Background. Approximately 180 million persons (∼2.8%) globally are estimated to be infected by hepatitis C virus (HCV). HCV prevalence in Mexico has been estimated to be between 1.2 and 1.4%. The aim of present work was to determine the prevalence of HCV infection in patients and family members attending two primary care clinics in Puebla, Mexico.

Material and methods. Patients and their accompanying family members in two clinics were invited to participate in this study between May and September 2010.

Results. A total of 10,214 persons were included in the study; 120 (1.17%) persons were anti-HCV reactive. Of the reactive subjects, detection of viral RNA was determined in 114 subjects and 36 were positive (31%). The more frequent risk factors were having a family history of cirrhosis (33.1%) and having a blood transfusion prior to 1995 (29%). After a multiple logistic regression analysis only transfusion prior to 1995 resulted significant to HCV transmission (p = 0.004). The overall detected HCV genotypes were as follows: 1a (29%), 1b (48.5%), 2/2b (12.8%), and 3a (6.5%).

Conclusion. The HCV prevalence in this population is in agreement with previous studies in other regions of Mexico.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is an important public health concern. Worldwide, 180 million persons (prevalence ~2.8%) are estimated to be infected.1 The primary diseases associated with HCV are chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.2

The actual prevalence of HCV is difficult to assess because serological tests do not discriminate among acute, chronic, or resolved infection, and the analyzed groups in most countries are not representative of the general population, such as blood donors, drug users, or individuals with high-risk sexual practices.3–5 In Latin America, HCV infection represents a serious health problem, calculating the overall HCV seroprevalence to be ~1.5%.6 It is estimated that the incidence of hepatitis C in Mexico ranges from 17,500 to 35,000 new cases of infected individuals each year.7

In Mexico, the prevalence of HCV is 1.2-1.4% in the open population and 30-35% in patients with active hepatitis.8–10 In Mexico, cirrhosis has shown an increasing tendency, rising from 12,058 cases in 2005 to 12,996 cases in 2006. In addition, cirrhosis is the second cause of death in the 15- to 64-year-old age group, being three times higher in males than in females. Puebla is the Mexican state with the highest mortality due to hepatic cirrhosis.11,12 Therefore, it is imperative to obtain epidemiological data on the asymptomatic population, which may contribute to determine, in part, the possible causes of the high incidence of hepatic diseases in this region. In this work we analyzed the prevalence of HCV and the main risk factors in patients and accompanying family members attending two primary care clinics.

Material and MethodsParticipantsPatients and family members or accompanying persons attending Clinics #6 and #55 located in the city of Puebla were invited to participate in the study between May and September 2010. There were no formal exclusion criteria but any one individual could be included only once. Subjects received a patient information sheet (Letter of Informed Consent) and a study-specific questionnaire. We obtained complete and reliable individual patient information (age, sex, health insurance and risk factors). This information was used to describe any relationship with HCV infection.

TestingThe initial screening of Anti-HCV reactivity of volunteers was carried out using Advanced Quality Rapid anti-HCV Test (Accutrack, Mexico, D.F., Mexico), which consists of a cartridge in which are present antigenic recombinant peptides corresponding to core, NS3, NS4 and NS5A proteins, highly reactive to anti-HCV. The test is based on immunochromatografy and is completed in 15 min. A drop of total blood (10 µL) was obtained of a puncture in the distal portion of the fifth finger of the any hand, which was applied on the well of the cartridge, immediately were added two drops of diluents; the test consider a reactive sample if a purple band is formed. Blood samples from peripheral vein were taken to reactive subjects and then were submitted to detection of viral RNA by using COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan HCV Test (Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France). Genotypes were determined by Versant HCV Genotype 2.0 Assay (LiPA, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NY, U.S.A.).

