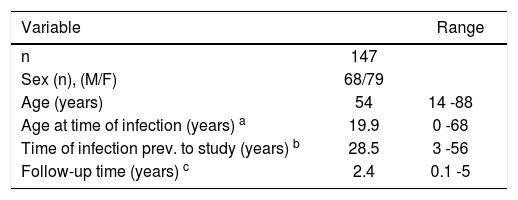

Prevalence, modes of transmission, clinical characteristics and outcomes of hepatitis C (HCV) infection vary in different geographical areas. We aim to describe clinical and epidemiological features of Chilean patients infected with hepatitis C virus. An analysis of demographic, epidemiological, clinical and laboratory data of patients referred to a liver clinic and blood donors with chronic hepatitis C was carried out. 147 patients were evaluated, 68 (46%) were male. Median age was 56 years, median infection age was 27 years and median duration of infection was 27 years. 52.5% of the patients were cirrhotic, and estimated risk of progression to cirrhosis was 16% at 20 years from infection. Risk factors for acquisition of the disease among patients were: Blood transfusion 54%, injection drug use 5%, and risky sexual behavior 2%. No factor was identified in 43% of the patients. Twelve of 64 (18.8%) family members tested positive for HCV antibodies. Genotype 1b was predominant (82%), and 52% of patients had high viral load (>850.000 IU/ mL). Liver biopsy was available in 50 patients, showing advanced fibrosis in 54%. These patients were in average 10 years older and tended to have longer duration of infection. Hepatocellular carcinoma was present at the moment of enrollment in 7 patients and developed in 4 more patients during follow up (2.4 years). In conclusion, the natural history and clinical characteristics of HCV infection in Chilean patients is similar to that described elsewhere. The main risk factor was blood transfusion. A significant proportion of patients had advanced liver disease or hepatocellular carcinoma at time of diagnosis.

Abbreviations used in this article:

HCV: Hepatitis C Virus

BMI: Body Mass Index

AIDS: Aquired immunodeficiency syndrome

RIBA: Recombinant Immuno-Blot Assay

RT-PCR: Reverse transcription - polymerase chain reaction

MCV: Mean Corpuscular Volume

AST: Aspartate aminotransferase

ALT: Alanine aminotransferase

GGTP: Gamma glutamil transpeptidase

AP: Alkaline phosphatase

DM: Diabetes mellitus

CI 95%: Confidence Interval = 95%

IFN: Interferon

ROC: Receiver operator characteristics

IntroductionAccording to the World Health Organization, approximately 170 million people worldwide are infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV),1 being roughly five times more prevalent than HIV infection.2 The most frequent complications -cirrhosis and hepatocarcinoma- are a significant source of morbidity and mortality, with considerable social and economic burden.

Worldwide statistics reveal significant geographical variations in the characteristics of the disease, showing different transmission patterns, prevalence and incidence. Chile has been considered as having a relatively low prevalence of hepatitis C.3,4 However, its prevalence among the general population is unknown and statistical data from death registries is difficult to interpret.5 Prevalence of HCV among selected voluntary blood donors in Chile is approximately 0.3%.6 Morover, HCV infection is present in nearly half of patients with non-alcoholic cirrhosis and hepatocarcinoma in Chile.6

The aim of this study is to decribe the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of a group of Chilean patients infected with HCV.

Patients and methodsPatientsPatients included in the study were referred from both the Gastroenterology Outpatient Clinic and Blood Bank of the Pontifical Catholic University Clinical Hospital, after testing positive for HCV serum antibodies, between June 1996 and May 2001.

Patient evaluationAll patients went through a personal interview and answered a standardized questionnaire for demographic, epidemiological and clinical data. A complete physical examination was performed on all patients, registering anthropometric variables. Available laboratory results (biochemistry, histology and radiology) were registered for each patient. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the following formula: BMI = Weight (kg)/[Height (m)]2. Diagnosis of hepatocarcinoma was established by diagnostic liver biopsy and/or at least two compatible imaging studies, associated or not to elevated serum levels of alpha fetoprotein.7 To estimate the age of the patient at the time of infection, the first use of intravenous drugs or the moment of transfusion (when before 1996) was considered. Most interviews were carried out by the same researcher (AS). Patients were followed up every 6 months after inclusion.

