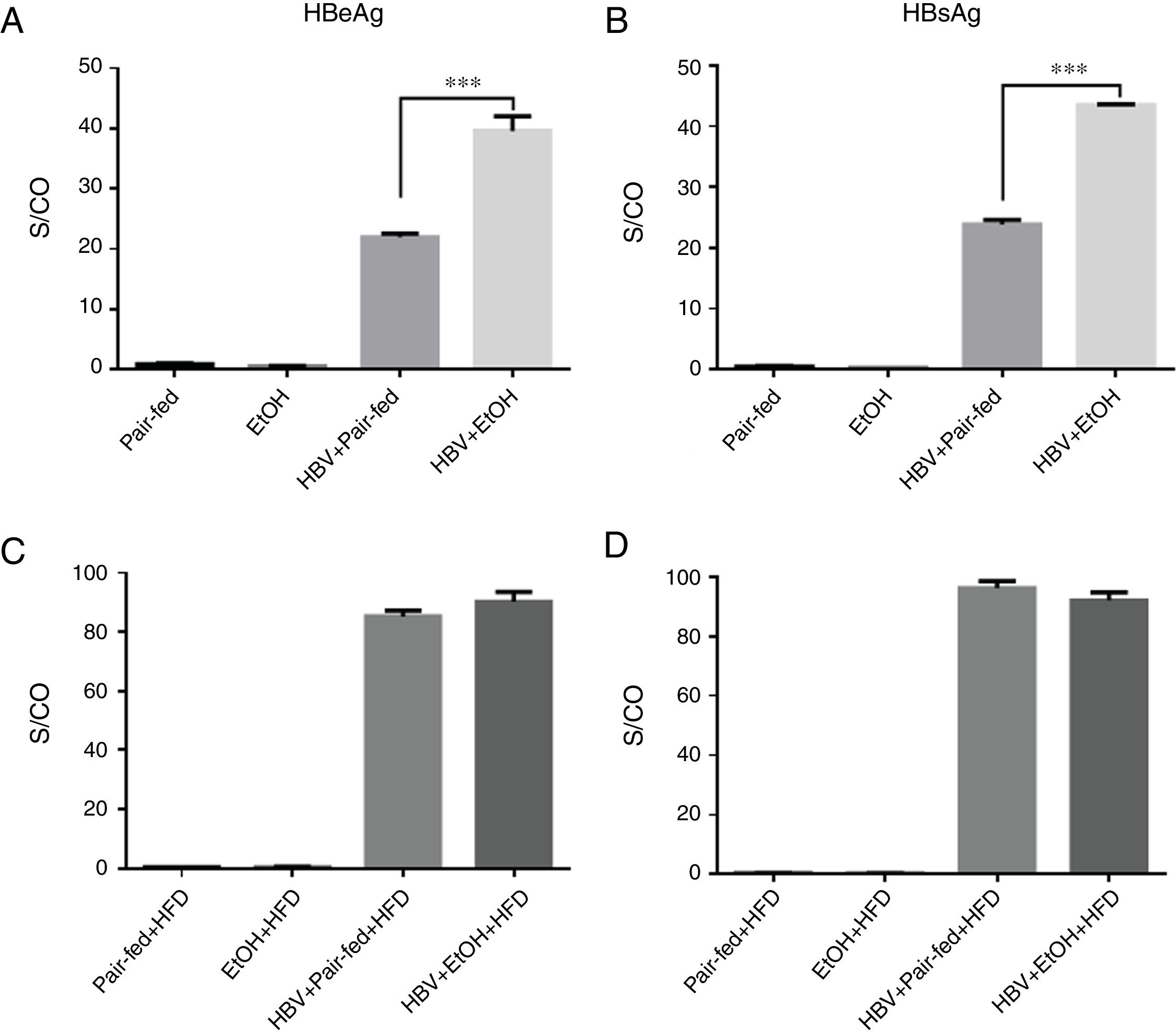

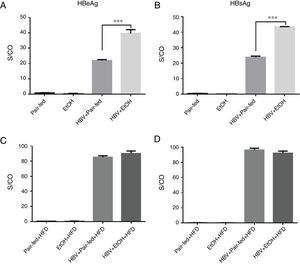

3.3Ethanol intake potentiates HBV replication in miceWe used tail vein injection of a plasmid containing a 1.3-fold HBV genome equivalent to achieve HBV persistence in mouse hepatocytes [19]. The results showed that HBeAg and HBsAg were detectable in the serum, indicating that HBV successfully replicated in mice (Fig. 3). Furthermore, our results showed a significant increase in HBV replication in the HBV+EtOH group compared with that in the other groups (Fig. 3A, B). Interestingly, there was no significant difference between these groups after ethanol retreatment during the following 3 weeks (Fig. 3C, D). These results indicate that ethanol intake potentiates HBV replication in C57BL/6 mice.

Serum HBeAg and HBsAg levels. (A and B) Serum HBeAg and HBsAg levels before high-fat diet feeding. (C and D) Serum HBeAg and HBsAg levels after 3 weeks of high-fat diet feeding. The levels of HBeAg and HBsAg are shown as the signal-to-control ratio (S/CO) (n=9, 7, 5, and 5 in the pair-fed, HBV+pair-fed, EtOH, and EtOH+HBV groups, respectively; mean±SEM; ***P<0.001).

