Background. Efficacy and safety of Pegylated Interferon alfa (PegIFN)-Ribavirin (RBV) for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C (CHC) in routine clinical practice seems to be comparable with results of randomizedcontrolled trials.

Aims. To evaluate the efficacy, tolerability and safety of CHC treatment with PegIFN + RBV in “real world” patients in Argentina and to analyze factors associated with SVR.

Methods. Medical records of patients treated according to current guidelines from 2001 to 2008 were reviewed.

Results. 235 patients were included and 80.8% completed treatment. Discontinuation occurred in 7.6% due to adverse events (AE), and 1.2% dropped-out treatment. Overall SVR was 60.8%. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that being naive (p 0.031) and low basal viral load (p 0.006) were associated with SVR, whereas F3-F4 (p 0.001) and elevated ALT (p 0.023) were associated with non-response. 80% of planned doses completed was associated with 74% SVR (p <0.001). At least one AE was reported in 93.6% of the patients: neutropenia in 27.6%, thrombocytopenia in 15.3%, anemia in 38.7%, psychiatric symptoms in 63.4%, thyroid dysfunction in 10.2%.

Conclusion. Efficacy, tolerability and safety of treatment of CHC in daily practice in Argentina are similar to those reported in randomized controlled trials.

Chronic hepatitis C is one of the main causes of cirrhosis, end stage liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma and liver transplantation in Argentina and worldwide.1,2 Initially, two randomized controlled trials (RCT), treatment with Interferon alfa plus Ribavirin, obtained a sustained virological response (SVR) of 38-43%.3,4 The standard of care in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C is the combination of Pegylated Interferon alfa (PegIFN) plus Ribavirin (RBV). The pivotal controlled clinical trials (RCTs) performed in reference centers in Europe and North America, used PegIFN aIfa-2a (180 pg/week) plus Ribavirin (1000-1200 mg/day),5 PegIFN alfa-2a (180 μg/week) plus Ribavirin (1000-1200 mg/day)6 and PegIFN alfa-2b (1.5 μg/Kg./week) plus Ribavirin (800 mg/day).7 In these three studies, the SVR was 63%, 56% and 54%; SVR was lower in patients infected with genotype 1: 52%, 41% and 42%, than in those infected with genotypes 2 and 3: 80%, 82%, 80%.5-7

However, these results were obtained from highly selected patients, strictly monitored during treatment, and managed according to rigid rules referred to dosing management. Considering these specific characteristics, the results of these trials may not accurately reflect the outcome of treatment in a widely heterogeneous population treated in the daily clinical practice.8 However, available information from Spain, Italy, United States, Canada and Germany,9-14 demonstrate that results in routine clinical practice are similar to those published in RCTs.

The standard HCV treatment has a limited efficacy, is expensive, and associated with frequent and serious adverse events. These factors result in a reduced applicability and adherence to treatment in daily practice. Therefore, an accurate identification of patients with the best probability of obtaining SVR is required. Several factors related with nonresponse have been identified: genotype 1, high basal viral load (VL), age, advanced fibrosis, and obesity.5,6,15-20

The aims of our study are to evaluate the efficacy, tolerability and safety of CHC treatment with PegIFN + RBV in daily clinical practice in Argentina, and to analyze factors associated with a SVR.

Materials and MethodsWe included 235 patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with PEG-interferon alfa-2a or alfa-2b plus Ribavirin in four centres in Argentina. Each centre included all patients treated since January 2001, who had completed 24 weeks of follow-up before February 2009. Patients older than 18 years; HCV RNA positive, all genotypes, treatment naïve or experienced were included. We excluded patients treated in RCTs, those with decompensated liver disease, HIV and/or HBV coinfection, solid organ transplantation, on hemodialysis or with other associated liver disease. Data was obtained from the medical records, and anonymously entered in a database.

