Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of liver cancer in adults and has seen a rapid increase in incidence in the United States. Racial and ethnic differences in HCC incidence have been observed, with Latinos showing the greatest increase over the past four decades, highlighting a concerning health disparity. The goal of the present study was to compare the clinical features at the time of diagnosis of HCC in Latino and Caucasian patients.

Material and methodsWe retrospectively screened a total of 556 charts of Latino and Caucasian patients with HCC.

ResultsThe mean age of HCC diagnosis was not significantly different between Latinos and Caucasians, but Latinos presented with higher body mass index (BMI). Rates of hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia were similar in the two groups. The most common etiology of liver disease was alcohol drinking in Latinos, and chronic hepatitis C in Caucasian patients. Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) was the associated diagnosis in 8.6% of Latinos and 4.7% of Caucasians. Interestingly, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels at time of diagnosis were higher in Latino patients compared to Caucasians, but this difference was evident only in male patients. Multifocal HCC was slightly more frequent in Latinos, but the two groups had similar cancerous vascular invasion. Latino patients also presented with higher rates of both ascites and hepatic encephalopathy.

ConclusionLatino and Caucasian patients with HCC present with a different profile of etiologies, but cancer features appear to be more severe in Latinos.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common cancer in men and seventh most common cancer in women, and the second leading cause of cancer related deaths.1,2 While the high prevalence observed in Asia and Africa is due to the high incidence of hepatitis viruses, the rising incidence of HCC in the United States is likely due to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)3 as well as the high prevalence of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The incidence of HCC has more than tripled in the United States since the early 1980s4 and, of all types of cancers, has shown the greatest increase in mortality.4

Ethnic differences in the incidence of HCC have been described, with higher rates noted in Asians, Latinos and African Americans.5-8 In the United States, Latinos have experienced the largest increase in HCC incidence over the past 40 years.2,9 Recent analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology End Result (SEER) found the incidence rates in Latinos to be 2.5 times higher as compared to White Caucasians.6 These rates are expected to further increase, as Latino Americans are the most rapidly growing ethnic minority in the United States. Recent immigration patterns indicate Latinos will comprise up to 30% of the total US population by the year 2050.10,11 Furthermore, recent studies describe Latinos developing HCC at younger ages and having a greater prevalence of metabolic risk factors when compared to non-Latino Whites.7,12 The incidence of HCC in Latino men has doubled over the past 15 years making the overall rate double that of non-Latino men.13 Mortality rates for Latino patients are higher than their Asian and White counterparts despite a higher incidence of liver cancer in Asian populations.5,14 Little is known about the presentation and features of HCC in Latinos compared to non-Latinos despite the staggeringly high rates and mortality due to HCC in the Latino population.

Diabetes mellitus (DM), which is thought to be one risk factor leading to development of HCC, has a high prevalence rate in the Latino population.15 Setiawan, et al. studied a multiethnic cohort and identified Latinos as the ethnic group at highest risk for developing HCC and DM was identified as a risk factor.16 The differences in incidence as well as overall survival rate may be secondary to the underlying etiology of HCC. Asians typically have higher rates of hepatitis B virus (HBV), while Latinos and Blacks have higher rates of HCV, NAFLD, and alcoholic liver disease.17 Venepalli, et al. found Latino patients with HCC have a higher incidence of modifiable risk factors, high rates of NASH, and shorter overall survival than Caucasian and African American patients.11 Latinos have the greatest prevalence of NAFLD18 and higher rates of obesity.19,20 It is likely other ethnic-specific differences and genetic factors contribute to the progression of HCC even when the etiology of the disease is the same.16

Therefore, identifying the reversible or modifiable risk factors associated with HCC in Latinos is critical to begin to bridge the racial disparity gap of HCC. The goal of our study was to determine clinical features of HCC at the time of diagnosis in Latino patients as compared to nonLatino Whites. A better understanding of ethnic-specific risk factors will improve screening and surveillance efforts in this population, as well as possibly identify ethnic-specific treatments which will assist in decreasing the incidence of this deadly cancer in a vulnerable population.