Statistical analysisFor continuous variables, averages, frequencies and percentages were calculated. Associations between anti-HCV and HCV-RNA positivity were assessed using χ2 and Fisher’s Exact Tests. Associations between HCV RNA and risk factors were assessed by univariate (χ2 and Fisher’s Exact tests) and multivariate analysis (logistic regression). Logistic regression was performed when the potential risk factors had values of p ≤ 0.1 by univariate analysis. Statistical significance was defined as p ≤ 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics version 21.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

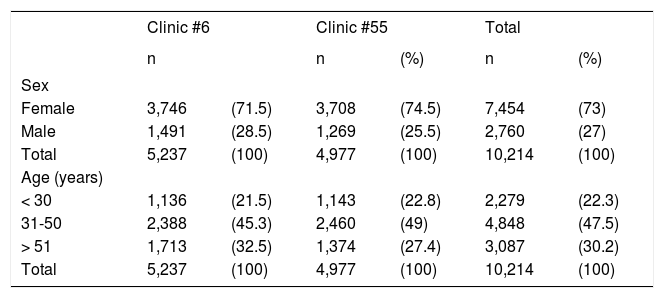

ResultsSeroprevalence of HCVThere were 5,237 samples obtained from Clinic #6 and 4,977 samples from Clinic #55, resulting in 10,214 persons. There were 7,454 (73%) females and 2,760 (27%) males with the most frequent age range in both clinics between 31 and 50 years (Table 1). Sixty persons from each clinic were positive to anti-HCV antibodies, maintaining the female population as more frequent: 47/60 (78%) and 46/60 (76.7%). These data show that female/male ratio in reactive individuals is similar to that of the studied population. Seroprevalence was 1.14% in Clinic #6 and 1.20% in Clinic #55; overall prevalence was 1.17% (120/10, 2014).

Demographic data of the studied subjects from Clinics #6 and #55 in Puebla, Mexico.

| Clinic #6 | Clinic #55 | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 3,746 | (71.5) | 3,708 | (74.5) | 7,454 | (73) |

| Male | 1,491 | (28.5) | 1,269 | (25.5) | 2,760 | (27) |

| Total | 5,237 | (100) | 4,977 | (100) | 10,214 | (100) |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| < 30 | 1,136 | (21.5) | 1,143 | (22.8) | 2,279 | (22.3) |

| 31-50 | 2,388 | (45.3) | 2,460 | (49) | 4,848 | (47.5) |

| > 51 | 1,713 | (32.5) | 1,374 | (27.4) | 3,087 | (30.2) |

| Total | 5,237 | (100) | 4,977 | (100) | 10,214 | (100) |

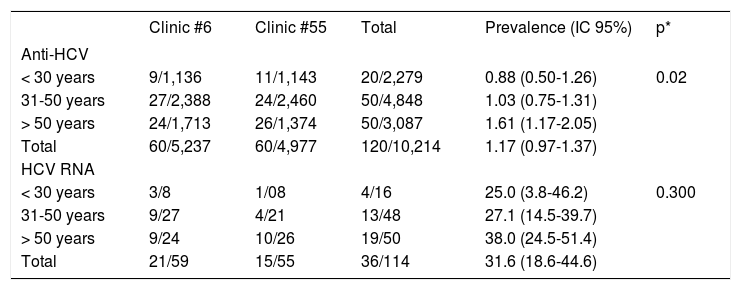

Anti-HCV positivity was different according with the age group (Table 2), and ranged from 0.88% in < 30 years subjects to 1.61% in > 50 years subjects (p = 0.02).

Prevalence of Anti-HCV and HCV RNA in the studied subjects from Clinics #6 and #55 in Puebla, Mexico, grouped by age.

| Clinic #6 | Clinic #55 | Total | Prevalence (IC 95%) | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-HCV | |||||

