Editado por: Marco Arrese - Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, Santiago, Chile

Última actualización: Noviembre 2023

Más datosAlcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) represents one of the deadliest yet preventable consequences of excessive alcohol use. It represents 5.1 % of the global burden of disease, mainly involving the productive-age population (15-44 years) and leading to an increased mortality risk from traffic road injuries, suicide, violence, cardiovascular disease, neoplasms, and liver disease, among others, accounting for 5.3 % of global deaths. Daily alcohol consumption, binge drinking (BD), and heavy episodic drinking (HED) are the patterns associated with a higher risk of developing ALD. The escalating global burden of ALD, even exceeding what was predicted, is the result of a complex interaction between the lack of public policies that regulate alcohol consumption, low awareness of the scope of the disease, late referral to specialists, underuse of available medications, insufficient funds allocated to ALD research, and non-predictable events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, where increases of up to 477 % in online alcohol sales were registered in the United States. Early diagnosis, referral, and treatment are pivotal to achieving the therapeutic goal in patients with alcohol use disorder (AUD) and ALD, where complete alcohol abstinence and prevention of alcohol relapse are expected to enhance overall survival. This can be achieved through a combination of cognitive behavioral, motivational enhancement and pharmacological therapy. Furthermore, the appropriate use of available pharmacological therapy and implementation of public policies that comprehensively address this disease will make a real difference.

Excessive alcohol use is one of the leading preventable risk factors for physical and social harm globally. It causes 5.3 % of global deaths and 5.1 % of the global burden of disease and injury, and it remains the leading cause of cirrhosis [1,2]. Most of the alcohol-related disease burden impacts individuals aged between 15–44, thus affecting mostly young people in their most productive years of life [2,3]. Alcohol-related harm can affect individuals in the short and long term, including traffic road injuries, suicide, violence, cardiovascular disease, neoplasms, and liver disease, among others [4]. For example, alcohol misuse increases cardiovascular mortality by 3.2-fold and cancer mortality by 5.1-fold, among others [4–6]. Alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) represents one of the most deadly consequences of alcohol use [7]. In addition, alcohol can interact with insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes mellitus, overweight, and obesity, among other metabolic risk factors, thereby increasing the development and progression of chronic liver disease in susceptible individuals [8]. Due to this interaction, a multi-society including the Latin American Association for the Study of the Liver (ALEH), the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), and the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) proposed a new definition of steatotic liver disease, including specific diagnostic criteria for ALD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), and the intersection between both conditions (MetALD) [9]. The COVID-19 pandemic has also had a negative impact on alcohol consumption patterns worldwide, which is expected to increase ALD burden in the near future. Regions with a rising burden of alcohol-related cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) should consider policies to reduce alcohol misuse, such as enforcement of a minimum price for alcohol, increased alcohol taxation, and implementation of alcohol advertising bans [10].