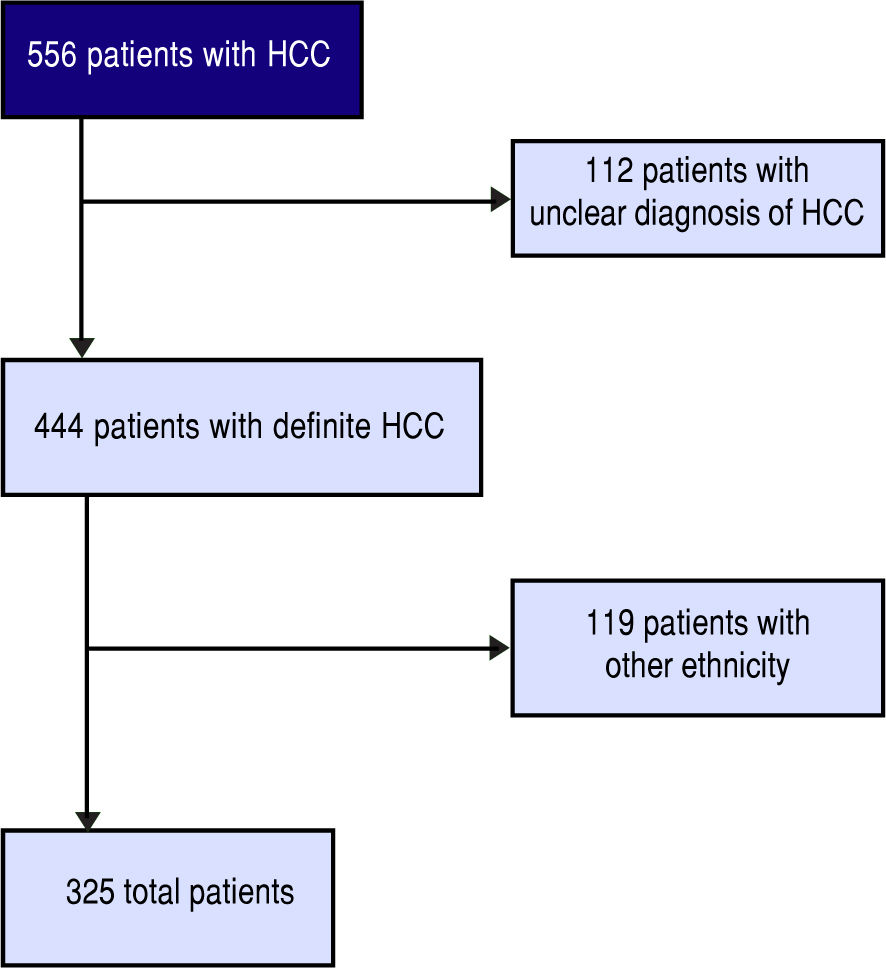

Material and MethodsStudy populationWe performed a retrospective chart review of Latino and non-Latino White patients. All patients were identified using electronic medical records from the University of California Davis Medical Center in Sacramento, California between 01/01/2008-12/31/2014 using the ICD-9 code of HCC. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, Davis Medical Center in Sacramento, CA (IRB # 391877). Of note, it has been estimated that 83% of Latinos living in the Sacramento area are Mexican Americans.20 We initially identified a total of 556 Caucasian and Latino subjects with a diagnosis of HCC. Subjects were excluded from data analysis for the following reasons: HCC diagnosis was uncertain or not confirmed (n = 103), HCC diagnosis was, upon further review, not entered into the electronic medical record (n = 9), ethnicity was not properly described or was other than Latino or White (n = 119) (Figure 1). The final analysis included a total of 325 patients with a diagnosis of HCC that were either Latino (n = 70) or Caucasian (n = 255).

Data CollectionWe used the demographic section of the electronic medical record to identify our research population. We collected demographic information on all of our patients: ethnicity (quantified as Latino or Not Latino), race (categories included American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Black/African American, White, more than 1 race, Unknown, Other), confirmed diagnosis of HCC (yes or no), age at diagnosis, and Body Mass Index (BMI) at diagnosis. We collected clinical and laboratory data at time of HCC diagnosis, including: presence and etiology of cirrhosis as determined by imaging via ultrasound, CT scan or MRI scan, history of hypertension, diabetes, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level, high-density Lipoprotein (HDL), triglycerides, creatinine, albumin, alanine transaminase (ALT), total bilirubin, presence of ascites and/or hepatic encephalopathy, International Normalized Ratio (INR), and from that, calculated Child-Pugh and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores. We also collected data related to HCC features, including which imaging modality was used to identify the HCC lesion, if multifocal involvement was present, and Milan Criteria and Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) Score.

Statistical AnalysesStatistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics, version 24 (USA) and R statistical software, version 3.3.3 (Austria). For continuous data, differences between groups were assessed by two-tailed Student’s T-test. For categorical data, differences were assessed by Fisher’s exact test. Spearman’s correlation was used to determine correlations among continuous variables. Data are presented as mean ± SD. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

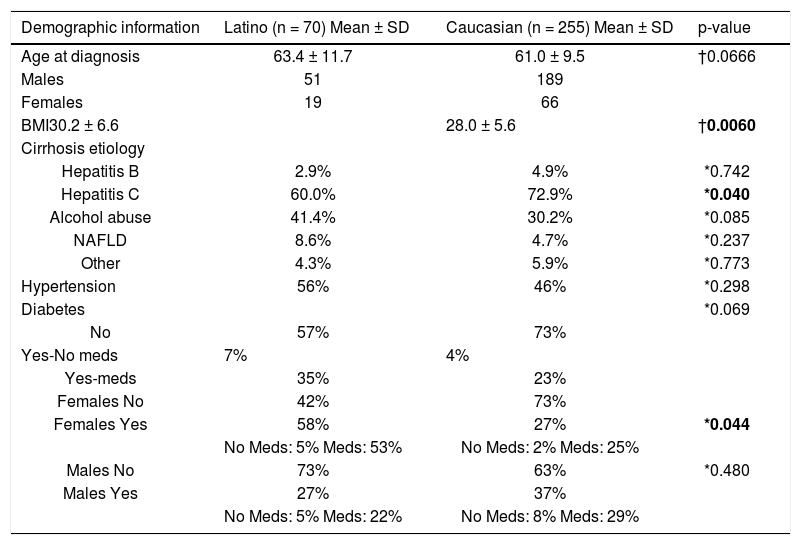

ResultsThe mean age at diagnosis of HCC for Latino patients was 63.4 ± 11.7 years and 61 ± 9.5 years for Caucasian patients (NS). BMI at presentation was significantly higher in Latino patients than Caucasian patients, 30.2 ± 6.6 vs. 28.0 ± 5.6 respectively. In both ethnicities, hepatitis C was the most frequent condition associated with cirrhosis, with a higher prevalence in Caucasians compared to Latinos. The second most common etiology of liver cirrhosis was alcohol abuse in both ethnicities (Table 1).