| < 30 years | 9/1,136 | 11/1,143 | 20/2,279 | 0.88 (0.50-1.26) | 0.02 |

| 31-50 years | 27/2,388 | 24/2,460 | 50/4,848 | 1.03 (0.75-1.31) | |

| > 50 years | 24/1,713 | 26/1,374 | 50/3,087 | 1.61 (1.17-2.05) | |

| Total | 60/5,237 | 60/4,977 | 120/10,214 | 1.17 (0.97-1.37) | |

| HCV RNA | |||||

| < 30 years | 3/8 | 1/08 | 4/16 | 25.0 (3.8-46.2) | 0.300 |

| 31-50 years | 9/27 | 4/21 | 13/48 | 27.1 (14.5-39.7) | |

| > 50 years | 9/24 | 10/26 | 19/50 | 38.0 (24.5-51.4) | |

| Total | 21/59 | 15/55 | 36/114 | 31.6 (18.6-44.6) |

RT-PCR was performed in 59/60 HCV-reactive persons in Clinic #6 and 21 (35.6%) resulted to be HCV RNA positive. In subjects from Clinic #55, RT-PCR was performed in 55/60 of HCV-reactive subjects, of which 15 (27.3%) were HCV RNA positive. In both clinics a total of 114 RT-PCR tests were carried out for same number of subjects and 36 (31.6%) were positive. In the case of HCV-RNA positivity, no significant difference was observed in the age groups, however a trend to increase in the > 50 years group was noticed: 38 vs. 25% and 27.1% of groups of < 30 years and 31-50 years, respectively (Table 2).

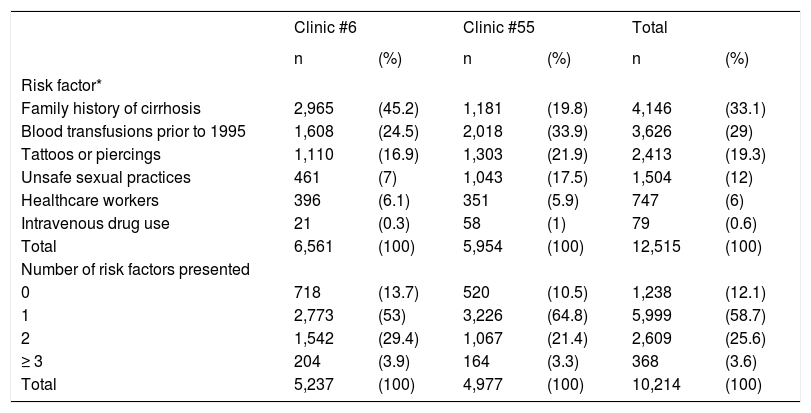

Risk factorsThe main risk factors in subjects were a family history of cirrhosis (33.1%) and blood transfusions prior to 1995 (29%), followed by use of tattoos and piercings, high-risk sexual behavior, or healthcarerelated occupation. Most of subjects presented only 1 risk factor (58.7%), while those which presented ≥ 3 risk factors were 3.6% only (Table 3).

Risk factors in the studied subjects from Clinics #6 and #55 in Puebla, Mexico.

| Clinic #6 | Clinic #55 | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Risk factor* | ||||||

| Family history of cirrhosis | 2,965 | (45.2) | 1,181 | (19.8) | 4,146 | (33.1) |

| Blood transfusions prior to 1995 | 1,608 | (24.5) | 2,018 | (33.9) | 3,626 | (29) |

