Introduction and aim. The carcinogenesis of tubular and papillary cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) differ. The available epidemiologic studies about risk factors for CCA do not differentiate between the tubular and papillary type. The current study investigated the relationship between the number of repeated use of Praziquantel (PZQ) treatments and each type of CCA.

Material and methods. This was a hospital-based, matched, case-control study of patients admitted to Srinagarind Hospital, Khon Kaen University. The patients were 210 pathologically-confirmed cases of CCA, while the controls were 840 subjects diagnosed with other diseases. The 4 controls were individually matched with each case by sex, age, and date of admission. The cases were classified according to location (intrahepatic vs. extrahepatic) and cell type (papillary vs. tubular). Multivariable conditional logistic regression was used for the analysis.

Results. After adjusting for confounders, there were statistically significant associations between intrahepatic and papillary CCA and repeated use of PZQ treatment. The respective odds of developing intrahepatic CCA for those who used PZQ once, twice, or more was 1.54 (95%CI:0.92-2.55 ), 2.28 (95%CI:0.91-5.73), and 4.21 (95%CI:1.61-11.05). The respective odds of developing papillary CCA for those who used PZQ once, twice, or more was 1.45 (95%CI:0.80-2.63), 2.96 (95%CI:1.06-8.24), and 3.24 (95%CI:1.09-9.66). There was no association between number of uses of PZQ treatment and developing extrahepatic or tubular CCA.

Conclusion. The current study found an association between papillary and intrahepatic CCA and repeated use of PZQ treatment. We suggest further study on the risk factors for papillary and tubular CCA should be performed separately.

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) remains an important public health problem in many parts of the world. Although most patients with CCA do not have any apparent risk factors, several risk factors have been confirmed including hepatolithiasis, toxins, biliary tract disorder, and parasitic infection.1,2 The liver flukes associated with CCA include Opisthorchis viverrini3 and Clonorchis sinensis.4,5

Opisthorchiasis-induced CCA has been studied extensively. Numerous government policies have been implemented to eradicate O. viverrini infection; such as promoting consumption of cooked fish and providing anti-helminthic drugs, but the problem persists.6

The standard treatment for O. viverrini is Praziquantel (PZQ), which is effective against almost all flat worm parasites. Although the safety of a single treatment with PZQ has been demonstrated,7,8 there is concern regarding the potential harm of repeated treatments with PQZ.9 Our team reported that repeated PQZ treatment is associated with an increased risk of CCA.10 Since the use of PZQ is associated with eating raw fish,11 we concluded that repeated PZQ treatment may be a surrogate marker for eating raw fish and O. viverrini infection rather its than causing CCA itself.10

