Introduction and aim. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a global medical problem. HLA -DRB1 alleles have an important role in immune response against HCV. The aim of this study is to clarify the contribution of HLA -DRB1 alleles in HCV susceptibility in a multicentre family-based study.

Material and methods. A total of 162 Egyptian families were recruited in this study with a total of 951 individuals (255 with chronic hepatitis C (CHC), 588 persons in the control group(-ve household contact to HCV) and 108 persons who spontaneously cleared the virus (SVC). All subjects were genotyped for HLA -DRB1 alleles by SSP-PCR and sequence based typing (SBT) methods.

Results. The carriage of alleles 3:01:01 and 13:01:01 were highly significant in CHC when compared to that of control and SVC groups [OR of 3 family = 5.1289, PC (Bonferroni correction ) = 0.0002 and 5.9847, PC = 0.0001 and OR of 13 family = 4.6860, PC = 0.0002 and OR = 6.5987, PC = 0.0001 respectively]. While DRB1*040501, DRB1*040101, DRB1*7:01:01 and DRB1*110101 alleles were more frequent in SVC group than CHC patients (OR = 0.4052, PC = 0.03, OR: OR = 0.0916,PC = 0.0006, OR = 0.1833,PC = 0.0006 and OR = 0.4061, PC = 0.0001 respectively).

Conclusions. It was concluded that among the Egyptian families, HLA-DRB1*030101, and DRB1*130101 alleles associated with the risk of progression to CHC infection, while DRB1*040101, DRB1*040501, DRB1*7:01:01and DRB1*110101 act as protective alleles against HCV infection.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a global health problem.1 In 2013 HCV was infecting approximately 2%-3% of the world’s population, with additional 3-4 millions are infected annually.2 Although acute hepatitis C is asymptomatic, HCV persists in about 70%-85% of cases.3 The role of nonsexual HCV interfamilial transmission is controversial. The prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies among household contacts of infected patient was found to be 13.7% in Egypt4 HCV is slowly progressive disease, as cirrhosis will develop in about 20%-30% of patients within 20 years and 1%-4% of them are at high risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).5 The natural history of HCV infection is determined by a complex interaction between host genetic, immunological and viral factors.6

Although HCV elicits innate immune responses early after infection the virus can overcome the immunity and persist. Viral clearance occurs only in the presence of antiviral CD4+ and CD8 + T cell responses.7

The class I and class II human leukocyte antigens (HLA) are ideal candidate genes to study associations between HCV infection and outcomes.8 Specific HLA alleles have been shown to influence the outcome of the HCV infection.5

Class II is composed of three major genes DR, DQ, and DP. HLA-DR is composed of multiple genes and DRB1 is the most polymorphic and important one which gives variation in immune response.8 A recent study from Egypt reported that the clearance of HCV was associated with DQB1 03:01:01:01 allele while the chronicity of HCV infection was associated with the risk allele: DQB1*02:01:01.9 Several studies reported that HLA-DRB1 alleles may play a critical role in the susceptibility to or clearance from HCV infection and also may determine the response to antiviral drugs.8,10,11

The responsibility of the HLA-DRB1 alleles for the susceptibility to HCV infection is highly variable from one population to another.11

We aimed in this study to investigate the role of HLA-DRBlin HCV infection in large family based study community to avoid any concomitant population stratification or type I error.

Material and MethodsSubjectsThis multicenter study was carried out in the Molecular Genetic Unit in Endemic Hepatogastroenterology and Infectious Diseases (MGUHID), Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University. We investigated Egyptian HCV patients and their families or close household contacts from different Egyptian population representing [Upper Egypt and lower Egypt (including East and West Delta)] Mainly from Dakahlia, Cairo & Assuit governorates between 2011 and 2015. We selected the families on the bases of including at least one positive HCV member (index), one positive for HCV markers and one family member negative for HCV infection or liver complications and disorders. According to these criteria 162 Egyptian families were recruited in this study with a total of 951 individuals (255 infected participants with chronic hepatitis C (CHC), 588 controls (a household contact negative to HCV) and108participants who spontaneously cleared the virus (SVC): i.e with positive Anti-HCV but negative PCR HCV RNA in 2 successive samples at least 6 months apart with no prior history of antiviral therapy. The index cases in the family were selected with inclusion criteria of 1-HCV positive by PCR RNA > 6 months, 2-Adults (above 18 years) of both sexes 3-Any stage of HCV related liver diseases, while exclusion criteria of the index cases were:

- •

Patients co-infected with HIV or HBV (HBV core antibodies).

