Hepatitis E virus (HEV) recently emerged in Europe as a cause of autochthonous acute hepatitis and a porcine zoonosis. European autochthonous cases almost exclusively involved viruses of genotype 3, subtype 3a being only recently reported in France, from farm pigs. We report an autochthonous human infection with a HEV related to subtype 3a in Southeastern France. A 55-year-old human immunodeficiency virus-infected man presented liver cytolysis in June 2014. HEV RNA was detected in serum and three months later, anti-HEV IgM and IgG were positive whereas HEV RNA was no more detectable in serum. No biological or clinical complication did occur. HEV phylogeny based on two capsid gene fragments showed clustering of sequences obtained from the case-patient with HEV-3a, mean nucleotide identity being 91.7 and 91.3% with their 10 best GenBank matches that were obtained in Japan, South Korea, USA, Canada, Germany and Hungria from humans, pigs and a mongoose. Identity between HEV sequence obtained here and HEV-3a sequences obtained at our laboratory from farm pigs sampled in 2012 in Southeastern France was only 90.2-91.4%. Apart from these pig sequences, best hits from France were of subtypes 3i, 3f, or undefined. The patient consumed barely cooked wild-boar meat; no other risk factor for HEV infection was documented. In Europe, HEV-3a has been described in humans in England and Portugal, in wild boars in Germany, and in pigs in Germany, the Netherlands, and, recently, France. These findings suggest to gain a better knowledge of HEV-3a circulation in France.

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) emerged in Europe during the past decade as a cause of autochthonous acute hepatitis and a porcine zoonosis.1 Main risk factors identified for infection were consumption of not thoroughly cooked food items derived from pigs and wild boars and contacts with these animals.1,2 This paradigm change on acute HEV infection epidemiology was accompanied by descriptions of chronic outcome in severely immunocompromized persons and other unexpected clinical features including neurological disorders.3 Four major HEV genotypes and 24 subtypes have been described.4,5 European autochthonous cases almost exclusively involved viruses of genotype 3.1,2 Various HEV-3 subtypes were described, only 3f, 3e and 3i being reported in France until we described recently HEV-3a sequences obtained from farm pigs sampled in 2012 in Southeastern France.2 We report here an autochthonous human infection with a HEV related to subtype 3a in Southeastern France.

Case ReportA 55-year-old French man, diagnosed in 1989 with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 infection acquired through injecting drug use, presented in June 2014 at our institution for his regular medical management. HIV RNA was < 40 copies/mL and CD4-cell count was 140 cells/mm3 on lamivudine/abacavir plus raltegravir. The patient was asymptomatic but liver cytolysis was revealed by biochemical testing performed systematically. Thus, alanine and aspartate aminotransferase levels were 380 and 567 IU/L, respectively. In addition, gammaglutamyltransferase was 868 IU/L and alkaline phosphatase level was 166 IU/L, whereas bilirubinemia was 8.7 μmol/L and prothrombin index was 90%. HEV RNA was detected in serum and viral load was determined to be 5.6 log10 copies/mL using an in-house real-time quantitative PCR assay, as previously described;6 HEV serology was not performed due to insufficient blood quantity available. Three months later, anti-HEV IgM and IgG were positive (Wantai assay, test/cut-off optical density ratio, 9 and 19, respectively) whereas HEV RNA was no more detectable in serum. No biological or clinical complication did occur.

