Alcohol use constitutes a severe public health problem, causing 4.7 % of global deaths every year [1,2]. The proliferation of traditional and new psychoactive substances, and multiple disparities in education, income, and healthcare access, have contributed to a rising burden of alcohol-related health consequences [3,4]. In consequence, Latin America has to face a significant burden of alcohol use disorder (AUD) and alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD). In 2021, the Global Burden of Disease study estimated a prevalence of cirrhosis due to ALD of 90.8 per 100,000 individuals aged over 20 years in Latin America, while the prevalence of AUD was estimated at 3.2 % [2,5]. These epidemiological estimations are particularly concerning as, despite various national efforts, the prevalence of ALD has been rising over the past few decades, especially among younger populations and women [6,7].

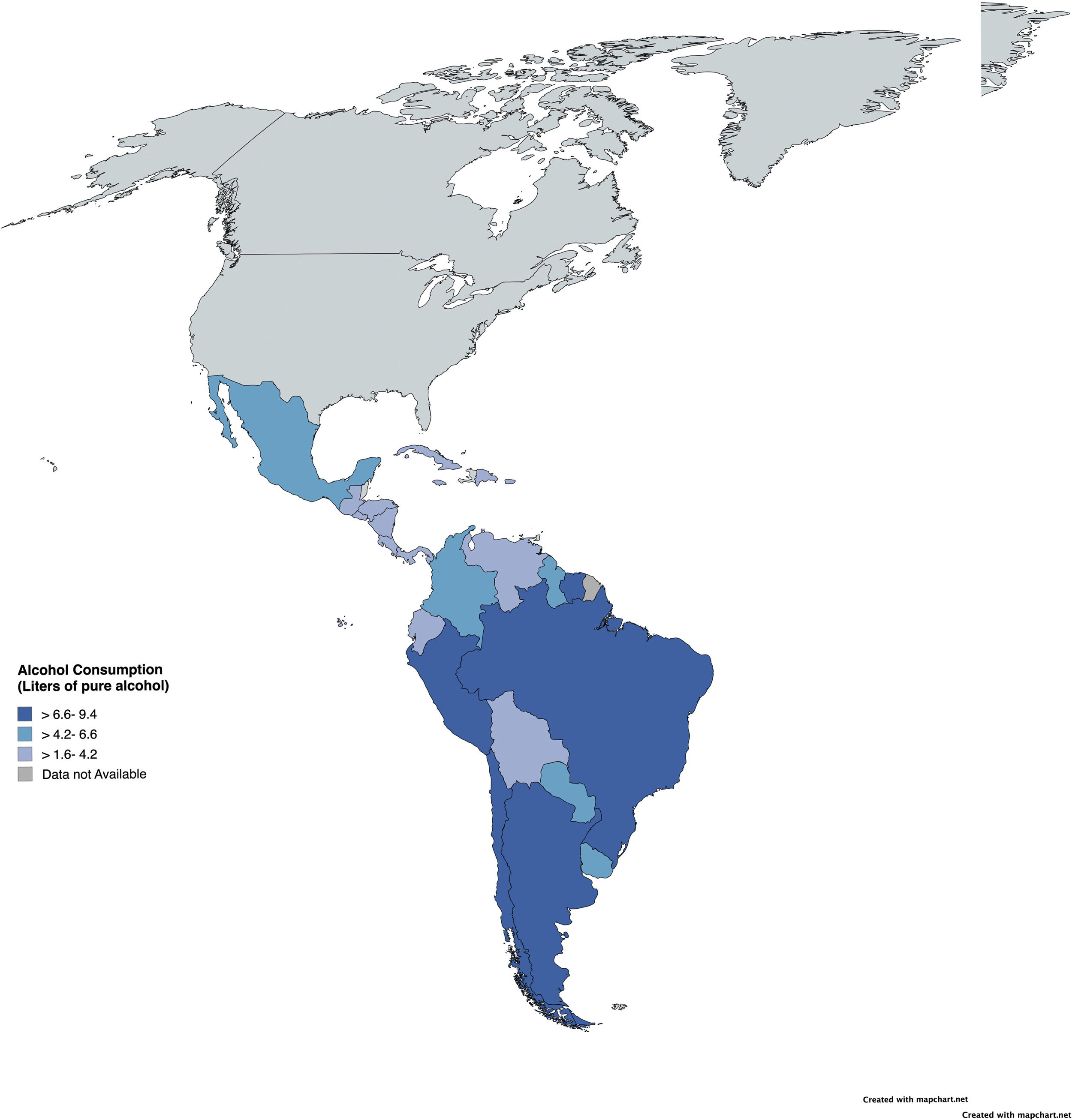

Latin America exhibits some of the highest rates of alcohol consumption globally. Indeed, in countries such as Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, Peru, and Colombia, over 66.8 % of the population over 15 years are current drinkers [8]. In addition, the estimated per capita alcohol consumption stood at 6.84 liters of pure alcohol in 2016, surpassing the global average [9]. It is also important to consider that homemade alcoholic beverages are widespread in rural areas of Latin America and often have high alcohol content. Thus, the exact amount consumed and the impact these beverages have on the population are poorly understood. As a result, while men have a higher prevalence of AUD, Latin America also has one of the highest rates of AUD among women globally, with particularly high rates in Colombia, Haiti, Peru, and Venezuela [8–10]. Additionally, low- and lower-middle-income countries in the region exhibit the highest AUD prevalence, even with lower alcohol consumption levels compared to higher-income countries, a well-described phenomenon called the alcohol harm-paradox [7,11].

Latin America also shows variations in drinking patterns (i.e., heavy episodic drinking, binge-drinking), being a significant concern. The estimated prevalence of binge-drinking is 21.3 % in the general population, rising to 40.5 % when considering only drinkers. These patterns are particularly pronounced in countries like Peru, where the prevalence of heavy drinking/binge-drinking reaches 26.4 % in the general population. The impact of these different drinking patterns is not entirely clear, raising greater concern, especially among young people [12]. In consequence, it is important to raise awareness among clinicians to detect alcohol use in clinical practice, even in occasional binge-drinking, and provide clear recommendations to moderate or cease alcohol consumption according to the baseline risk and comorbidities.