- •

Patient with anti-HCV antibodies positive and no detectable PCR-HCV in the serum, also autoimmune hepatitis, HCC and metabolic liver diseases were excluded.

Healthy control household contacts were included in this study with inclusion criteria of 1-Age > 18 years of both sex, 2-first and second degree consanguinity to the index case living and sharing usual life activity with index case and having at least 15 years of exposure to the index case. 3-serological evidence of HCV, HBV, HCC, and history of liver diseases were excluded. Each participant was subjected to routine clinical and laboratory investigations by one staff clinician in addition to molecular diagnosis and PCR HCV to confirm HCV infection. All the studied cases were subjected to clinical examinations and routine laboratory investigations (complete blood picture, liver function tests).

This study was carried out in accordance with the most recent declaration of Helsinki, and each participant signed a written informed consent before participating in the study. The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of the Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University, Egypt.

Methods- •

HCV-PCR. Viral RNA was extracted from serum using Qiagen RNA extraction kit (QIA amp® DNA Blood kit (QIAGEN GmbH; Hilden’s, Germany) according to manufacturer instructions. Extracted HCV RNA samples were quantitatively by real time PCR (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA, USA, 7,500 real time PCR system) that determine the viral load of the samples. Sero-negative HCV-Ab were pooled and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 60 min. Supernatant was discarded and the pellet was resuspended in 150 jL of supernatant and extracted for viral RNA.

- •

DNA extraction. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood cells using a DNA extraction kit (QIAmp DNA Mini kit; Qiagen, Hilden’s, Germany)according to manufacturer instructions. Extracted DNA were assessed by using NanoDropTM (NanoDrop™2000/2000c spectrophotometer, Thermo Scientific, USA)

- •

HLA-DRB1 typing. Low and high resolution typing combine in this complete, two-step system for HLA-DRB1 typing research. The 9 ready-reaction PCR mixes provide high specificity amplification using allele group-specific primers for exon 2 of HLA-DRB1. The PCR products are subsequently sequenced to generate high-resolution allele assignments.

