Despite the circulating levels of PTX3 were related to the severity of various diseases, there are no studies investigating its role in patients with liver cirrhosis. We aimed to study PTX3 levels in patients with liver cirrhosis.

Material and methodsA prospective cohort study included 130 patients hospitalized for acute decompensation of liver cirrhosis, 29 stable cirrhotic outpatients and 32 healthy controls evaluated in a tertiary hospital in Southern Brasil.

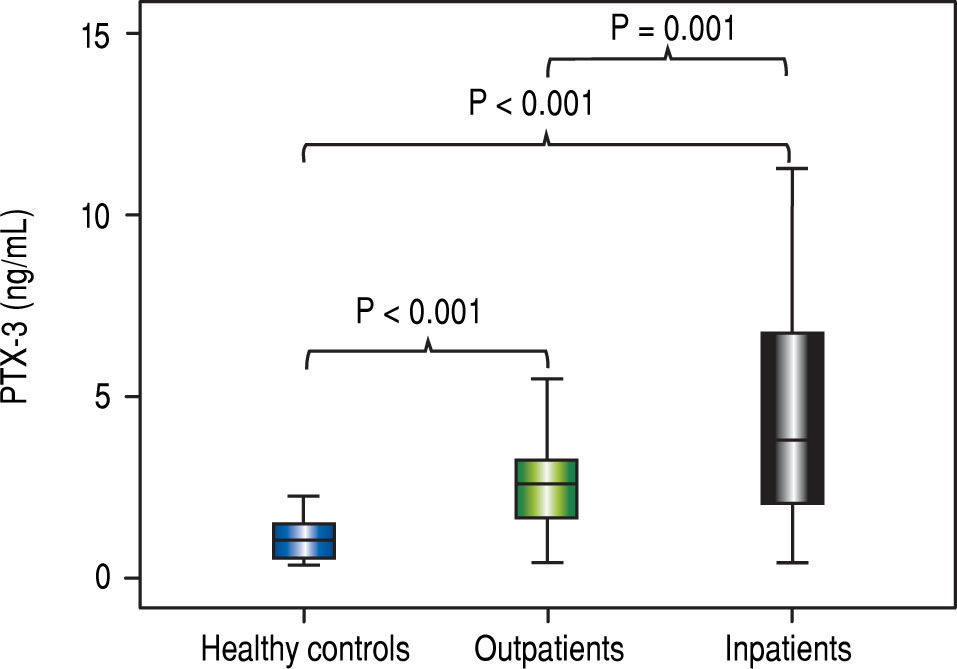

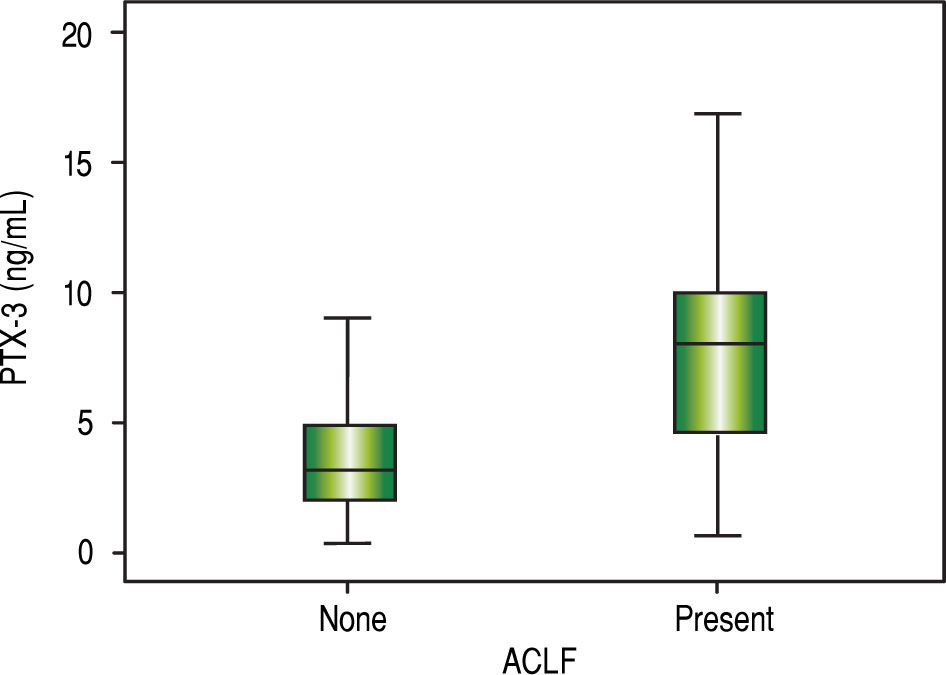

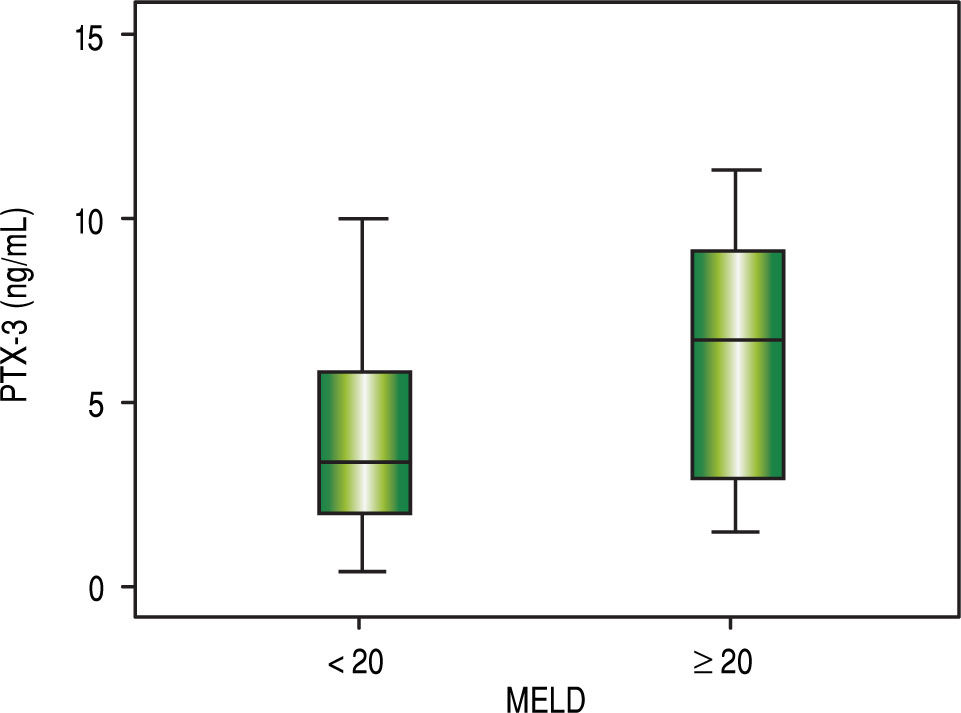

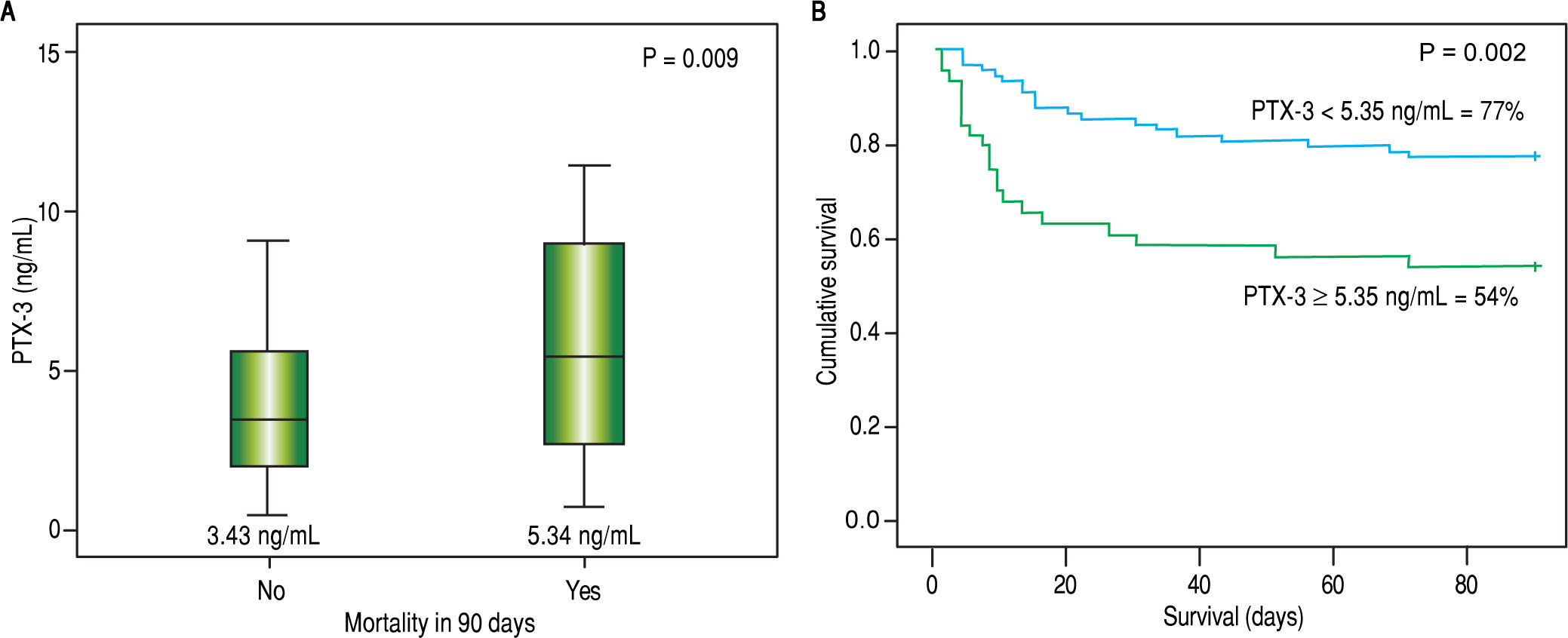

