Prevalence and mortality of chronic liver disease have risen significantly. In end stage liver disease, the survival of patients is approximately two years. Despite the poor prognosis and high symptom burden of these patients, integration of palliative care is limited. We aim to assess associated factors and trends in palliative care use in recent years.

Materials and MethodsA Multicenter retrospective cohort of patients with end stage liver disease who suffered in-hospital mortality between 2017 and 2019. Information regarding patient demographics, hospital characteristics, comorbidities, etiology, decompensations, and interventions was collected. Two-sided tests and logistic regression analysis were used to identify factors associated with palliative care use.

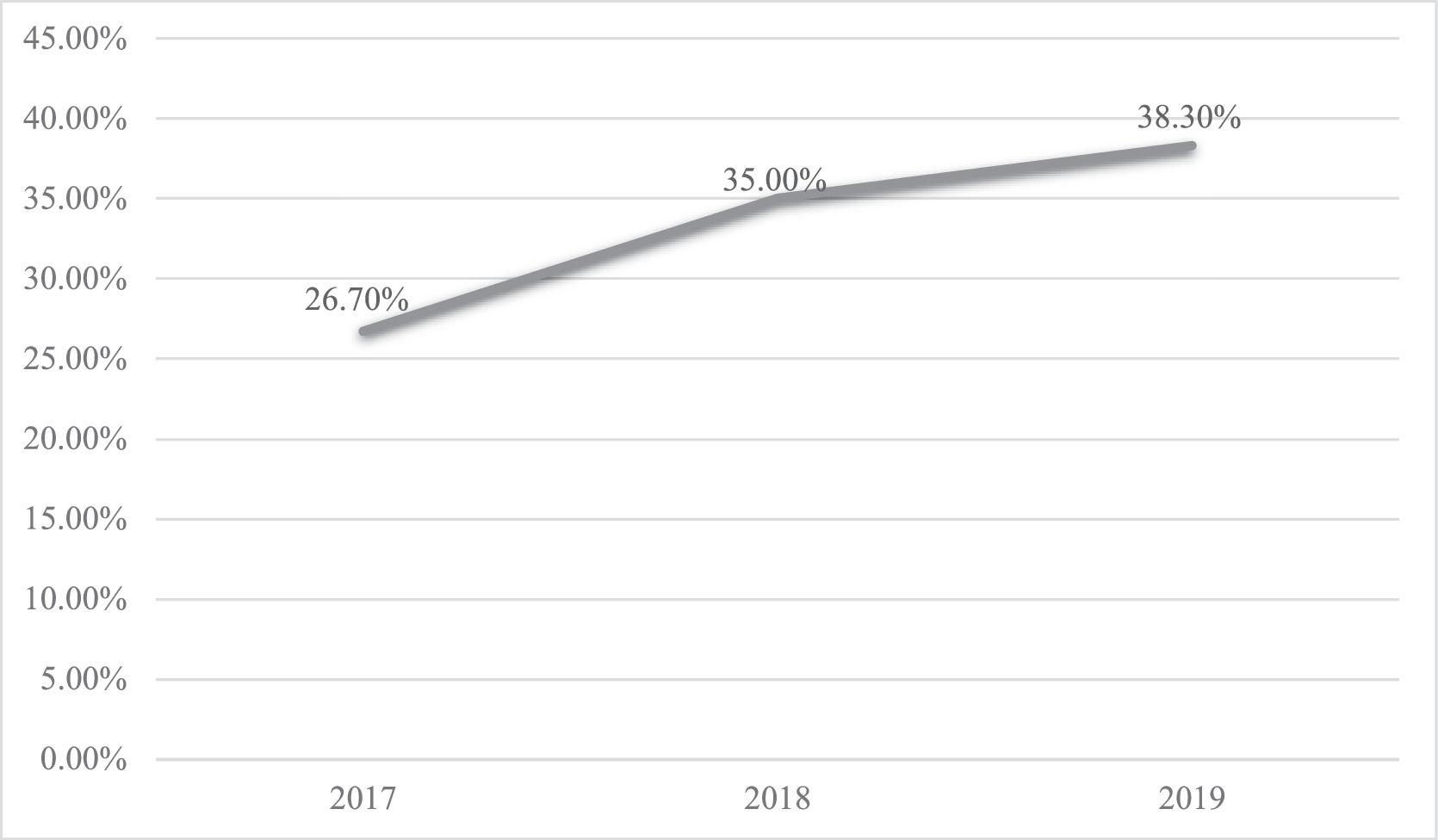

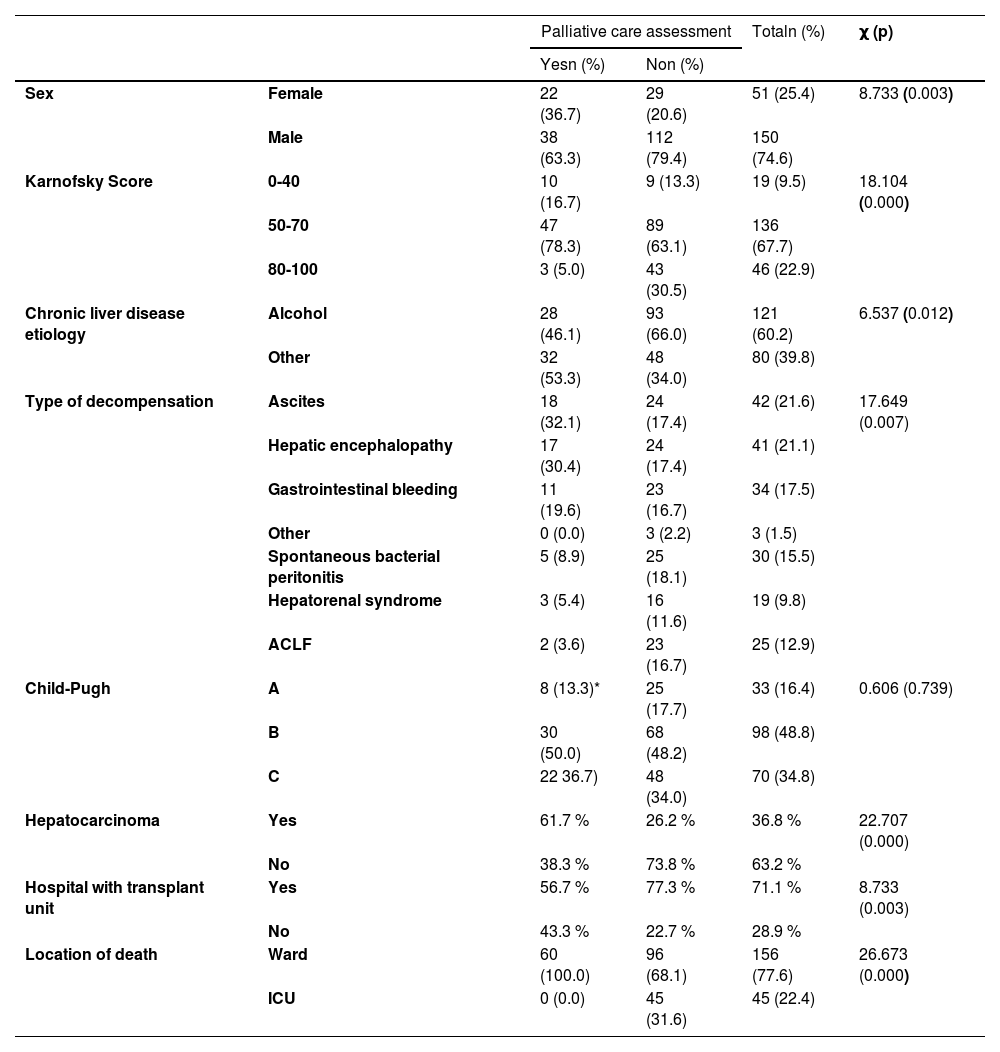

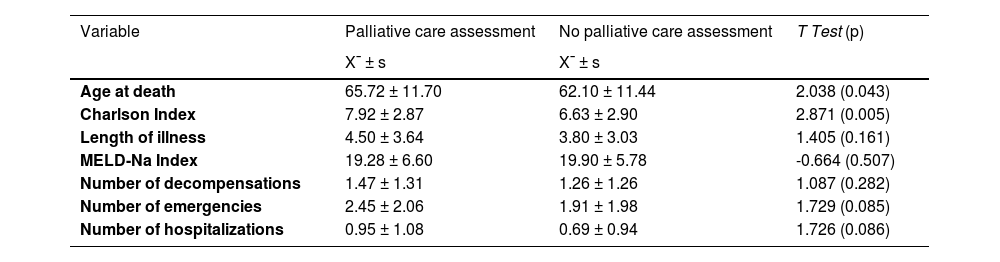

ResultsA total of 201 patients were analyzed, with a yearly increase in palliative care consultation: 26.7 % in 2017 to 38.3 % in 2019. Patients in palliative care were older (65.72 ± 11.70 vs. 62.10 ± 11.44; p = 0.003), had a lower Karnofsky functionality scale (χ=18.104; p = 0.000) and had higher rates of hepatic encephalopathy (32.1 % vs. 17.4 %, p = 0.007) and hepatocarcinoma (61.7 % vs. 26.2 %; p = 0.000). No differences were found for Model for End-stage Liver Disease (19.28 ± 6.60 vs. 19,90 ± 5.78; p = 0.507) or Child-Pugh scores (p = 0.739). None of the patients who die in the intensive care unit receive palliative care (0 % vs 31.6 %; p = 0.000). Half of the palliative care consultations occurred 6,5 days before death.

ConclusionsPalliative care use differs based on demographics, disease complications, and severity. Despite its increasing implementation, palliative care intervention occurs late. Future investigations should identify approaches to achieve an earlier and concurrent care model.