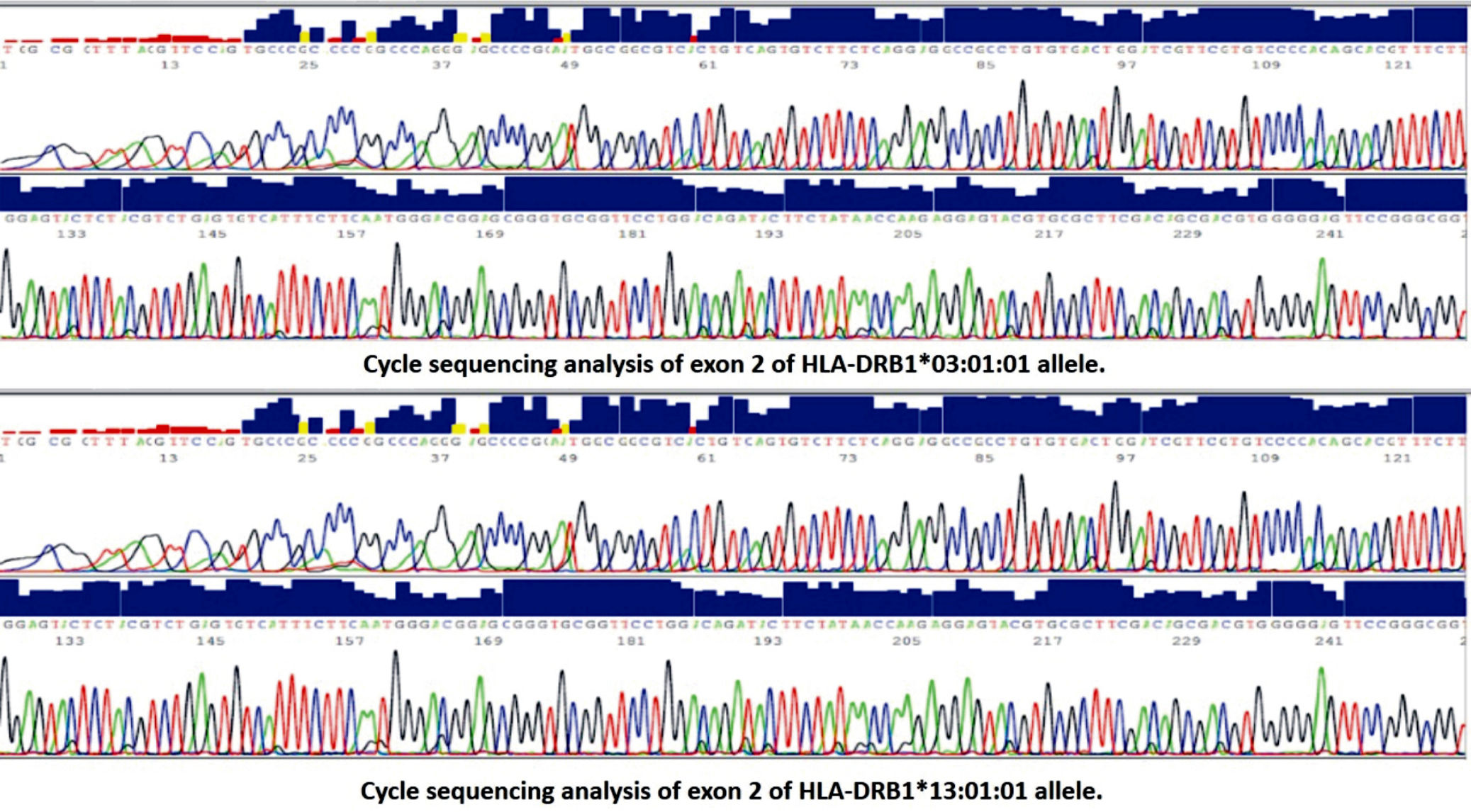

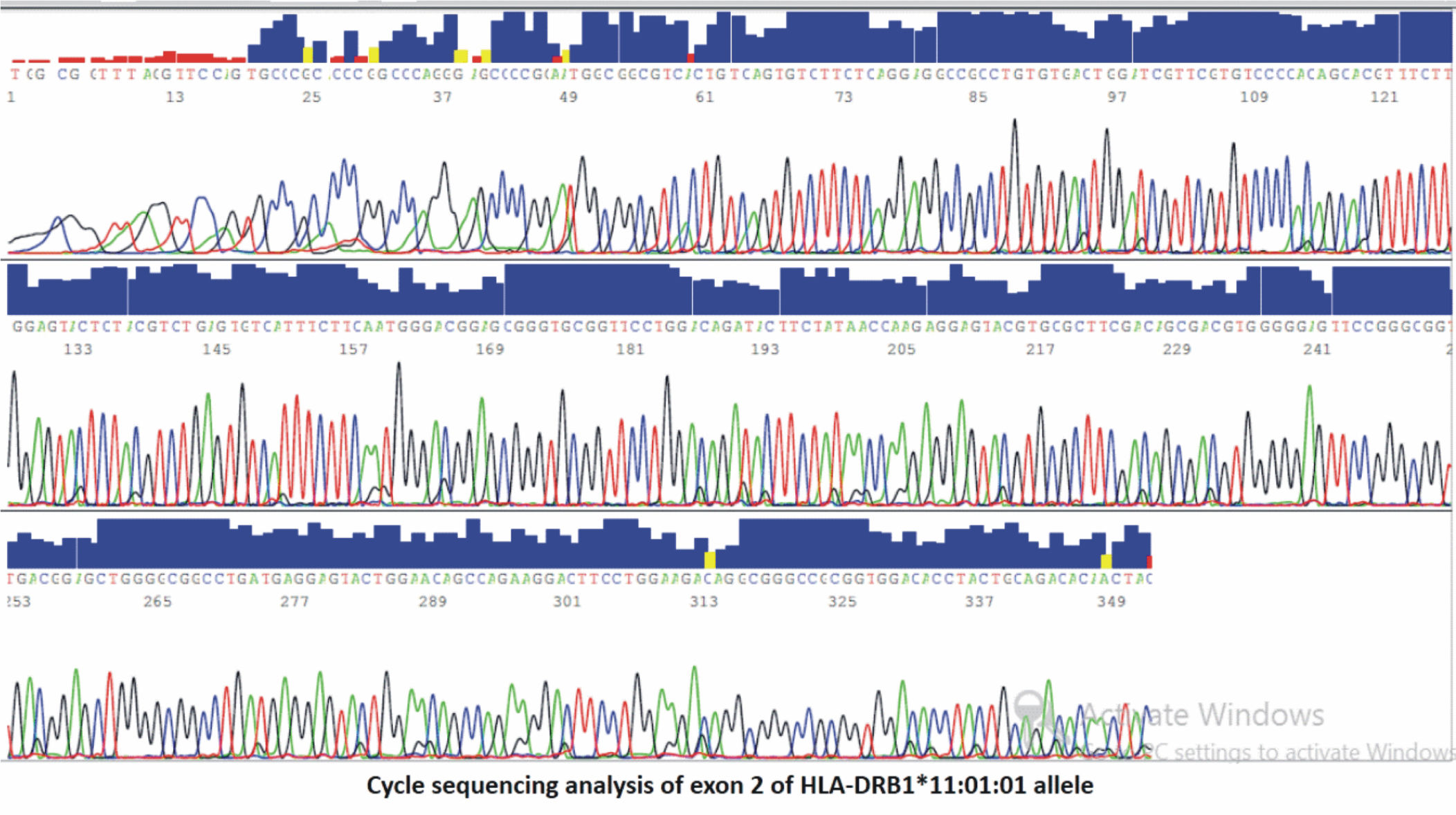

The second exon of HLA-DRB1 gene was typed using sequence based typing (SBT). For HLA-DRB1exon 2 alleles sequencing, amplification was first done using specific sequence primer pair (Qiagen kit). The PCR reaction was done using a thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, 2720). A cycle sequence was performed for the purified PCR product in the forward direction by the forward primer using Big Dye TM terminator Cycle sequencing kits (versions 3.0) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Sequenced products were then separated by capillary electrophoresis using an Applied Biosystems 310 Genetic Analyzer. Sequences were analyzed with dedicated software.

- •

HLA genotyping analysis. This consensus sequences were compared against the appropriate library of HLA alleles (www.ebi.ac.uk/ipd/imgt/hla/blast.html) and (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)) to obtain the results of specific allele sequence.

Data were computed and statistically analyzed using SPSS software program. (IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). For comparison of qualitative variables (presented as frequencies and percentages) %2 of Fisher Exact test were used. Hardy Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was assessed in each group separately using %2 tests. The allele carriage is defined as the number of individuals carrying at least one copy of a specific allele. Allelic frequencies are defined as the number of occurrences of the test allele divided by the total number of alleles in the group. Odds ratio at 95% confidence interval (CI) of specific allele carriage was calculated compared with the non-carriage of target allele using Med Calc software(Med Calc statistical software version 16.4.3. Med Calc (software bvba, Ostend,Belgium; https://www.medcalc.org; 2016). The difference was considered significant if P < 0.05. OR and confidence interval was calculated using two by two contingency table by comparing the allele carriage of at least one copy of this allele in different groups. If OR and 95 %CI is greater than 1. It mean this allele is a risk one. The allele is considered as protective allele if OR and 95% CI is less than one. The p value statistic of OR was adjusted using Bonferroni formula (PC corrected) The Bonferroni corrected-p value is an adjustment made to P values when several dependent or independent statistical tests are being performed simultaneously on a single data set.12