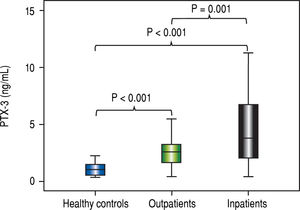

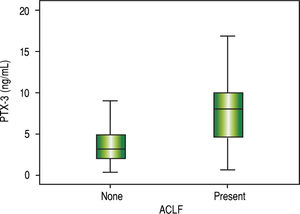

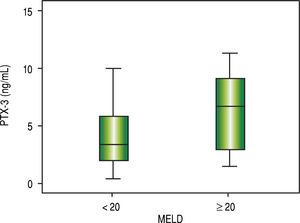

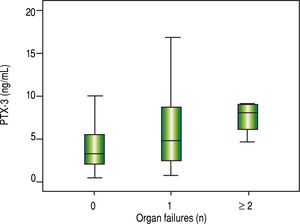

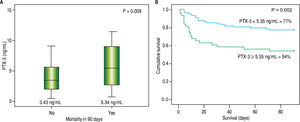

ResultsThe median PTX3 level was significantly higher in stable cirrhotic patients compared to controls (2.6 vs. 1.1 ng/mL; p < 0.001), hospitalized cirrhotic patients compared to controls (3.8 vs. 1.1 ng/mL; p < 0.001), and hospitalized cirrhotic patients compared to stable cirrhotic patients (3.8 vs. 2.6 ng/ mL; p = 0.001). A positive correlation was found between PTX3 and serum creatinine (r = 0.220; p = 0.012), Chronic Liver Failure -Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score (CLIF-SOFA) (r = 0.220; p = 0.010), MELD (r = 0.279; p = 0.001) and Child-Pugh score (r = 0.224; p = 0.010). Significantly higher levels of PTX3 were observed in patients on admission with ACLF (8.9 vs. 3.1 ng/mL; p < 0.001) and MELD score ≥ 20 (6.6 vs. 3.4 ng/mL; p = 0.002). Death within 90 days occurred in 30.8% of patients and was associated with higher levels of PTX3 (5.3 vs. 3.4 ng/mL; p = 0.009). The probability of Kaplan-Meier survival was 77.0% in patients with PTX-3 < 5.3 ng mL (upper tercile) and 53.5% in those with PTX3 ≥ 5.3 ng/mL (p = 0.002).

