Introduction and aim. Adherence to hepatitis C (HCV) care was suboptimal in the interferon era among underserved African Americans (AA), but adherence data in the era of direct acting antivirals (DAA) is lacking in this population. We aimed to evaluate the impact of DAA on HCV care in underserved AA.

Material and methods. Clinical records of AAs undergoing HCV evaluation attending a safety net health system liver clinic were reviewed from 2006 to 2011 (pre-DAA), and January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2016 (post-DAA).

Results. 291 patients were identified (129 pre-DAA, and 162 post-DAA). Median age was 58, 66% were male, 91% had HCV genotype 1, and 70% had fibrosis ≥ stage 2. Post-DAA patients were older (60 vs. 53 years; p < 0.001), had higher rates of insurance (98% vs. 88%; p < 0.001), liver fibrosis ≥ stage 2 (77% vs. 61%; p = 0.048), ≥ 2 medical comorbidities (19 vs. 0.8%; p < 0.001), and median baseline log10 HCV RNA (6.07 vs. 5.81 IU/mL; p < 0.001), but lower median ALT (46 vs. 62 U/L; p < 0.001). Post-DAA, fewer patients were treatment ineligible (5.6% vs. 39%; p < 0.001) and more initiated therapy (71% vs. 8.5%; < 0.001), were adherent to HCV care (82% vs. 38%; p < 0.001), and achieved cure (95.7% vs. 63.6%, p < 0.001). Availability of DAA was independently associated with improved adherence to HCV care (OR 10.3, 95% CI 4.84-22.0).

Conclusion. Availability of DAA is associated with increased treatment eligibility, initiation, adherence to HCV care, and cure in HCV-infected underserved AAs; highlighting the critical role of access to DAA in this population.

African Americans (AA) make up 25% of the hepatitis C (HCV)-infected population in the United States and have higher rates of HCV infection than Caucasians.1 In addition, self-identification as non-Hispanic black is an independent predictor of a positive HCV viral load.1 These rates are likely underestimated as HCV prevalence studies often exclude vulnerable populations who are not only disproportionately affected by HCV, but are also at high risk of experiencing health disparities associated with this infection.1–4 Prior to the introduction of direct acting antiviral (DAA) agents, HCV-in-fected underserved AA patients had high rates of treatment ineligibility due to comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions as well as substance abuse.5 Additional barriers to HCV therapy in the interferon-based era included lower treatment response rates that were independent of disease characteristics, baseline viral load, or other viral and patient characteristics,6–8 as well as higher rates of adverse effects related to these therapies. The introduction of interferon sparing, well-tolerated, and highly effective DAA regimens in recent years along with enhanced birth cohort and risk-based screening recommendations provides an unprecedented opportunity to identify HCV-infected patients newly eligible for therapy.9 However, there is no data on adherence to HCV care and treatment uptake in the underserved African American population despite the enactment of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), expanding health insurance coverage.10 We therefore aimed to evaluate the impact of the introduction of second generation DAA-based treatment regimens on HCV treatment eligibility, treatment initiation, and adherence to HCV care among an under-served HCV-infected African American population.

Material and MethodsPatient population and study designThis is a retrospective review of the electronic medical records of patients who were evaluated for HCV treatment at the Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital (ZSFG) liver specialty clinic between January 1, 2006 and June 30, 2011, the time period prior to the introduction of direct acting antiviral HCV medications (pre-DAA era), and between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2016, the time period following approval of second generation DAA (post-DAA era). Patients were referred to the liver specialty clinic from primary care clinics within the San Francisco Health Network (SFHN), which is the traditionally designated safety-net healthcare system in San Francisco, and provides services to over 150,000 patients annually including most of the county’s uninsured and underinsured population.11 The SFHN is administered by the San Francisco Department of Public Health and includes a network of 15 primary care clinics, San Francisco General Hospital (an academic medical center that serves as an acute care and referral facility), and the San Francisco Community Clinic Consortium, which includes 11 federally qualified health centers.11 This study was approved by the University of California San Francisco Committee on Human Research.