Treatment was indicated and monitored according to national and international guidelines: PegI-FN alfa-2a (180 μg/week) or PegIFN alfa-2b (1.5 μg/kg/week) plus Ribavirin (1,000 mg per day for patients weighing 75 kg or less and 1,200 mg per day for those weighing more than 75 kg) for 48 weeks in patients infected with genotypes 1 or 4, and PegIFN alfa-2a (180 μg/week) or PegIFN alfa-2b (1.5 μg/kg/week) plus Ribavirin (800 mg per day) for 24 weeks in patients infected with genotypes 2 or 3. In some cases doses might be different to those recommended, according to individual medical judgment.

SVR was defined as non-detectable HCV RNA on week 24 after treatment. Patients with detectable serum HCV RNA at end of treatment, those who suspended treatment prematurely, and those infected with genotype 1 who did not achieve an early virologic response (EVR), were considered non responders (NR). EVR was defined as a reduction greater than 2 log from basal viral load, at treatment week 12. Patients with non-detectable HCV RNA at the end of treatment who became HCV RNA positive at week 24 of follow-up were considered relapsers (R).

Management of AEs, including dose modifications or treatment suspension was decided by the treating physicians according to national and international guidelines and to their own clinical judgment.

The following data was obtained from the medical records, and entered to a database: age, gender, body weight, epidemiological factors, ALT, histologic staging (METAVIR), genotype, viral load, dose and duration of treatment, SVR, EVR, adverse events, and dose modifications related to them.

Adverse events were registered as follows: influenza like symptoms (fever, myalgias, headache, etc.), neutropenia (<1,000 cells/mm3), thrombocytopenia (<75,000 cells/mm3), anemia (hemoglobin <10 g/dL), thyroid disorders, and psychiatric disorders (anxiety, insomnia, depression, suicidal ideation).

Statistical analysisMicrosoft Excel 2007® software (Microsoft, Seattle, WA, USA) was used for the database. STATA® statistical software was used for the analysis (version 7.0 Stata Corporation, Tx., USA). Logistic regression test was used to explore base-line factors predicting a sustained virologic response. P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsWe included 235 patients, 135 men (57.4%), median age was 48.2 years (SD 12.5) and median weight was 73.5 kg (SD 13.90). Two hundred and two patients (86.3%) were naïve, 55 (27.7%) had an F3-F4 stage of fibrosis, 139 (59.1%) were infected with genotype 1 and 90 (40.1%) had a low basal viral load (<600,000 IU/mL). Other demographical characteristics are presented in table 1. Comparison of the demographical characteristics from our study with those from RCTs and from other studies performed in daily clinical practice is shown in table 2.

characteristics.

| Variable | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Total | 235 (100) |

| Men | 135 (57.4) |

| Weight > 85 kg | 45 (19.1) |

| Naïve | 203 (86.3) |

| Pretreatment liver biopsy | 195 (82.9) |

| F0-2 | 180 (73.3) |

| F3-4 | 55 (27.7) |

| Cirrhosis | 25 (12.6) |

| Pretreatment elevated ALT | 212 (90.2) |

| Genotype 1 | 139 (59.1) |

| Genotype 2 | 51 (21.7) |

| Genotype 3 | 42 (17.8) |

| Genotype 4 | 3 (1.3) |

| Basal viral load <600.000 lU/mL | 90 (40.1) |

| PEG IFN α2a | 191 (81.2) |

| PEG IFN α2b | 44 (18.7) |

| Transfusions | 49 (20.8) |

| Intravenous drug use | 45 (19.5) |

| Inhalatory drug use | 43 (18.3) |

| Unknown risk factors | 116 (49.3) |

Comparison of demographic characteristics.