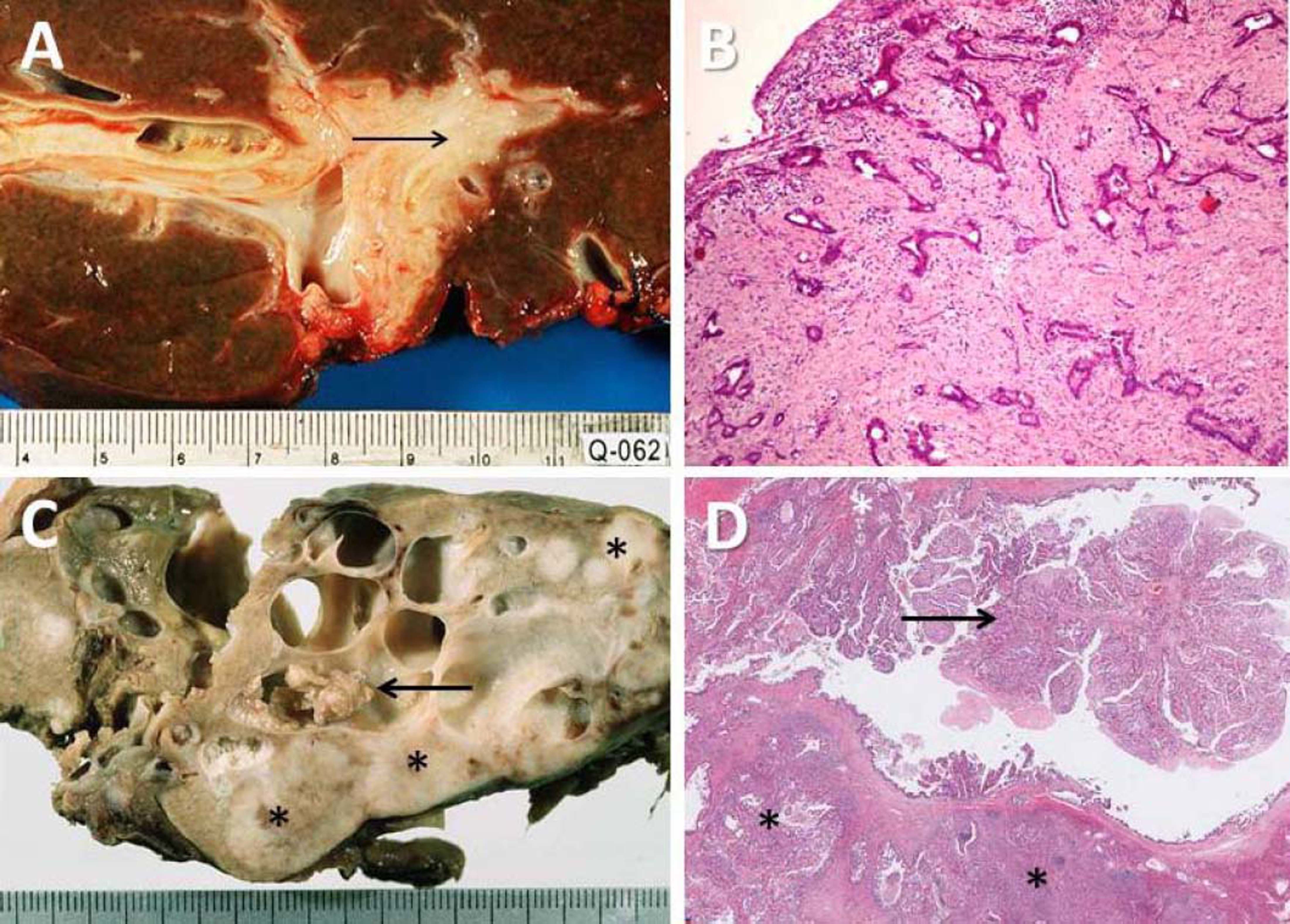

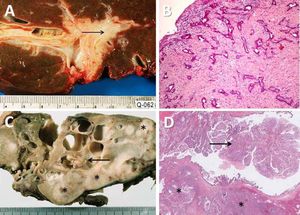

Cholangiocarcinoma is a heterogeneous group of bile duct cancers currently classified as intrahepatic and extra-hepatic CCA), the second order bile ducts (intrahepatic segment ducts) representing the separation point. Tumours proximal to the right or left hepatic duct are considered intrahepatic (ICC) (Figure 1), while extrahepatic CCA (ECC) is divided into perihilar (proximal) and distal, at the cystic duct junction. ICC has been classified according to growth patterns as:

- •

The mass-forming type.

- •

The periductal infiltrating type (PI).

- •

The intraductal growing type (IG) (Figure 1).

Pathological features of two major types of large duct intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. A,B. Tubular adenocarcinoma. A. Periductal infiltrating type. The carcinoma spreads along the intrahepatic bile duct (arrow). B. The tubular-forming carcinoma glands infiltrate the bile wall. Note how the desmoplastic reaction compresses the glands. The surface epithelia at the luminal surface are denuded. C,D. Papillary carcinoma (invasive IPNB). C. The intraductal polypoid tumour presents in the dilated intrahepatic biliary tree (arrow). Multiple white nodules of invasive carcinoma locate in the liver parenchyma (asterisk). D. Neoplastic biliary epithelia show papillary growth in the dilated lumen (arrow). The carcinoma invading the bile duct wall (white asterisk) and infiltration in the nearby liver tissue (asterisk).

The latter two can turn into a focal liver mass if there is invasion of the liver parenchyma. The PI and IG arising from the intrahepatic large bile duct are comparable to flat or nodular-infiltrating and polypoid lesions, respectively, of the extrahepatic large bile duct. Unique pre-invasive lesions appear to precede the individual gross types of CCA.12 Biliary intraepithelial neoplasia -a flat dysplastic lesion- precedes periductal-, flat-, and nodular-infiltrating CCAs by way of a metaplasia-dysplasia sequence, whereas intraductal papillary neoplasms of the bile duct (IPNB) precede intraductal-growth and papillary types of CCAs by way of an adenoma-carcinoma sequence.13 Owing to the described differences in pathogenesis between these two types of bile duct tumor, we hypothesized that the risk factors for the two would also be different; however, the available epidemiological studies regarding the risk factors of CCA do not differentiate between the tubular and papillary type.