The prevalence and mortality of chronic liver disease have risen significantly worldwide in the last decades [1,2]. Portugal shows this same trend, with death from liver disease ranking 8th and being the European country with the highest mortality from hepatocarcinoma [3]. Typically, chronic liver disease progresses from a compensated phase to the emergence of one or more liver related decompensations, such as ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, or gastrointestinal bleeding, a phase designated as decompensated liver cirrhosis [4]. End stage liver disease (ESLD) is defined as advanced fibrosis of the liver with one or more liver related decompensations or liver related complications such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatorenal syndrome, hepatopulmonary syndrome, or hepatocarcinoma [4]. The survival of patients with ESLD is approximately two years, and the appearance of hepatocarcinoma can accelerate the course of the disease and worsen the prognosis [4]. In ESLD, liver transplantation is the only curative treatment. However, some patients are not eligible, and the scarcity of organs determines that only a few patients have access to this therapeutic strategy [5].

Despite the poor prognosis associated with ESLD and the high symptom burden of these patients, studies show that the integration of palliative care in ESLD is reduced and restricted, usually after exclusion from the liver transplantation list or on the last days of life [6–8]. In addition to symptomatic control, palliative care teams facilitate timely discussion of the care plan and treatment goals [9], rarely discussed in these patients [10,11]. They are