Information about HCV genotypes in infected patients from different regions of Mexico is limited. Objective: To determine the prevalence of HCV genotypes in a group of HCV infected patients who attended a third level Hospital in Northeast of Mexico. Methods: Genotyping analysis was performed using the InnoLiPA-HCV genotype assay in 147 patients (65 males and 82 females, mean age 44 ± 12 years) with positive anti-HCV antibodies and detectable HCV-RNA levels. Results: Infected individuals were more likely to be female (56%). Histological data showed that 63% of the patients had chronic hepatitis, while the remainder presented cirrhosis (37%). The most frequent HCV genotype was 1 (73%). We found the following distribution: genotype 1 (2.7%), 1a (28.6%), 1b (37.4%), 1a/1b (4.1%), 2a (1.4%), 2b (8.8%), 2c (0.7%), 2a/2c (2.7%), 3 (2%), 3a (10.2%), 4 (0.7%) and 4c (0.7%). The most frequent associated risk factor was blood transfusion (72.5%). Conclusion: Prevalence of HCV genotypes in the Northeast of Mexico is similar to those reported previously in other Mexican regions and the most frequent risk factor continues being blood transfusion.

It is estimated that 170 million of people worldwide are infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV).1 In Mexico HCV prevalence for the general population is 1.4%2 but in some risk populations the prevalence is higher.3,4 Although only a small proportion of acute HCV infections are symptomatic, hepatitis C progresses to chronic infection in approximately 60-85% of cases,2,5,6 and 15 to 20% of HCV chronically infected patients develop liver cirrhosis after 20 years, while 1-4% will develop hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).7,8 In the Mexican population chronic liver diseases represent the fourth leading cause of death and the second among productive-aged population.8

HCV is an RNA virus and a member of the Hepacivirus genus classified into the Flaviviridae family. HCV presents high mutation rates and because of that it has been evolved to different genotypes based on nucleotide sequence heterogeneity and classified in six major genotypes and more than 50 subtypes.9 Molecular epidemiologic studies reveal that HCV genotypes coexist in various geographic locations with different prevalence.9 Several reports have shown prevalence of genotypes 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 in Latin America.10-12 In Mexico the predominant genotype is 1 (72.2%), followed by genotype 2 (18%) and 3 (9.8%).6 Unfortunately, in Northeast of Mexico, which includes States that are located in the border with USA, there is a little information about frequency of HCV genotypes, and clinical and demographic data in patients infected with HCV.13 In this study we report the distribution of HCV genotypes and the principal risk factors in HCV infected patients from Northeast of Mexico.

Material and methodsPatientsWe included 147 HCV-infected patients [65 males and 82 females, mean age 44 ± 12 years (range 19-74)] that were enrolled from the Infectious Diseases and Liver Unit from Internal Medicine Department at the University Hospital «Dr. José E. González», and community-based out-reach facilities in Monterrey. This public hospital, with 500 beds, is the largest in Northeast Mexico with patients coming principally from the State of Nuevo Leon and surrounding states in Northern Mexico (Coahuila, Tamaulipas and San Luis Potosi). Clinical and demographic data were collected through a standardized questionnaire. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards. At enrollment, all participants signed the informed consent.

Serological analysisTen milliliters of blood were taken from each patient to perform biochemical, serological and molecular tests. Repeated freeze-thaw cycles were avoided to optimize RNA isolation and the tests were performed in duplicate. The diagnosis of HCV infection was confirmed by the presence of anti-HCV antibodies and HCV-RNA in the serum. Anti-HCV detection was carried out by a third-generation enzyme immunoassay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Abbot, North Chicago, IL).