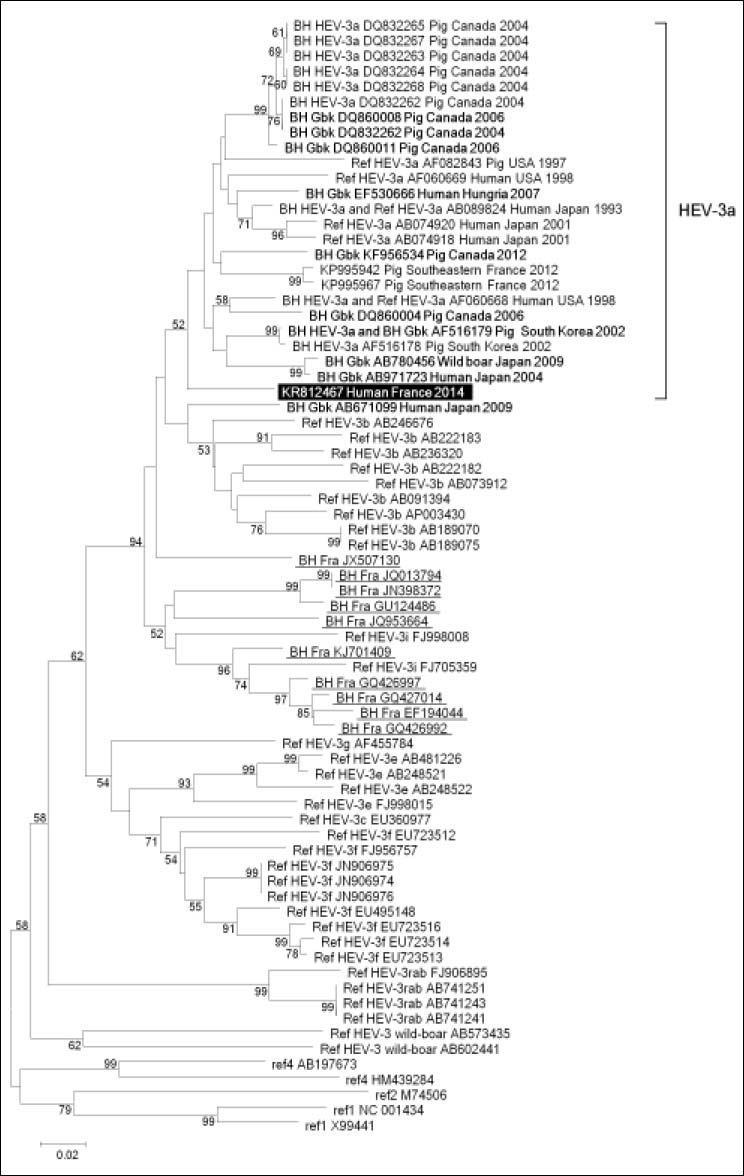

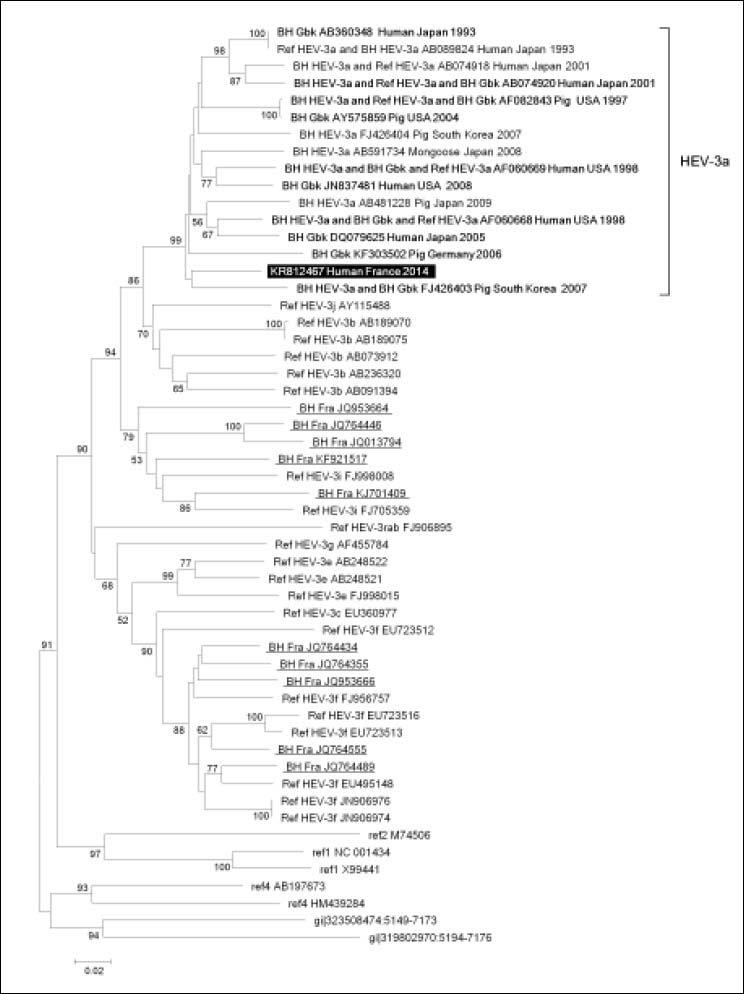

HEV phylogeny performed based on two 344- and 588-nucleotide long capsid gene fragments, which were recovered from the patient’s blood using previously described in-house PCR amplification and Sanger population sequencing procedures,6 showed clustering of sequences obtained from the case-patient with HEV of subtype 3a (Figures 1 and 2). Mean nucleotide identity was 91.7 ± 0.3% (range, 91.3-92.1) and 91.3 ± 0.7% (range, 90.5-92.5) for these two sequences with their 10 best hits in Gen-Bank, which were obtained in Japan, South Korea, USA, Canada, Germany and Hungria from humans, pigs and a mongoose. Identity between HEV sequence obtained here and HEV-3a sequences obtained at our laboratory from farm pigs sampled in 2012 in Southeastern France2 was only 90.2-91.4% (Figure 1). Apart from these sequences recovered from French pigs, best hits from France were not of subtype 3a but of subtypes 3i, 3f, or undefined. Mean nucleotide identity with these sequences was 86.2 ± 0.9% (range, 84.30–87.8%) and 84.3 ± 0.1% (range, 83.2– 85.8%) for the two capsid gene fragments. The patient did not travel abroad but, a few weeks before hepatitis onset, consumed barely cooked meat from a wild-boar hunted in the close area of Marseille, Southeastern France; the case-patient was not himself a hunter. No other risk factor for HEV infection was documented.