Inclusion criteriaPatients with positive serum antibodies for HCV confirmed by RIBA II or with viral RNA detected in serum by reverse-transcription polimerase chain reaction (RTPCR) were included. Patients with positive HCV antibodies and negative HCV RNA by PCR before antiviral treatment were excluded from the study.

Laboratory testsAnti-HCV antibodies were detected by third generation ELISA using Abbott HCV EIA 3.0 detection kit (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, Ill). RT-PCR was performed using an in-house technique up to 1998, and from then on by using the Roche RT-PCR kit in the Molecular Biology Laboratory of our Clinical Hospital. Viral load was determined using Roche Amplicor Cobas 2.0. Viral genotype was determined by analysis of restriction fragment polymorphism after amplification by RT-PCR. Liver biopsy was performed as clinically indicated and inflammatory activity and fibrosis stage were recorded using a validated classification system.8

Registry and analysisThe data was registered in pre-designed charts and analyzed using data-management software (Excel® 2000 and Acces® 2000, Microsoft® Inc.). Statistical analysis was performed with the assistance of InStat® 3.0 (Graph-Pad Software® Inc.). Continuous and categorical variables were compared using Student's T test and 2-tail Fisher's test, respectively, considering a significant p value <0.05. Confidence intervals for proportions were calculated using the Wald method.

ResultsDemographic features, epidemiology and clinical characteristics

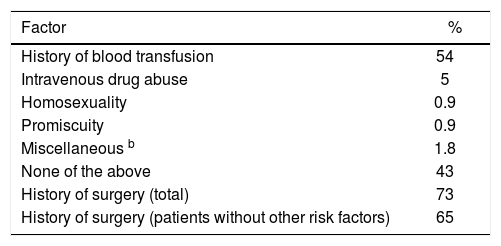

Demographic characteristics and identified risk factors for acquiring the disease are summarized in tables IandII, respectively.

Patients without history of transfusion or intravenous drug abuse had the following risk factors: Risky sexual behavior 1/47 (2.1%) and surgery 31/47 (66%). There were no cases in which a history of tattooing was identified as a possible means of infection with HCV.

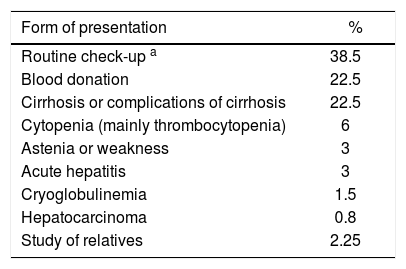

The initial presentation of the disease which led eventually to diagnosis of HCV infection is detailed in table III. Remarkably, a large group of patients had no symptoms directly related to liver disease at the time of diagnosis.

Form of presentation among 147 patients diagnosed with chronic hepatitis C in Chile.

| Form of presentation | % |

|---|---|

| Routine check-up a | 38.5 |

| Blood donation | 22.5 |

| Cirrhosis or complications of cirrhosis | 22.5 |

| Cytopenia (mainly thrombocytopenia) | 6 |

| Astenia or weakness | 3 |

| Acute hepatitis | 3 |

| Cryoglobulinemia | 1.5 |

| Hepatocarcinoma | 0.8 |

| Study of relatives | 2.25 |

Anti-HCV antibodies were positive in 12 of 64 direct relatives (sexual partner, children or siblings), with a prevalence of 18.8% in family members.

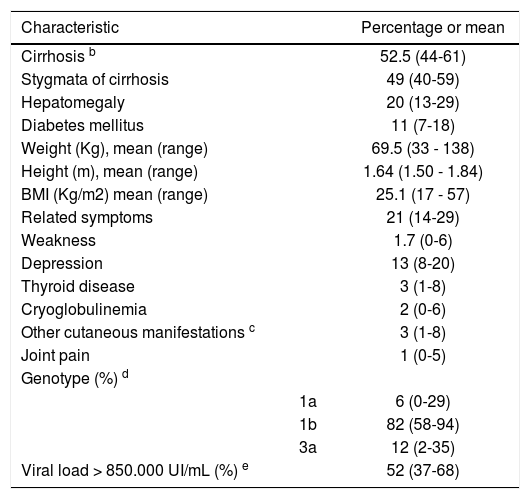

Clinical characteristics of patients are summarized in table IV. Most patients had evidence of advanced liver disease or cirrhosis (52.5%) and genotype 1b was predominant.

