Background and rationale. The liver biopsy has been considered the gold standard for the diagnosis and quantification of fibrosis. However, this method presents limitations. In addition, the non-invasive evaluation of liver fibrosis is a challenge. The aim of this study was to validate the fibrosis cirrhosis index (FCI) index in a cohort of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/hepatitis C virus (HCV) coinfected patients, and compare to AST/ALT ratio (AAR), AST to platelet ratio index (APRI) and FIB-4 scores, as a tool for the assessment of liver fibrosis in coinfected patients.

Material and methods. Retrospective cross sectional study including 92 HIV-HCV coinfected patients evaluated in two reference centers for HIV treatment in the Public Health System in Southern Brazil. Patients who underwent liver biopsy for any indication and had concomitant laboratory data in the 3 months prior to liver biopsy, to allow the calculation of studied noninvasive markers (AAR, APRI, FIB-4 and FCI) were included.

Results. APRI < 0.5 presents the higher specificity to detect no or minimal fibrosis, whereas APRI > 1.5 presents the best negative predictive value and FCI > 1.25 the best specificity to detect significant fibrosis. The values of noninvasive markers for each Metavir fibrosis stage showed statistically significant differences only for APRI. In conclusion, until better noninvasive markers for liver fibrosis are developed and validated for HIV-HCV coinfected patients, noninvasive serum markers should be used carefully in this population.

The introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) increased life expectancy among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected individuals, allowing the development of cirrhosis and its complications in a significant number of patients, most often in cases of coinfection with the hepatitis B (HBV) or C (HCV) virus.1-3 Moreover, chronic liver diseases are responsible for 35 to 45% of deaths in HIV-infected patients.4

Liver biopsy has been considered the gold standard for the diagnosis and quantification of fibrosis. However, this method presents limitations, mainly regarding required number of samplings5 specimen size, and interobserver variability.6 Besides that, liver biopsy is not available in many health care settings, including the Brazilian Public Health System. Furthermore, although it is considered a safe procedure,7 it may be associated with major complications in 0.2 to 0.6% of cases.8

Thus, the non-invasive evaluation of liver fibrosis using accurate and accessible methods is of great importance. For this purpose, several laboratory measurements have been adopted as surrogate markers of liver fibrosis.

Serum marker panels include single assessment or combined indexes such as aspartate aminotransferase (AST, IU/L)/alanine aminotransferase (ALT, IU/L) ratio (AAR), AST-to-platelet ratio index (APRI), FIB-4 (includes age, platelets, AST and ALT) and Forns Index (includes age, platelets, gamma-glutamyl transferase, cholesterol). These markers may be attractive due to low cost and inclusion of widely available indirect markers of fibrosis.9 However, many studies show the limitations of APRI and have supported that its role should be primarily to exclude significant fibrosis.10–12 This appears to apply to HIV/HCV coinfected patients except those with low CD4 cell count.13 Whereas the performance of panels like HGM-3 (a panel of five serum markers including platelets, alkaline phosphatase, hyaluronic acid, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 and hepatocyte growth factor) and FibroMeter (includes age, sex, alpha-2-macroglobulin, platelets, AST, hyaluronic acid, prothrombin index and urea) shows to be superior, but these panels include some non-routine tests that may be expensive and not widely available.9 In addition, they still need additional external validation before to stablish their predictive accuracy.9

A new index called FCI was proposed to evaluate monoinfected HCV patients, and it was not validated yet for coinfected HIV/HCV patients.14 Therefore, the aim of this study was to validate the FCI index in a cohort of HIV/ HCV coinfected patients, and compare to AAR, APRI and FIB-4 scores as a tool for the assessment of liver fibrosis in coinfected patients.

Material and MethodsThis is a pooled analysis of two cross-sectional studies described elsewhere15,16 including HIV-HCV coinfected patients evaluated in two reference centers for HIV treatment in the Brazilian Public Health System in southern Brazil.

The inclusion criteria were HCV treatment-naïve patients with no evidence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection (negative for hepatitis B surface antigen), who underwent liver biopsy due to, for instance, evaluation of viral hepatitis, opportunistic disease or abnormality of liver tests, and had available laboratory data, obtained in the 3 months prior to liver biopsy. These data allow to calculate noninvasive markers (AAR, APRI, FIB-4 and FCI). Chronic HCV infection was defined as a positive serological test for HCV by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with a positive reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for HCV RNA. HIV infection was diagnosed by ELISA with a confirmatory western blot. The interpretation of liver biopsy specimens was based on Metavir fibrosis score17 and clinically significant fibrosis was defined as having a Metavir fibrosis score ranging from 2 to 4. The AST/ALT ratio was calculated and the cut-off ≥ 1.0 was used to detect cirrhosis.18

- •

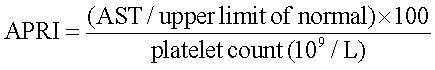

The APRI was calculated as:19

APRI < 0.5, no or minimal fibrosis was assumed.