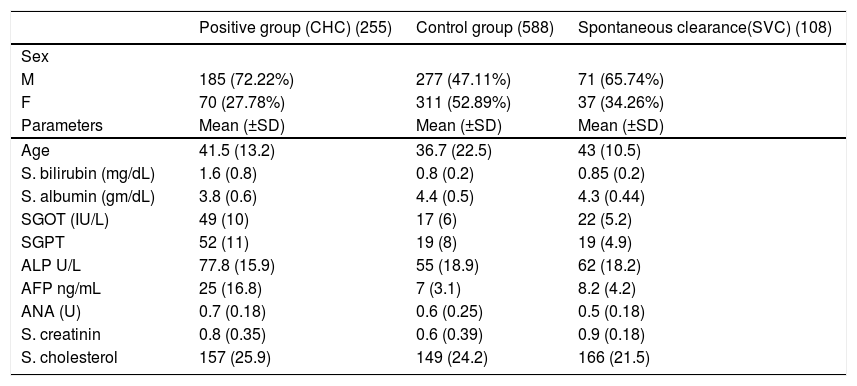

ResultsThe laboratory charateristics of the studied groups are shown in table 1.

Clinical & laboratory characteristics of studied groups.

| Positive group (CHC) (255) | Control group (588) | Spontaneous clearance(SVC) (108) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| M | 185 (72.22%) | 277 (47.11%) | 71 (65.74%) |

| F | 70 (27.78%) | 311 (52.89%) | 37 (34.26%) |

| Parameters | Mean (±SD) | Mean (±SD) | Mean (±SD) |

| Age | 41.5 (13.2) | 36.7 (22.5) | 43 (10.5) |

| S. bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.6 (0.8) | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.85 (0.2) |

| S. albumin (gm/dL) | 3.8 (0.6) | 4.4 (0.5) | 4.3 (0.44) |

| SGOT (IU/L) | 49 (10) | 17 (6) | 22 (5.2) |

| SGPT | 52 (11) | 19 (8) | 19 (4.9) |

| ALP U/L | 77.8 (15.9) | 55 (18.9) | 62 (18.2) |

| AFP ng/mL | 25 (16.8) | 7 (3.1) | 8.2 (4.2) |

| ANA (U) | 0.7 (0.18) | 0.6 (0.25) | 0.5 (0.18) |

| S. creatinin | 0.8 (0.35) | 0.6 (0.39) | 0.9 (0.18) |

| S. cholesterol | 157 (25.9) | 149 (24.2) | 166 (21.5) |

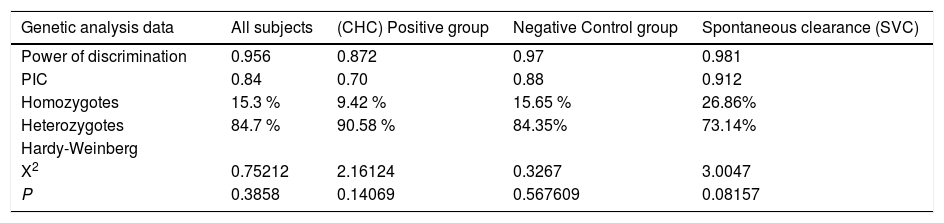

Genetic analysis data for HLA-DQB1 alleles in table 2 showed that the Matching Probability, Power of Discrimination, PIC (polymorphic information content), Homozygotes, Heterozygotes rates showed no significant differences between, chronic HCV(CHC), control and SVC groups. The analysis showed that the PIC for CHC, control subjects and SVC group ranged from (0.70 to 0.91) and heterozygosity ranged from (73.14 to 90.58) which indicates that this locus is highly polymorphic enough to do statistical analysis in Egyptians.

Descriptive genetic analysis data of HLA-DRB1 alleles in different groups

| Genetic analysis data | All subjects | (CHC) Positive group | Negative Control group | Spontaneous clearance (SVC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power of discrimination | 0.956 | 0.872 | 0.97 | 0.981 |

