Background and aim. The aim of this study is to evaluate the role of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC).

Material and methods. On the basis of a retrospective review of medical records, all patients consecutively diagnosed with PBC or HCV infection between 1999 and 2011 and who had a regular follow-up of at least 3 years were included in the study. Clinical characteristics, especially the severity of cirrhosis, were analyzed in PBC patients with HCV infection (PBC-HCV), PBC patients without HCV infection (PBC-only), and patients with only HCV infection (HCV-only).

Results. A total of 76 patients with PBC, including 9 patients with HCV infection, were analyzed. Of the PBC-HCV patients, 7 (7/9, 77.8%) were women with a mean age of 55.11 ± 14.29 years. Age- and sex-matched PBC-only patients (n = 36) and HCV-only patients (n = 36) were used as control groups. In comparison to the PBC-only controls, PBC-HCV patients had a greater severity of cirrhosis based on Child-Pugh (p = 0.019) and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) (p = 0.01) scores. However, no significant difference in the severity of cirrhosis was found between the PBC-HCV and HCV-only control patients (p = 0.94 in Child-Pugh scores; p = 0.64 in MELD scores).

Conclusions. In PBC patients with concomitant HCV infection, aggressive management may be warranted in view of the associated more severe liver cirrhosis.

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a chronic, progressive cholestatic liver disease without definitively known etiologies and often presents with inflammatory destruction of bile ducts leading to cirrhosis.1 PBC is also a rare disease with an overall age- and sex-adjusted annual incidence rate of 30.3 cases per million.2 Serologically, PBC is characterized by the presence of antimitochondrial antibodies, which are present in 90–95% of patients. Originally, PBC was described as an autoimmune disorder with the presentation of jaundice and pruritus.3 Ursodeoxy-cholic acid is currently the only drug approved worldwide for the treatment of PBC, which delays the histological progression of the disease.4

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a leading cause of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and liver cancer worldwide.5 The mechanism of HCV-triggered liver injury is not well understood; however, recent studies suggest that cellular immunity not only plays a protective role but also causes liver injury. The pathogenesis of cirrhosis is related to chronic inflammation and immune reaction. The current medication is a combination of pegylated interferon (IFN) and the antiviral drug, ribavirin. In addition to liver injury, HCV infection also causes disturbance of the immune system and is associated with various autoimmune disorders (type 1 or 2 autoimmune hepatitis, Sjögren’s syndrome, lichen planus, mixed cryoglobulinemia, and autoimmune thyroiditis).6–8 Therefore, hepatitis C can be regarded as a virus related autoimmune hepatitis. In the course of progression to cirrhosis, both PBC and HCV infection present with chronic inflammation.

Floreani, et al.9 analyzed patients with both PBC and HCV infection (PBC-HCV) and found that HCV infection was a risk factor for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in this overlap group. However, the role of HCV infection in cirrhosis severity has not yet been elucidated; hence, we analyzed the relationship between HCV infection and PBC to demonstrate the effect of HCV infection on the severity of cirrhosis in patients with PBC.

Material and MethodsSubjectsFrom January 1999 to December 2011, we analyzed a total of 76 hospitalized patients with PBC. All PBC patients met at least 2 of the following criteria: antimitochondrial antibody titer of at least 1:80, abnormal liver function tests (alkaline phosphatase) for > 6 months, and diagnostic or compatible liver biopsy.1 Nine of the 76 (11.84%) patients were found to have HCV infection (7 women and 2 men) on the basis of positive anti-HCV/HCV RNA, and only 1 patient (1.31%) was found to have hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection on the basis of positive HBV surface antigen. Patients with PBC were classified into 2 groups according to the presence of HCV infection: HCV-infected group (9 patients, PBC-HCV) and PBC-only control group (36 patients with age-and sex-matched frequencies from the remaining 67 patients without HCV infection). Patients with only HCV infection (36 patients with age- and sex-matched frequencies from HCV-only patients not receiving anti-HCV therapy in our medical center between January 1999 and December 2011) were identified as the HCV-only control group.