2Global burden of alcohol-associated liver disease: A rising threatALD has a wide spectrum of liver injury patterns, ranging from isolated steatosis, which develops in 90–95 % of heavy drinkers, to more advanced forms, such as alcohol-associated steatohepatitis (ASH) (20–40 % of heavy drinkers) with or without fibrosis, cirrhosis (8-20 % of ASH) and ultimately portal hypertension, decompensation, and HCC. During the natural history of this condition, some patients will experience an episode of alcohol-associated hepatitis (AH), portending a worse prognosis with a 3-month mortality reaching 30–40 % [11,12]. ALD prevalence varies across different settings, with a recent systematic review showing a prevalence of 3.5 % (95 % CI, 2.0 %–6.0 %) among an unselected population, whereas in groups with alcohol use disorder (AUD) the prevalence of ALD and alcohol-associated cirrhosis reached 55.1 % (95 % CI, 17.8 %-87.4 %) and 12.9 % (95 % CI, 4.3 %-33.2 %), respectively [13]. Although most people who regularly consume heavy amounts of alcohol develop any degree of ALD, only a small proportion progress to cirrhosis or liver cancer. A combination of behavioral (amount of drinking, pattern, type), environmental (other comorbid conditions such as obesity, metabolic syndrome, viral hepatitis, smoking) and genetic (Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 PNPLA3 i140m variant genotype, 17B-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-13 HSD17B13, Transmembrane 6 superfamily 2 TM6F2) or epigenetic factors are likely to determine individual susceptibility to progression to advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis among heavy drinkers, but the mechanisms are largely unknown [14]. Alcohol consumption remains the leading cause of cirrhosis globally and is responsible for almost 60 % of cirrhosis burden in Europe, North America, and Latin America, while hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection remains the leading cause in Southeast Asia, Africa, and East Mediterranean regions [2]. In 2019, alcohol was responsible for 25 % and 19 % of estimated deaths from alcohol-associated cirrhosis and liver cancer, respectively, with its highest impact centered in Europe and the Americas (42 % and 35 % of deaths, respectively) [15]. Among patients without HCC, ALD remains the leading indication for liver transplantation (LT), followed by metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) (previously known as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis –NASH–), accounting for 38 % and 28 %, respectively [9,16]. The global incidence of AH has increased in recent years, especially in young people and women. There is a predicted increase of 77 % in the age-standardized incidence of decompensated alcohol-associated cirrhosis, from 9.9 cases per 100,000 patient-year in 2019 to 17.5 cases per 100,000 patient-years in 2040, if current trends are left unchecked and no new policies are applied worldwide [17]. Despite the enormous threat to global health, ALD remains underfunded and under-researched in relation to the high burden associated with it, and an additional €83 million would need to be allocated to ALD research to achieve a proportionate amount of research funding relative to its disease burden.