Demographic information.

| Demographic information | Latino (n = 70) Mean ± SD | Caucasian (n = 255) Mean ± SD | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | 63.4 ± 11.7 | 61.0 ± 9.5 | †0.0666 |

| Males | 51 | 189 | |

| Females | 19 | 66 | |

| BMI30.2 ± 6.6 | 28.0 ± 5.6 | †0.0060 | |

| Cirrhosis etiology | |||

| Hepatitis B | 2.9% | 4.9% | *0.742 |

| Hepatitis C | 60.0% | 72.9% | *0.040 |

| Alcohol abuse | 41.4% | 30.2% | *0.085 |

| NAFLD | 8.6% | 4.7% | *0.237 |

| Other | 4.3% | 5.9% | *0.773 |

| Hypertension | 56% | 46% | *0.298 |

| Diabetes | *0.069 | ||

| No | 57% | 73% | |

| Yes-No meds | 7% | 4% | |

| Yes-meds | 35% | 23% | |

| Females No | 42% | 73% | |

| Females Yes | 58% | 27% | *0.044 |

| No Meds: 5% Meds: 53% | No Meds: 2% Meds: 25% | ||

| Males No | 73% | 63% | *0.480 |

| Males Yes | 27% | 37% | |

| No Meds: 5% Meds: 22% | No Meds: 8% Meds: 29% |

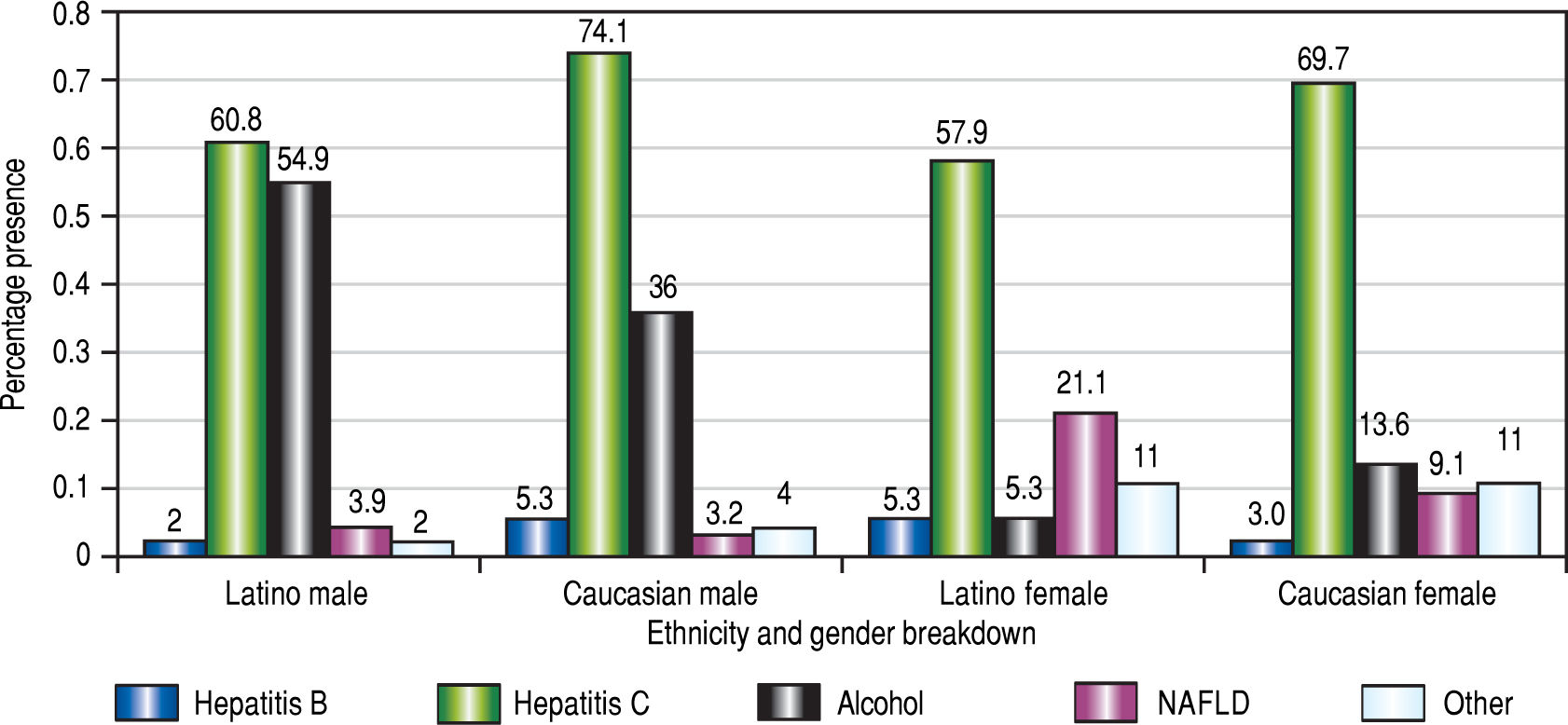

Among Latino men, alcohol consumption caused a significantly higher proportion of cirrhosis (54.9% in Latinos vs. 36.0% in Caucasians, p = 0.021), whereas hepatitis C was the most frequent etiology of cirrhosis among Caucasian males, (60.8% in Latino males vs. 74.1% in Caucasian males, p = 0.048). Comparing Latino males and females, men had a significantly higher proportion of cirrhosis from alcohol (54.9% in Latino males vs. 5.3% in Latino females, p < 0.001), whereas in Latino women, cirrhosis was due largely to NAFLD (3.9% in Latino males vs. 21.1% in Latino females, p = 0.042). Similarly, when comparing Caucasian males and females, men had a significantly higher proportion of cirrhosis from alcohol as compared to females (36% in Caucasian males and 13.6% in Caucasian females, p < 0.001) (Figure 2).