Study designThis study was a 12-year retrospective observation. We collected data according to each patient’s demographic characteristics, including diagnostic age, gender, laboratory profiles, Child-Pugh (C-P) classification of cirrhosis, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores, presence of major events (bleeding inclusive of esophageal varices or gastric varices, ascites, HCC, extrahepatic cancer, and death), autoimmune diseases (scleroderma, Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), thyroid disorder, and type 2 diabetes mellitus), and survival observation time. The survival observation time was set to be 3 years (156 weeks). The severity of cirrhosis was based on the C-P classification and MELD scores. MELD score I is defined as having a score of < 9, MELD score II is defined as a score of 10–19, MELD score III is defined as a score of 20–29, MELD score IV is defined as a score of 30–39, and MELD score V is defined as a score of ≥ 40; the classification (I–V) of MELD scores is based on the predictive outcome of 3-month mortality (I: 1.9% mortality, II: 6.0% mortality, III: 19.6% mortality, IV: 52.6% mortality, V: 71.3% mortality).10 In the C-P classification, classification A is defined as having a score of 5–6, classification B is a score of 7–9, and classification C is a score of 10–15.

Data analysesContinuous variables are expressed as means ± SD. The results for categorical variables are expressed as percentages. Statistical comparisons between the groups were computed using the Student’s t test or the χ2 test, according to the type of data. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated to examine the effect of HCV infection on the severity of cirrhosis in patients with PBC, according to the level of C-P classification of cirrhosis. Survival rates were computed by Kaplan-Meier methods, followed by a log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard model was used to calculate the effect of factors on survival. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and STATA software version 8.0. All reported p values are 2-tailed, and p < 0.05 was assumed statistically significant for all tests.

ResultsAfter inclusion of 36 age- and sex-matched PBC-only patients for PBC-HCV controls, the other 31 PBC-only patients were excluded in this study. In addition to an older diagnostic age of the excluded PBC-only patients vs. PBC-only controls (p = 0.03), there are no other significant differences of clinical characteristics between these two groups.

PBC has a female predominance, and most patients in the study were > 50 years old at initial diagnosis (mean, 55.11 years in the PBC-HCV group vs. 56.17 years in the PBC-only group). Of the 9 patients with PBC-HCV, 5 (55.55%) had C-P classification of B. However, 26 of the 36 (72.2%) PBC-only patients had a C-P classification of A. A significant difference in cirrhosis severity was found between the 2 groups (p = 0.019). HCV infection was associated with a more severe C-P classification of cirrhosis (C-P classification B vs. C-P classification A: OR 8.13, 95% CI 1.10-60.03, p = 0.014; C-P classification C vs. C-P classification A: OR 13.0, 95% CI 0.84-200.07, p = 0.017; test for trend, p < 0.01). In the PBC-HCV group, most patients (66.7%) had a MELD score II; PBC-only patients mostly had MELD score I (66.7%). A significant difference was observed in the MELD scores classification (p = 0.01). The PBC-HCV group had poorer laboratory variables (albumin, total bilirubin, international normalized ratio, creatinine, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and gamma-glutamyltransferase) (Table 1). The clinical and virological details of the PBC-HCV patients are summarized in table 2.

Clinical characteristics of PBC patients.

| PBC-HCV (n = 9) | PBC-only (n = 36) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (diagnosis of PBC) | 55.11 ± 14.29 | 56.17 ± 12.39 | 0.826 |

| Female | 7 (77.7%) | 28 (77.7%) | 1 |

| MELD scores (I/II/III/IV) (%) | 11.1/66.7 / 11.1/11.1 | 66.7/27.8/5.6 | 0.01* |

| C-P classification (A/B/C) (%) | 22.2 / 55.5/22.2 | 72.2 / 22.2/5.6 | 0.019* |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 2.95 ± 0.49 | 3.52 ± 0.67 | 0.022* |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 5.28 ± 7.91 | 2.27 ± 3.10 | 0.294 |

| International normalized ratio (INR) | 1.34 ± 0.29 | 1.12 ± 0.17 | 0.061 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.08 ± 0.72 | 0.82 ± 0.31 | 0.319 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L) | 262.5 ± 234.12 | 95.94 ± 121.69 | 0.068 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 221.2 ± 247.09 | 89.67 ± 100.01 | 0.153 |

| Gamma-glutamyltransferase (mg/dL) | 471.4 ± 448.16 | 198.0 ± 148.17 | 0.246 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 377.1 ± 38.7 | 296.7 ± 260.6 | 0.36 |

| Platelet count (×103 mm-3) | 190.1 ± 87.15 | 152.0 ± 58.87 | 0.128 |

| Anti-nuclear antibody (+) | 2 (22.2%) | 15 (41.7%) | 0.489 |

HCV: hepatitis C virus. PBC: primary biliary cirrhosis. MELD scores: Model for End-Stage Liver Disease scores. C-P classification: Child-Pugh (C-P) classification.