APRI > 1.5, patients were classified as having significant fibrosis (Metavir > F2).20

- •

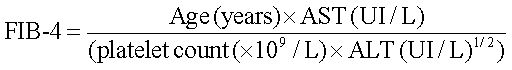

The FIB-4 score was based in the Sterling formula:

FIB-4 < 1.45, no or minimal fibrosis was assumed.

FIB-4 > 3.25, patients were classified as having significant fibrosis.21

- •

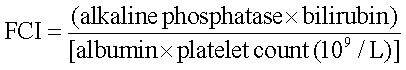

The FCI was calculated as following:

FCI < 0.13, patients were classified as having no or minimal fibrosis;

FCI > 1.25, patients were considered as having cirrhosis.14

Haematological and biochemical analyses were obtained from the patients’ records or electronic databases.

Performance of the scores was assessed by calculating the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and the area under the curve (AUC) and standard errors (SE) for the ROC curve were calculated according to Hanley and McNeil.22 Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were compared using cut-offs previously established. ANOVA was used to compare result values of the noninvasive fibrosis markers for each stage of Metavir Score seen in liver biopsy. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). This study was submitted and approved by the local Research Ethics Committee.

All quantitative data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise stated. Differences between groups were determined using the Student t-test for continuous variables and the χ2 test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables.

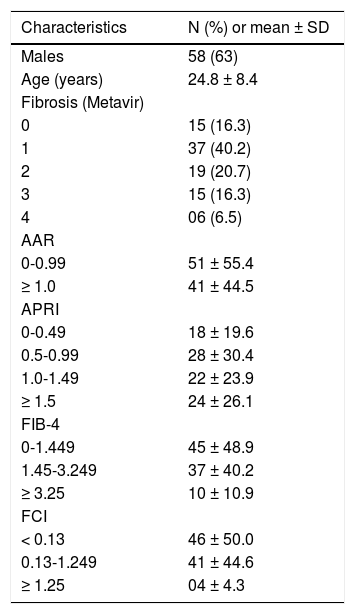

ResultsThe characteristics of 92 HIV/HCV coinfected patients regarding sex, age, grade of fibrosis and the distribution of the patients according to different cut-offs are described in the table 1. Fifty-eight (63%) were men and 47% being under 40 years-old. Most patients were on HAART therapy. Overall, 22.8% of the patients had advanced fibrosis (Metavir score F3-F4) detected by liver biopsy. Non-invasive AAR and FCI indexes suggested cirrhosis for 44.5 and 4.3% of patients, respectively. APRI and FIB-4 identified significant fibrosis in 26.1 and 10.9% of cases, respectively.

Characteristics of 92 HIV-HCV coinfected patients.

| Characteristics | N (%) or mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Males | 58 (63) |