also important in supporting caregivers with high physical and psychological burdens [12]. Nevertheless, several studies show patients’ misperception of palliative care, which continues to be regarded as synonymous with end-of-life, the emphasis of assistant physicians on a curative approach, and the reduced number of physicians in palliative care, which act as barriers to the early integration of palliative care in ESLD [9,13,14].

The growing research [15,16], the recognition of scientific societies through the publication of recommendations on the topic [17] and studies showing the benefit of palliative care intervention in the symptomatic improvement of patients with ESLD, may explain the growing trend in referring patients with ESLD to palliative care [18–20]. However, with most studies taking place in the United States [21,22], the existing data in Europe are still limited [23]. A previous study in Portugal found that the rate of referral to palliative care was less than 8 % [24].

The objectives of this study are to determine palliative care referral rates and patterns for patients who died with ESLD between 2017 and 2019 and to identify the clinical and patient factors associated with referral.

2Materials and Methods2.1Study design and patientsWe performed a retrospective cohort study of patients with ESLD who died in three Portuguese hospitals between January 1, 2017, and December 31, 2019. This convenience sample aims to represent different hospital types as it allows us to know the reality of a university center with a liver transplant unit, a district hospital with a very stablished liver center, and a local health unit with a stablished palliative care team. All of these hospitals simultaneously offer structured hepatology and palliative care services.