| Variable | Our study [n=235] | Borroni, et al.13 [n=436] | Hadziyannis, et al.5 [n=436] | Fried, et al.6 [n=453] | Manns, et al.7[n=511] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | 57 | 58 | 66 | 72 | 63 |

| Age (years) | 48.2±12.5 | 47.7±12.7 | 43± 10.1 | 48.2±10.1 | 43 |

| Weight (kg) | 73.5±14 | 71.1±12 | 77.3±16 | 79.8±17.5 | 82 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 12.6 | 15 | 8 | 12-15 | 5-7 |

| Genotype 1 (%) | 59.1 | 48 | 62 | 65 | 68 |

| Withdrawal (%) | 1.2 | 5 | 1-2 | 1.4 | 1.2 |

All patients received the recommended doses of Peg-IFN alfa. Only 3.6% of the patients infected with genotype 1 received 800 mg of Ribavirin; meanwhile, 27.8% and 8.2% of the patients infected with genotype 2 - 3 received 1,000 mg and 1,200 mg respectively.

One hundred and ninety patients (80.8%) completed treatment, 18 patients (7.6%) stopped treatment due to adverse events and 3 patients (1.2%) abandoned it. 24 patients (10.2%) genotype 1 stopped treatment due to the lack of EVR and were considered non responders.

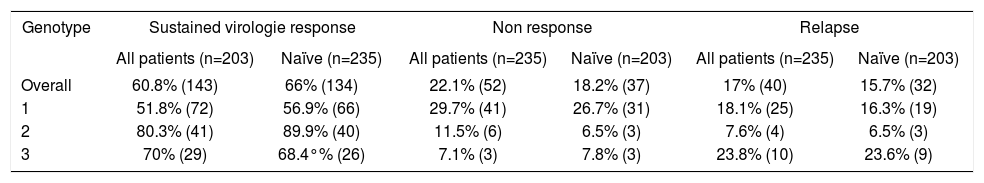

The overall SVR was 60.8% (143 patients), 51.8% (72 patients) in genotype 1, 80.3% (41 patients) in genotype 2; 69% (29 patients) in genotype 3 and 33.3% (1 patient) in genotype 4 (Table 3). The rate of SVR, non response and relapse in naïve and previously treated patients are presented in Table 3. A comparison of SVR rates between our study, randomized clinical trials and other studies of treatment in daily clinical practice is shown in Table 4.

Sustained virologie response, non response and relapse.

| Genotype | Sustained virologie response | Non response | Relapse | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (n=203) | Naïve (n=235) | All patients (n=235) | Naïve (n=203) | All patients (n=235) | Naïve (n=203) | |

| Overall | 60.8% (143) | 66% (134) | 22.1% (52) | 18.2% (37) | 17% (40) | 15.7% (32) |

| 1 | 51.8% (72) | 56.9% (66) | 29.7% (41) | 26.7% (31) | 18.1% (25) | 16.3% (19) |

| 2 | 80.3% (41) | 89.9% (40) | 11.5% (6) | 6.5% (3) | 7.6% (4) | 6.5% (3) |

| 3 | 70% (29) | 68.4°% (26) | 7.1% (3) | 7.8% (3) | 23.8% (10) | 23.6% (9) |

SVR rates obtained from this study, RCTs and other studies evaluating treatment in daily practice.

| Variable | PEG IFN | Overall SVR (%) | SVR G1 (%) | SVR G2-3 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our study all patients [n=235] | α2a/α2b | 61 | 52 | 74 |

| Our study naïve [n=203] | α2a/α2b | 66 | 57 | 77 |

| Hadziyannis, et al.5 [n=436] | α2a | 63 | 52 | 80 |

| Fried, et al.6 [n=453] | α2a | 56 | 46 | 76 |

| Manns, et al.7 [n=511] | α2b | 54 | 42 | 82 |

| Borroni, et al.13 [n=436] | α2a/α2b | 64 | 46 | 84 |

| Thomson, al.11 [n=347] | α2a/α2b | - | 37 | 70 |

| Witthöft, et al.14 [n=309] | α2a | 49 | 40 | 68 |

In the univariate analysis, the absence of previous HCV treatment (OR 4.18) (p <0.001) and a low basal viral load (<600,000 IU/mL) (OR 2.66) (p = 0.001) were associated with a SVR. On the other hand genotype 1 (OR 0.37) (p = 0.001), F3-4 (OR 0.24) (p <0.001), elevated ALT (OR 0.06) (p = 0.007) and weight ≥ 85kg (OR 0.42) (p = 0.011) were associated with non response (Table 5)