ConclusionThese results indicate the potential for use of PTX3 as an inflammatory biomarker for the prognosis of patients with hepatic cirrhosis.

Liver cirrhosis is the most advanced stage of chronic liver disease. It is characterized histologically by the presence of regenerative nodules. Its prevalence is estimated at 0.27% in the United States,1 and it is associated with multiple etiologies, most commonly ethanol consumption, chronic viral hepatitis B and C and diabetes mellitus.1,2 In-hospital mortality for disease decompensation is 9.1% in South Korea3 and is 25.0% after 30 days of admission in Brazil.4 Identifying patients with worse prognosis would facilitate early management of potentially severe cases. Several prognostic markers have been studied to identify mortality associated with decompensated cirrhosis, including the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score and its derivatives, Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure (ACLF) score, Interleukins 2, 6 and 8 (IL-2, IL-6 and IL-8, respectively), C-reactive protein (CRP) and even total leukocyte count.

Pentraxins are proteins formed by 5 monomers that form a ring in radial symmetry. They are a class of pattern recognition receptors. Among pentraxins, the main ones are pentraxin-3, CRP and serum amyloid P component. PTX3 is a long-chain pentraxin considered an acute phase marker produced mainly by endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells at the site of inflammation. It is also produced by macrophages, fibroblasts, neutrophils, epithelial cells, dendritic cells and other cell types both near and far from the inflammation site,5,6 Pentraxin production is influenced by certain inflammatory stimuli such as interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor alfa (TNF-α).7 It differs considerably from CRP in terms of expression patterns by affected organs. In particular, this is a short pentraxin mainly produced in the liver in response to IL-6.8

PTX3 has been recognized as an independent marker of inflammation associated with various disorders8,9 such as atherosclerosis, cancer, respiratory diseases and central nervous system diseases in which increased levels are related to the risk of the disease or its progression.10 However, according to our knowledge there are no studies that analyze its role in liver cirrhosis.

The aim of this study is to describe PTX3 levels in ambulatory patients and hospitalized patients with liver cirrhosis and their association with disease prognosis.

Material and MethodsSampleThis is a prospective cohort study with consecutive inclusion of patients with liver cirrhosis treated at the hepa-tology ambulatory department and admitted to the emergency service of a tertiary hospital in southern Brazil between January 2011 and January 2014 because of disease decompensation. Patients were excluded from the study because of insufficient clinical and laboratory data in the medical records, hepatocellular carcinoma that did not meet Milan criteria and refusal to participate in the study.

During routine outpatient or emergency admission, subjects were asked to participate and sign the free and informed consent form. A family member or guardian would authorize data collection if the patient had encepha-lopathy grades III or IV. Clinical and laboratory variables were collected from interviews and from the medical records. The following clinical variables were studied: age, sex, skin color, etiology of cirrhosis and presence of ascites. Laboratory variables collected on admission included serum creatinine, MELD, Child-Pugh and Chronic Liver Failure - Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (CLIF-SOFA) scores, total leukocyte count, serum sodium, platelet count, international normalized ratio (INR), albumin, CRP and total bilirubin.

The diagnosis of cirrhosis was established either histo-logically when liver biopsy was available or by a combination of clinical, imaging and laboratory data in patients with evidence of portal hypertension.

PTX3 assays were performed by Enzyme-Linked Im-munosorbent Assay with serum samples collected on admission or at an outpatient visit and stored in a freezer at -80 °C (ELISA; R&D Systems - Minneapolis, MN).

MethodsPatients were followed during hospitalization and 90-day mortality was assessed by telephone in case of discharge. The 90-day mortality rates did not include patients who underwent liver transplantation (because they were excluded from the study).

Individuals with suspected bacterial infection at admission underwent clinical examination to confirm the diagnosis and establish the primary source of infection. The diagnosis of infection was performed according to the criteria of the Center for Disease Control.11 Diagnostic paracentesis was performed for all patients with ascites present at admission. Hepatic encephalopathy was graded according to the criteria of West-Haven.12 If present, the precipitating factor was investigated and lactulose was administered with dose adjustment as needed.