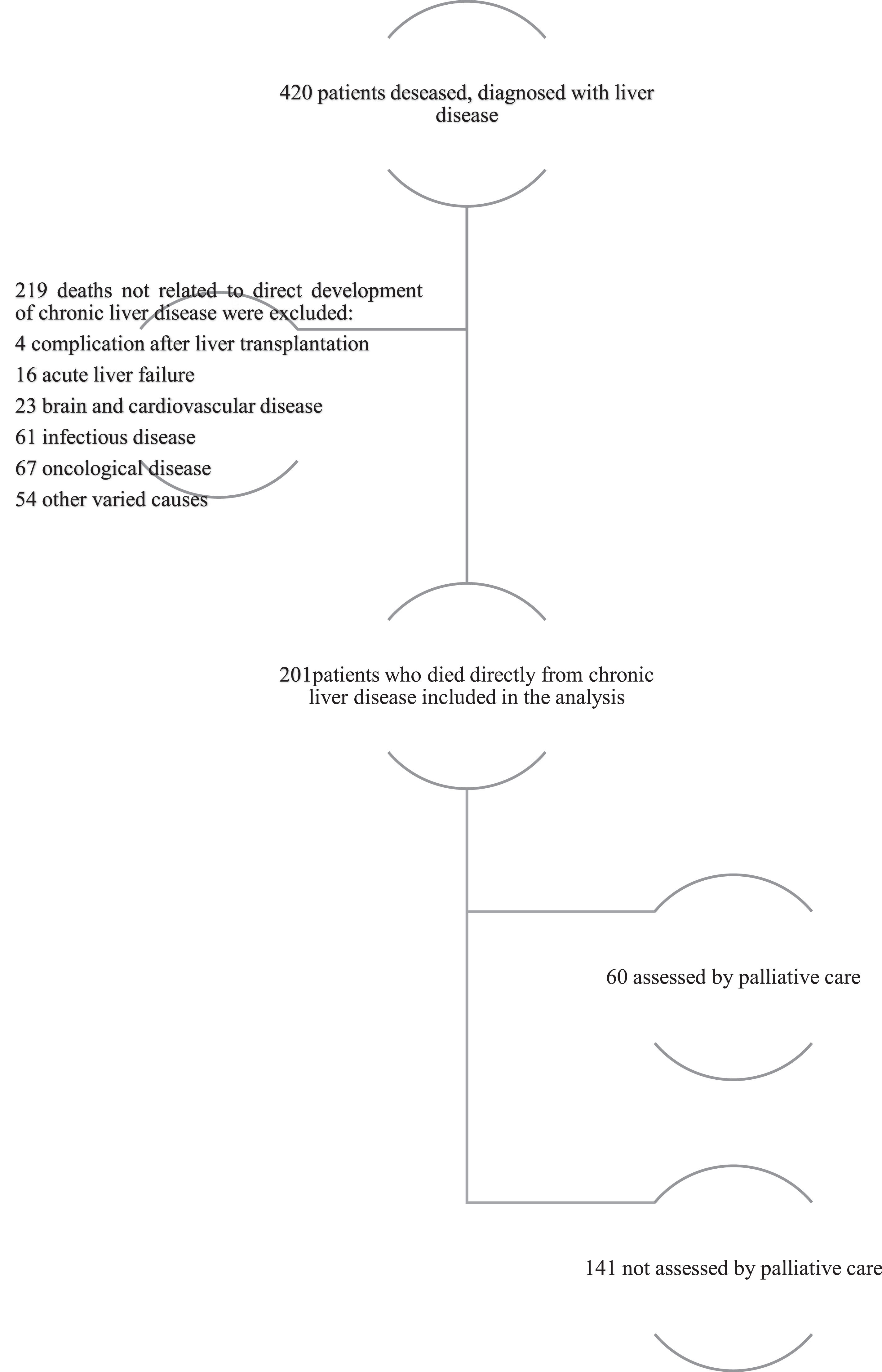

Patients were identified by screening the electronic medical record for the presence of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes for cirrhosis, chronic liver disease, and indicators of hepatic decompensation. Patients under 18 years old, patients who died from acute hepatic failure or due to liver transplant, and those with ESLD but who died from a cause unrelated to the evolution of ESLD were excluded. These criteria aimed to minimize selection bias and capture a broad scope of patients. The study was approved by each hospital's ethical commission.

2.2OutcomesThe primary outcomes of interest were referral to palliative care and predictors of use of palliative care. Secondary outcomes included the time between referral and death.

2.3VariablesData were collected using the hospital's digital information system. We collected patients’ characteristics that could impact outcomes: age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index [25], and Karnofsky Performance Scale [26]. Liver-specific variables included liver disease etiology, liver disease complications (ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatic encephalopathy, gastrointestinal bleeding, hepatorenal syndrome, acute-on-chronic liver failure [ACLF] and hepatocarcinoma), and liver disease severity (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD)-Na and Child-Pugh scores) [27,28]. Hepatocarcinoma was classified according to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system [29].