To achieve a better understanding of the association between the repeated use of PZQ treatment and the types of CCA, we investigated the relationship between the number of times PZQ treatment was used with respect to each type CCA.

Material and MethodsThis was a hospital-based, matched, case-control study of patients admitted to Srinagarind Hospital, Khon Kaen University. The data used for the analysis were the same as those compiled for our previous study, which included 210 pathologically-confirmed cases of CCA and 840 controls.

The inclusion criteria follow. Cases included newly admitted cases of pathologically-confirmed CCA diagnosed between September 1, 2012, and July 31, 2014, at Srinagarind University Hospital. We included primary adenocarcinoma of the biliary tree, excluding the gallbladder or ampullary carcinomas. Among the CCAs, we excluded the rare variants; i.e., clear cell and spindle cell types and the mixed type (cholangiocellular carcinoma) which arise from the bile ductule and account for < 3% of cases. The included cases were sub-grouped into:

- •

The papillary carcinoma group with gross or microscopic evidence of invasive IPNBs.

- •

The group without evidence of IPNBs, non-papillary-, or tubular carcinoma.

The latter two groups were further divided into the ICC or ECC group.

The four controls were individually-matched with each case by sex, age (within five years), and date of admission (within three months). The controls were selected from among patients admitted between September 1, 2012, and July 31, 2014, to the Department of Otolaryngology, Ophthalmology, Rehabilitation, and Orthopedics, at Srinagarind University Hospital. The controls had no history of hepatobiliary disease or any other malignancy; as determined by reviewing the medical records.

Both the cases and controls:

- •

Were able to speak and understand Thai.

- •

Had sufficient cognitive function to provide reliable information.

- •

Signed the informed consent before participating in the study.

The factor of interest was the number of PZQ treatments, which was categorized into four groups:

- •

Never used.

- •

Used once.

- •

Used twice.

- •

Used more than twice.

The dosage used for treatment of opisthorchiasis in the endemic area is a single dose after meals (40 mg/kg body-weight).

Ethical considerationsThe Institutional Review Board (IRB), Office of Human Research Ethics, Khon Kaen University, reviewed and approved the study (HE591237).

Outcome variablesData were collected through face-to-face interviews conducted by a trained interviewer using a standardized pre-tested questionnaire. The variables included demographic data, detailed history of O. viverrini infection, tobacco use, alcohol use, family history of cancer, history of pesticide use, and number of PZQ treatments. The frequency of PZQ treatment was categorized into four groups (viz., never, once, twice and more than twice). The data were entered into a computer using the Online Medical Research Tools, OMERET, and were verified using STATA statistical software.

Statistical analysisThe demographic characteristics of the cases and controls are described. Frequency counts and percentages were used for the categorical variables. Multivariable conditional logistic regression was used to compute the adjusted odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs) in order to investigate the effect of the number of repeated PZQ treatments on CCA, while controlling for the effects of confounding variables. Enter elimination was used as the model fitting strategy. A likelihood ratio test was performed to assess the goodness-of-fit of the final model.

All analyses were performed using STATA version 10.0. All test statistics were two-sided, and a p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsThe majority of CCA cases and controls was male (60%). The mean age of cases and controls was 60.2 and 59.8 years, respectively. The mean difference of admission date between cases and controls was 27 (min = 0, max = 106) days. Most of both the cases and controls were married (80%). Almost all participants were Thai nationals and of the Buddhist faith.