| Tattoos or piercings | 1,110 | (16.9) | 1,303 | (21.9) | 2,413 | (19.3) |

| Unsafe sexual practices | 461 | (7) | 1,043 | (17.5) | 1,504 | (12) |

| Healthcare workers | 396 | (6.1) | 351 | (5.9) | 747 | (6) |

| Intravenous drug use | 21 | (0.3) | 58 | (1) | 79 | (0.6) |

| Total | 6,561 | (100) | 5,954 | (100) | 12,515 | (100) |

| Number of risk factors presented | ||||||

| 0 | 718 | (13.7) | 520 | (10.5) | 1,238 | (12.1) |

| 1 | 2,773 | (53) | 3,226 | (64.8) | 5,999 | (58.7) |

| 2 | 1,542 | (29.4) | 1,067 | (21.4) | 2,609 | (25.6) |

| ≥ 3 | 204 | (3.9) | 164 | (3.3) | 368 | (3.6) |

| Total | 5,237 | (100) | 4,977 | (100) | 10,214 | (100) |

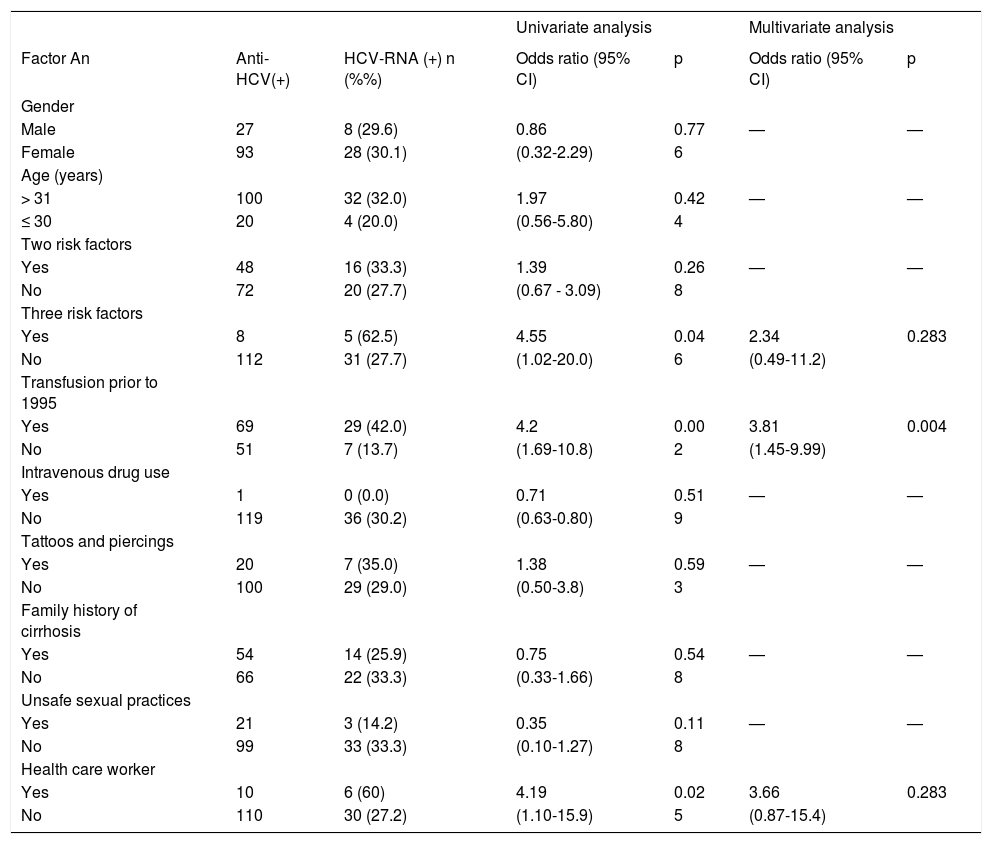

By univariate analysis we determined that having ≥ 3 risk factors (62.5 vs. 27.7%; p = 0.046), blood transfusion prior 1995 (42.0 vs. 13.7%; p = 0.002) or to be health worker (60 vs. 27.2%; p = 0.025) are significantly associated with HCV RNA positivity (Table 4). After a multiple logistic regression analysis only transfusion prior to 1995 may significantly contribute to HCV transmission (p = 0.004). The importance of this risk factor (odds ratio) was 3.81 and is presented with other potential risk factors in the table 4.

Risk factors in HCV-RNA positive subjects from Clinics #6 and #55 in Puebla, Mexico.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor An | Anti-HCV(+) | HCV-RNA (+) n (%%) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 27 | 8 (29.6) | 0.86 | 0.77 | — | — |

| Female | 93 | 28 (30.1) | (0.32-2.29) | 6 | ||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| > 31 | 100 | 32 (32.0) | 1.97 | 0.42 | — | — |

| ≤ 30 | 20 | 4 (20.0) | (0.56-5.80) | 4 | ||

| Two risk factors | ||||||

| Yes | 48 | 16 (33.3) | 1.39 | 0.26 | — | — |

| No | 72 | 20 (27.7) | (0.67 - 3.09) | 8 | ||

| Three risk factors | ||||||

| Yes | 8 | 5 (62.5) | 4.55 | 0.04 | 2.34 | 0.283 |

| No | 112 | 31 (27.7) | (1.02-20.0) | 6 | (0.49-11.2) | |

| Transfusion prior to 1995 | ||||||

| Yes | 69 | 29 (42.0) | 4.2 | 0.00 | 3.81 | 0.004 |

| No | 51 | 7 (13.7) | (1.69-10.8) | 2 | (1.45-9.99) | |

| Intravenous drug use | ||||||

| Yes | 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0.71 | 0.51 | — | — |