1Socioeconomic and cultural barriers in Latin AmericaLatin America is a complex region characterized by culturally and ethnically diverse populations, emerging economies, high levels of violence, and political instability, all contributing to varying degrees of inequality [13]. Additionally, the region's health systems are highly fragmented and segmented, creating significant challenges in delivering quality care to its population. According to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), 77 % of the population had health coverage in 2019, leaving a notable portion without access to healthcare services [14]. These socioeconomic disparities complicate access to healthcare, leading to variations in treatment outcomes.

Over the past three decades, several Latin American countries have introduced social and health sector reforms to achieve universal healthcare access and address social inequities. However, disparities persist, and health systems remain deeply fragmented [15–17]. In the following paragraphs, we will describe current problems and potential solutions to tackle ALD in Latin America.

2Screening for alcohol use in clinical practiceIn patients with ALD, identifying AUD is crucial for initiating appropriate therapies to achieve and maintain abstinence [18]. The diagnosis of AUD is based on DSM-V criteria; however, some screening tools can help identify patients with higher risk factors who may benefit from early intervention. Several self-report questionnaires are available for screening AUD in routine practice [19]. One option is a single-question screener: “How many times in the past year have you had 5 or more drinks in a day (for men) or 4 or more drinks in a day (for women)?”[20]. Additionally, widely used tools like the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Consumption (AUDIT-C) [21] offer a validated method for assessing alcohol misuse. The AUDIT-C, consisting of three questions about patients' drinking habits, is a shortened version of the full AUDIT. It provides a score ranging from 0 to 12, with a score of 4 or higher indicating risk in men and 3 or higher in women. Complementary biomarkers like phosphatidylethanol (PEth) can be used to follow-up abstinence in patients undergoing treatment [22]. The use of the AUDIT and self-reported alcohol consumption surveys in clinical settings often leads to under-reporting of alcohol use. Therefore, combining different alcohol assessment methods, including biomarkers, could improve sensitivity and diagnostic accuracy [23].