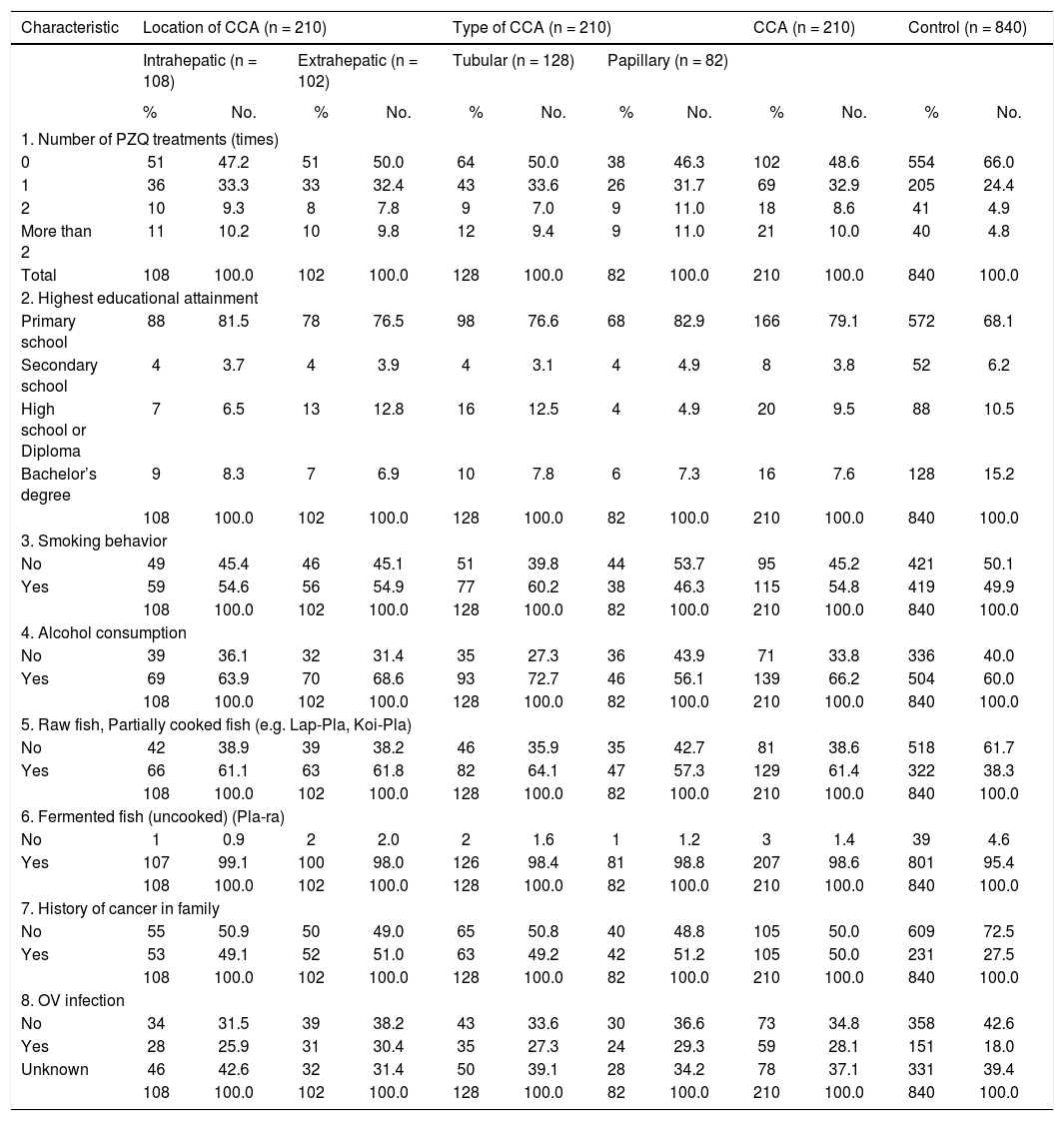

Of the 210 CCA cases, 108 were the intrahepatic type and 102 the extrahepatic type, according to location of the tumor. There was no statistically significant difference between these two groups in number of PZQ treatments, highest educational attainment, smoking behavior, alcohol consumption, raw fish consumption, fermented fish consumption, or family history of cancer. When CCA cases were differentiated according to the cell type of the tumor, 128 were tubular CCA and 82 papillary CCA. There were some differences in smoking behavior and alcohol consumption between the tubular and papillary type of CCA (Table 1).