2.4Statistical analysesCategorical variables were specified as counts and percentages, and continuous variables were specified using mean and standard deviations when normally distributed and as medians and ranges otherwise. Comparisons between categorical variables were performed with Pearson's chi-square test or Fisher's exact test where appropriate, and comparisons between continuous variables were carried out using the Student's t-test for normally distributed variables or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test otherwise. Two-sided tests were used and were considered statistically significant when p-values were < 0.05. Logistic regression analysis was applied to identify factors associated with palliative care use, and a post hoc power analysis was carried out. Analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Mac (version 26).

2.5Ethical statementThe study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the Ethics Committee of Centro Hospitalar Universitário do Porto (2021.351;284-DEFI/299-CE), Centro Hospitalar Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro (3335/CE) and Unidade Local de Saúde de Matosinhos (131/CES/JAS). As a non-interventional study of deceased patients, the Ethics Committee waived written informed consent.

3Results3.1General characterization of the sampleBetween 2017 and 2019, 420 patients diagnosed with chronic liver disease died, of which 219 were excluded, leaving 201 patients for analysis (Fig. 1), granting a post hoc power analysis with a test power of 90 % and a type I error of 5 %.

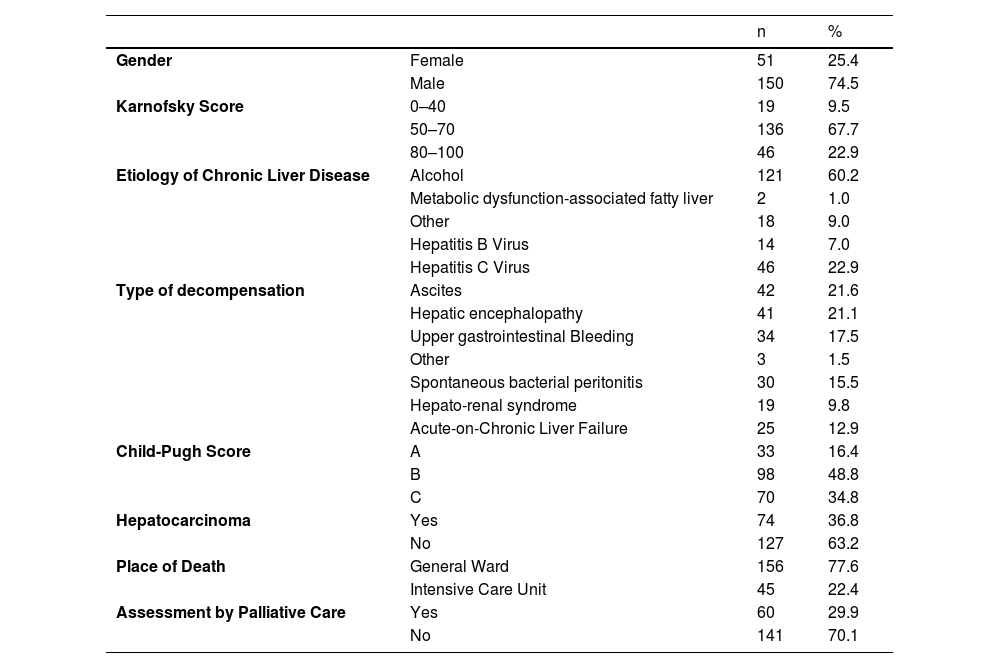

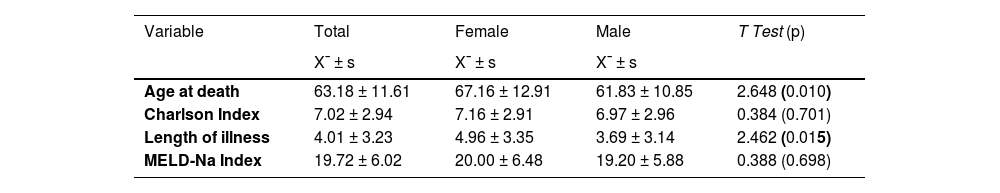

The general characteristics of this population are found in Tables 1 and 2. The mean age was 63.18 ± 11.61 years, with 50 % of patients being up to 63 years old and the majority of patients being male (74.5 %; n = 150). On average, these patients had a Charlson index of 7.02 ± 2.94, with a median of 7.00, and the majority had a Karnofsky functionality scale of 50–70 (67.7 %; n = 136). There are some comparative differences for the female gender (Table 2).