Clinical characteristicsa.

| Characteristic | Percentage or mean | |

|---|---|---|

| Cirrhosis b | 52.5 (44-61) | |

| Stygmata of cirrhosis | 49 (40-59) | |

| Hepatomegaly | 20 (13-29) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 (7-18) | |

| Weight (Kg), mean (range) | 69.5 (33 - 138) | |

| Height (m), mean (range) | 1.64 (1.50 - 1.84) | |

| BMI (Kg/m2) mean (range) | 25.1 (17 - 57) | |

| Related symptoms | 21 (14-29) | |

| Weakness | 1.7 (0-6) | |

| Depression | 13 (8-20) | |

| Thyroid disease | 3 (1-8) | |

| Cryoglobulinemia | 2 (0-6) | |

| Other cutaneous manifestations c | 3 (1-8) | |

| Joint pain | 1 (0-5) | |

| Genotype (%) d | ||

| 1a | 6 (0-29) | |

| 1b | 82 (58-94) | |

| 3a | 12 (2-35) | |

| Viral load > 850.000 UI/mL (%) e | 52 (37-68) |

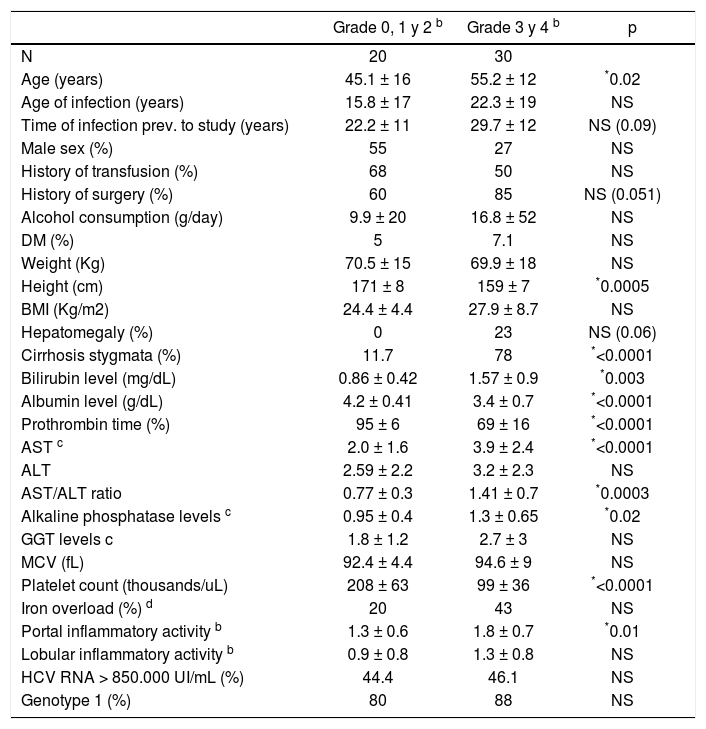

A liver biopsy was performed in 56 of the 147 patients (38%), and information was available for analysis in 50 (Table V). Liver biopsy results showed that 53.6% of the patients had advanced fibrosis (stage 3 or 4). Cirrhosis (stage 4 fibrosis) accounted for 38% of patients with liver biopsy. The median portal inflammatory score was 1.5 and for lobular inflammatory activity was 1. Median fibrosis score was 3. Only 23% of the patients with grade 3 or 4 fibrosis showed hepatomegaly at physical examination, many of which had no clinical stigmata suggestive of chronic liver disease (22%). A platelet count of less than 140.000 had a sensitivity of 88.8% for predicting grade 3 or 4 fibrosis. Meanwhile, a platelet count under 118.000 was 100% specific for this condition. An AST/ ALT ratio higher than 1 had a positive predictive value of 83% for advanced fibrosis.