Cirrhosis etiology by ethnicity and sex. Cirrhosis etiology due to alcohol consumption is significantly higher in Latino males than in either Caucasian males or Latino females; a significantly higher proportion of Latino females had cirrhosis from NAFLD, compared to Latino males; significantly more Caucasian males had HCV as the etiology of their cirrhosis compared to Latino males; significantly more Caucasian males had alcoholic cirrhosis compared to Caucasian females.

Latinos had higher rates of hypertension and diabetes compared to Caucasians, but the difference was not statistically significant. However, Latino females had significantly higher rates of diabetes compared to Caucasian females (58% vs. 27% respectively, p = 0.044) (Table 1).

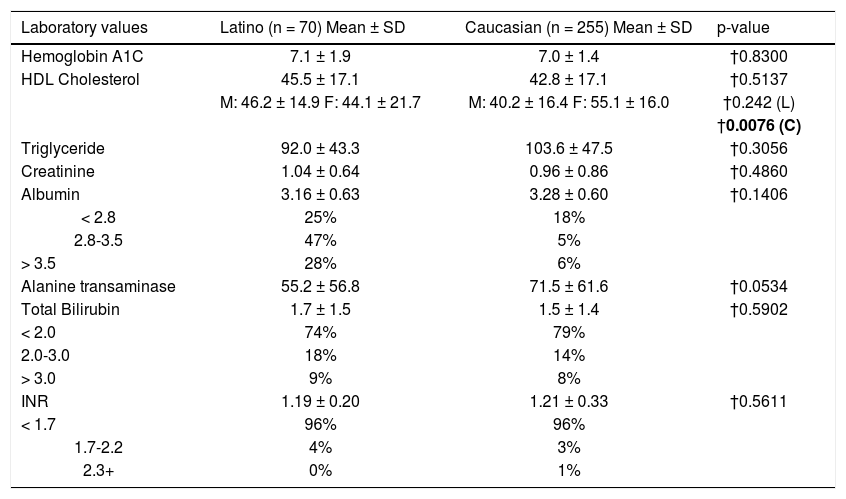

Hemoglobin A1c, triglycerides and creatinine were not significantly different between ethnicities or sexes. Caucasian females did have significantly higher HDL than their male counterparts, (55.1 ± 16.0 vs. 40.2 ± 16.4, p = 0.0076). Albumin, ALT, total bilirubin and INR were not significantly different between ethnic groups. Most patients had an INR < 1.7, an albumin of between 2.8-2.5 and a total bilirubin < 2.0 (Table 2).

Various serum test values, with standard deviations and p-values.

| Laboratory values | Latino (n = 70) Mean ± SD | Caucasian (n = 255) Mean ± SD | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin A1C | 7.1 ± 1.9 | 7.0 ± 1.4 | †0.8300 |