RNA isolationTotal RNA was isolated from serum samples by a modified version of the acid guanidinium–phenol–chloroform method.14 Briefly, 400 • • L of serum was mixed with 600 • • L of Trizol LS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Then 200 • • L of chloroform was added and the mixture was incubated for 10 min at 4 °C, and then centrifuged. Total RNA was precipitated from the aqueous phase using 600 • • L of isopropanol. Finally, RNA pellet was briefly air-dried, dissolved in diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water.

cDNA synthesis and PCR amplificationComplementary DNAs (cDNAs) were synthesized at 42 °C for 60 minutes with 3 • • L of RNA solution and 200 U/• • L of Superscript II enzyme in a 20 • • L reaction mixture containing 0.15 • • g/• • L random primers, first strand buffer 1X, 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.5 mM dNTPs, and 2 U/• • L RNAse inhibitor, then incubated at 94 °C for 5 minutes. The resultant cDNAs were subsequently amplified with Taq DNA polymerase (Epicentre, Madison, WI, USA) by nested PCR using primers to amplify a portion of 5' untranslated region (UTR) of the HCV genome. Primers for the first round of PCR were: sense primer HCV-U1 5'-CTGTGAGGAACTACTGTCTTC-’3 and antisense primer HCV-D2 5'- CAACACTACTCGGCTAGCAGT-’3. For the second round of PCR a set of sense primer HCV1-N3 5'-ACGCAGAAAGCGTCTAGCCAT-3' and antisense primer HCV-N4 5'-ACTCGGCTAGCAGTCTTGCGG-3' were used. PCR was performed by 35 cycles; each one consisting of 2 minutes at 94 °C followed by cycles of 94 °C for 1 minute, 58 °C for 1 minute and 72 °C for 1 minute and finally at 72 °C for 10 minutes. In the second round of PCR 1 • • L of product of the first PCR was mixed with 49 • • L of the PCR mix and amplified as indicate above. Two PCR products (221 and 194 bp, first and second PCR, respectively) were visualized in UV light by using a 2% agarose gel.

Genotyping analysisWe used the reverse hybridization Inno-Lipa HCV II assay (Innogenetics-Bayer, Antwerp, Belgium) to identify HCV genotypes in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The HCV genotype nomenclature used in this study is that proposed recently by an international panel.9

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics was used (mean and standard deviation). The chi-square or Fisher exact tests were used to detect differences. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

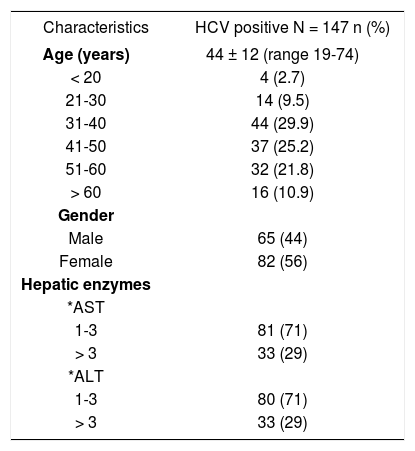

ResultsDemographic and clinical characteristicsThe major demographic and clinical characteristics of the 147 chronic HCV infected patients studied [65 males and 82 females, mean age 44 ± 12 years (range 19-74)] are presented in Table I. The histological data showed that most of the patients had chronic hepatitis (63%), while the remainder presented cirrhosis (37%). Our results showed that the proportion of HCV patients with HCV treatment was 37%. On the other hand, a demographic survey demonstrated that all patients were natives and/or residents of Northeast Mexico (states of Nuevo Leon, Coahuila, Tamaulipas and San Luis Potosi).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of HCV patients.