Baseline characteristics by type of CCA and control groups.

| Characteristic | Location of CCA (n = 210) | Type of CCA (n = 210) | CCA (n = 210) | Control (n = 840) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrahepatic (n = 108) | Extrahepatic (n = 102) | Tubular (n = 128) | Papillary (n = 82) | |||||||||

| % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | |

| 1. Number of PZQ treatments (times) | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 51 | 47.2 | 51 | 50.0 | 64 | 50.0 | 38 | 46.3 | 102 | 48.6 | 554 | 66.0 |

| 1 | 36 | 33.3 | 33 | 32.4 | 43 | 33.6 | 26 | 31.7 | 69 | 32.9 | 205 | 24.4 |

| 2 | 10 | 9.3 | 8 | 7.8 | 9 | 7.0 | 9 | 11.0 | 18 | 8.6 | 41 | 4.9 |

| More than 2 | 11 | 10.2 | 10 | 9.8 | 12 | 9.4 | 9 | 11.0 | 21 | 10.0 | 40 | 4.8 |

| Total | 108 | 100.0 | 102 | 100.0 | 128 | 100.0 | 82 | 100.0 | 210 | 100.0 | 840 | 100.0 |

| 2. Highest educational attainment | ||||||||||||

| Primary school | 88 | 81.5 | 78 | 76.5 | 98 | 76.6 | 68 | 82.9 | 166 | 79.1 | 572 | 68.1 |

| Secondary school | 4 | 3.7 | 4 | 3.9 | 4 | 3.1 | 4 | 4.9 | 8 | 3.8 | 52 | 6.2 |

| High school or Diploma | 7 | 6.5 | 13 | 12.8 | 16 | 12.5 | 4 | 4.9 | 20 | 9.5 | 88 | 10.5 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 9 | 8.3 | 7 | 6.9 | 10 | 7.8 | 6 | 7.3 | 16 | 7.6 | 128 | 15.2 |

| 108 | 100.0 | 102 | 100.0 | 128 | 100.0 | 82 | 100.0 | 210 | 100.0 | 840 | 100.0 | |

| 3. Smoking behavior | ||||||||||||

| No | 49 | 45.4 | 46 | 45.1 | 51 | 39.8 | 44 | 53.7 | 95 | 45.2 | 421 | 50.1 |

| Yes | 59 | 54.6 | 56 | 54.9 | 77 | 60.2 | 38 | 46.3 | 115 | 54.8 | 419 | 49.9 |

| 108 | 100.0 | 102 | 100.0 | 128 | 100.0 | 82 | 100.0 | 210 | 100.0 | 840 | 100.0 | |

| 4. Alcohol consumption | ||||||||||||

| No | 39 | 36.1 | 32 | 31.4 | 35 | 27.3 | 36 | 43.9 | 71 | 33.8 | 336 | 40.0 |

| Yes | 69 | 63.9 | 70 | 68.6 | 93 | 72.7 | 46 | 56.1 | 139 | 66.2 | 504 | 60.0 |

| 108 | 100.0 | 102 | 100.0 | 128 | 100.0 | 82 | 100.0 | 210 | 100.0 | 840 | 100.0 | |

| 5. Raw fish, Partially cooked fish (e.g. Lap-Pla, Koi-Pla) | ||||||||||||

| No | 42 | 38.9 | 39 | 38.2 | 46 | 35.9 | 35 | 42.7 | 81 | 38.6 | 518 | 61.7 |

| Yes | 66 | 61.1 | 63 | 61.8 | 82 | 64.1 | 47 | 57.3 | 129 | 61.4 | 322 | 38.3 |

| 108 | 100.0 | 102 | 100.0 | 128 | 100.0 | 82 | 100.0 | 210 | 100.0 | 840 | 100.0 | |

| 6. Fermented fish (uncooked) (Pla-ra) | ||||||||||||

| No | 1 | 0.9 | 2 | 2.0 | 2 | 1.6 | 1 | 1.2 | 3 | 1.4 | 39 | 4.6 |

| Yes | 107 | 99.1 | 100 | 98.0 | 126 | 98.4 | 81 | 98.8 | 207 | 98.6 | 801 | 95.4 |

| 108 | 100.0 | 102 | 100.0 | 128 | 100.0 | 82 | 100.0 | 210 | 100.0 | 840 | 100.0 | |

| 7. History of cancer in family | ||||||||||||

| No | 55 | 50.9 | 50 | 49.0 | 65 | 50.8 | 40 | 48.8 | 105 | 50.0 | 609 | 72.5 |

| Yes | 53 | 49.1 | 52 | 51.0 | 63 | 49.2 | 42 | 51.2 | 105 | 50.0 | 231 | 27.5 |