All adult patients (18 years and older) who self-identified as African American with chronic HCV (evidence of HCV antibody positivity ≥ 6 months and detectable HCV viral load), who had completed at least one liver specialty clinic visit for evaluation of HCV treatment eligibility during the specified study time period were included in the study. During the entire study period, the liver specialty clinic instituted a formal HCV education class to enhance patient knowledge of HCV disease and treatment, and to improve adherence to HCV care.11,12

Data extractionData was extracted from the electronic medical record with respect to demographics and clinical, laboratory, and imaging studies. Detailed HCV virologic characteristics including viral load, genotype, co-infection with hepatitis B (HBV) or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), HCV treatment regimen, and treatment response were captured. Severity of liver disease was determined either by non-invasive Fibrosure test,13 liver biopsy if available, or abdominal imaging studies documenting the presence of cirrhosis. History of decompensated liver disease was determined by standard biochemical or clinical parameters (such as ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and variceal hemorrhage).

Treatment eligibility status (treatment eligible, treatment ineligible, or undergoing eligibility evaluation) and reasons for ineligibility were determined from the last attended liver clinic provider note. Patients were deemed adherent to HCV care if they returned to subsequent clinic visits after being deemed treatment eligible or while undergoing evaluation for treatment eligibility. Patients who were deemed ineligible for treatment were not included in the adherence data analysis.

HCV treatmentAll subjects pre-DAA received standard of care pegylated interferon and ribavirin combination therapy. Second generation DAAs (post-DAA) included sofosbuvir, simeprevir, ledipasvir, daclatasvir, paritaprevir/ritonavir/ ombitasvir/dasabuvir, elbasvir/ grazoprevir, and velpatasvir. The standard of care planned duration of therapy for each combination regimen was used.14 Treatment success was determined by standard sustained virologic response (SVR) documentation as undetectable HCV viral load at 24 weeks following end of therapy for the pre-DAA era and as undetectable HCV viral load at 12 weeks following end of therapy for the post-DAA era.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics were generated using median (interquartile range) for continuous variables, and frequency (%) for qualitative variables. Patient characteristics were compared between pre- and post-DAA using the Chisquare (χ2) test (Fisher’s exact test when appropriate) for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables. Similarly, patient characteristics were compared between those lost to follow up versus not lost to follow up using χ2 (Fisher’s exact when appropriate) for categorical and Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables. The difference in the proportion of categorical variables among those who were or were not adherent to HCV care was further assessed using the Z-test. Univariate analysis was used to evaluate the factors associated with receipt of therapy and adherence to HCV care. Factors associated with receipt of therapy and adherence to clinic visits were then assessed using multivariate stepwise forward selection logistic regression modeling from an a priori compiled list and adjusted for age, sex, and insurance status. Statistical significance was assessed at a p-value of < 0.05 (2-sided). All analyses were performed using Stata version 13 statistical software, Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX.