The severity of liver disease was estimated by Child-Pugh13 and MELD scores14 calculated based on laboratory tests performed on admission. ACLF and CLIF-SOFA were defined as proposed by the European Association for the Study of the Liver-Chronic Liver Failure (EASL-CLIF).15

Statistical analysisNumerical variables with normal distribution were expressed as the mean and standard deviation (SD) and were compared using Student's t test. Numerical variables with non-normal distribution were expressed as medians and compared using the Mann-Whitney test. The normality of variable distribution was determined by the Kolmorogov-Smirnov test. Qualitative variables were represented by frequency (%) and chi-square test or Fisher's exact test were used when needed for analysis. Bivariate analyses were performed to compare cirrhotic individuals from outpatient visits with hospitalized patients. Bivariate analysis was performed to compare the mean levels of PTX3 in terms of the presence of cirrhosis complications at time of admission. Spearman correlation analysis was performed to compare the values of serum PTX3 to the laboratory variables and prognostic markers MELD, Child-Pugh and CLIF-SOFA. A cutoff point for the PTX3 was determined by Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. Survival probability was calculated using Kaplan-Meier method and differences in survival between groups were compared using the log-rank test.

All tests were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 22.0 (IBM SPSS statistics, Chicago, Illinois, USA). P values lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The study protocol was in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local research ethics committee under the number 252709.

RESULTSCasuistry analysisBetween January 2011 and January 2014, studied patients included 32 healthy controls, 29 subjects with liver cirrhosis treated at the hepatology ambulatory department and 130 cirrhotic patients admitted to the hospital for disease decompensation. Table 1 shows the demographic and epi-demiological characteristics of patients included in the study. The mean age of the controls was 41.8 ± 15.4 years and 78.0% were male. Individuals with cirrhosis had a mean age of 54.1 ± 11.7 years, 73.8% were male, 35.6% were Child-Pugh class C and the mean MELD score was 15.0 ± 6.2. Only seven patients underwent needle biopsy of the liver to diagnose cirrhosis. The etiology of cirrhosis was related to alcohol in 35.0%, alcohol and hepatitis C virus (HCV) in 22.5% and HCV only in 16.9%.

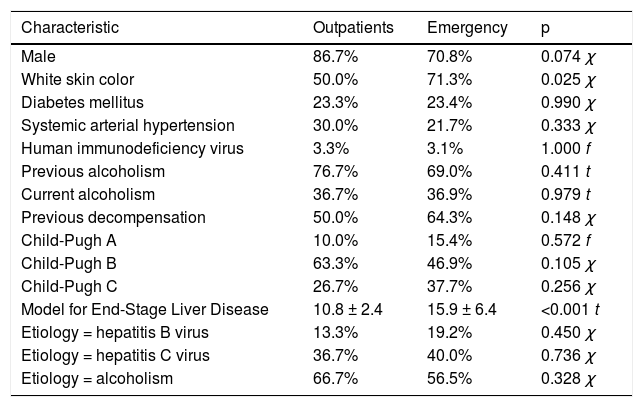

Demographic and epidemiological characteristics of the sample, according to the origin of the patients.

| Characteristic | Outpatients | Emergency | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 86.7% | 70.8% | 0.074 χ |

| White skin color | 50.0% | 71.3% | 0.025 χ |

| Diabetes mellitus | 23.3% | 23.4% | 0.990 χ |

| Systemic arterial hypertension | 30.0% | 21.7% | 0.333 χ |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | 3.3% | 3.1% | 1.000 f |

| Previous alcoholism | 76.7% | 69.0% | 0.411 t |

| Current alcoholism | 36.7% | 36.9% | 0.979 t |

| Previous decompensation | 50.0% | 64.3% | 0.148 χ |

| Child-Pugh A | 10.0% | 15.4% | 0.572 f |

| Child-Pugh B | 63.3% | 46.9% | 0.105 χ |

| Child-Pugh C | 26.7% | 37.7% | 0.256 χ |

| Model for End-Stage Liver Disease | 10.8 ± 2.4 | 15.9 ± 6.4 | <0.001 t |

| Etiology = hepatitis B virus | 13.3% | 19.2% | 0.450 χ |

| Etiology = hepatitis C virus | 36.7% | 40.0% | 0.736 χ |

| Etiology = alcoholism | 66.7% | 56.5% | 0.328 χ |

χ: Chi-square test. f: Fisher's exact test. t: Student's t test.