Predictors of SVR (univariate analysis).

| Variable | Odds Ratio (OR) | P value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male vs. female) | 0.68 | 0.165 | 0.40-1.16 |

| Age (per year) | 0.99 | 0.371 | 0.96-1.01 |

| Weight ≥85 vs. <85 | 0.42 | 0.011 | 0.42-0.82 |

| Naïve vs. retreatment | 4.18 | <0.001 | 1.87-9.31 |

| Genotype 1 vs. no 1 | 0.37 | 0.001 | 0.21-0.66 |

| F3-4 vs. F0-2 | 0.24 | <0.001 | 0.12-0.46 |

| Basal viral load < vs. ≥600,000 IU/ml | 2.66 | 0.001 | 1.49-4.75 |

| Elevated ALT vs. normal | 0.06 | 0.007 | 0.007-0.45 |

In the multivariate analysis the absence of previous treatment (OR 2.98) (p = 0.031) and a low basal viral load (OR 2.62) (p = 0.006) were associated with a SVR, meanwhile, F3-F4 stages of fibrosis (OR 0.26) (p = 0.001) and elevated ALT (OR 0.08) (p = 0.023) were associated with non response (Table 6).

Predictors of SVR (multivariate analysis).

| Variable | Odds Ratio (OR) | P value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naïve vs. retreatment | 2.98 | 0.031 | 1.10-8.05 |

| Genotype 1 vs. no 1 | 0.62 | 0.194 | 0.30-1.27 |

| F3-4 vs. F0-2 | 0.26 | 0.001 | 0.12-0.56 |

| Basal viral load < vs. ≥600,000 lU/ml | 2.62 | 0.006 | 1.31-5.24 |

| Elevated ALT vs. normal | 0.08 | 0.023 | 0.10-0.71 |

Two hundred and twenty patients (93.6%) reported at least one adverse event: 65 patients (27.6%) developed neutropenia, 36 patients (15.3%) thrombocytopenia, 91 patients (38.7%) anemia, 218 patients (92.7%) reported influenza like symptoms, 24 patients (10.2%) had thyroid disorders, and 149 patients (63.4%) reported psychiatric disorders. In 18 patients (7.6%) treatment was stopped due to severe adverse events: 5 presented neutropenia, 6 thrombocytopenia, 3 suicidal ideation, 1 generalized skin rash, 2 intractable flu like symptoms, and 1 due to anemia.

One hundred and ninety patients (80.8%) accomplished 80% of the treatment, and obtained a SVR of 73.3%. One hundred and eighty four patients (78.3%) received 80% of the planned Peg-IFN doses, and achieved an SVR of 74%; and 176 patients (74.8%) received 80% of RBV doses, and obtained an SVR of 74%. Adherence to treatment was the most important predictor of response: accomplishment of 80% of treatment (OR 27.9, p <0.001, 95% CI 9.52-81.9), 80% of Peg-IFN doses (OR 17.8, p <0.001, 95% CI 7.51-42.2), and 80% of RBV doses (OR 10, p <0.001, 95% CI 4.95-20.16) were significantly associated with SVR. Interruption (OR 0.26, p = 0.031, IC 95%0.079-0.88) or reduction of Peg-IFN doses (OR 0.31, p = 0.001, IC 95% 0.16-0.63), and interruption of RBV doses (OR 0.22, p = 0.031, IC 95% 0.05-0.87) were associated with non-response. Reduction of RBV doses (OR 0.88, p = 0.689, IC 95% 0.42-1.64) did not affect SVR.