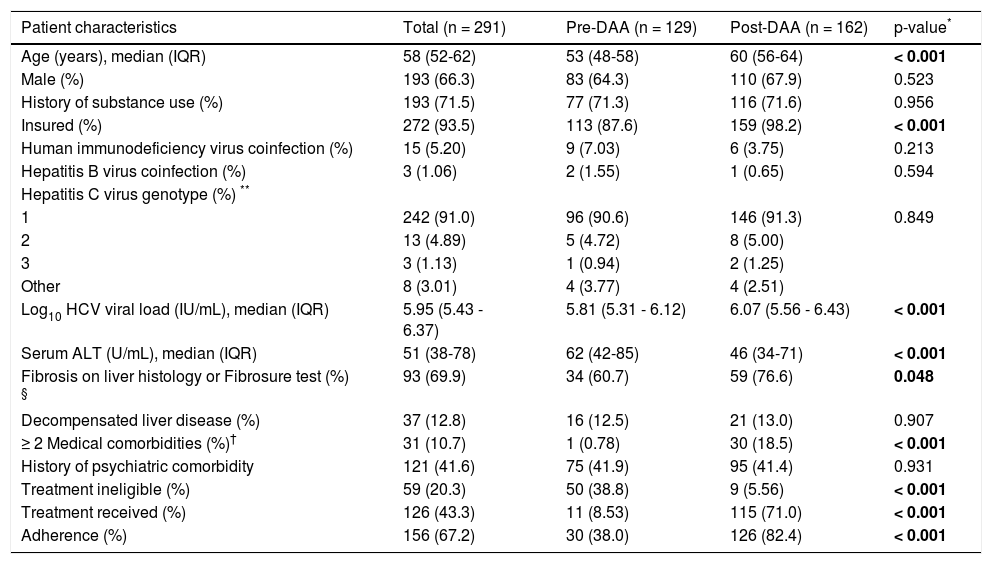

ResultsPatient characteristicsA total of 291 African American patients were identified during the study period, of whom 129 were pre-DAA and 162 were post-DAA. Table 1 summarizes patient characteristics overall, and by pre- and post-DAA. Overall, the median age was 58 years (52-62), 66% were male, and 91% had HCV genotype 1. Thirty-two percent of patients had a liver biopsy, and an additional 16% had Fibrosure test results available; about 70% of these patients had liver fibrosis stage ≥ 2. Compared to pre-DAA patients, patients in the post-DAA group were older (60 vs. 53 years; p < 0.001), more likely to be insured (98% vs. 88%; p < 0.001), had higher median baseline log10 HCV viral loads (6.07 IU/mL vs. 5.81 IU/mL; p < 0.001), had lower median alanine transaminase (ALT) levels (46 U/L vs. 62 U/L; p < 0.001), were more likely to have liver fibrosis > stage 2 (77% vs. 61%; p = 0.048), and were more likely to have ≥ 2 medical comorbidities (19% vs. 0.8%; p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in rates of illicit drug use or psychiatric comorbidity. A similar proportion (~13%) of patients pre- and post-DAA had evidence of decompensated liver disease.

Baseline patient characteristics.

| Patient characteristics | Total (n = 291) | Pre-DAA (n = 129) | Post-DAA (n = 162) | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 58 (52-62) | 53 (48-58) | 60 (56-64) | < 0.001 |

| Male (%) | 193 (66.3) | 83 (64.3) | 110 (67.9) | 0.523 |

| History of substance use (%) | 193 (71.5) | 77 (71.3) | 116 (71.6) | 0.956 |

| Insured (%) | 272 (93.5) | 113 (87.6) | 159 (98.2) | < 0.001 |

| Human immunodeficiency virus coinfection (%) | 15 (5.20) | 9 (7.03) | 6 (3.75) | 0.213 |

| Hepatitis B virus coinfection (%) | 3 (1.06) | 2 (1.55) | 1 (0.65) | 0.594 |

| Hepatitis C virus genotype (%) ** | ||||

| 1 | 242 (91.0) | 96 (90.6) | 146 (91.3) | 0.849 |

| 2 | 13 (4.89) | 5 (4.72) | 8 (5.00) | |

| 3 | 3 (1.13) | 1 (0.94) | 2 (1.25) | |

| Other | 8 (3.01) | 4 (3.77) | 4 (2.51) | |

| Log10 HCV viral load (IU/mL), median (IQR) | 5.95 (5.43 - 6.37) | 5.81 (5.31 - 6.12) | 6.07 (5.56 - 6.43) | < 0.001 |

| Serum ALT (U/mL), median (IQR) | 51 (38-78) | 62 (42-85) | 46 (34-71) | < 0.001 |

| Fibrosis on liver histology or Fibrosure test (%) § | 93 (69.9) | 34 (60.7) | 59 (76.6) | 0.048 |

| Decompensated liver disease (%) | 37 (12.8) | 16 (12.5) | 21 (13.0) | 0.907 |

| ≥ 2 Medical comorbidities (%)† | 31 (10.7) | 1 (0.78) | 30 (18.5) | < 0.001 |

| History of psychiatric comorbidity | 121 (41.6) | 75 (41.9) | 95 (41.4) | 0.931 |

| Treatment ineligible (%) | 59 (20.3) | 50 (38.8) | 9 (5.56) | < 0.001 |

| Treatment received (%) | 126 (43.3) | 11 (8.53) | 115 (71.0) | < 0.001 |

| Adherence (%) | 156 (67.2) | 30 (38.0) | 126 (82.4) | < 0.001 |

IQR: interquartile range. ALT: alanine aminotransferase.

In the post-DAA era, fewer patients were considered ineligible for treatment (5.6% vs. 39%; p < 0.001), more patients received HCV therapy (71% vs. 8.5%; p < 0.001), and more were adherent to HCV care (82% vs. 38%; p < 0.001) (Table 1). Among those 47 patients who did not receive HCV therapy post-DAA, reasons for lack of receipt of HCV therapy included awaiting further work-up (n = 18), awaiting medication approval (n = 13), patient deferment of therapy (n = 8), and provider concern for poor adherence to HCV medications due to ongoing substance use or uncontrolled psychiatric condition (n = 8).