| 108 | 100.0 | 102 | 100.0 | 128 | 100.0 | 82 | 100.0 | 210 | 100.0 | 840 | 100.0 | |

| 8. OV infection | ||||||||||||

| No | 34 | 31.5 | 39 | 38.2 | 43 | 33.6 | 30 | 36.6 | 73 | 34.8 | 358 | 42.6 |

| Yes | 28 | 25.9 | 31 | 30.4 | 35 | 27.3 | 24 | 29.3 | 59 | 28.1 | 151 | 18.0 |

| Unknown | 46 | 42.6 | 32 | 31.4 | 50 | 39.1 | 28 | 34.2 | 78 | 37.1 | 331 | 39.4 |

| 108 | 100.0 | 102 | 100.0 | 128 | 100.0 | 82 | 100.0 | 210 | 100.0 | 840 | 100.0 | |

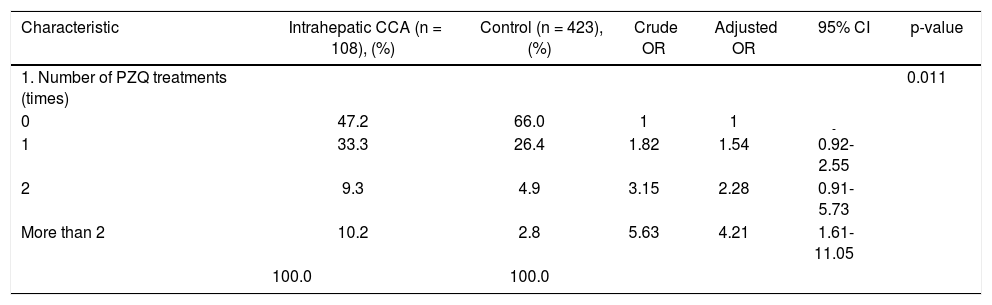

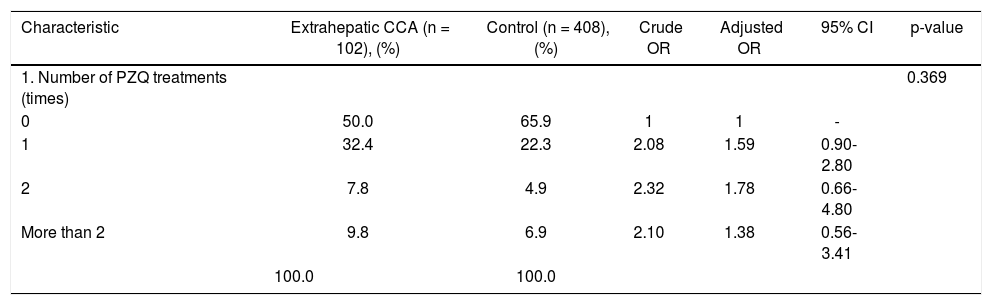

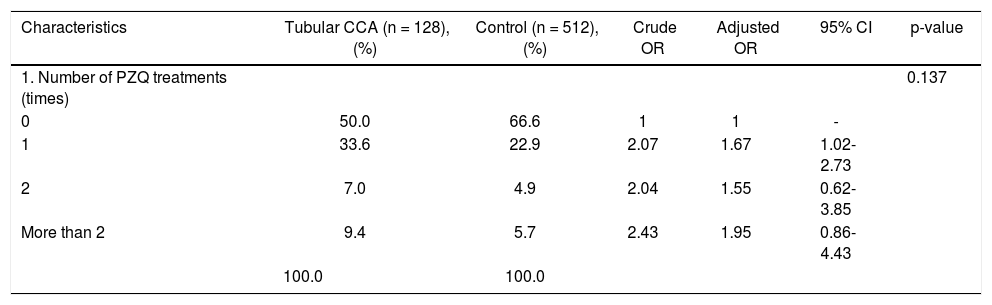

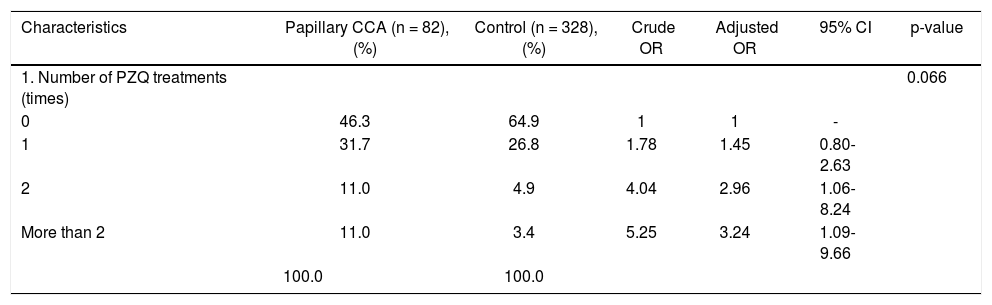

The results of association analysis between number of PZQ treatment and each type of CCA—according to the location and cell type of the tumor—are shown in tables 2-5. After adjustment for smoking behavior, alcohol consumption, history of cancer in family, and consuming raw freshwater fish, statistically significant associations were confirmed between intrahepatic or papillary CCA and repeated use of PZQ treatment. Using subjects who had never used PZQ as the reference group, the odds ratio for developing intrahepatic CCA for those who used PZQ once, twice and more than twice was 1.54 (95%CI:0.92-2.55 ), 2.28 (95%CI:0.91- 5.73), and 4.21 (95%CI:1.61-11.05), respectively (Table 2). The respective odds ratio of developing papillary CCA for those who used PZQ once, twice, and more than twice was 1.45 (95%CI: 0.80-2.63), 2.96 (95%CI:1.06-8.24), and 3.24 (95%CI: 1.09-9.66), respectively (Table 5). There was no association between the number of PZQ uses and developing extrahepatic or and tubular CCA (Tables 3-4).

Crude and adjusted ORs for Intrahepatic CCA and number of PZQ treatments.

| Characteristic | Intrahepatic CCA (n = 108), (%) | Control (n = 423), (%) | Crude OR | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Number of PZQ treatments (times) | 0.011 | |||||

| 0 | 47.2 | 66.0 | 1 | 1 | - | |

| 1 | 33.3 | 26.4 | 1.82 | 1.54 | 0.92-2.55 | |