Clinical characteristics of HCV-infected PBC patients.

| No. | Gender | Inf age of HCV (y) | Dx age of HCV (y) | Dx age of AMA PBC (y) | Dx age of IgM titer | g /dL | HCV-RNA (cps/mL) | Source of infection | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | N/A | 63 | 66 | 1: 160 | 2.8 | 2.11 ×106 | Glass syringe | Alive (>156 wks) |

| 2 | F | N/A | 61 | 63 | 1: 320 | 4.7 | 2.61 ×106 | Glass syringe | Alive (>156 wks) |

| 3 | F | 28 | 50 | 53 | 1: 80 | 5.6 | 3.1 × 106 | Glass syringe | Alive (>156 wks) |

| 4 | M | 26 | 42 | 45 | 1: 320 | 2.8 | 9.33 ×106 | Glass syringe | Alive (>156 wks) |

| 5 | F | N/A | 63 | 63 | 1: 640 | 2.7 | 1.6 ×106 | Glass syringe | Alive (>156 wks)* |

| 6 | F | 54 | 71 | 71 | 1: 160 | 7.6 | 2.21 ×106 | Transfusion | Sepsis (71 wks) |

| 7 | M | 8 | 23 | 23 | 1: 320 | 2.9 | 2.3 ×106 | Glass syringe | Alive (>156 wks)* |

| 8 | F | N/A | 56 | 56 | 1: 640 | 4.5 | 2.42 ×106 | Glass syringe | Sepsis (56 wks) |

| 9 | F | N/A | 56 | 56 | 1: 160 | 2.9 | 4.12 ×106 | Glass syringe | Breast CA (38 wks) |

No: number. Dx: diagnosis. Cps: copies per mL. CA: cancer. N/A: non-available. Inf: infection. AMA: anti-mitochondrial antibody.

Table 3 summarizes the associated major events and autoimmune disorders in the presentation. Between the 2 groups, HCC was noted with a higher incidence rate in the PBC-HCV group (11.11% vs. 2.8%). Ascites also seemed to be more common in PBC-HCV patients. There was no significant difference in the association of autoimmune disorders in the 2 groups. The most representative disorder was Sjögren’s syndrome. In the analysis of survival observation time, the PBC-only group showed a slower decline in the curve (Figure 1). Cox regression analysis indicated that high C-P classification scores had an unfavorable effect on survival (hazards ratio 2.57; 95% CI 1.15–5.73; p = 0.021).

Major events and autoimmune diseases of PBC patients (n = 45).

| HCV-infected (n=9) | PBC only (n=36) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| • Major events | |||

| Bleeding | 1 (11.11%) | 7 (19.4%) | 0.922 |

| Ascites | 3 (33.33°%) | 6 (16.7%) | 0.514 |

| HCC | 1 (11.11%) | 1 (2.8%) | 0.856 |

| Extra-hepatic cancer | 1 (11.11%) | 0 | 0.448 |

| Death | 3 (33.33%) | 7 (19.4%) | 0.654 |

| • Autoimmune disorder | |||

| Scleroderma | 0 | 0 | |

| Sjögren’s syndrome | 2 (22.22%) | 6 (16.7%) | 1 |

| SLE | 1 (11.11%) | 0 | 0.448 |

| Raynaud’s disease | 0 | 2 (5.6%) | 1 |

| Thyroid disorder | 1 (11.11%) | 2 (5.6%) | 1 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 1 (11.11%) | 1 (2.8%) | 0.856 |

HCV: hepatitis C virus. PBC: primary biliary cirrhosis. HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma. SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus.