| HDL Cholesterol | 45.5 ± 17.1 | 42.8 ± 17.1 | †0.5137 |

| M: 46.2 ± 14.9 F: 44.1 ± 21.7 | M: 40.2 ± 16.4 F: 55.1 ± 16.0 | †0.242 (L) | |

| †0.0076 (C) | |||

| Triglyceride | 92.0 ± 43.3 | 103.6 ± 47.5 | †0.3056 |

| Creatinine | 1.04 ± 0.64 | 0.96 ± 0.86 | †0.4860 |

| Albumin | 3.16 ± 0.63 | 3.28 ± 0.60 | †0.1406 |

| < 2.8 | 25% | 18% | |

| 2.8-3.5 | 47% | 5% | |

| > 3.5 | 28% | 6% | |

| Alanine transaminase | 55.2 ± 56.8 | 71.5 ± 61.6 | †0.0534 |

| Total Bilirubin | 1.7 ± 1.5 | 1.5 ± 1.4 | †0.5902 |

| < 2.0 | 74% | 79% | |

| 2.0-3.0 | 18% | 14% | |

| > 3.0 | 9% | 8% | |

| INR | 1.19 ± 0.20 | 1.21 ± 0.33 | †0.5611 |

| < 1.7 | 96% | 96% | |

| 1.7-2.2 | 4% | 3% | |

| 2.3+ | 0% | 1% |

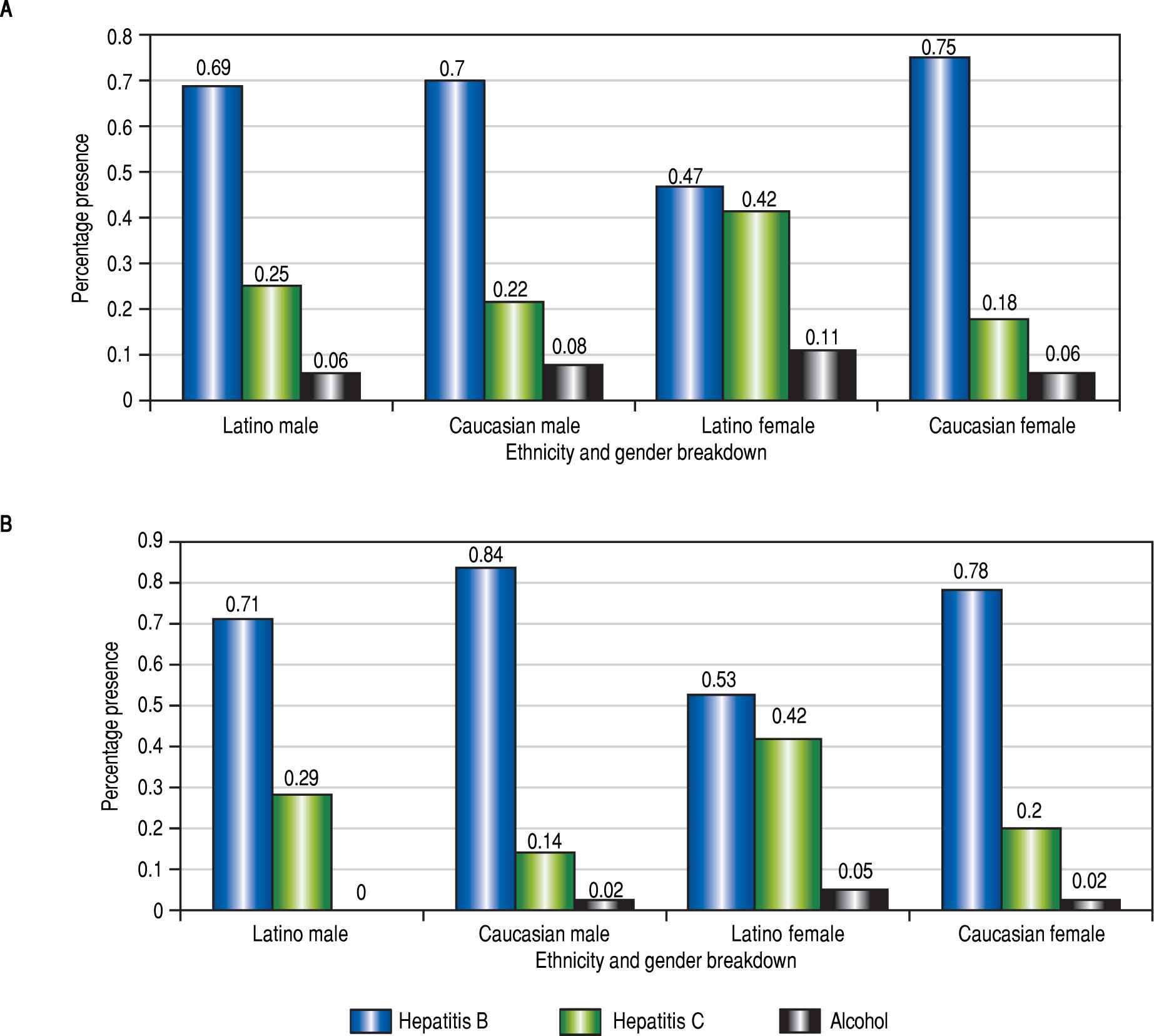

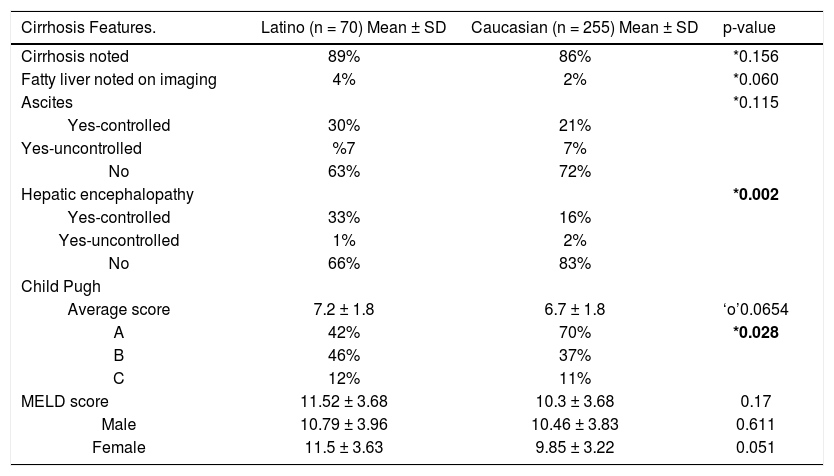

When evaluating features of liver disease, cirrhosis was present in the majority of patients, both Latinos and Caucasians. Fatty liver was noted in few patients in our population via imaging studies (ultrasound, CT scan, MRI). For ascites and hepatic encephalopathy, it was first determined if each manifestation of cirrhosis was present, and if so, if the symptoms were controlled with medical therapy or not. The majority of patients did not have ascites, and of those that did have ascites, it was largely controlled by the use of diuretics. Only a small portion of patients, both Latinos and Caucasians, had uncontrolled ascites when on diuretics and Latino females had medication-controlled ascites more frequently than Caucasian females (Figure 3). Most patients did not have hepatic encephalopathy, but a significantly higher proportion of Latinos had medication-controlled hepatic encephalopathy (Fig ure 3). Most Caucasian patients had a Child-Pugh Class score of A, while most Latinos had a score of B (Table 3). MELD scores were not statistically different between sexes or ethnicities, although the largest differences were observed between Latino and Caucasian females (Table 3).

Complications of cirrhosis: absence or presence of ascites and hepatic encephalopathy. A. Proportion of patients with ascites. Rates of ascites were not statistically different between the two ethnic groups. B. Proportion of patients with hepatic encephalopathy, A significantly higher proportion of Latino males had hepatic encephalopathy compared to Caucasian males; comparing females, rates of hepatic encephalopathy were not different.

Cirrhosis Features

| Cirrhosis Features. | Latino (n = 70) Mean ± SD | Caucasian (n = 255) Mean ± SD | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cirrhosis noted | 89% | 86% | *0.156 |

| Fatty liver noted on imaging | 4% | 2% | *0.060 |