Phylogenetic tree based on 344-nucleotide long partial sequences corresponding to nucleotides 5,999-6,342 of open reading frame 2 (ORF2) of the HEV genome (GenBank accession no. AF082843). The HEV sequence obtained in our laboratory is indicated by a white bold font and a black background. The ten sequences with the highest BLAST scores were recovered from: (i) the NBCl GenBank nucleotide sequence database (labeled with BH (for Best BLAST Hit) and Gbk (for GenBank); indicated by a bold font); (ii) a curated set of2,255 sequences linked to France and downloaded from GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide) using “hepatitis E” AND (France OR French) as keywords (labeled with BH and Fra (for France); underlined); (iii) a set of 165 HEV-3a sequences identified based on a litterature search (labeled with BH and HEV-3a). These sequences (labeled with GenBank accession number, host, country and year of sample collection or sequence submission) have been incorporated into the phylogeny reconstruction, in addition to sets of ORF2 fragments from full-length HEV genomes of various HEV genotypes and subtypes that were downloaded from the Virus Pathogen Resource database (http://www.viprbrc.org) (labeled with Ref (for reference), HEV genotype and subtype, and GenBank accession number) and two HEV-3a sequences recently described in fecal samples from farm pigs.2 Nucleotide alignments were performed using the MUSCLE software (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/mus-cle/). The evolutionary history was inferred in the MEGA6 software (http://www.megasoftware.net/) using the Neighbor-Joining method and the Kimura 2-parameter method. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) is shown next to the branches. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree; the scale bar indicates the number of nucleotide substitutions per site. Bootstrap values > 50% are labeled on the tree.

Phylogenetic tree based on 588-nucleotide long partial sequences corresponding to nucleotides 6,533-7,120 of open reading frame 2 (ORF2) of the HEV genome (GenBank accession no. AF082843). Legend is the same than for Figure 1 except that no HEV-3a sequences were available from French farm pigs for this genome region.

HEV of genotype 3 is a well described causative agent of acute hepatitis among HIV-infected patients, and chronic infection can occur in some patients whose CD4-cell count is < 200 cells/mL.1 Here, HEV clearance occurred spontaneously within 3 months despite the patient’s CD4 cell count was 140/mm3.

Infection with HEV related to subtype 3a was the most remarkable finding in the present observation. HEV-3a strains circulate predominantly in Asia and America.4 It was inferred from phylogenetic analyses that they differentiated around the 1950s from the common ancestor of Asian subtypes imported from Europe, then reached America during the 1970s–1980s.4 In Europe, HEV-3a has been described in humans in England, 2011, and Portugal, 2012.7,8 This subtype was also reported in wild boars in Germany, and in pigs in Germany, in the Netherlands, and recently in Southeastern France.2,5 In contrast, HEV-3a was not described in humans in France, only nucleotide identity < 90% with HEV-3a being reported for sequences from an undefined subtype.9 Here, sequences from the case-patient were clustered with HEV-3a, although maximum identity was only 92.1–92.5% between these sequences. Besides, no clustering was observed for HEV sequences obtained here with any particular HEV-3a sequence, including those recently found in French pigs.2 The comprehensiveness of such molecular investigations might be limited by an insufficient number of sequences representative of HEV epidemiology that were obtained and released in public databases, and the likely still non negligible proportion of HEV infections that are overlooked in Europe.

The only risk factor identified for the case-patient was consumption of not thoroughly cooked wild boar meat. HEV-3a is not known to circulate among French wild boars, but this cannot be excluded as this subtype was detected in these animals in Germany.5 In addition, in studies conducted in Southern France, 7/285 wild boar livers tested HEV RNA- positive and seroprevalence was 23%.10 Moreover, consuming wild boar meat uncooked or undercooked was identified as a risk factor for HEV infection in Germany and France, and a higher HEV seropreva-lence was found for hunters among blood donors from southwestern France.1 Alternatively, other sources and modes of transmission may have been missed here. Taken together, these findings suggest to gain a better knowledge of HEV-3a circulation in France in humans, pigs and wild boars.

Competing Interests and FundingThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. The study was funded internally.