| Age (years) | 24.8 ± 8.4 |

| Fibrosis (Metavir) | |

| 0 | 15 (16.3) |

| 1 | 37 (40.2) |

| 2 | 19 (20.7) |

| 3 | 15 (16.3) |

| 4 | 06 (6.5) |

| AAR | |

| 0-0.99 | 51 ± 55.4 |

| ≥ 1.0 | 41 ± 44.5 |

| APRI | |

| 0-0.49 | 18 ± 19.6 |

| 0.5-0.99 | 28 ± 30.4 |

| 1.0-1.49 | 22 ± 23.9 |

| ≥ 1.5 | 24 ± 26.1 |

| FIB-4 | |

| 0-1.449 | 45 ± 48.9 |

| 1.45-3.249 | 37 ± 40.2 |

| ≥ 3.25 | 10 ± 10.9 |

| FCI | |

| < 0.13 | 46 ± 50.0 |

| 0.13-1.249 | 41 ± 44.6 |

| ≥ 1.25 | 04 ± 4.3 |

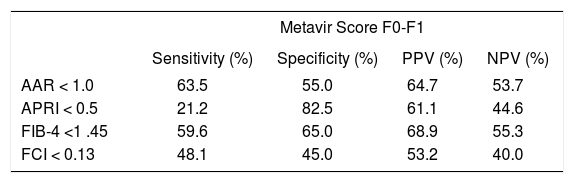

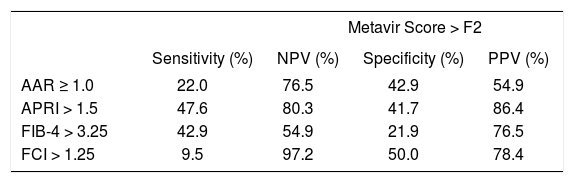

The accuracy of the different noninvasive markers to detect no or minimal fibrosis (equivalent to Metavir score F0-F1) vs. significant fibrosis (equivalent to Metavir score ≥ F2) is described in tables 2 and 3, respectively. It is shown that APRI < 0.5 presents the highest specificity (82.5%) among the study indexes to detect no or minimal fibrosis, whereas APRI cutoff of 1.5 presents the highest NPV (86.4%). FCI > 1.25 had the highest specificity (97.2%) to evaluate significant fibrosis, however with the poorest sensitivity.

Diagnostic properties of AAR, APRI, FIB4 and FCI to detect no or minimal fibrosis (Metavir score F0-F1) comparing to hepatic biopsy among HIV-HCV coinfected patients (n = 92).

| Metavir Score F0-F1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | |

| AAR < 1.0 | 63.5 | 55.0 | 64.7 | 53.7 |

| APRI < 0.5 | 21.2 | 82.5 | 61.1 | 44.6 |

| FIB-4 <1 .45 | 59.6 | 65.0 | 68.9 | 55.3 |

| FCI < 0.13 | 48.1 | 45.0 | 53.2 | 40.0 |

Diagnostic properties of AAR, APRI, FIB4 and FCI to detect significant fibrosis (Metavir score > F2) comparing to hepatic biopsy among 92 HIV-HCV coinfected patients (n = 92).

| Metavir Score > F2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (%) | NPV (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | |

| AAR ≥ 1.0 | 22.0 | 76.5 | 42.9 | 54.9 |

| APRI > 1.5 | 47.6 | 80.3 | 41.7 | 86.4 |

| FIB-4 > 3.25 | 42.9 | 54.9 | 21.9 | 76.5 |

| FCI > 1.25 | 9.5 | 97.2 | 50.0 | 78.4 |

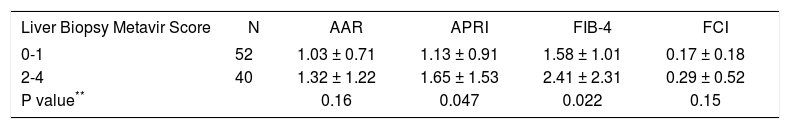

The mean values of APRI and FIB-4 indexes were statistically different among patients with non-significant (F0-F1) and significant (F2-F4) fibrosis according to Metavir score (Table 4). The results for FCI and APRI did not change markedly controlling for ALT.

DiscussionThe present study found no difference between AAR, APRI, FIB-4 and the new score FCI, which had not been previously validated to be used in HIV/HCV coinfected patients. In the same way, no indexes presented sensitivity or specificity good enough to detect the occurrence of significant fibrosis or cirrhosis. The unique index with a reasonable correlation with liver biopsy was the APRI score.

Patients with HIV are commonly coinfected with HCV, which is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.11,23,24 Identifying those who have significant fibrosis has emerged as an important aspect of the management of these patients.11,23,24 Furthermore, liver biopsy may be associated with major complications8 becoming not justifiable in many cases, reinforcing the need of noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis.11

Although it is universally accepted that liver biopsy provides important information about the extent of the liver disease and is considered the gold standard for scoring fibrosis, some investigators contend that it is an imperfect procedure with some disadvantages and complications25,26 including its invasive nature, inadequate biopsy size, intra-and inter-observer variability, tissue fragmentation, cost, and low acceptance by most patients.27–29

This study has some limitations that should be taken into account in the interpretation of the results. The ALT level used to calculate the scores were based on a single measure at the time of biopsy. It is known that HCV patients may have fluctuations in and out of the normal range30 that could modify the scores using ALT. Additionally, this study defined normal ALT based in the new cutoff values (30 U/l for men and 19 U/l for women),31 whereas the original study of APRI defined normal AST as 45 IU/l.19,20 Some authors found a difference in the performance of the APRI according to CD4T-cell count,13 concluding that the APRI score is a simple model that may be utilized to predict significant fibrosis in some patients with HCV/HIV coinfection, although it appears to be less accurate in coinfected patients with low CD4 counts. It must be emphasized that this finding was not corroborated by other authors.32 The same authors13 also found that FIB-4 score performed well in coinfected patients regardless of CD4 count.