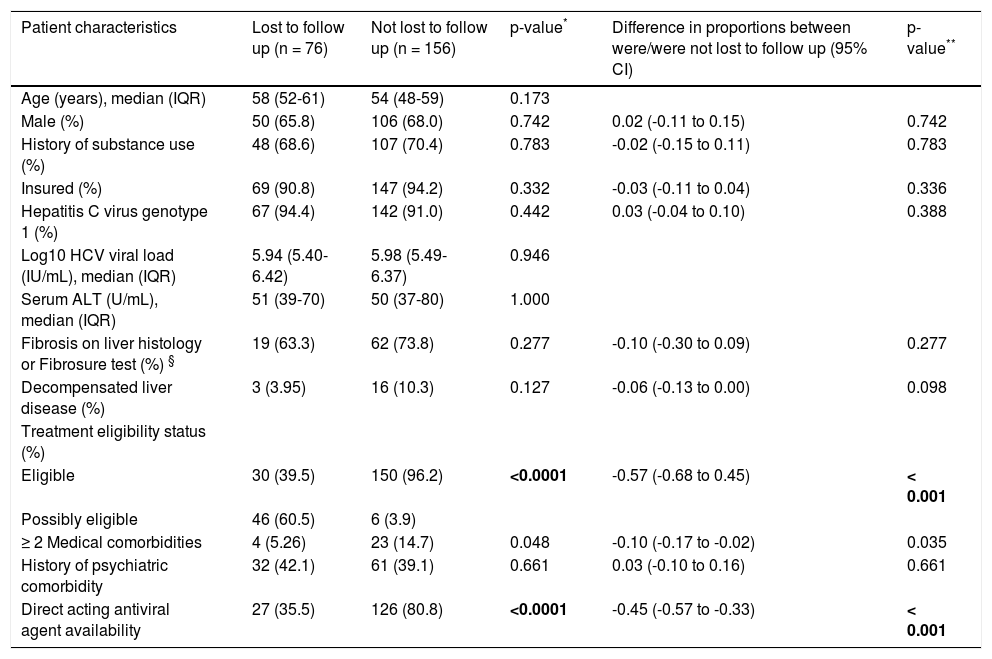

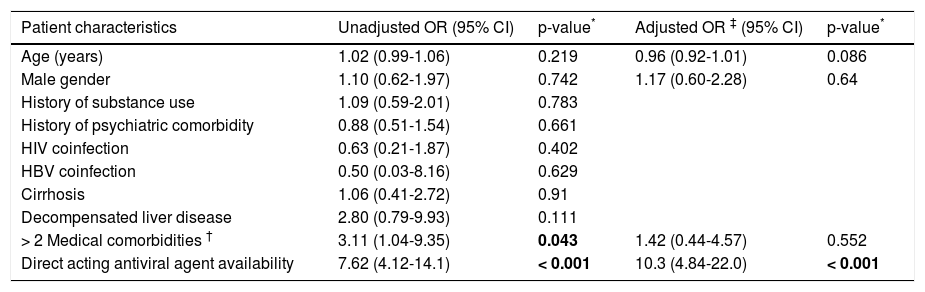

Factors associated with adherence to HCV careOf the 232 patients who were either eligible for therapy or in the process of being evaluated for eligibility, 76 patients were non-adherent to clinic visits [49 (38%) pre-DAA and 27 (20.9%) post-DAA, p < 0.0001)]. Patient characteristics of those who were and were not lost to follow up are listed in table 2. Patients who were lost to follow-up were more likely to be in the process of determining treatment eligibility (category defined as potentially eligible for treatment) (difference of 57%; p < 0.001) and had fewer than two medical comorbidities (difference of 10%; p = 0.035) compared to those who were not lost to follow-up. Lack of access to DAA therapy was also a significant factor (difference of 45%; p < 0.001) contributing to adherence to subsequent clinic visits. On multivariate modeling, only the availability of DAA (post-DAA) remained positively associated with adherence to subsequent clinic visits (OR 10.3, 95% CI 4.84-22.0) after adjusting for age, sex, and insurance status (Table 3).