| PIC | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.88 | 0.912 |

| Homozygotes | 15.3 % | 9.42 % | 15.65 % | 26.86% |

| Heterozygotes | 84.7 % | 90.58 % | 84.35% | 73.14% |

| Hardy-Weinberg | ||||

| X2 | 0.75212 | 2.16124 | 0.3267 | 3.0047 |

| P | 0.3858 | 0.14069 | 0.567609 | 0.08157 |

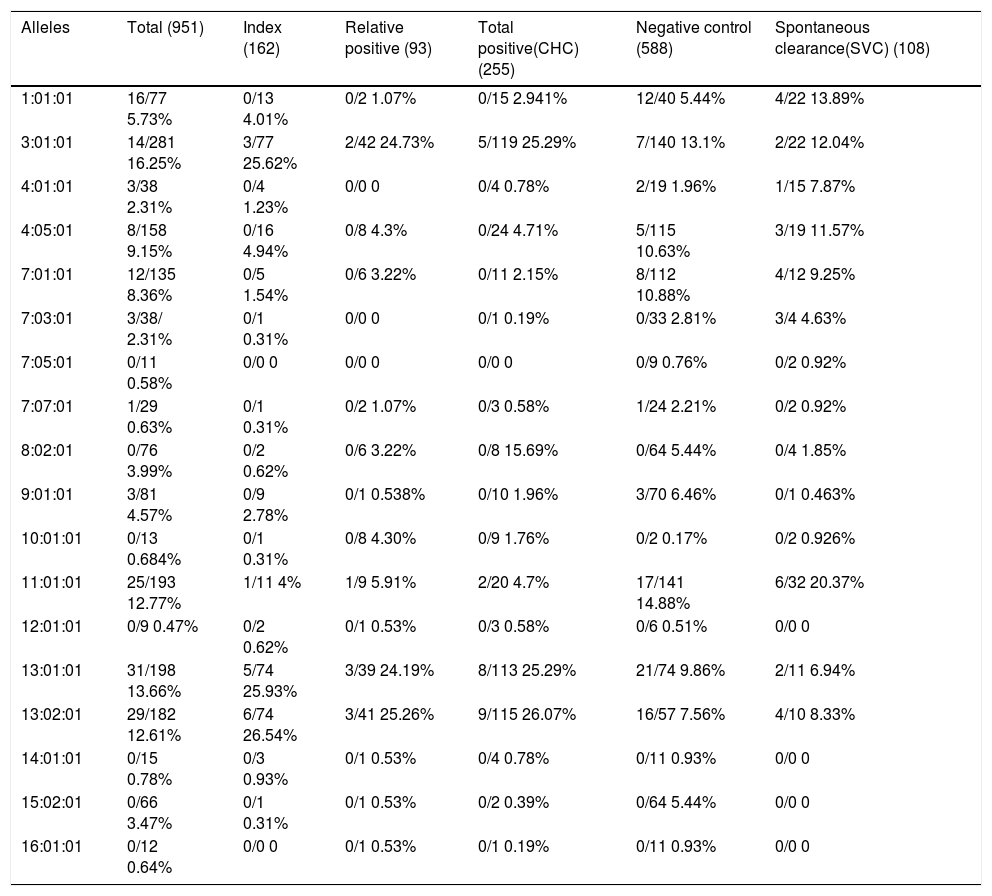

Analysis of the frequency of HLA-DRB1 alleles in CHC, control, and SVC groups revealed that DRB1*13:01:01 (26.07%) (Figure 1) is the most frequent allele in positive cases, followed by DRB1* 13:02:01 and DRB1*03:01:01 (25.29%) (Figure 1). In control, DRB1*11:01:01 is the most frequent allele (14.88%) followed by DRB1*3:01:01 (13.1%) and DRB1*07:01:01 (10.88%). In SVC group, DRB1*11:01:01 (20.37%) is the most frequent allele (Figure 2), followed by DRB1*1:01:01 (13.89%) and DRB1*03:01:01 (12.04%) wh ile other alleles showed less equal frequencies (Table 3).