| Ascites | *0.115 | ||

| Yes-controlled | 30% | 21% | |

| Yes-uncontrolled | %7 | 7% | |

| No | 63% | 72% | |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | *0.002 | ||

| Yes-controlled | 33% | 16% | |

| Yes-uncontrolled | 1% | 2% | |

| No | 66% | 83% | |

| Child Pugh | |||

| Average score | 7.2 ± 1.8 | 6.7 ± 1.8 | ‘o’0.0654 |

| A | 42% | 70% | *0.028 |

| B | 46% | 37% | |

| C | 12% | 11% | |

| MELD score | 11.52 ± 3.68 | 10.3 ± 3.68 | 0.17 |

| Male | 10.79 ± 3.96 | 10.46 ± 3.83 | 0.611 |

| Female | 11.5 ± 3.63 | 9.85 ± 3.22 | 0.051 |

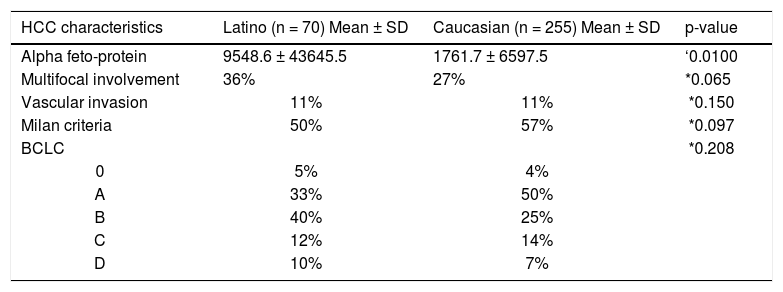

When studying the features of HCC lesions, Latino patients had a significantly higher mean AFP value, but the result was evident only when comparing Latino and Caucasian men. In Latino men, AFP was on average 7 times higher compared to their Caucasian counterpart (p = 0.0073). Multifocal involvement was more frequent in Latinos, but the difference was not statistically significant. Both ethnic groups had similar rates of cancerous vascular invasion. The BCLC scores between the two ethnicities were not statistically different, although Latinos were most commonly in the B category, while Caucasian patients were most often in the A category (Table 4).

HCC characteristics

| HCC characteristics | Latino (n = 70) Mean ± SD | Caucasian (n = 255) Mean ± SD | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha feto-protein | 9548.6 ± 43645.5 | 1761.7 ± 6597.5 | ‘0.0100 |

| Multifocal involvement | 36% | 27% | *0.065 |

| Vascular invasion | 11% | 11% | *0.150 |

| Milan criteria | 50% | 57% | *0.097 |

| BCLC | *0.208 | ||

| 0 | 5% | 4% | |

| A | 33% | 50% | |

| B | 40% | 25% | |

| C | 12% | 14% | |

| D | 10% | 7% |

HCC is the most common type of liver cancer and has an 84% mortality rate 5 years after diagnosis. Ethnic disparities related to HCC presentation and severity have attracted much attention in recent years.21 Mortality rates from liver disease and its complications are almost 50% higher in Latino patients compared to their non-Latino counterparts, and HCC is the sixth most common cause of death in Latinos, whereas it is not in the top ten causes of death in Black or Caucasian populations.22,23 More research is being conducted in an effort to clarify the factors contributing to this phenomenon and to reduce ethnic-driven health disparities. Growing evidence indicates both obesity and diabetes are associated with higher rates of developing HCC. While non-Latino diabetics were at higher risk for development of HCC than non-diabetics, Latinos had the strongest association between diabetes and development of HCC.16