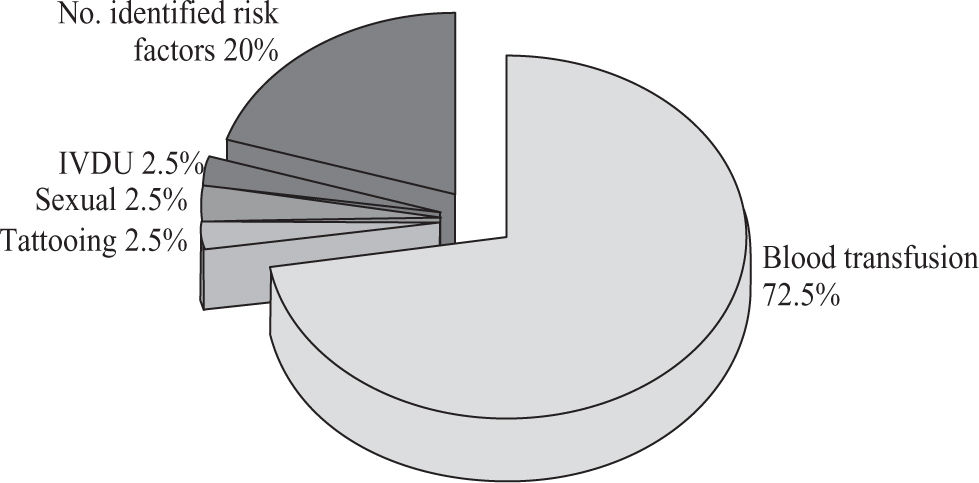

In this study blood transfusion emerged as relevant risk factor for HCV infection (72.5%), followed by intravenous drug users (IVDU; 2.5%), sexual preference (2.5%) and tattooing (2.5%). No risk factors were identified in 20% of the patients(Figure 1).

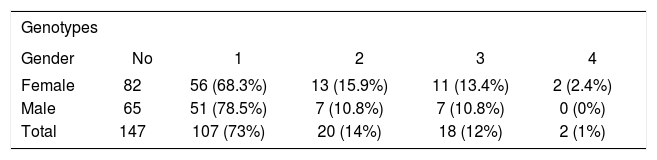

HCV genotypingIn the 147 HCV infected patients analyzed in this study we found that the most frequent HCV genotype was 1 (73%), followed by 2 (14%), 3 (12%) and 4 (1%). The distribution was the following: genotype 1 (2.7%), 1a (28.6%), 1b (37.4%), 1a/1b (4.1%), 2a (1.4%), 2b (8.8%), 2c (0.7%), 2a/2c (2.7%), 3 (2%), 3a (10.2%), 4 (0.7%) and 4c (0.7%)(Table II). Distribution of genotypes according to gender is showed inTable III.

The mechanism of unsuccessful therapy and resistance to pegylated INF-• •in HCV patients are not well understood, but there are several evidences suggesting that virus genome variability contributes to this failure.15 The estimated prevalence of HCV infection varies from 1% in Europe, 1.7% in America, and up to 5.3% in Africa.16 In Mexico HCV prevalence is 1.4% in general population,2 but in high risk populations the prevalence is higher (blood-transfused patients, health personnel, intravenous drug users, individuals with high-risk sexual behaviors). Information about prevalence, genotypes and risk factors in HCV infected patients in Northeast of Mexico (including states of Nuevo Leon, Coahuila, Tamaulipas and San Luis Potosi) is limited.13,18

The results from this study are similar to those reported previously in other Mexican regions where the predominant genotype is 1 (72.2%), followed by genotype 2 (18%) and 3 (9.8%).6 The genotype pattern was also similar to that observed in other reports of Latin America where genotype 1 is highly prevalent, followed by genotypes 2 and 3, and other genotypes are less frequent (genotypes 4 and 5).10-12

The risk factors for HCV transmission have changed over the past two decades. Currently, HCV is rarely transmitted by blood transfusion in developed countries, where HCV screening in the blood bank started since 1990, while in our country such screening started until 1995.19 However, in this study a history of blood transfusion (72.5%) still emerged as relevant risk factors for HCV infection, followed by IVDU (2.5%), sexual preference (2.5%) and tattooing (2.5%). No risk factors were identified in 20% of the patients(Figure 1). Intravenous drug use is uncommon in our country; it could explain the low frequency found in our studied population (2.5%). In contrast, intravenous drug use currently accounts for most HCV transmission in the US.19

In conclusion, we found that infected individuals were more likely to be female (56%). The most frequent HCV genotype was 1 (73%), followed by 2 (14%), 3 (12%) and 4 (1%). Also, we found that a history of blood transfusion emerged as relevant risk factor for HCV infection. Therefore, we highly recommended characterizing the genotype because is an important tool not only for HCV therapy but also for epidemiological studies.

AcknowledgmentsWe are especially grateful to the medical and technical staff of the Infectology Service and Liver Unit from Internal Medicine Department of the University Hospital of UANL. This work was supported by grants from: CONACyT (SALUD-2003-C01-02/A1) and from the Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon (PAICYT-SA1161-05) to AMR and SA607-01 to LME.