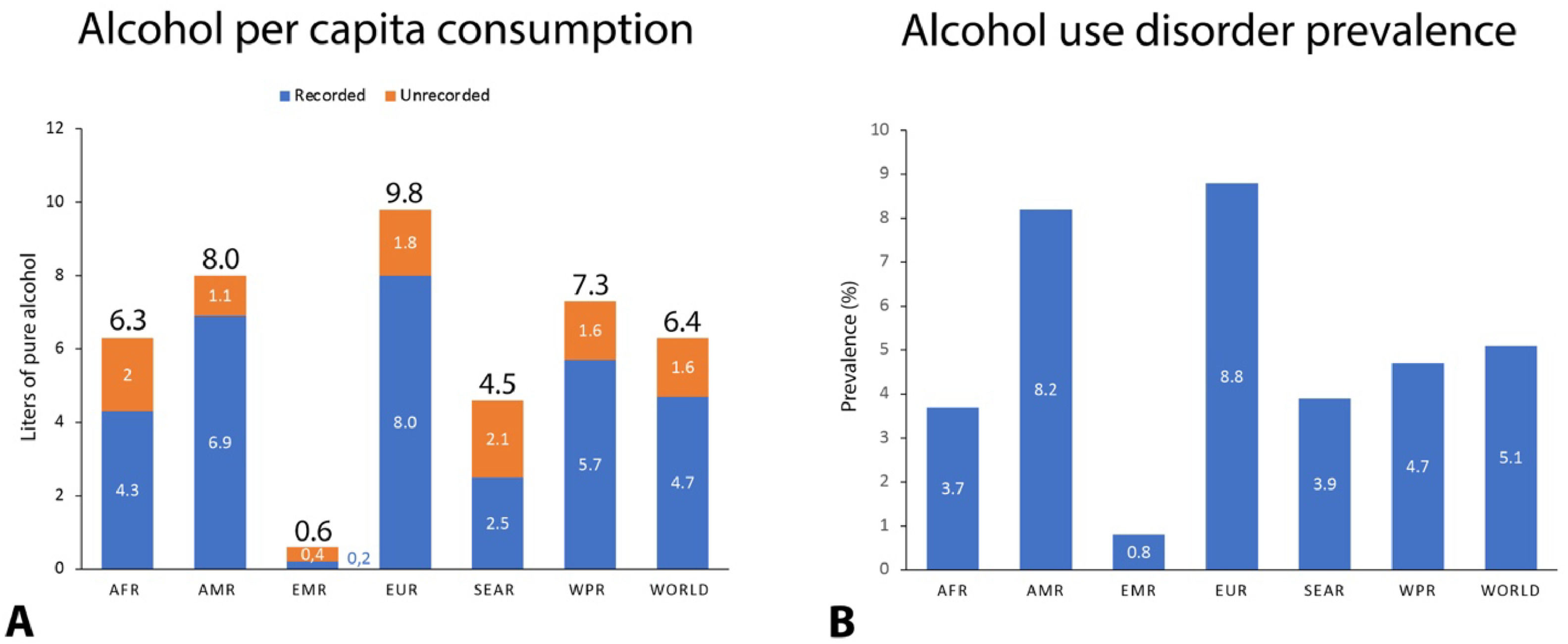

3Increasing trends in alcohol consumption worldwide: Before and after COVID-19 pandemicHazardous alcohol intake is responsible for 3 million deaths every year worldwide, representing 5.3 % of all deaths (13.5 % of all deaths in people aged 20-39 years) and 5.1 % of the global burden of disease and injury as measured in disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), which is defined as the sum of the years of life lost due to premature mortality and the years lived with a disability due to prevalent cases of the disease or health condition in a population, with an estimate 139 million DALYs attributable to alcohol intake [1]. Levels of alcohol consumption can be measured using several indicators. One is the prevalence of current drinkers or abstainers in a country or region. In 2016, 2.3 billion people (43 % of the global population) were current alcohol drinkers (individuals who have consumed alcoholic beverages in the previous 12-month period), with 40 % of those being heavy drinkers. The global AUD prevalence was 5.1 %, being more prevalent in men and among the European Region and the Americas. Around 35 % of AUD patients will develop ALD in the long term [1,5]. Total alcohol per capita consumption (APC) is another commonly used indicator of alcohol consumption, and it is defined as the total (recorded plus estimated unrecorded) alcohol per capita (i.e., persons aged 15 years or older) consumption within a calendar year in liters of pure alcohol. In 2016, the total APC was 6.4 liters (compared to 5.0 liters in 2000), which translates into 13.9 grams of pure alcohol per day, being highest in Europe (9.8 liters, 21.3 grams per day) and the Region of the Americas (8.0 liters, 17.4 grams per day) while lowest in the Eastern Mediterranean region (0.6 liters, 1.2 grams per day), (Fig. 1). Considering those individuals with a regular alcohol intake, total APC increases to 15.1 liters (32.8 grams per day) [1]. These marked geographic differences are the result of complex interactions between socio-demographic factors, economic development, religion and cultural norms, and preferred alcoholic beverage types. Also, not only the volume but the frequency of this alcohol consumption has a direct impact on liver health. Daily drinking (defined as consuming alcohol seven days per week or almost every day) conditions a constant exposure to high circulating levels of acetaldehyde, with its consequent activation of the enzyme cytochrome p450 2E1(CYP2E1) and formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), that are toxic for the liver. Therefore, at least two days alcohol-free per week are needed to allow the liver to recover. Daily alcohol intake increases the risk of developing liver cirrhosis (LC) compared to non-daily drinking in both sexes (RR 1.71 for men and 1.56 for women) and increases the risk of all-cause mortality [18]. Another commonly used definition is heavy alcohol consumption (HAC), which is defined as the consumption of > 40 g of pure alcohol per day over a sustained period or the ingestion of > 7 drinks per week for women or > 14 drinks per week for men. Besides HAC, binge drinking (BD) and heavy episodic drinking (HED) are associated with an increased risk of developing ALD. BD, as defined by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), is a pattern of alcohol consumption that brings blood alcohol concentration to ≥0.08 % (or 0.08 grams per deciliter or more), which typically occurs following the intake of >5 drinks by men and >4 drinks by women over a period of approximately 2 hours at least once a month [19]. HED, on the other hand, is defined as the consumption of 60 grams or more of pure alcohol on at least one occasion at least once per month. In 2018, 16.6 % of United States (US) adults aged > 18 years (38.5 million adults) reported BD during the past 30 days, being more common among men (22.5 % vs. 12.6 %) and those aged 25–34 years (26 %). Binge drinking is on the rise among older adults, with 11.4 % of adults aged > 65 years reporting BD in the prior month [20]. In 2016, Across all World Health Organization (WHO) regions, HED was most prevalent among people aged 20-24 years, and its prevalence in men and women in 2017 was 29 % and 11 % respectively [1].