Allele carriages and allele frequencies of DRB1 Loci in different study groups.

| Alleles | Total (951) | Index (162) | Relative positive (93) | Total positive(CHC) (255) | Negative control (588) | Spontaneous clearance(SVC) (108) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:01:01 | 16/77 5.73% | 0/13 4.01% | 0/2 1.07% | 0/15 2.941% | 12/40 5.44% | 4/22 13.89% |

| 3:01:01 | 14/281 16.25% | 3/77 25.62% | 2/42 24.73% | 5/119 25.29% | 7/140 13.1% | 2/22 12.04% |

| 4:01:01 | 3/38 2.31% | 0/4 1.23% | 0/0 0 | 0/4 0.78% | 2/19 1.96% | 1/15 7.87% |

| 4:05:01 | 8/158 9.15% | 0/16 4.94% | 0/8 4.3% | 0/24 4.71% | 5/115 10.63% | 3/19 11.57% |

| 7:01:01 | 12/135 8.36% | 0/5 1.54% | 0/6 3.22% | 0/11 2.15% | 8/112 10.88% | 4/12 9.25% |

| 7:03:01 | 3/38/ 2.31% | 0/1 0.31% | 0/0 0 | 0/1 0.19% | 0/33 2.81% | 3/4 4.63% |

| 7:05:01 | 0/11 0.58% | 0/0 0 | 0/0 0 | 0/0 0 | 0/9 0.76% | 0/2 0.92% |

| 7:07:01 | 1/29 0.63% | 0/1 0.31% | 0/2 1.07% | 0/3 0.58% | 1/24 2.21% | 0/2 0.92% |

| 8:02:01 | 0/76 3.99% | 0/2 0.62% | 0/6 3.22% | 0/8 15.69% | 0/64 5.44% | 0/4 1.85% |

| 9:01:01 | 3/81 4.57% | 0/9 2.78% | 0/1 0.538% | 0/10 1.96% | 3/70 6.46% | 0/1 0.463% |

| 10:01:01 | 0/13 0.684% | 0/1 0.31% | 0/8 4.30% | 0/9 1.76% | 0/2 0.17% | 0/2 0.926% |

| 11:01:01 | 25/193 12.77% | 1/11 4% | 1/9 5.91% | 2/20 4.7% | 17/141 14.88% | 6/32 20.37% |

| 12:01:01 | 0/9 0.47% | 0/2 0.62% | 0/1 0.53% | 0/3 0.58% | 0/6 0.51% | 0/0 0 |

| 13:01:01 | 31/198 13.66% | 5/74 25.93% | 3/39 24.19% | 8/113 25.29% | 21/74 9.86% | 2/11 6.94% |

| 13:02:01 | 29/182 12.61% | 6/74 26.54% | 3/41 25.26% | 9/115 26.07% | 16/57 7.56% | 4/10 8.33% |

| 14:01:01 | 0/15 0.78% | 0/3 0.93% | 0/1 0.53% | 0/4 0.78% | 0/11 0.93% | 0/0 0 |

| 15:02:01 | 0/66 3.47% | 0/1 0.31% | 0/1 0.53% | 0/2 0.39% | 0/64 5.44% | 0/0 0 |