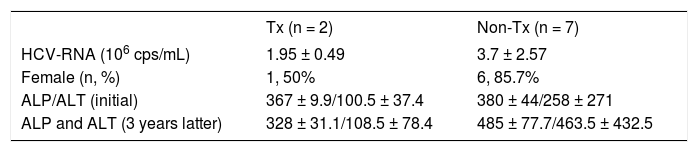

Clinical characteristics of the HCV-infected patients are summarized in the table 4. Two patients receiving treatment with IFN and ribavirin were noted to have lower viral loads. In the analysis of the survival observation time, the HCV-treated group had a slower decline in the curve (Figure 2).

Patients of PBC-HCV receiving anti-HCV treatment versus non-treatment.

| Tx (n = 2) | Non-Tx (n = 7) | |

|---|---|---|

| HCV-RNA (106 cps/mL) | 1.95 ± 0.49 | 3.7 ± 2.57 |

| Female (n, %) | 1, 50% | 6, 85.7% |

| ALP/ALT (initial) | 367 ± 9.9/100.5 ± 37.4 | 380 ± 44/258 ± 271 |

| ALP and ALT (3 years latter) | 328 ± 31.1/108.5 ± 78.4 | 485 ± 77.7/463.5 ± 432.5 |

HCV: hepatitis C virus. PBC: primary biliary cirrhosis. Dx: diagnosis. Tx: treatment. RNA: ribonucleic acid. ALP: alkaline phosphatase (IU/L). ALT: alanine aminotransferase (IU/L).

Table 5 compares the PBC-HCV patients with the HCV-only controls. The severity of cirrhosis was determined by the C-P classification and MELD scores; there was no significant difference between these 2 groups. However, patients with PBC-HCV had higher total bilirubin levels (p = 0.03).

PBC-HCV vs. HCV-only in liver profile.

| HCV-PBC (n = 9) | HCV-only (n = 36) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age55.11 | ±14.29 | 55.22± 13.1 | |

| MELD scores (I/II/III/IV) (%) | 11.1/66.7 | 13.8/61.1 / 22.2/2.7 | 0.64 |

| C-P classification (A/B/C) (%) | 22.2/55.5 /22.2 | 27.7/52.7 / 19.4 | 0.94 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 2.95 ±0.49 | 2.77 ± 0.49 | 0.35 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 5.28 ±7.91 | 2.02 ± 2.13 | 0.03* |

| International normalized ratio (INR) | 1.34 ±0.29 | 1.29 ± 0.38 | 0.68 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.08 ±0.72 | 1.66 ± 1.74 | 0.24 |

HCV: hepatitis C virus. PBC: primary biliary cirrhosis. MELD scores: Model for End-Stage Liver Disease scores. C-P classification: Child-Pugh (C-P) classification.

Previous studies on the occurrence of HCV infection in PBC patients reported incidences of 1 in 90 patients and 3 in 55 patients.11,12 A PubMed search reveals that to date, a total of 23 patients with PBC have been found to have HCV infection.9,13–16 In our research, we have identified an additional 9 patients with a diagnosis of PBC-HCV, and we further discuss here the effect of HCV infection in PBC patients. Among the 76 patients with PBC, approximately 11.84% (9/76) had HCV infection compared with 1.31% (1/76) patients with concomitant HBV infection; however, the prevalence rates of HBV and HCV infections in Taiwan are 15–20% and 1–3%, respectively.17,18 Therefore, there seems to be a close relationship between HCV infection and PBC. Because HCV can lead to immune disorder6–8 and PBC is an autoimmune hepatic disease,3 immune disturbance may underlie this manifestation. Additionally, a comparison between the HCV infection route (through intravenous injection, sexual behavior, or blood transfusion) and the HBV infection route (vertical infection) implicated other infectious agents as the trigger of PBC. Recent studies also support the hypothesis that the development and progression of PBC hinge on a complex interplay between genetic and environmental risk factors.19–22

Comparisons between groups of PBC-HCV, PBC-only and HCV-only patients, with respect to the analysis of cirrhosis severity, indicate that HCV infection aggravates the cirrhosis severity of patients with PBC. The mechanism may be due to the synergic effect from PBC and HCV: PBC is a cholestatic liver disease with the presentation of bile duct destruction and HCV can lead to hepatocyte and parenchyma injury. Ramos-Casals, et al. hypothesized that the coexistence of viral and autoimmune factors may accelerate the development of cirrhosis or neoplasia in such patients.16 Although no significant difference in the severity of cirrhosis was noted between PBC-HCV and HCV-only patients, PBC-HCV patients had higher bilirubin levels (Table 5). We believe that the synergic effect between HCV and PBC may be understood better by studying more cases of PBC-HCV and their respective pathogenesis reported in the future.