Factors related to severity of fibrosis in 50 patients who underwent liver biopsya.

| Grade 0, 1 y 2 b | Grade 3 y 4 b | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 20 | 30 | |

| Age (years) | 45.1 ± 16 | 55.2 ± 12 | *0.02 |

| Age of infection (years) | 15.8 ± 17 | 22.3 ± 19 | NS |

| Time of infection prev. to study (years) | 22.2 ± 11 | 29.7 ± 12 | NS (0.09) |

| Male sex (%) | 55 | 27 | NS |

| History of transfusion (%) | 68 | 50 | NS |

| History of surgery (%) | 60 | 85 | NS (0.051) |

| Alcohol consumption (g/day) | 9.9 ± 20 | 16.8 ± 52 | NS |

| DM (%) | 5 | 7.1 | NS |

| Weight (Kg) | 70.5 ± 15 | 69.9 ± 18 | NS |

| Height (cm) | 171 ± 8 | 159 ± 7 | *0.0005 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 24.4 ± 4.4 | 27.9 ± 8.7 | NS |

| Hepatomegaly (%) | 0 | 23 | NS (0.06) |

| Cirrhosis stygmata (%) | 11.7 | 78 | *<0.0001 |

| Bilirubin level (mg/dL) | 0.86 ± 0.42 | 1.57 ± 0.9 | *0.003 |

| Albumin level (g/dL) | 4.2 ± 0.41 | 3.4 ± 0.7 | *<0.0001 |

| Prothrombin time (%) | 95 ± 6 | 69 ± 16 | *<0.0001 |

| AST c | 2.0 ± 1.6 | 3.9 ± 2.4 | *<0.0001 |

| ALT | 2.59 ± 2.2 | 3.2 ± 2.3 | NS |

| AST/ALT ratio | 0.77 ± 0.3 | 1.41 ± 0.7 | *0.0003 |

| Alkaline phosphatase levels c | 0.95 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.65 | *0.02 |

| GGT levels c | 1.8 ± 1.2 | 2.7 ± 3 | NS |

| MCV (fL) | 92.4 ± 4.4 | 94.6 ± 9 | NS |

| Platelet count (thousands/uL) | 208 ± 63 | 99 ± 36 | *<0.0001 |

| Iron overload (%) d | 20 | 43 | NS |

| Portal inflammatory activity b | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | *0.01 |

| Lobular inflammatory activity b | 0.9 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.8 | NS |

| HCV RNA > 850.000 UI/mL (%) | 44.4 | 46.1 | NS |

| Genotype 1 (%) | 80 | 88 | NS |

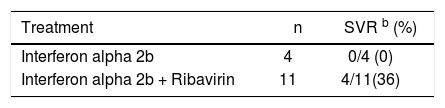

Most patients with clinical indication for treatment did not receive, since it is not covered by the public health system in Chile. Of all patients, only 13 (8.8%) received specific antiviral therapy. Four patients received alphainterpheron as their only treatment, none of them having a sustained response defined as a negative PCR 6 months after completion of treatment. Two of these patients were re-treated with alpha interpheron plus ribavirin. Of these, 1 patient had negative PCR on completion of treatment, but with a positive follow-up PCR 6 months later. Eleven patients received combination treatment for 6 to 12 months, with sustained viral response in 4, (36%, CI 95%: 15-65%). A summary of treatment outcomes is presented in table VI. All 4 had genotype 1b. The following adverse secondary effects were seen in treated patients: Hypothyroidism (3 patients), hyperthyroidism (1 patient), depression that required pharmacological therapy (6 patients) and significant hemolytic anemia (1 patient).

HepatocarcinomaEleven patients developed hepatocarcinoma (7.5%). All of them had established cirrosis. Seven presented initially with hepatocarcinoma and in four patients the diagnosis was made during follow up, which translates to a cumulative of 5.7% in the 70 cirrhotic patients at risk in the follow up period.