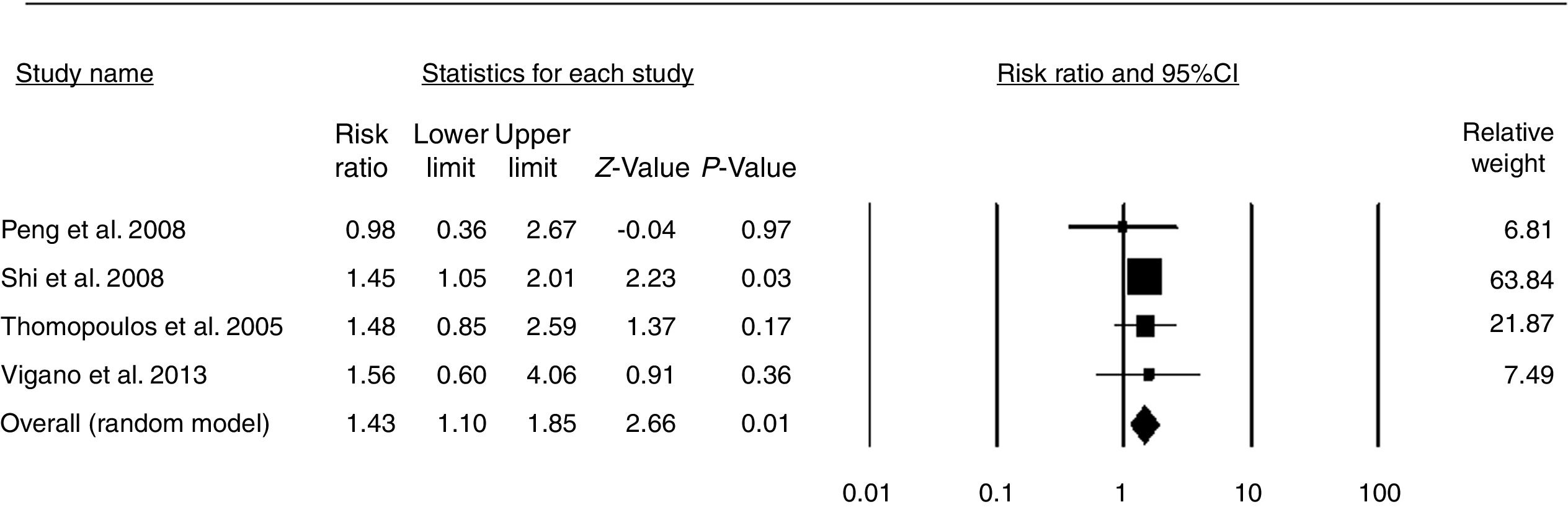

Then, we extracted clinical data about the effects of alcohol and HBV on hepatic steatosis. A total of 14 studies were selected [2–4,6,20–29], of which 10 were excluded. The reason for exclusion was a lack of information on alcohol intake. Based on these data, a comprehensive meta-analysis included 4 available studies [3,20,23,24] (before August 2018), and data from these studies were used to assess the relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk of hepatic steatosis in HBV-infected patients. In this study, the effect size was the risk ratio. The pooled risk ratio (RR) indicated that moderate alcohol consumption increases the risk of hepatic steatosis in HBV-infected patients (pooled RR=1.43, P<0.01) (Fig. 4). No evidence for publication bias was indicated by Egger's regression test (P=0.526) (Fig. S1).

4DiscussionSteatosis is a common histopathological feature of chronic hepatitis B patients [2–4]. In addition, synergy between hepatitis B virus (HBV) and alcohol in promoting liver cell damage and disease progression has been reported. Thus, it was reasonable to suspect that alcohol and HBV may interact with each other to affect hepatic steatosis. In the present study, we identified the synergy of ethanol and HBV in promoting hepatic steatosis.

The most striking finding was that feeding alcohol to HBV-infected mice caused much more severe steatosis than pair-feeding (Fig. 1). These results, along with the enhanced intrahepatic TG levels and serum ALT and AST levels, suggest conspicuous synergism of alcohol and HBV. Synergy between HBV and alcohol in promoting liver cell damage and disease progression has also been reported [16,17]. Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that alcohol and HBV synergistically promote hepatic steatosis in mice.

In addition, we were the first to find that alcohol can promote HBV replication in an HBV-immunocompetent mouse model. After feeding HBV-infected mice alcohol for 3 weeks, the HBeAg and HBsAg levels were significantly higher than those in pair-fed HBV-infected mice. This result was consistent with previous findings in immunodeficient transgenic mice [30] and cell models [31]. These observations suggest that ethanol consumption could stimulate HBV replication independent of the host immune state.