Global and regional level of alcohol use and alcohol use disorder prevalence in 2016. Data was obtained from the Global Information System on Alcohol and Health (GISAH) of the World Health Organization (WHO), and the regions were categorized according to the WHO regions. AFR, African Region; AMR, Region of the Americas; SEAR, Southeast Asian Region; EUR, European Region; EMR, Eastern Mediterranean Region; WPR, Western Pacific Region.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a dramatic impact on both the physical and mental health of people, and during the pandemic, there was a spike in alcohol use in the general population, with a 477 % increase in online alcohol sales in the United States and a 38 % relative increase in monthly alcohol sales in Canada. Of individuals with pre-existing AUD, 24 % reported an increase in their alcohol use, with an average of 48.8 units of alcohol per week after lockdown [21–23]. Such findings were also seen in the United Kingdom (UK), Poland, and Belgium (14 % increased their intake during quarantine) and most likely worldwide. Presumed factors that increased alcohol use during the COVID-19 pandemic include adverse economic effects, disruptions in work and education, psychosocial stressors associated with limitations on social gatherings, social isolation, and shifts in alcohol consumption from bars/restaurants to at-home use. In the US, there was a 107 % and 210 % increase in new listings and transplants, respectively, for cases of AH between March 2020 and February 2021 compared with March 2018 through February 2020, accounting for 40 % of all LT in North America, more than MASH and HCV combined [24]. A sharp increase in all-cause mortality due to ALD was seen during the pandemic, with a quarterly rate increase of 11.2 % compared to 1.1 % in the pre-COVID-19 era [25]. Also, an accelerated annual percentage change (APC) of all-cause age-standardized mortality rate (ASMR) in ALD was found, with a change of 3.5 % (95 % IC 3.0–3.9) for 2010-2019 to 17.6 % (95 % IC 12.2–23.2) for 2019–2021, compared to all-cause ASMR trend for viral hepatitis, which was either stable or declining. As a result, the observed ASMRs of 15.67 for ALD in 2020 and 17.42 in 2021 were much higher than the predicted values (13.04 and 13.41, respectively). Liver-related ASMRs followed similar trends [26]. Two recent multicentric cohort studies also showed that ALD was an independent risk factor for death due to COVID-19 [27,28]. It is known that patients with cirrhosis have elevated levels of endotoxins, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and increased gut permeability, potentially predisposing them to a higher risk of death in the setting of SARS-CoV2 infection, while COVID-19 could also induce liver injury [29]. This increase in alcohol consumption could further increase the global burden of ALD in the coming years.

4Early diagnosis, referral, and treatment: A call to actionDetecting ALD at early stages is a key step to prevent its associated morbidity and mortality. Much more effort should be taken worldwide to identify patients with AUD and early-stage disease to prevent disease progression and development of liver-related and non-liver-related complications. AUD should be screened in all patients with standardized questionnaires such as the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), its simplified version AUDIT-C, CAGE (Cut down, Annoyed, Guilty, Eye opener), and diagnosed by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th edition (DSM-5) criteria. Current evidence reflects a lack of awareness/screening among physicians, and ALD is often identified in advanced stages with decompensated cirrhosis. In a recent multicenter retrospective cross-sectional study performed at 17 tertiary care units worldwide, it was found that only 3.8 % of patients evaluated with early-stage liver disease (defined as non-cirrhotic liver disease without previous liver-related complications) had ALD. In contrast, 29 % of patients evaluated for advanced disease (defined as decompensated cirrhosis) had ALD. Compared with patients with HCV-related liver disease, patients with ALD were more than 14-fold more likely to be diagnosed with advanced-stage disease (odds ratio OR 14.1 95 % IC 10.5-18.9) with an alarming advanced/early OR of 306 and 51.7 in Oceania and Europe, respectively [30].