Paesa, et al.12 evaluated APRI and Forns indexes in predicting significant fibrosis in coinfected patients. These authors evaluated 60 HCV infected patients (33 coinfected with HIV) and concluded that these models do not avoid the need for liver biopsies. Moreover, more than a half of the evaluated patients were not appropriately classified according to findings on liver biopsy and sensitivity and NPV were very low. Tural, et al.33 evaluated the clinical utility of three biochemical indexes, APRI, Forns, and FIB-4 for predicting liver fibrosis in a cohort of HIV/HCV coinfected patients. They found that advanced liver fibrosis could be ruled out with the lowest cutoff value, which gave a sensitivity of 79 to 94% and a NPV of 87 to 91%; whereas advanced liver fibrosis could be ruled in with a specificity of 90 to 96% and a PPV of 63 to 73%.

One common feature in the published studies is the ability of these biochemical tests to exclude significant or advanced liver fibrosis rather than rule them in. On the other hand, the low PPV and sensitivity of the tests, mainly in ruling in advanced fibrosis, prevent their use in clinical practice for identifying those patients in whom intensive screening for complications of cirrhosis should be implemented.

In the study of Ahmad, et al.,14 the FCI was developed to be used in HCV monoinfected patients, and showed better performance for discriminating between fibrosis stages as compared to AAR, APRI and FI (area under the ROC curve for predicting F0-F1 stage for FCI was 0.932). Moreover, FCI showed better performance for predicting cirrhosis than above mentioned serum indexes (area under the ROC curve = 0.996).

It is a common thought that all panels are acceptable in predicting the presence of no or mild fibrosis, and the absence of advanced fibrosis. Meanwhile, the low or moderate agreement with liver biopsy and the low sensitivity in the detection of mild fibrosis indicate that liver biopsy continues to be required when the results of other methods are discordant.10–13,25,34,35 In terms of serum marker panels, when tests are developed specifically for use in HIV/HCV coinfection they appear to have superior performance compared to those developed for monoinfected patients.9

Since liver biopsy diagnosis is not 100% accurate either, one should take into consideration these non-invasive scores all together and liver biopsy result when drawing conclusion on fibrosis stage. Combining noninvasive tests may increase diagnostic accuracy for staging liver fibrosis in HCV infected patients, but this strategy remains to be validated in HIV/HCV coinfection.36

In this sense, and as other investigators have stated for the HIV-uninfected population,37–40 the prediction of the degree of fibrosis or cirrhosis through noninvasive markers in HIV-HCV coinfected patients is poor even when epidemiologic, clinical, radiologic, and laboratory information are combined. The sensitivity to predict cirrhosis was about 50% in our study.

The study of Vecchi, et al.41 evaluated non-invasive assessment of liver steatosis and fibrosis in HIV/HCV coinfected patients, comparing the performance of APRI and FIB-4 to TE. However, the lack of liver biopsy to exclude a superimposed non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (that may be underestimated by TE) is a limitation recognized by the authors.

Therefore, it is not possible at this time to recommend the use of FCI in coinfected HIV/HCV patients. Similarly, the other non-invasive fibrosis markers evaluated in the study did not show sufficient accuracy to be used with confidence in this population.

Recently, the transient elastography (TE) has been proposed to evaluate the liver stiffness and assess the degree of liver fibrosis with accuracy, and its application can provide an useful alternative tool in the noninvasive evaluation of the liver fibrosis in coinfected HIV/HCV patients.42,43 However, it is not possible to widely indicate the use of TE in the coinfected HIV/HCV patients because it is still not validated in this specific population.

In conclusion, untill better noninvasive markers for liver fibrosis are developed and validated in HIV-HCV coinfected patients, biochemical noninvasive serum markers should be used carefully in this population. Future research goals should include the development of new noninvasive markers to detect the extent of liver fibrosis and to follow disease progression.

Abbreviations- •

AAR: AST/ALT ratio.

- •

ALT: alanine aminotransferase.

- •

APRI: AST to platelet ratio index.

- •

AST: aspartate aminotransferase.

- •

AUC: area under the curve.

- •

ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

- •

FCI: fibrosis cirrhosis index.

- •

HAART: active antiretroviral therapy.

- •

HBV: hepatitis B virus.

- •

HCV: hepatitis C virus.

- •

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

- •

NPV: negative predictive value.

- •

PPV: positive predictive value.

- •

ROC: receiver operating characteristic.

- •

RT-PCR: reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction.

- •

SD: standard deviation.

- •

SE: standard errors

- •

SPSS: Statistical Package for Social Sciences.

None.