Characteristics of patients who were and were not lost to follow up among treatment eligible or possibly eligible groups.

| Patient characteristics | Lost to follow up (n = 76) | Not lost to follow up (n = 156) | p-value* | Difference in proportions between were/were not lost to follow up (95% CI) | p-value** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 58 (52-61) | 54 (48-59) | 0.173 | ||

| Male (%) | 50 (65.8) | 106 (68.0) | 0.742 | 0.02 (-0.11 to 0.15) | 0.742 |

| History of substance use (%) | 48 (68.6) | 107 (70.4) | 0.783 | -0.02 (-0.15 to 0.11) | 0.783 |

| Insured (%) | 69 (90.8) | 147 (94.2) | 0.332 | -0.03 (-0.11 to 0.04) | 0.336 |

| Hepatitis C virus genotype 1 (%) | 67 (94.4) | 142 (91.0) | 0.442 | 0.03 (-0.04 to 0.10) | 0.388 |

| Log10 HCV viral load (IU/mL), median (IQR) | 5.94 (5.40-6.42) | 5.98 (5.49-6.37) | 0.946 | ||

| Serum ALT (U/mL), median (IQR) | 51 (39-70) | 50 (37-80) | 1.000 | ||

| Fibrosis on liver histology or Fibrosure test (%) § | 19 (63.3) | 62 (73.8) | 0.277 | -0.10 (-0.30 to 0.09) | 0.277 |

| Decompensated liver disease (%) | 3 (3.95) | 16 (10.3) | 0.127 | -0.06 (-0.13 to 0.00) | 0.098 |

| Treatment eligibility status (%) | |||||

| Eligible | 30 (39.5) | 150 (96.2) | <0.0001 | -0.57 (-0.68 to 0.45) | < 0.001 |

| Possibly eligible | 46 (60.5) | 6 (3.9) | |||

| ≥ 2 Medical comorbidities | 4 (5.26) | 23 (14.7) | 0.048 | -0.10 (-0.17 to -0.02) | 0.035 |

| History of psychiatric comorbidity | 32 (42.1) | 61 (39.1) | 0.661 | 0.03 (-0.10 to 0.16) | 0.661 |

| Direct acting antiviral agent availability | 27 (35.5) | 126 (80.8) | <0.0001 | -0.45 (-0.57 to -0.33) | < 0.001 |

ALT: alanine aminotransferase. IQR: interquartile range.

Factors associated with adherence.

| Patient characteristics | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value* | Adjusted OR ‡ (95% CI) | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1.02 (0.99-1.06) | 0.219 | 0.96 (0.92-1.01) | 0.086 |

| Male gender | 1.10 (0.62-1.97) | 0.742 | 1.17 (0.60-2.28) | 0.64 |

| History of substance use | 1.09 (0.59-2.01) | 0.783 | ||

| History of psychiatric comorbidity | 0.88 (0.51-1.54) | 0.661 | ||

| HIV coinfection | 0.63 (0.21-1.87) | 0.402 | ||

| HBV coinfection | 0.50 (0.03-8.16) | 0.629 | ||

| Cirrhosis | 1.06 (0.41-2.72) | 0.91 | ||

| Decompensated liver disease | 2.80 (0.79-9.93) | 0.111 | ||

| > 2 Medical comorbidities † | 3.11 (1.04-9.35) | 0.043 | 1.42 (0.44-4.57) | 0.552 |

| Direct acting antiviral agent availability | 7.62 (4.12-14.1) | < 0.001 | 10.3 (4.84-22.0) | < 0.001 |

A total of 126 patients (11 pre-DAA and 115 post-DAA) initiated HCV therapy during the study period. In the pre-DAA period, all patients received standard of care pegylated-interferon and ribavirin combined therapy. In the post-DAA period, sofosbuvir/ledipasvir ± ribavirin was the most common treatment regimen used (65%). The frequency of other regimens used were: elbasvir/grazoprevir ± ribavirin (10%), sofosbuvir/simeprevir (7%), sofosbuvir/daclatasvir ± ribavirin (7%), sofosbuvir/pegylated interferon/ribavirin (4%), sofosbuvir/velpatasvir ± ribavirin (4%), and paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir/dasabuvir (3%). In the pre-DAA era, 64% of patients achieved SVR. Among 115 patients in the post-DAA era who initiated therapy, 93 had reached the SVR time point at data analysis and 89 (95.7%) achieved SVR. On univariate analysis, older age (OR 1.07, 95% CI 1.03 - 1.10, p<0.001) and presence of ≥ 2 medical comorbidities (OR 3.1, 95% CI 1.40 - 6.84, p = 0.005) were associated with higher rates of receiving HCV therapy. On multivariate analysis adjusting for gender and insurance status, older age remained positively associated with receipt of HCV treatment (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.03-1.10, p < 0.001) and presence of ≥ 2 medical comorbidities was also associated with higher odds of receiving HCV therapy but this did not reach statistical significance (OR 2.22, 95% CI 0.98-5.04, p = 0.055).