Mortality and transplantationTwelve patients died during follow up (8.2%). All of them had cirrhosis and in 50% the cause of death was hepatocarcinoma. Two patients died due to infection, 1 due to complications following liver transplantation, and three due to progressive liver failure. Three subjects received orthotopic liver transplantation during the follow up period due to progressive liver failure.

DiscussionIn Chile, hepatitis C prevalence has been described in selected groups of patients,6,9-12 and its clinical characteristics have been analyzed in a report.13 Our descriptive work presents important additional information about the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of HCV infection in our country, in addition to treatment outcomes and its main consequences: cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.

In our group of patients we identified a history of transfusion of blood or blood derived products as the main risk factor for acquiring the infection. It is notable, nevertheless, that in a significant number of patients there was no identifiable risk factor. We hypothesize that infection in this group of subjects was largely secondary to medical procedures, including reuse of vaccination needles and other practices commonly performed decades ago.

Eventhough genotype was available only in 17 patients; there is a notorious predominance of genotype 1b. Also, a large number of patients carry a high viral load. This supports previous data for genotype distribution in Chilean patients.6,14

We found a high prevalence of positive serum markers (18.8%) in direct relatives of the studied patients. However, we can not consider this as evidence of sexual or household transmission for two reasons: In first place because these are only potential means of transmission and other risk factors cannot be ruled out, and in second place bebecauseof a possible bias due to a higher motivation to return to follow-up in relatives that had a positive antibody.

Age, male sex and alcohol consumption are factors frequently associated to an accelerated progression of fibrosis in hepatitis C infection.15,16 In our study the average age was 10 years higher in patients with advanced fibrosis; however, neither male sex nor alcohol consumption was significantly associated with more advanced stages of fibrosis. Other factors associated to fibrosis were higher AST levels and inflammatory activity in biopsies. It may be argued that higher AST levels indicate occult alcohol consumption; but there was no correlation of fibrosis with GGTP and MCV values, other variables usually considered markers of alcohol abuse. Platelet count and AST/ALT ratio showed a good predictive value for fibrosis when analyzed using ROC curves in our group of patients. However, its real value as a predictor of fibrosis depends on the prevalence of fibrosis in the studied group (pre-test probability value), thus having uncertain usefulness in unselected population.

We observed considerable morbidity and mortality associated to hepatitis C virus infection during the short follow-up period, including hepatocarcinoma (4.4% incidence) and death or need for ortotopic liver transplantation (10%). In a previous retrospective study of 32 Chilean patients there were 3 cases of death due to liver failure, but no report of hepatocarcinoma.13 Our study was not intended specifically to measure prospectively mortality or incidence of hepatocarcinoma. We belive that the relatively high incidence of hepatocarcinoma can be explained by a methodological bias, since our institution is a referral center for hepatocarcinoma (referral bias) and we started regular screening for hepatocarcinoma with alfa fetoprotein and abdominal ultrasound in all these patients (detection bias).

There are conflicting reports in the literature regarding the natural history of this disease, probably due to inclusion bias, with worst results found in studies performed in reference centers,17,18 and findings suggesting a more benign course in retrospective-concurrent studies.19-22 We believe our study comes closer to the first group, despite the effort to balance our studied group with patients diagnosed in a blood bank, who are usually described as having a more benign course of their disease.23,24 By means of the method described by Freeman et al24 for comparing fibrosis progression in different studies, we were able to estimate in 16% the risk of developing cirrhosis during a period of 20 years in our series.

Treatment of hepatitis C has shown considerable improvement in the past years. However, we are still a long way from having a highly effective, low-cost and safe therapy. In our study we describe treatment response in a small group of patients, obtaining similar results to those described worldwide with similar interventions.23,25 In Chile there is currently very limited access to treatment for a disease that cause significant morbidity and mortality, since the diagnostic tests and drugs for treatment are not covered by neither the public nor the private health systems. This led us to ponder on the necessity to design public health policies that confront this problem globally (prevention and detection) and grant greater treatment coverage for patients who need it.

In conclusion, data presented in this article allows us a better understanding of the clinical features of HCV infection in Chile and confirms that the natural history, general clinical presentation and response to treatment in South America are similar to elsewhere.