In recent studies,23,24 the risk factor for HCC development in patients with PBC was thought to be advanced histological stage, and the incidence rate of HCC in PBC cirrhosis was lower than HCV cirrhosis. Therefore, patients with PBC may have better prognosis than patients with HCV. The results of our study show that in patients with PBC, HCV infection seems to be a risk factor for the development of HCC; this finding is similar to that of a previous study.9 This mechanism may be explained by the role of HCV infection as an exacerbation factor of cirrhosis.

PBC exhibits a number of autoimmune features; in our study, 1 patient was found to have SLE in the HCV-infected group and PBC developed after the SLE diagnosis. The co-occurrence of SLE and PBC is uncommon. Moreover, cases where PBC developed after SLE are rare; in most cases, PBC emerged before SLE.25,26 Of the accompanying autoimmune disorders, Sjögren’s syndrome (8/ 45, 17.77%) is the most representative disorder, similar to the study of Floreani, et al.9, with a prevalence rate of approximately 25%.27

In the analysis of the survival observation time, we found no significant difference between the PBC-HCV and PBC-only patients (Figure 1). However, there seemed to be a trend that the PBC-only group had a slower decline in survival curve than the PBC-HCV group. Cox regression analysis showed that C-P classification was the influencing factor on survival; patients with high C-P scores had unfavorable prognosis on survival. Because both PBC and HCV have a chronic course and HCV can exacerbate the severity of cirrhosis, the difference may be significant with a longer duration of observation and more patients enrolled.

Currently, pegylated interferon (IFN) plus ribavirin become the mainstay of care for HCV infection.28 However, IFN therapy for chronic HCV infection may trigger or exacerbate underlying autoimmune diseases, including PBC,29–31 offering a treatment challenge in PBC-HCV patients. With antiviral therapy, 2 patients of our PBC-HCV group showed a slower decline in survival curve (Figure 2) vs. PBC-HCV patients without treament. Moreover, these patients showed a slower progression of liver injury, according to their serum levels of alkaline phosphatase and alanine transaminase at 3 years after therapy (Table 4). Thus, antiviral therapy may be potentially considered in PBC patients with concomitant HCV infection, in view of the recently emerged watershed in HCV therapy without IFN.32,33

Our study has several limitations. First, this is a non-randomized and retrospective study; thus, unexpected bias may exist. Second, because HCV and HBV have higher prevalence rates than PBC, the primary screening is often anti-HCV/HCV-RNA and HBs-Ag in Taiwan. Thus, most PBC patients are only considered after exclusion of endemic viral hepatitis B and C. This often leads to HCV-infected PBC patients identified after HCV diagnosis, others ignored and the others simultaneously noted with HCV infection by experienced doctors. Third, a compatible liver biopsy can offer more information about the diagnosis and stage of disease. Although liver biopsy has been generally suggested to PBC-HCV patients, most of them refuse this procedure. Thus, the histology severity of PBC cannot be controlled in the analysis of PBC-HCV patients with PBC-only controls. Fourth, the observation time should be longer, which might result in a more significant difference between the 2 groups. Finally and most importantly, only 9 patients are included in the present HCV-infected PBC group; a study with more cases needs to be conducted. In the future, prospective investigations should be conducted to evaluate the effect of different genotypes of HCV infection on PBC patients and to properly manage this overlapping syndrome. Despite these limitations, our study still has clinical implication and is the first study for the role of HCV infection in Asian Chinese PBC patients.

In conclusion, in PBC patients, concomitant HCV infection is characterized by a biochemical profile with poor values of liver markers, especially albumin, and is a risk factor for the development of more severe liver damage versus those without infection.

AcknowledgmentThis study was supported in parts by National Science Council (NSC94-2314-B-016-047), Tri-Service General Hospital, National Defense Medical Center (TSGH-C97-44, TSGH-C98-48 and TSGH-C99-61) and the C.Y. Foundation for Advancement of Education, Sciences and Medicine, Taiwan.