Outpatients and hospitalized patients with liver cirrhosis had similar clinical characteristics except for skin color, in which there was a higher proportion of individuals with white skin color among outpatients (50.0% vs. 71.3%; p = 0.025). These characteristics are shown in table 1. When comparing PTX3 levels between groups, it was observed that the cirrhotic outpatients had higher means compared to healthy controls (2.6 vs. 1.1 ng/mL; p < 0.001). Hospitalized cirrhotic patients had higher means compared both to healthy controls (3.8 vs. 1.1 ng/mL; p < 0.001) and to cirrhotic outpatients (3.8 vs. 2.6 ng/mL; p < 0.001) as can be seen in figure 1.

Correlation analysis of PTX3 with variables of interestThere was a positive correlation between serum levels of PTX3 and creatinine (r = 0.220; p = 0.012), MELD (r = 0.279; p = 0.001), Child-Pugh score (r = 0.224; p = 0.010) and CLIF-SOFA score (r = 0.225; p = 0.010). There was no correlation between PTX3 levels and total leukocyte count, serum sodium, platelet count, INR, albumin, CRP and total bilirubin.

Comparative analysis of serum PTX3 levels according to complications on admissionWhen comparing PTX3 levels in terms of the presence or absence of ACLF (Figure 2), it was observed that patients with ACLF showed higher PTX3 medians than those without ACLF (8.0 vs. 3.1 ng/mL; p < 0.001). When comparing PTX3 levels according to MELD score (Figure 3), it was observed that patients with MELD higher than 20 had higher median PTX3 levels compared to others (6.7 vs. 3.4 ng/mL; p = 0.002).

When comparing PTX3 levels according to Child classification, it was observed that individuals in Child class C had similar levels of PTX3 to the others (3.9 vs. 3.6 ng/mL; p = 0.559). When comparing PTX3 levels in terms of the presence of complications of cirrhosis, similar levels of PTX3 were observed in subjects presenting decompensation in infection (4.5 vs. 3.5 ng/mL; p = 0.197), ascites (4.0 vs. 3.6 ng/mL; p = 0.384) and grades III or IV encephalopa-thy (4.2 vs. 3.0 ng/mL; p = 0.247).