DiscussionThis is the first study to report real world data on the impact of second generation DAA use on HCV treatment eligibility, initiation, and adherence to HCV care in a HCV-infected African American population accessing care in a liver specialty clinic within a safety-net healthcare system. We demonstrate that a significantly higher percentage of underserved AAs were treatment eligible and received treatment in the post-DAA era compared to the pre-DAA era. Conversely, lack of DAA access was significantly associated with subsequent poor adherence to HCV care among this population. These findings were independent of insurance status with the introduction of the ACA expanding access to insurance coverage in the post-DAA era in the safety net population.

We have previously shown that medical comorbidities and active substance abuse were significant reasons for HCV non-treatment in underserved HCV-infected African Americans accessing care within the safety net liver specialty service in the pre-DAA era.5 Consequently, disengaging from HCV care was also highly prevalent.5 While we hypothesized that patient factors may continue to contribute to the observed health disparity in this population, in this study we found that on the contrary, a significantly higher proportion (71% vs. 8.5%) of patients received HCV therapy in the post-DAA era. Additionally, the presence of medical comorbidities and older age were independent predictors and represented priorities for initiation of HCV therapy post-DAA, factors that may have been a relative contraindication to therapy in the interferon-based era. Importantly, access to DAA therapy also impacted adherence to HCV care. DAA availability was associated with a 10 fold increased odds of adherence to subsequent clinic visits.

In this study, we observed a highly successful outcome of HCV therapy post-DAA with SVR rates of over 95% irrespective of the type of DAA regimen, severity of liver disease, and other viral and patient factors among this marginalized population. This high success rate is consistent with prior reports showing 97% SVR within a more racially diverse underserved HCV-population receiving care in the safety-net liver specialty setting15 as well as published clinical trials of various DAA regimens.16,17 However, some studies have also suggested an influence of treatment duration and regimen on SVR rates in African Americans. For example, in a recent study from the Veteran’s Health Administration, black race was associated with lower SVR rates (adjusted OR 0.77) compared to whites.18 Blacks treated with sofosbuvir/ledipasvir for a shorter duration of 8 weeks were less likely to achieve SVR compared to the longer duration of 12 weeks, suggesting a possible impact of treatment duration on treatment response in this population.18 Also, in the ION3 clinical trial, the SVR rates with sofosbuvir/ledipasvir were lower in blacks (83% vs. 92%) if baseline HCV viral load was ≥ 6 × 106 IU/mL and there was no ribavirin used, and there was a higher relapse rate among those treated with 8-week (vs. 12-week) duration of therapy (9% vs. 4%).16 Although high response rates in our study precludes meaningful comparisons of non-responders, we did not observe any differences in treatment regimen and duration among the four patients that did not respond to HCV therapy.

While this is the first study to assess pre- and post-DAA HCV care in the underserved African American population, our study is limited by sample size and evaluation within the liver specialty clinic setting, which may not be generalizable to the non-specialty clinical setting. In addition, it is possible that unmeasured factors may have contributed to improved adherence in the post-DAA era including patient awareness of highly successful newer HCV treatment regimens, significant cost of these medications, and a potentially stronger emphasis on adherence considering the possibility of developing viral resistance19 with these newer agents which did not occur with interferon/ribavirin combination therapy. Nevertheless, we have shown a significant uptake of therapy independent of limited access to these regimens.

In conclusion, despite the known medical and psychosocial challenges faced by underserved AA populations, the availability of DAA-based therapies has significantly improved treatment eligibility, treatment initiation, treatment success, as well as adherence to HCV care compared to pre-DAA era therapies. DAA access appears to be the single most important factor influencing engagement with HCV care among the underserved African American population. Thus, eliminating the barrier of access to DAA regimens will likely significantly reduce hepatitis C disparities, a public health priority, in this underserved population.

Abbreviations- •

AA: African American.

- •

ACA: Affordable Care Act.

- •

ALT: alanine transaminase.

- •

DAA: direct acting antiviral.

- •

HBV: hepatitis B virus.

- •

HCV: hepatitis C virus.

- •

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

- •

SFHN: San Francisco Health Network.

- •

SVR: sustained virologic response.

- •

ZSFG: Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center.

Dr. Khalili has research grant support from Gilead Inc. and Intercept Pharmaceuticals and has participated in the advisory boards of Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead Inc., and Intercept Pharmaceuticals. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health K24AA022523 (to M.K.) and P30 DK026743 (UCSF Liver Center).