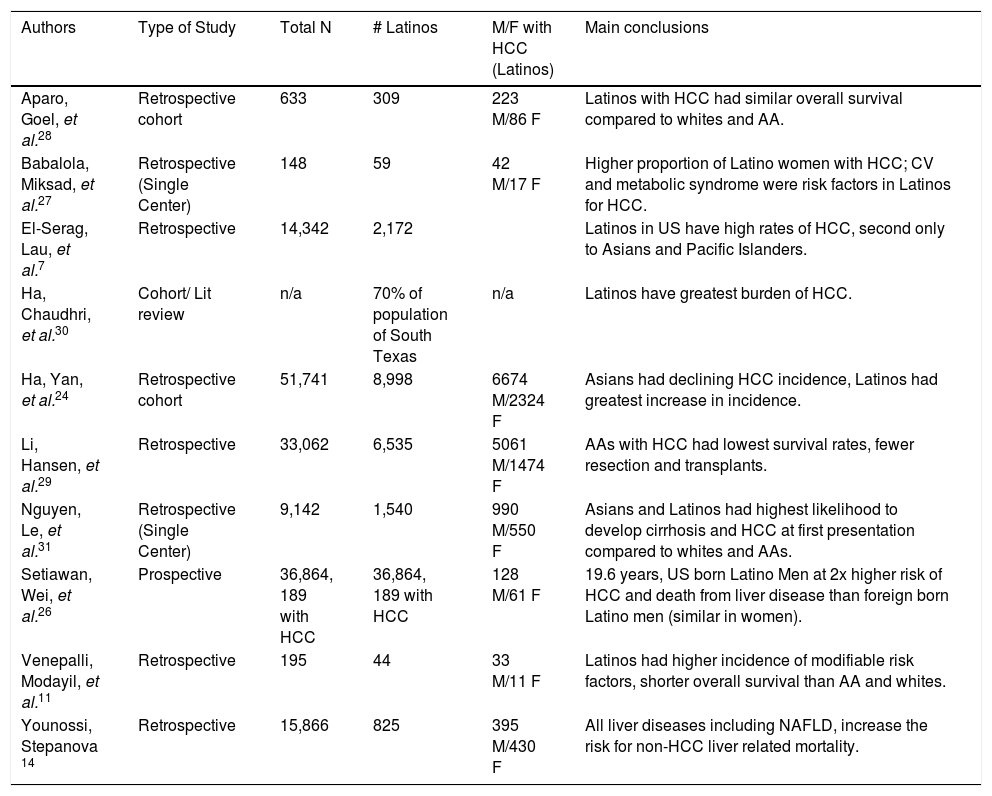

Findings from this single-center retrospective cohort study build on the current literature (summerized in table 5) showing that Latinos present with HCC at more advanced stages than their Caucasian counterparts. It is currently unclear as to why this is, with a vast variation of hypotheses, from socioeconomic factors prohibiting medical care to increased risk of metabolic syndrome and associated diseases leading to higher risk of development of HCC to cultural factors of waiting longer to visit a health care provider. We found Latinos had higher rates of decompensated liver disease, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy, as well as higher Child-Pugh scores. Additionally, Latino patients had higher rates of symptoms of decompensated liver disease that were controlled with medical therapy vs. their Caucasian counterparts. Ha, et al. demonstrated that although Asians had the highest incidence of HCC, they experienced a decrease in overall incidence over recent years, while Latinos experienced the greatest increase in HCC incidence.24 AFP levels were also higher in Latinos, particularly in Latino men. This is consistent with previous studies showing Latino ethnicity was an independent risk factor for HCC-related death, with a worse 5-year survival rate when compared to White and Asian counterparts.5,14 Additionally, national data indicate a higher prevalence, more advanced features of chronic liver disease, and higher liver related mortality in Latino patients.11,23 Unfortunately, there are scant data on the features that contribute to or predict different outcomes based on ethnicity.

Literature review.

| Authors | Type of Study | Total N | # Latinos | M/F with HCC (Latinos) | Main conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aparo, Goel, et al.28 | Retrospective cohort | 633 | 309 | 223 M/86 F | Latinos with HCC had similar overall survival compared to whites and AA. |

| Babalola, Miksad, et al.27 | Retrospective (Single Center) | 148 | 59 | 42 M/17 F | Higher proportion of Latino women with HCC; CV and metabolic syndrome were risk factors in Latinos for HCC. |

| El-Serag, Lau, et al.7 | Retrospective | 14,342 | 2,172 | Latinos in US have high rates of HCC, second only to Asians and Pacific Islanders. | |

| Ha, Chaudhri, et al.30 | Cohort/ Lit review | n/a | 70% of population of South Texas | n/a | Latinos have greatest burden of HCC. |

| Ha, Yan, et al.24 | Retrospective cohort | 51,741 | 8,998 | 6674 M/2324 F | Asians had declining HCC incidence, Latinos had greatest increase in incidence. |

| Li, Hansen, et al.29 | Retrospective | 33,062 | 6,535 | 5061 M/1474 F | AAs with HCC had lowest survival rates, fewer resection and transplants. |