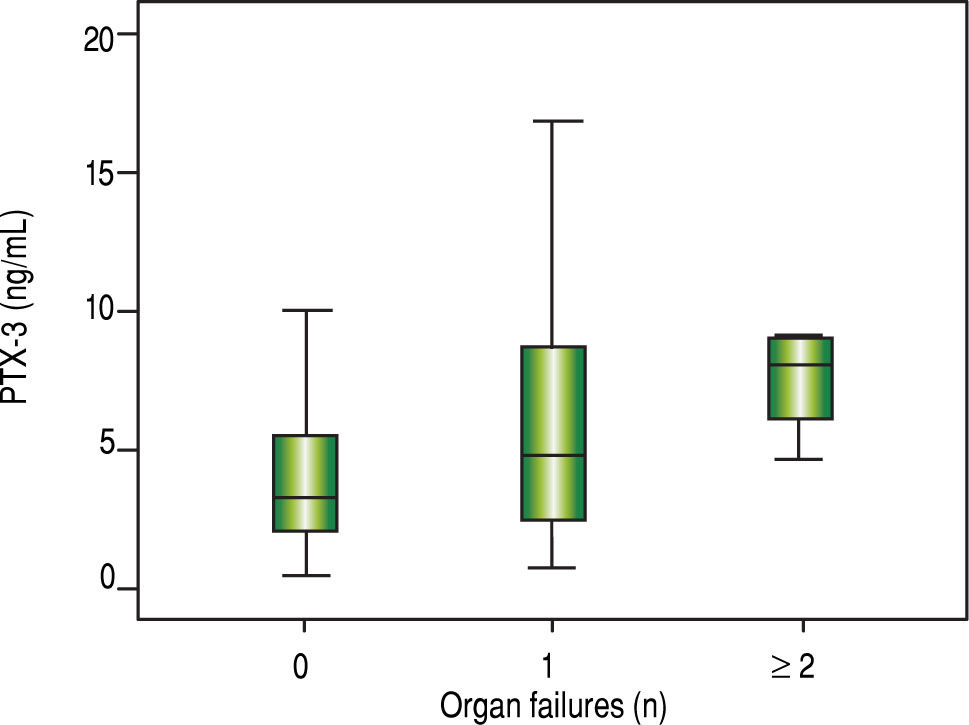

It was observed that the number of organ failures was associated with higher mean serum levels of PTX3 (Figure 4) as follows: none = 3.2 ng/mL; one = 4.7 ng/mL; two or more failures = 8.0 ng/mL (p = 0.006).

Survival analysis according to serum levels of PTX3Forty patients died within 90 days (30.8%). It was observed that patients who died within 90 days had higher serum levels of PTX3 on admission compared to those who survived (5.3 vs. 3.4 ng/mL; p = 0.009). Figure 5 shows the Kaplan-Meier curves associated with serum PTX3 levels. The probability of survival of patients with serum levels of PTX3 higher than or equal to 5.4 ng/mL was 54.0%, while those with serum levels lower than 5.4 ng/mL showed a 90-day survival rate of higher than 77.0% (p = 0.002).

DiscussionThis study has identified unprecedentedly higher PTX3 levels in cirrhotic outpatients compared to healthy controls as well as higher levels in cirrhotic patients hospitalized for disease decompensation compared to cirrhotic outpatients. The higher PTX3 levels in patients with acute decompensation in comparison to cirrhotic outpatients and healthy controls is consistent with the results of studies that showed elevated PTX3 levels in diseases with an inflammatory component that affect other organs such as acute myocardial infarction,16 chronic kidney disease,17 acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)18 and severe infectious diseases affecting patients in intensive care.19 Serum levels are positively correlated with disease severity.

This finding is corroborated by the positive correlation between serum PTX3 levels and the scores associated with severity of liver cirrhosis (MELD, Child-Pugh and CLIF-SOFA). In patients in intensive care with systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock, there was also a positive correlation between serum PTX3 levels and the clinical severity scores APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation) and SAPS II (Simplified Acute Physiology Score).19 PTX3 expression was evaluated serially in studies in patients with ARDS18 and in patients with SIRS, sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock.19 In both studies it was observed that PTX3 was the first plasma protein to rise, with a peak at approximately 7.5 h in patients with SIRS or infections in the clinical spectrum of sepsis. Levels declined in patients with ARDS after 24 h of intu-bation.18 CRP, a commonly used inflammation marker, had a later serum peak at approximately 24 h19 and remained elevated longer.18 Mauri, et al. performed a preliminary retrospective study if patients with ARDS that also showed a positive correlation between PTX3 levels and the number of organ failures,20 consistent with the results of this study.

In this study a positive correlation was also observed between serum PTX3 levels and 90-day mortality, consistent with the results of other groups that evaluated mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease, acute myocardial infarction and ARDS. In these studies, PTX3 proved to be an important and early predictor of mortali-ty.17,18 In patients with SIRS, sepsis, severe sepsis or septic shock, both PTX3 and IL-6 showed significant positive correlations with mortality.19 IL-6 was not assessed in this study. However, our group showed that IL-6 levels were positively associated with 90-day mortality (OR 1.002; 95% CI 1.000 - 1.004; p = 0.029).21

Many studies have compared the efficacy of PTX3 to CRP as a predictor of severity and mortality, given the widespread use of CRP for this purpose. The results as mentioned above show positive correlation when serum levels are compared without time reference. However, no correlation was apparent when considering the time to peak of each of these markers. In liver cirrhosis, however, CRP production is affected because it is synthesized almost entirely in the liver. This may compromise its utility as an inflammation biomarker in these patients.22,23 This might explain the absence of correlation between CRP and PTX3 in this study. However, Bota, et al. have not found statistically significant differences in CRP levels between intensive care patients with or without liver cirrhosis.24 Lazzarotto, et al. demonstrated that CRP levels are sensitive for diagnosis of infection and as predictors of 90-day mortality in patients with cirrhosis.25 Importantly, there is, to a lesser extent, production of CRP in inflamed tis-sues.26,27 This synthesis may be responsible for incomplete suppression of CRP levels even in patients with severe hepatic impairment.