Notably, the meta-analysis in this study revealed the effect of alcohol consumption on the risk of hepatic steatosis in HBV-infected patients. Four studies, comprising 2536 patients, that evaluated the effect of alcohol consumption on the risk of hepatic steatosis were included [3,20,23,24]. The pooled data showed an increased risk in alcohol-consuming populations (Fig. 4). A risk ratio of 1.0 means that the risk of hepatic steatosis is the same in both groups; a risk ratio of less than 1.0 means that the risk is lower in the moderate alcohol consumption group, and a risk ratio of greater than 1.0 means that the risk is lower in the control group [32]. Thus, the pooled RR (1.43) indicated that moderate alcohol consumption increased the risk of hepatic steatosis by 43% compared with that of HBV-infected patients who did not drink. These results suggest that alcohol consumption seems to have a pathological role in HBV-infected patients. Due to the limited work performed in this field, more relevant clinical studies are needed to verify this finding.

The limitation of our study is that the mechanisms underlying the interaction between HBV and ethanol on hepatic steatosis were not investigated. Further studies are warranted to determine the mechanisms of HBV and ethanol in steatosis.

5ConclusionIn summary, to our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate the synergistic effect of HBV and ethanol on promoting hepatic steatosis. These data provide a rationale for alcohol abstinence in HBV-infected patients.AbbreviationsHBV

hepatitis B virus

HFDhigh-fat diet

ALTalanine aminotransferase

ASTaspartate aminotransferase

ALDalcoholic liver disease

NAFLDnon-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

This work is supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81872245 and 81803601) and grants from the Shanghai Sailing Program (17YF1416700).