Characteristics of patients who died with advanced chronic liver disease between 2017 and 2019.

Characterization of age at death, Charlson index, length of illness and MELD-Na index by sex.

X¯ ± s – – mean ± standard deviation; T test (p) – Parametric test statistics (significance level) for comparing results between men and women.

Factors associated with referral to palliative care.

| Palliative care assessment | Totaln (%) | χ (p) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yesn (%) | Non (%) | ||||

| Sex | Female | 22 (36.7) | 29 (20.6) | 51 (25.4) | 8.733 (0.003) |

| Male | 38 (63.3) | 112 (79.4) | 150 (74.6) | ||

| Karnofsky Score | 0-40 | 10 (16.7) | 9 (13.3) | 19 (9.5) | 18.104 (0.000) |

| 50-70 | 47 (78.3) | 89 (63.1) | 136 (67.7) | ||

| 80-100 | 3 (5.0) | 43 (30.5) | 46 (22.9) | ||

| Chronic liver disease etiology | Alcohol | 28 (46.1) | 93 (66.0) | 121 (60.2) | 6.537 (0.012) |

| Other | 32 (53.3) | 48 (34.0) | 80 (39.8) | ||

| Type of decompensation | Ascites | 18 (32.1) | 24 (17.4) | 42 (21.6) | 17.649 (0.007) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 17 (30.4) | 24 (17.4) | 41 (21.1) | ||

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 11 (19.6) | 23 (16.7) | 34 (17.5) | ||

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.2) | 3 (1.5) | ||

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 5 (8.9) | 25 (18.1) | 30 (15.5) | ||

| Hepatorenal syndrome | 3 (5.4) | 16 (11.6) | 19 (9.8) | ||

| ACLF | 2 (3.6) | 23 (16.7) | 25 (12.9) | ||

| Child-Pugh | A | 8 (13.3)* | 25 (17.7) | 33 (16.4) | 0.606 (0.739) |

| B | 30 (50.0) | 68 (48.2) | 98 (48.8) | ||

| C | 22 36.7) | 48 (34.0) | 70 (34.8) | ||

| Hepatocarcinoma | Yes | 61.7 % | 26.2 % | 36.8 % | 22.707 (0.000) |

| No | 38.3 % | 73.8 % | 63.2 % | ||

| Hospital with transplant unit | Yes | 56.7 % | 77.3 % | 71.1 % | 8.733 (0.003) |

| No | 43.3 % | 22.7 % | 28.9 % | ||

| Location of death | Ward | 60 (100.0) | 96 (68.1) | 156 (77.6) | 26.673 (0.000) |

| ICU | 0 (0.0) | 45 (31.6) | 45 (22.4) | ||

χ (p) – Chi-square independence test statistic (significance level)

Analysis of age at death, Charlson index, length of illness, MELD-Na index, number of decompensations, emergencies, or hospitalizations when referring to palliative care.

X¯ ± s – mean ± standard deviation; T (p) – Parametric test statistics (level of significance) for comparing results between patients considered for palliative care and those who were not.

Overall, the main cause of ESLD is alcohol (60.2 %; n = 121), followed by hepatitis C virus infection (22.9 %; n = 46). Regarding the type of decompensation, it was observed that overall, the main types were: ascites (21.6 %; n = 42); hepatic encephalopathy (21.1 %; n = 41) and gastrointestinal bleeding (17.5 %; n = 34). The Meld-Na was 19.72 ± 6.02, with a median of 19.00 and almost half had a Child-Pugh class B score (48.8 %; n = 98). On average, patients had been diagnosed with chronic liver disease for 4.01 ± 3.23 years, with a median of 3 years, and the majority of patients (63.2 %; n = 127) did not have hepatocarcinoma.

3.2Evolution of referral to palliative careWere evaluated by palliative care 29.9 % (n = 60) of the patients, with an annual increase in the referral rate from 26.7 % in 2017 to 38.3 % in 2019, the results are presented in Fig. 2. Even though without statistical significance (χ=1.322; p = 0.516).