| 2 | 9.3 | 4.9 | 3.15 | 2.28 | 0.91- 5.73 | |

| More than 2 | 10.2 | 2.8 | 5.63 | 4.21 | 1.61-11.05 | |

| 100.0 | 100.0 |

After adjustment for smoking behavior, alcohol consumption, history of cancer in family, and consuming raw freshwater fish.

Crude and adjusted ORs for extrahepatic CCA and number of PZQ treatments.

| Characteristic | Extrahepatic CCA (n = 102), (%) | Control (n = 408),(%) | Crude OR | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Number of PZQ treatments (times) | 0.369 | |||||

| 0 | 50.0 | 65.9 | 1 | 1 | - | |

| 1 | 32.4 | 22.3 | 2.08 | 1.59 | 0.90-2.80 | |

| 2 | 7.8 | 4.9 | 2.32 | 1.78 | 0.66-4.80 | |

| More than 2 | 9.8 | 6.9 | 2.10 | 1.38 | 0.56-3.41 | |

| 100.0 | 100.0 |

After adjustment for smoking behavior, alcohol consumption, history of cancer in family, and consuming raw freshwater fish.

Crude and adjusted odds ratios for Tubular CCA and number of PZQ treatments.

| Characteristics | Tubular CCA (n = 128), (%) | Control (n = 512), (%) | Crude OR | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Number of PZQ treatments (times) | 0.137 | |||||

| 0 | 50.0 | 66.6 | 1 | 1 | - | |

| 1 | 33.6 | 22.9 | 2.07 | 1.67 | 1.02-2.73 | |

| 2 | 7.0 | 4.9 | 2.04 | 1.55 | 0.62-3.85 | |

| More than 2 | 9.4 | 5.7 | 2.43 | 1.95 | 0.86-4.43 | |

| 100.0 | 100.0 |

After adjustment for smoking behavior, alcohol consumption, history of cancer in family, and consuming raw freshwater fish.

Crude and adjusted ORs for Papillary carcinoma and number of PZQ treatments.

| Characteristics | Papillary CCA (n = 82), (%) | Control (n = 328),(%) | Crude OR | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Number of PZQ treatments (times) | 0.066 | |||||

| 0 | 46.3 | 64.9 | 1 | 1 | - | |

| 1 | 31.7 | 26.8 | 1.78 | 1.45 | 0.80-2.63 | |

| 2 | 11.0 | 4.9 | 4.04 | 2.96 | 1.06-8.24 | |

| More than 2 | 11.0 | 3.4 | 5.25 | 3.24 | 1.09-9.66 | |

| 100.0 | 100.0 |

After adjustment for smoking behavior, alcohol consumption, history of cancer in family, and consuming raw freshwater fish.