DiscussionRandomized controlled trials are considered the “gold standard” to establish the efficacy and safety of drugs. However, these studies are performed in ideal conditions with highly selected patients, trying to minimize the risk of adverse events and to ensure adherence. Otherwise, RCTs are designed to follow strict rules concerning the surveillance and management of adverse events, and establish specific conditions for dose reduction or treatment interruption. These results may be doubtfully extrapolated to daily practice, since both patients and treatment monitoring conditions are usually very different in this scenario. Indeed, the treated population may be widely heterogeneous in demographic characteristics, virological factors and severity of liver disease. Moreover, in daily practice the management of adverse events usually depends on the clinical judgment of the treating physician. These issues are quite relevant in HCV therapy, given the prevalence of the disease and the increasing number of centers involved in the diagnosis and treatment of these patients. Therefore, it becomes necessary to document the results of treatment of CHC in the daily clinical setting.

Although this issue has been analyzed in studies from Europe and North America, data from other regions of the world are scarce. This is the first large study in Argentina and probably in Latin America that evaluates the efficacy and safety of the treatment of chronic hepatitis C in daily practice. The first main finding of our study is that the rate of SVR in our population was similar to that observed in RCTs5-7 and to studies performed in clinical practice in Europe and USA.11,13,14 It is important to emphasize that demographic characteristics are comparable among studies.

Another remarkable finding, was that predictors of SVR were the same than those reported in the literature: non-responders to previous treatment with IFN, genotype 1, basal viral load, weight and severity of fibrosis.5,6,15-20 In the multivariate analysis, genotype 1 was not a predictor of lower rate of SVR, probably due to the number of patients included.

Ethnicity has been considered an important predictor of SVR, as shown by the lower rate of SVR achieved in the African-American population (28% in genotype 1), compared to the Caucasian population.21 It has also been reported a reduced rate of SVR in Spanish speaking Latin-American population from USA and Puerto Rico (34% in genotype 1) compared to Non-Latino Whites.22 These results differ from our findings. Although we did not have a control group, the rate of SVR in our study did not differ from that reported in Caucasian groups. The discrepancy related to the outcome of HCV treatment in Latin-American population may be ascribed to differences in the ethnic origin of Latin-American groups in different countries. Indeed, in our country there is a higher prevalence of European ancestors among the population.22

The main limitation of our study is that the analysis of data was done retrospectively. Therefore, the proportion of patients that did not receive CHC treatment could not be determined. However, the patients were managed by physicians trained in the treatment of CHC. As a consequence, it can be assumed that treatment was indicated or contraindicated according to current guidelines.

Another concern about the results of this study may be related to the optimal dose of CHC treatment. Since recommendations on dosing have changed through the period selected for the analysis (2001 - 2009), some patients could have received suboptimal doses of treatment. However, only 5 patients infected with genotype 1 received lower doses than those currently recommended.

On the other hand, the retrospective analyses reduces the potential bias of changing the routine practice by the fact of being evaluated, as could happen in prospective observational studies (Hawthorne effect).13,23

Another main finding of this study was that the incidence and characteristics of adverse events was not different from previous reports, confirming the safety of CHC treatment.

We also corroborated that adherence to treatment has a main impact in its efficacy. We want to highlight the low rate of withdrawal from treatment in our population (1.2%) (Table 2).

We remark that SVR rate and adherence were similar to those previously reported probably due to the fact that treatments were conducted in referral centers by physicians qualified for the management of patients with CHC.

In conclusion, treatment of chronic hepatitis C with PEG-interferon plus Ribavirin in our country turned out to be similar to those obtained in the clinical practice in Europe and North America and similar to those obtained in randomized clinical trials.

AcknowledgementsWe are indebted to Dr. Hugo Krupitzky for his help with the statistical analysis.