Alcohol is a leading factor that promotes the development or progression of other liver diseases beyond ALD, including etiologies such as Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), MetALD, Hepatitis B, and Hepatitis C [24–26]. Thus, after identifying hazardous alcohol use in individuals with chronic liver disease, it is pivotal to assess the presence of fibrosis. Currently, several non-invasive tools are available for this purpose, including serum biomarkers, liver stiffness measurement using vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE), ultrasound-based techniques, and magnetic resonance elastography [27].

The FIB-4 score is useful as a screening tool for fibrosis in patients with ALD. However, using this test alone results in false positives in 35 % of patients, leading to over-referrals. For those with an elevated FIB-4 score (greater than 1.3), a second test, such as VCTE or the Enhanced Liver Fibrosis (ELF) test, is recommended to improve fibrosis assessment. The ELF test, which measures hyaluronic acid, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1, and the N-terminal propeptide of collagen type III, is also a good option. The use of VCTE or ELF in patients with FIB-4 greater than 1.3 helps improve the identification of patients at risk of fibrosis and reduces false positives [28]. Regardless of the method used, recent evidence suggests that systematic screening for liver fibrosis can increase alcohol abstinence in the long term [29].

3Challenges in the management of ALD and AUD3.1Alcohol abstinence and management of AUDAchieving prolonged abstinence is by far the most crucial objective for patients with ALD. This measure significantly reduces disease progression, morbidity, and mortality in these patients, regardless of the stage of the disease [12]. However, achieving and maintaining abstinence is often challenging, as heavy alcohol consumption is associated with a high likelihood of relapse, even after both long and short periods of abstinence [30]. For instance, in patients who have experienced severe alcohol-associated hepatitis, more than 60 % relapse in the medium term, even though their intermediate and long-term prognosis is heavily influenced by whether they remain abstinent or not [30,31]. To effectively achieve abstinence, a comprehensive approach is essential. In this regard, support for addressing social issues and integration with a multidisciplinary team are particularly important in Latin America.

The management of AUD should be multifaceted and address all areas related to consumption patterns, offering an integrated approach to patient care [32]. Various psychosocial and behavioral therapies are beneficial in this process. Brief motivational interventions (lasting no more than 5–10 min) are recommended for all patients with AUD. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Motivational Enhancement Therapy are also valuable and should be considered. It is crucial to develop a framework for modifying alcohol intake, helping patients build resistance, change drinking habits, identify triggers that lead to relapse, and promote behaviors that replace alcohol consumption with alcohol-free alternatives [32].

3.2Pharmacological treatments for AUDIn addition to these therapies, pharmacological treatment is often necessary to manage symptoms and prevent relapse in patients with AUD [33]. Naltrexone and acamprosate, two FDA-approved medications for AUD, have not been specifically tested in ALD patients but are commonly used off-label in Child-Pugh A and B [34]. However, these drugs are scarcely available in Latin America, limiting the pharmacological options to disulfiram (which could cause hepatotoxicity and is not recommended in patients with advanced chronic liver disease) and baclofen. Baclofen, a GABA receptor agonist, has been tested as an anti-craving drug in severe ALD. It was evaluated in a placebo-controlled trial involving patients with cirrhosis and was found to prevent relapse and demonstrate a favorable safety profile [35]. In Latin America, baclofen appears to be a safe and available option. Other drugs such as topiramate, gabapentin, ondansetron, and varenicline may also be useful as anti-craving agents in AUD patients and are likely safe for those with ALD; however, further studies are needed to establish universal recommendations.

3.3New AUD treatments in the pipelineOther drugs have also been studied for the treatment of AUD [36]. Pregabalin, commonly used in various clinical contexts, demonstrates potential benefits primarily in patients with comorbid generalized anxiety disorder [37]. However, it presents a significant risk for dependence, particularly among individuals with co-occurring substance use disorders [38]. Aripiprazole, a partial dopamine D2 receptor agonist and 5-HT2A receptor antagonist, has been explored as a treatment option due to dopamineʼs role in motivation and reward pathways, which are implicated in substance abuse [39]. Despite a maximum daily dosage of 30 mg and metabolism via CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 enzymes, current evidence does not support its efficacy in treating AUD [40,41], though it may benefit patients with impulsive behavior [42]. Ondansetron, a 5HT3 antagonist, is hypothesized to regulate alcohol consumption severity through its action on the serotonergic system [43]. Although it undergoes hepatic metabolism, it remains a potential treatment for patients with ALD, but caution is warranted due to reports of liver toxicity. While initial studies suggested its efficacy in treating early-onset AUD [44] and certain genetic subtypes of heavy drinkers [43,45], recent findings challenge its utility in AUD management [46].