3.3Factors associated with referral to palliative care (Tables 3 and 4)Patients evaluated by palliative care had a higher average age of 65.72 ± 11.70 vs. 62.10 ± 11.44 years (T = 8.733; p = 0.003) and were significantly female (χ=8.733; p = 0.003), with more women assessed than theoretically expected. It should also be noted that these patients had a higher Charlson index 7.92 ± 2.87 vs. 6.63 ± 2.90 (T = 2.871; p = 0.005) and a lower Karnofsky functionality scale (χ = 18.104; p = 0.000).

The majority of patients not assessed by palliative care (66.0 %; n = 93) had alcohol as the cause of ESLD (χ = 6.537; p = 0.012). The type of decompensation was significantly associated with palliative care assessment (χ = 17.649; p = 0.007), highlighting the high number of cases of ascites and hepatic encephalopathy in these patients. The presence of hepatocarcinoma was also significantly associated with the evaluation for palliative care (χ = 22.707; p = 0.000). No patient who died in the intensive care unit was referred to palliative care assessment (χ = 26.673; p = 0.000).

On average, MELD-Na values are identical between patients assessed by palliative care and those who were not: 19.28 ± 6.60 vs. 19.90 ± 5.78 (T = -0.664; p = 0.507). Also, the severity of the disease according to the Child-Pugh score was not significantly associated with the assessment for palliative care (χ = 0.606; p = 0.739). The number of decompensations, number of emergency visits and number of hospitalizations presented, on average, higher results in patients assessed by palliative care, but without statistically significant differences.

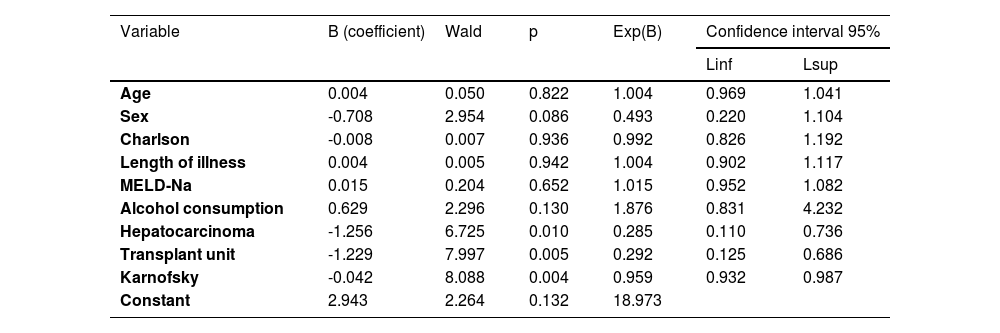

3.4Multivariate analysisTo assess the significance of age, sex, Charlson index, disease duration, MELD-Na, alcohol consumption, presence of hepatocarcinoma and Karnofsky index on the probability of referral to palliative care, logistic regression was used using the enter method (Table 5). The sensitivity of the model is 89.4 % and the specificity is 48.3 %, revealing that the presence of hepatocarcinoma (b_HCC=-1.256; X_Wald^2=6.725; p = 0.010) and the Karnofsky index (b_Karnosfsky = -0.042; X_Wald^2 = 8.088; p = 0.004) have a statistically significant effect on the logit of the probability of referral to palliative care. The absence of hepatocarcinoma reduces the probability of referral to palliative care by 71.5 % vs. 28.5 %. It is also clear that for each increase of one unit in the Karnofsky index, the probability of referral to palliative care decreases by 4.1 %.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with palliative care referral.

The time between assessment for palliative care and the patient's death varied between a minimum of 1 day and a maximum of 196 days, with a median of 6.5 days. However, patients with hepatocarcinoma had, on average, a time between referral to palliative care and death, 30.11 ± 43.77 days, longer than patients without hepatocarcinoma, 9.09 ± 13.28 days (T = 2.726; p = 0.009). In fact, 50 % of patients with hepatocarcinoma died within 12 days of referral, and patients without hepatocarcinoma died within four days of referral.

4DiscussionOur study shows that palliative care intervention differs based on factors such as the presence of hepatocarcinoma or the patient's functional state. We further confirm a major increase in the rate of referral to palliative care, which, however, continues to occur late. With the majority of studies using this methodology focusing on the United States [21,22], this is one of the few European studies of its kind [23,24] and the first in the country to use a multicenter strategy.