There was also a positive correlation between serum levels of PTX3 and creatinine. Due to its high molecular weight (40.6 KD) and multimeric structure, PTX3 levels appear to increase as the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) decreases secondary to reduced clearance.17 The same phenomenon occurs with creatinine, it is therefore used as a marker of renal function. Numerous pathological conditions that lead to reduced GFR -such as sepsis, which generates numerous shunts in circulation and redistribution of blood volume; major bleeding, by an absolute reduction in blood volume; ascites, by third space volume retention and reduction of effective circulating volume-tend to increase serum creatinine. The complications of cirrhosis involve the above hemodynamic dysfunctions. One could imagine that this would be the reason for the positive correlation between serum levels of PTX3 and creatinine. However, more hemodynamic studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Although recently published studies present PTX3 as a marker of severity and/or mortality, little is known about its role in vivo in humans. Garlanda, et al. demonstrated in mice deficient in PTX3 that it has many functions including regulation of innate immunity against various microorganisms, discrimination of self- from non-self molecular patterns and tissue repair.27 Other studies showed that the initial function of PTX3 is protective.28 It participates in the recognition of harmful stimuli, migration of neutrophils to sites of infection and promotion of phagocytosis of bacteria by neutrophils,29 enhancement of nitric oxide production30 and increased expression of tissue factor.31 However, the prolonged persistence of stimuli can lead to overexpression of PTX3 and amplification of these inflammatory pathways,28 with resulting damage to the organism. Thus far, there are no known specific antagonists to the action of PTX3. Therefore, there are no data regarding blocking of this pathway and its repercussions.

Finally, the relevance of this study relies on the current difficulty in early determination of the severity of cirrhotic patients. Hemodynamic disturbances hinder the use of SIRS criteria;32 because the hyperdynamic circulatory state leads to tachycardia, beta-blocker use by many of these patients reduces the heart rate and can mask SIRS, hepatic encephalopathy can lead to tachyp-nea and hypersplenism caused by congestion of the portal system can lead to reductions in the number of circulating leukocytes.33 Added to these factors are the immunological changes associated with advanced liver disease, probably related to deficiencies in the complement system, which impair the elimination of op-sonized bacteria and increased bacterial translocation.34-36 This in turn predisposes patients with liver cirrhosis to infections. Furthermore, cultures of micro-organisms knowingly take at least 24 to 48 h to present results, which hampers their utility for diagnosing infectious complications. Therefore, it is important to find early markers of severity and mortality to guide appropriate treatment.

ConclusionsCirculating levels of PTX3 are increased in patients with liver cirrhosis, particularly those with acute decompensation. Serum PTX3 is related to the severity of the disease, the presence of ACLF and 90-day mortality. These results are promising and indicate a potential use for PTX3 as an inflammatory and prognostic biomarker for patients with liver cirrhosis.

Author ContributionsSchiavon LL designed the study. Bansho ETO and Silva TE were responsible for data collection. Morato EF, Pinheiro JT, Pereira JG, Wildner LM and Bazzo ML performed the pentraxin-3 sample processing. Schiavon LL, Narciso-Schiavon JL and Pereira JG analyzed the data and are responsible for the article as a whole. Narciso-Schia-von JL and Pereira JG wrote the paper and Dantas-Correa EB and Schiavon LL revised the manuscript.

Supportive FoundationsThis study was financed by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Técnológico (CNPq).

Institutional review board statementThe study was reviewed and approved by the Federal University of Santa Catarina Institutional Review Board under the number 252709.

Informed Consent StatementAll study participants or their respective legal guardians provided written informed consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data Sharing StatementNo additional data are available.