| Nguyen, Le, et al.31 | Retrospective (Single Center) | 9,142 | 1,540 | 990 M/550 F | Asians and Latinos had highest likelihood to develop cirrhosis and HCC at first presentation compared to whites and AAs. |

| Setiawan, Wei, et al.26 | Prospective | 36,864, 189 with HCC | 36,864, 189 with HCC | 128 M/61 F | 19.6 years, US born Latino Men at 2x higher risk of HCC and death from liver disease than foreign born Latino men (similar in women). |

| Venepalli, Modayil, et al.11 | Retrospective | 195 | 44 | 33 M/11 F | Latinos had higher incidence of modifiable risk factors, shorter overall survival than AA and whites. |

| Younossi, Stepanova 14 | Retrospective | 15,866 | 825 | 395 M/430 F | All liver diseases including NAFLD, increase the risk for non-HCC liver related mortality. |

One of the studies found in the literature review collected similar data to ours, including the features of Latino patients at time of presentation of HCC diagnosis. Venepalli, et al. demonstrated that Latinos had significantly higher rates of modifiable risk factors of liver disease, higher prevalence of NASH and End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD), as well as more advanced liver disease, with higher rates of portal hypertension, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy and higher MELD scores.11 Our study confirms many of these findings. Latino women were at significantly higher risk of having diabetes. Latinos, and particularly women, had almost twice the rates of NASH related liver disease compared to patients of other races. Younossi, et al. also showed that Latino ethnicity was an independent risk factor for HCC-related mortality, demonstrating a 5-fold higher risk of HCC mortality.14 Prior studies have suggested there may be a higher rate of inflammation and aminotransferase derangements in Latino patients with NASH than in other ethnic groups, given differing metabolic and socioeconomic factors between Latino vs. non-Latino whites.25 Increasing evidence demonstrates that diabetes and obesity are independetly associated with increased risk of development of HCC. Latino patients have a strong association between these diseases and HCC development as compared to non-Hispanics.26 Babalola, et al. confirmed that Latino patients had higher rates of metabolic syndrome, but unlike our study, showed that they also had higher rates of hepatitis C and were more likely to be female than their non-Latino cohort.27 These differences may have been due to the fact that their cohort was taken from a teaching hospital in Boston, where the majority of their Latino population is Puerto Rican, whereas in our study the majority of our Latino patients are Mexican. Setiawan’s longitudinal study also supported the association between metabolic syndrome and HCC development, showing diabetic Latino patients had a 3.3x higher risk of HCC development as compared to non-diabetic Latinos, with a 2.2x higher risk of HCC in diabetic non-Latinos as compared to non-diabetic counterparts.16 Association of metabolic syndrome and its related diseases with progression to chronic liver disease in Latinos is of great importance, as interventions leading to decreasing these risk factors could possibly significantly decrease the incidence of HCC in Latinos, if not all ethnic groups. Furthermore, targeted screening of Latinos with these risk factors could lead to earlier diagnosis and increased survival rates. While some of the studies that have been performed to date confirm several of our results, our study is unique, looking particularly at Latino patients and their characteristics at presentation, which has largely not been reported thus far.

One of the major limitations of our study is the relatively small sample size, in particular the small number of Latino patients. Additionally, our retrospective cohort design causes biases that are associated with this type of study, for example such as the inability to contact patients to obtain socio-economic data. Lack of social support and access of needed care may influence the time to diagnosis of some of our patients. Furthermore, a single-center study in Northern California may not be applicable to all Latino populations. Nevertheless, we believe our study provides a comprehensive analysis of disparities that exist between Latinos and Caucasians with HCC, particularly alcohol comsumption as well as various features of HCC that are more prevalant in Latino patients, such as NAFLD in women, as well as Hepatic encephalopathy.

In conclusion, our study provides important data on clinical features of presentation of Latinos with HCC. Latino patients present with higher rates of comorbidities and more advanced liver disease as compared to their White counterparts, often leading to increased mortality from HCC in this ethnic group. This is likely explained by a combination of metabolic risk factors, higher rates of NASH cirrhosis and alcoholic cirrhosis as well as more aggressive progression of cirrhosis leading to malignancy and death. We further identified that, at least in men, AFP levels are higher in Latino patients, although the significance of this is unclear at this time, given the level is more elevated in advanced disease, regardless of ethicity. Further prospective studies are needed to collect clinical, socio-economic and genetic information on these patients to determine their link to HCC severity and reduce the health disparity. It is the hope that with more advanced and directed screening of these various risk factors, and determination of which individuals might be at higher risk of development of HCC, we can target these patients more carefully and prevent development of this deadly cancer.

Abbreviations- •

ALT:alanine transaminase.

- •

AFP: alpha-fetoprotein.

- •

BCLC: Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer.

- •

BMI: body mass index.

- •

DM: diabetes mellitus.

- •

ESRD: end stage renal disease.

- •

HBV: hepatitis B virus.

- •

HCV: hepatitis C virus.

- •

HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma.

- •

HDL: high-density lipoprotein.

- •

INR: international normalized ratio.

- •

MELD: model for end-stage liver disease.

- •

NAFLD: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

- •

NASH: non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

- •

SEER: surveillance, epidemiology end result.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

DisclosuresThe project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through grant number UL1 TR001860. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.