| No | 119 | 36 (30.2) | (0.63-0.80) | 9 | ||

| Tattoos and piercings | ||||||

| Yes | 20 | 7 (35.0) | 1.38 | 0.59 | — | — |

| No | 100 | 29 (29.0) | (0.50-3.8) | 3 | ||

| Family history of cirrhosis | ||||||

| Yes | 54 | 14 (25.9) | 0.75 | 0.54 | — | — |

| No | 66 | 22 (33.3) | (0.33-1.66) | 8 | ||

| Unsafe sexual practices | ||||||

| Yes | 21 | 3 (14.2) | 0.35 | 0.11 | — | — |

| No | 99 | 33 (33.3) | (0.10-1.27) | 8 | ||

| Health care worker | ||||||

| Yes | 10 | 6 (60) | 4.19 | 0.02 | 3.66 | 0.283 |

| No | 110 | 30 (27.2) | (1.10-15.9) | 5 | (0.87-15.4) | |

Univariate analysis: Fisher’s exact test. Multivariate analysis: logistic regression.

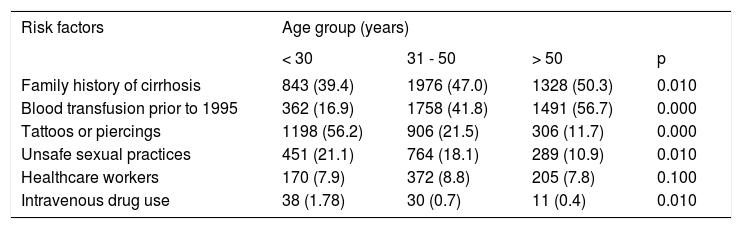

In the univariate analysis (Table 5), the independent variable of family history of cirrhosis was associated with age groups of > 31-50 and > 50 years (47.0 and 50.3% respectively vs. 39.4% of < 30 years group; p = 0.010), while blood transfusion prior 1995 was associated with > 31-50 years and > 50 years groups (41.8 and 56.7% respectively vs. 16.9% of < 30 years group, p = 0.000). In contrast, tattoos and piercings were associated with the age group of < 30 years (56.2 vs. 21.5% and 11.7% of groups of 31-50 years and > 50 years, respectively; p = 0.000), unsafe sexual practices was also associated with the group age of < 30 years (21.1 vs. 10.9% of group > 50 years; p = 0.010). The < 30 years group was also associated with intravenous drug use (1.7 vs. 0.7% and 0.4% of groups age > 31-50 years and > 50 years respectively; p = 0.010).

Risk factors in subjects from Clinics #6 and #55 in Puebla, Mexico grouped by age.

| Risk factors | Age group (years) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 30 | 31 - 50 | > 50 | p | |

| Family history of cirrhosis | 843 (39.4) | 1976 (47.0) | 1328 (50.3) | 0.010 |

| Blood transfusion prior to 1995 | 362 (16.9) | 1758 (41.8) | 1491 (56.7) | 0.000 |

| Tattoos or piercings | 1198 (56.2) | 906 (21.5) | 306 (11.7) | 0.000 |

| Unsafe sexual practices | 451 (21.1) | 764 (18.1) | 289 (10.9) | 0.010 |

| Healthcare workers | 170 (7.9) | 372 (8.8) | 205 (7.8) | 0.100 |

| Intravenous drug use | 38 (1.78) | 30 (0.7) | 11 (0.4) | 0.010 |

Univariate analysis was performed and p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