Total alcohol abstinence and alcohol relapse prevention are the goals of therapy in patients with AUD and ALD, with the combination of cognitive-behavioral therapy, motivational enhancement therapy, 12-step programs (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous), and pharmacotherapy [31,32]. Currently, there are only three Food and Drug Administration (FDA) - approved medications for alcohol use disorder (MAUD), disulfiram, acamprosate, and naltrexone, which have been associated with improved rates of abstinence, reduced binge drinking, and decreased rate of AUD-related hospitalizations [33]. Other non-FDA-approved medications, such as gabapentin, baclofen, and topiramate, have been used off-label with varying degrees of success [31]. In a retrospective study of a well-characterized cohort of patients with AUD (11.8 % of them having ALD), patients who were exposed to medical addiction therapy (40.5 % of the cohort) had reduced odds of developing ALD (adjusted odds ratio aOR, 0.37; 95 % CI, 0.31-0.43) in a dose-dependent fashion, with gabapentin having the lowest odds (aOR, 0.36; 95 % CI, 0.30-0.43). In addition, pharmacotherapy for AUD was associated with a lower incidence of hepatic decompensation (aOR, 0.35; 95 % CI, 0.23-0.53) even if treatment was initiated after the diagnosis of cirrhosis [34]. In a recent retrospective cohort study, pharmacotherapy for AUD improved survival in patients with alcohol-associated cirrhosis and AUD with a 20 % reduced hazard ratio of all-cause mortality (HR 0.80, 95 % CI 0.67-0.97) [35].

Naltrexone, acamprosate, gabapentin, topiramate, and baclofen are considered safe in patients with cirrhosis, although evidence is mostly derived from retrospective data. Baclofen is the only medication that has been compared versus placebo in a randomized controlled trial in patients with cirrhosis, at a dose of 10 mg PO TID, being associated with an OR of 6.3 (95 % CI, 2.4-16.1) of achieving and maintaining abstinence without hepatic-side effects, although few patients were allocated (42 patients in each treatment group, Child B 48 %, Child C 43 %) [36]. In a recent retrospective cohort study of adults with or without ALD who were prescribed naltrexone for AUD (47 patients with cirrhosis, Child B 37 %, Child C 21 %), it was demonstrated to be safe in patients with AUD and ALD, although more safety data are needed for those with decompensated cirrhosis [37]. Acamprosate, gabapentin and topiramate have no or minimal hepatic metabolism. Special considerations must be taken in patients with impaired renal function who are using AUD pharmacotherapy [33].

One of the most important challenges we face nowadays is that these medications are being underutilized by physicians, with multiple reasons being involved, such as lack of access, cost, discomfort when prescribing them, and concerns about safety and efficacy, reflecting a lack of exposure to AUD pharmacotherapy and participation in addiction clinics during training. Strikingly, among AUD and ALD patients, only 3 % and 1.4 % receive AUD pharmacotherapy [38].

5Towards a societal approach: combination of public health policies is neededIn 2010, member states of the World Health Organization (WHO) agreed to the Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol, thereby recognizing the issue as a key public health priority, with the goal of achieving a 10 % relative reduction of harmful alcohol use by 2025, although in some regions, such as Latin America, the implementation of these measures has been slow and deficient, with only 10 % having a written national plan [39]. Among several high-impact interventions policy-makers, taxation, restrictions on the availability of alcohol, and bans on alcohol advertising were identified as “best buys” for alcohol policy. Alcohol excise taxes are the most employed intervention, with 84 % of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries taxing all beverages (wine, beer, and spirits), although only 27 % of those periodically adjust taxes for inflation, contributing to rising alcohol affordability [40]. In a recent modelling study, the introduction of a minimum tax share of 25 % could avert 40,033 (95 % CI:38,054-46,097) deaths in the WHO European region [41]. Some regions have implemented a minimum unit pricing (MUP), which has been associated with reduced population-level alcohol sales by 3 %. A recent controlled interrupted time series study showed that the implementation of a MUP of £0.50 per unit of alcohol in Scotland since 2018 was associated with a 13.4 % reduction in deaths attributable to alcohol consumption [42]. Restricting the availability of alcohol is another useful policy intervention. Nevertheless, less than half (43 %) of all OECD countries regulate the hours alcohol can be sold, and a similar number apply no restrictions at all. Advertising restrictions represent a major challenge to policy-makers, with digital media replacing traditional media with its ubiquitous reach and continual creation of user-generated content [40].