This study describes a population with similar characteristics to other studies, showing the weight of alcohol consumption in chronic liver disease [23,30], as well as of hepatitis C virus infection. The low number of cases of chronic liver disease caused by metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease is highlighted in comparison to other studies [23,30]. It is known that the etiologies of cirrhosis are changing over time and differ by region in the world, so in the near future, we believe we can see an increase in our population of chronic liver disease caused by metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease.

This study confirms that palliative care intervention in ESLD varies according to the characteristics of the patient, the disease, and its complications. It also suggests that referral to palliative care is associated with being older and being female. However, in some studies, advanced age appears to be associated with referral to palliative care [21,31], this finding is not unanimous, with studies failing to prove the influence on referral [30] or to show this relationship in the presence of younger individuals [32].

The results were also able to demonstrate that the existence of comorbidities or low functionality also seems to be related to greater referral to palliative care. In logistic regression, a statistically significant effect was documented on the probability of referral to palliative care, with a reduction in the referral rate with an improvement in the patient's functionality. In fact, there have been publications in the literature suggesting the relevance of the Karnofsky Performance Scale in the mortality of patients with ESLD [27,33].

Similar to another study, the presence of liver disease caused by alcohol was associated with non-referral for palliative care [30]. But we have to remember that not only these patients, but also their caregivers present high rates of clinical depression and burden [34]. The types of decompensation, namely ascites and hepatic encephalopathy, were also associated with greater referral to palliative care. These findings have also been demonstrated in other studies, both for ascites [21,31], and for hepatic encephalopathy [32]. We believe that the symptomatic and functional impact that these complications have on the patient may favor the need to discuss a care plan and thus unlock referral to palliative care.

It is also confirmed what appears to be the most consensual data in many studies. The association between the presence of hepatocarcinoma and palliative care assessment generally induces a high referral rate [20,30]. In the logistic regression model presented, the absence of hepatocarcinoma reduces the probability of referral to palliative care by 71.5 %. We also verify the reduced implementation of palliative care in patients admitted to the intensive care unit [32,35]. In our study, 0 patients were referred to palliative care. There are studies showing the apparent influence of Child-Pugh and Meld-Na on referral to palliative care [31]. However, similar to another study [30], this finding was not observed in the sample examined.

This study shows an increasing prevalence in referral to palliative care when compared to initial studies [6,21,31,36]. There is an average percentage of 29.9 %, close to a study carried out in recent years [22]. The referral rate in 2019 (38.3 %) is already close to values published in recent studies [32,37]. It must be acknowledged that, being an analysis of deceased patients, there may be a greater referral to palliative care compared to patients who remained alive and that there are methodological differences between the different studies, as well as external factors, such as the hospital culture and the existence of structured hepatology and palliative care services, which can influence the rates described in the literature.

However, 50 % of patients in the sample died within 6.5 days after assessment by palliative care. In other words, we continue to have late referrals, as supported by data in other studies [11,21,22]. In fact, in a published questionnaire, 97 % of liver transplant team professionals continued to regard palliative care teams as end-of-life care [14]. There are several studies that show the benefit of palliative care intervention in improving the symptoms of patients with ACLD [18–20], as well as reducing disproportionate measures [38], reducing healthcare costs [39], and increasing the discussion of advance directives [38]. Being referral too often delayed until patients are approaching death, the psycho-social and therapeutic benefits of palliative care input may not be achievable. Therefore, more than meeting the referral rate, we will have to start working on timely and adequate referrals as representative of the quality of care.

This is one of only a few European studies examining palliative care referral in ESLD and is strengthened by its multicentric nature and considerable sample size. So, it is anticipated that these findings can be used as a baseline for comparison in future studies. There are some limitations, including the retrospective nature of the study. Findings may be limited by the support of clinical documentation, and, being a retrospective study, we were unable to gather information on patient satisfaction, symptom burden, or family's perspective. Finally, the geographic, demographic, and provider practice patterns may limit the generalizability of our findings to other centers.

The implementation of this work is intended to highlight the importance of the topic for the scientific community and reinforce the existing knowledge in the area of palliative care and ESLD, in line with what was suggested by Patel et al. [16] and Fricker et al. [40].

5ConclusionsIn this study, we demonstrate the increasing intervention of palliative care in patients with ESLD, especially taking into account the functional status or the presence of hepatocarcinoma. However, we continue to see late referrals. Future investigations should identify approaches to achieve an early and concurrent care model that incorporates palliative services into ESLD teams in order to improve patient satisfaction, quality of life, and symptom burden of patients with ESLD.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.