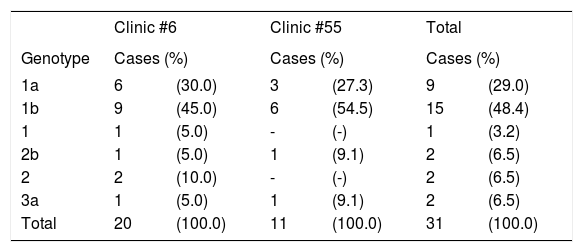

HCV genotypes and subtypes were determined in 31/36 HCV-RNA positive subjects (Table 6). The most frequent genotype in both clinics was 1b (45 and 54.5%, respectively) followed by 1a (30 and 27.3%, respectively). Genotypes 2, 2b and 3a were found in a minor proportion, and genotypes 4, 5 and 6 were not found. Overall frequencies (total of two clinics) were as follows: 25 (80.6%) subjects had HCV genotype 1, of which 15 (48.4%) had subtype 1b and 9 (29%) had subtype 1a; two subjects had subtype 2b (6.5%) and another two (6.5%) had genotype 2 and undetermined subtype, whereas two (6.5%) subjects had subtype 3a.

Genotype and subtype of HCV in 30 of HCV-RNA-positive subjects from Clinics #6 and #55 in Puebla, Mexico.

| Clinic #6 | Clinic #55 | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Cases (%) | Cases (%) | Cases (%) | |||

| 1a | 6 | (30.0) | 3 | (27.3) | 9 | (29.0) |

| 1b | 9 | (45.0) | 6 | (54.5) | 15 | (48.4) |

| 1 | 1 | (5.0) | - | (-) | 1 | (3.2) |

| 2b | 1 | (5.0) | 1 | (9.1) | 2 | (6.5) |

| 2 | 2 | (10.0) | - | (-) | 2 | (6.5) |

| 3a | 1 | (5.0) | 1 | (9.1) | 2 | (6.5) |

| Total | 20 | (100.0) | 11 | (100.0) | 31 | (100.0) |

Genotypes were determined by Versant HCV Genotype 2.0 Assay.

The viral load was analyzed in every genotyped HCV positive subject. These subjects were then prescribed medical treatment. The lowest viral load detected among all subjects was 4.24 log and the highest was 6.8 log, corresponding with genotypes 1a and 3a, respectively (data not shown). Statistical analysis searching for a relation between viral load and genotype was not performed due to the low number of cases.

DiscussionIn the present study we identified HCV seroprevalence, genotype and the main risk factors in patients and family members attending two clinics of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS) in the city of Puebla, Mexico. Seroprevalence was 1.14% in Clinic #6 and 1.20% in Clinic #55. In Mexico, a prevalence of HCV infection has been reported to be between 0 and 2%, fluctuating between blood donors and the open population.9,10,13,14 In other populations may be higher, such as non-injection drug users (4.1%),15 hemodialysis patients (6.7%)16 or injection drug users (96%).17

With respect to HCV genotypes, the present study is similar to other previously published studies.9,18–24 The most frequent subtypes in Mexico are 1a and 1b, which has clinical relevance because genotype 1 has been reported as highly resistant to standard peginterferon/ribavirin therapy. Detection of persons infected with this genotype represents a preventive method to refer the patients to the corresponding clinic and begin their treatment during the acute phase.

We found that the principal risk factors were having family members with cirrhosis (33.1%) and having blood transfusion prior 1995 (29%). However, only blood transfusions prior 1995 significantly contribute to HCV transmission (p = 0.004). This result indicates that the principal risk factor in Mexico is still transfusions prior to 1995 because the official Mexican NOM-003-SSA2-1993, which determines detection of HCV antibodies in blood banks, was published on July 18, 1994.7 Risk factors are dependent on the lifestyle of the individual. In developed countries, the principal risk factor is drug use, whereas in developing countries blood transfusions are still an important risk factor14,25 however, some studies finding no statistical association between HCV infection and blood transfusion.26

An additional aspect derived from this study is the possibility of sampling diverse asymptomatic subjects in order to detect HCV-infected persons who then can be referred for timely medical treatment.

ConclusionIn the present study we determined a seroprevalence of 1.17%, whereas 31% of these reactive subjects were positive to viral RNA. The main risk factor detected was blood transfusion prior to 1995. The detected HCV genotypes were 1a (29%), 1b (48.5%), 2/2b (12.8%), and 3a (6.5%). The prevalence in this population is in agreement with previous studies in other Mexican regions.

Abbreviations- •

HCV: hepatitis C virus

- •

RT-PCR: reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

This work was supported by the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, FIS/IMSS/PROT/G11/830.