Many studies including our previous study showed that repeated use of PZQ treatment was associated with an increased risk of developing CCA.10,14 Our current study established that this association is limited to intrahepatic or papillary CCA. Until now, there has been no study investigating the risk factors for CCA according to its location and cell type.

Although several studies using a hamster model have published evidence that PZQ treatment induces inflammation and oxidative and nitrative stress through O. viverrini antigen release,14 we cannot conclude that PZQ has a direct causative effect on cholangiocarcinogenesis. Thus, repeated use of PZQ is now believed to be a surrogate marker for the habit of eating raw fish rather than causing CCA itself.10,11O. viverrini infection, moreover, remains a major risk factor for CCA in Southeast Asia. The risk of developing CCA is indeed significantly increased in those who eat raw fish over against those who never eat raw fish. There is an incorrect understanding among many people about the use of PZQ. Some people think that if/when they get an O. viverrini infection, they should self-treat with PZQ. But then they proceed to eat raw fish again, become re-infected, and self-treat with PZQ again.6,15,16 The result is that the O. viverrini re-infection rate in the endemic area approaches 50%.16

Parasitic infection plays a major role in cholangiocarcinogenesis in the hamster model;17 however, it has been difficult to translate this observation to human cholangiocarcinogenesis because there are significant differences in bile duct caliber between hamsters and humans. Based on the evidence, parasitic infection causes greater harm to the small (intrahepatic) bile duct over against large one (the extrahepatic bile duct). Our findings agree with this explanation. We found, moreover, that repeated use of PZQ—a surrogate marker for parasitic infection—could increase the risk only of intrahepatic CCA. This is the first study to identify this relationship, according to the location of the tumor. We suggest that parasitic infection might not be a common risk factor in all types of CCA, and that risk factors other than parasitic infection— such as nitrosamines—should be studied further,18 particularly for extrahepatic CCA.

As we have mentioned, there is a difference between the pathogenesis of tubular vs. papillary CCA.12,13,19,20 Our findings indicate that only papillary CCA (malignant IPNB) was associated with repeated use of PZQ. Chronic biliary irritation may, therefore, play an important role in the development of intraductal papillary lesions rather than periductal inflammation. Moreover, the proportion of papillary CCA is higher in regions where liver flukes are endemic compared with regions where they are not.21–23 According to the concept of “biliary disease of the pancreatic counterpart”, IPNB—both benign and malignant—is included as a counterpart to intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas, whereas tubular CCA (also known as conventional CCA) is considered to be the counterpart of pancreatic adenocarcinoma.24,25 We, thus, suggest that future study regarding risk factors and carcinogenesis of these two entities should be performed separately.

The strengths of this study include:

- •

Its being the largest study enrolling pathologically-confirmed cases of CCA and the largest number of controls.

- •

Its demonstrating a dose-dependent response relationship between PZQ use and CCA.

- •

Its being the first to investigate the risk of repeated use of PZQ according to the types of CCA.

Limitations to the study include:

- •

Its relying upon data collected for another study,10 such that the sample size was based on different objectives.

- •

Its not having required immunohistochemistry to discriminate types of papillary tumor.20

In conclusion, this is the first study about the risk factors of CCA according to cell type and location. Papillary CCA (malignant IPNB) may be more likely from repeated OV infection than conventional (tubular) CCA. Since the respective pathogenesis of tubular and papillary CCA is different, studies regarding the risk factors of these two entities should be performed separately.

Abbreviations- •

CCA: cholangiocarcinoma.

- •

IPNB: intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct.

- •

PZQ: praziquantel.

This research used data collected for another study funded by the Royal College of Surgeons of Thailand.

AcknowledgementsThe authors thank (a) Professor Chomchark Chantrasakul for help obtaining funding assistance from the Royal College of Surgeons of Thailand, and (b) Mr. Bryan Roderick Hamman for assistance with the English-language presentation of the manuscript under the aegis of the Publication Clinic KKU, Thailand.