In 2018, the WHO launched the SAFER initiative to support Member States in reducing the harmful use of alcohol. Thus, SAFER is focused on the most cost-effective priority interventions (“best buys”) using a set of WHO tools and resources to prevent and reduce alcohol-related harm: strengthen restrictions on alcohol availability; advance and enforce drunk driving countermeasures; facilitate access to screening, brief interventions, and treatment; enforce bans or comprehensive restrictions on alcohol advertising, sponsorship, and promotion; and raise prices on alcohol through excise taxes and pricing policies [43]. Recently, the WHO also released the Global alcohol action plan 2022-2030 to effectively implement the global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol as a public health priority (Table 1).

The World Health Organization (WHO) Global alcohol action plan 2022-2030 and the proposed global targets.

| Action area | Global targets |

|---|---|

| 1. Implementation of high-impact strategies and interventions | 1.1: By 2030, at least a 20 % relative reduction (in comparison with 2010) in the harmful use of alcohol.1.2: By 2030, 70 % of countries have introduced, enacted, or maintained the implementation of high-impact policy options and interventions. |

| 2. Advocacy, awareness and commitment | 2.1: By 2030, 75 % of countries have developed and enacted national written alcohol policies.2.2: By 2030, 50 % of countries have produced periodic national reports on alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harm. |

| 3. Partnership, dialogue and coordination | 3.1: By 2030, 50 % of countries have an established national multisectoral coordination mechanism for the implementation and strengthening of national multisectoral alcohol policy responses.3.2: By 2030, 50 % of countries are engaged in the work of the global and regional networks of WHO national counterparts for international dialogue and coordination on reducing the harmful use of alcohol. |

| 4. Technical support and capacity-building | 4.1: By 2030, 50 % of countries have a strengthened capacity for the implementation of effective strategies and interventions to reduce the harmful use of alcohol at national level.4.2: By 2030, 50 % of countries have a strengthened capacity in health services to provide prevention and treatment interventions for health conditions due to alcohol use in line with the principles of universal health coverage. |

| 5. Knowledge production and information systems | 5.1: By 2030, 75 % of countries have national data generated and regularly reported on alcohol consumption, alcohol-related harm and implementation of alcohol control measures.5.2: By 2030, 50 % of countries have national data generated and regularly reported on monitoring progress towards the attainment of universal health coverage for AUDs and major health conditions due to alcohol use. |

| 6. Resource mobilization | 6.1: At least 50 % of countries have dedicated resources for reducing the harmful use of alcohol by implementing alcohol policies and by increasing coverage and quality of prevention and treatment interventions for disorders due to alcohol use and associated health conditions. |

ALD remains among the foremost preventable causes of mortality attributable to excessive alcohol consumption within the economically active population, with an increasing trend in prevalence and great economic burden. Despite this, it continues to be understudied and underfunded. The difference between alcohol consumption patterns around the world is the result of a complex interaction between behavioral and genetic or epigenetic factors, as well as the socio-demographic, economic, and cultural environment.

The exponential increase in global alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic will generate a significant rise in the burden of ALD in the near future, paralleling the observed increase in the demand for liver transplantation due to AH. Also, a sharp increase in all-cause mortality due to ALD was seen during the pandemic, with a quarterly rate increase of 11.2 % compared to 1.1 % in the pre-COVID-19 era. In susceptible individuals, the coexistence of alcohol-associated liver disease with cardiometabolic factors increases the development and progression of chronic liver disease.

Naltrexone, acamprosate, gabapentin, topiramate, and baclofen are generally considered safe in patients with cirrhosis, although most evidence is derived from retrospective data. The referral of these patients from the first to the second level is suboptimal due to the tendency to attend to complications and not focus on prevention. Instructions should be given on timely initiation of medications once the onset of ALD is detected, and not wait for advanced stages. Policies like taxation, restrictions on alcohol availability, bans on alcohol advertising and implementation of minimum unit pricing (MUP) have been identified as effective interventions to reduce ALD burden.

Author contributionsAll authors contributed to the design, implementation, and analysis of the research, as well as to the writing of the manuscript.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.