N-acetylcysteine, which modulates the glutamatergic system, is under investigation for its potential in AUD treatment and is one of the few options considered safe during pregnancy [47]. Although it may reduce cravings [48], the evidence remains inconclusive [49,50]. Spironolactone, a non-selective mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist commonly used in cirrhosis management, has also shown promise in reducing alcohol consumption in preclinical models and observational studies [51,52]. However, further research is necessary to establish its role in AUD treatment.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, primarily used for type 2 diabetes and obesity, have been found to influence brain regions involved in reward processing and addiction [53]. These agents have demonstrated efficacy in reducing alcohol intake and preventing relapse in preclinical models, without associated liver toxicity [54]. Although randomized controlled trials are needed to determine their potential as a novel treatment for AUD GLP-1 receptor agonists seem promising therapy for individuals with AUD and excess weight or type 2 diabetes mellitus [55].

Memantine, an NMDA receptor antagonist approved for Alzheimer's disease, has shown mixed results in AUD treatment, with preclinical studies suggesting a reduction in relapse risk, yet human trials remain inconclusive [56–58]. Emerging treatments, such as the ghrelin receptor GHSR inverse agonist PF-5190457 and the psychedelic psilocybin, have shown preliminary promise in promoting abstinence in AUD, although current evidence is insufficient to recommend their clinical use [59,60].

4Prevention of ALD from a public health perspectiveGiven the significant impact of ALD in Latin America, it is essential to actively limit and regulate excessive alcohol consumption to reduce its detrimental effects. The World Health Organization (WHO) has consistently called on countries to develop preventive policies and measures to curb alcohol consumption and its associated harm, though implementation levels vary globally. An ecological study on public health policies (PHPs) in Latin America revealed that the implementation of alcohol-related policies is highly heterogeneous across the region [9]. It also found that a higher number of public health policies were associated with lower mortality rates from ALD and a reduced prevalence of AUD. Among alcohol-related policies, a national plan to control the harmful consequences of alcohol, limiting the drinking age, driving‐related alcohol policies, and restrictions to alcohol access were associated with a lower risk of mortality due to ALD [9]. These findings were validated in an ecological study assessing the establishment of alcohol-related policies worldwide, observing a strong decrease in AUD and ALD prevalence in countries with a higher number of policies [61]. These findings aligned with the WHO SAFER framework that promotes the establishment of Best Buy alcohol-related policies and the Global Alcohol Action Plan 2022–2030 [61].

In addition to the aforementioned evidence, taxation and pricing policies have also shown an inverse relationship between taxation and cirrhosis mortality and have been effective in reducing alcohol consumption, especially in European countries [62–64]. Thus, although 90 % of Latin American countries have established taxes and pricing policies, a rise in prices or the implementation of a minimum unit pricing could decrease hospitalizations and deaths due to ALD [65]. It is important to notice that areas with high levels of unrecorded alcohol use could be less affected by pricing policies, making an individualized approach necessary to ensure adequate effectiveness of alcohol-related public health policies [10].

In conclusion, AUD and ALD present significant public health challenges in Latin America, exacerbated by high alcohol consumption rates, socio-economic disparities, and fragmented healthcare systems. Despite efforts to address these issues, ALD prevalence continues to rise, particularly among younger populations and women, underscoring the need for improved public health policies and comprehensive intervention strategies. Effective management of AUD and ALD requires a multifaceted approach, integrating screening, diagnosis, and treatment with culturally sensitive interventions and robust public health measures. Enhancing awareness, implementing stricter regulations on alcohol consumption, and expanding access to effective treatments are crucial steps toward mitigating the impact of these conditions and improving health outcomes across the region (Fig. 1).

FundingMA receives support from the Chilean government through the Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico (FONDECYT 1241450).