| 16:01:01 | 0/12 0.64% | 0/0 0 | 0/1 0.53% | 0/1 0.19% | 0/11 0.93% | 0/0 0 |

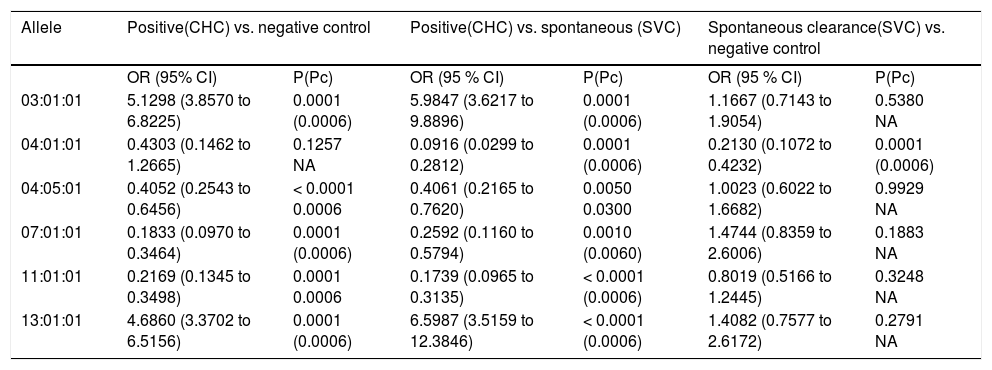

Table 4, comparing the distribution of HLA-DRB1 alleles between CHC, control and SVC groups revealed that: The carriage of allele 3:01:01 was significant in C HC group wh en compared to that of control and SVC groups (OR = 5.1289, 95% CI: 3.8570 to 6.8225, p = 0.001; and OR = 5.9847, 95% CI: 3.6217 to 9.8896, P < 0.000, 1 Pc = 0.0006) respectively. The carriage of allele 13:01:01 was significantly higher in CHC group when compared to control and SVC groups. After Bonferroni correction the result remain significant (OR = 4.6860, CI: 3.3702 to 6.5156, P < 0.0001 Pc = 0.0006 and OR = 6.5987, CI: 3.5159 to 12.3846, P = 0.0001, Pc = 0.0006) respectively. On the other hand, DRB1 *040501 and DRB1* 110101 alleles were more frequent in both control and SVC groups more than in CHC patients (for DRB1 *04051 OR = 0.4052 CI: 0.2543 to 0.6456, P = 0.0001, Pc = 0.0006 and OR = 0.4061, CI: 0.2165 to 0.7620 P = 0.005, Pc = 0.03 respectively. For DRB1*110101 OR = 0.2169, CI: 0.1345 to 0.3498, p = 0.0001, Pc = 0.0006 and OR = 0.1739, CI: 0.0965 to 0.3135, P < 0.0001 Pc = 0.0001 respectively). While DRB1*040101 was statistically significant in SVC group when compared to both CHC & control groups (OR = 0.0916, CI: 0.0299 to 0.2812, P = 0.0001, Pc = 0.0006 and OR = 0.2130, CI: 0.1072 to 0.4232, P = 0.0001, Pc = 0.0006). The carriage of alleles 7 family (7:01:01) was found to be significantly higher in both control and SVC groups when both were compared to CHC group even after Bonferroni correction the results remain significant (OR = 0.1833, CI: 0.0970 to 0.3464 P < 0.0001, Pc = 0.0006 and OR = 0.2592, CI: 0.1160 to 0.5794, P = 0.001, Pc = 0.006 respectively). Also no significant association was found when a comparison was made between control and SVC group (OR = 1.4744, CI: 0.8359 to 2.6006, P = 0.1883).

Odds ratio of common allele of DRB1 Locus in different study groups.

| Allele | Positive(CHC) vs. negative control | Positive(CHC) vs. spontaneous (SVC) | Spontaneous clearance(SVC) vs. negative control | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P(Pc) | OR (95 % CI) | P(Pc) | OR (95 % CI) | P(Pc) | |

| 03:01:01 | 5.1298 (3.8570 to 6.8225) | 0.0001 (0.0006) | 5.9847 (3.6217 to 9.8896) | 0.0001 (0.0006) | 1.1667 (0.7143 to 1.9054) | 0.5380 NA |

| 04:01:01 | 0.4303 (0.1462 to 1.2665) | 0.1257 NA | 0.0916 (0.0299 to 0.2812) | 0.0001 (0.0006) | 0.2130 (0.1072 to 0.4232) | 0.0001 (0.0006) |

| 04:05:01 | 0.4052 (0.2543 to 0.6456) | < 0.0001 0.0006 | 0.4061 (0.2165 to 0.7620) | 0.0050 0.0300 | 1.0023 (0.6022 to 1.6682) | 0.9929 NA |

| 07:01:01 | 0.1833 (0.0970 to 0.3464) | 0.0001 (0.0006) | 0.2592 (0.1160 to 0.5794) | 0.0010 (0.0060) | 1.4744 (0.8359 to 2.6006) | 0.1883 NA |

| 11:01:01 | 0.2169 (0.1345 to 0.3498) | 0.0001 0.0006 | 0.1739 (0.0965 to 0.3135) | < 0.0001 (0.0006) | 0.8019 (0.5166 to 1.2445) | 0.3248 NA |

| 13:01:01 | 4.6860 (3.3702 to 6.5156) | 0.0001 (0.0006) | 6.5987 (3.5159 to 12.3846) | < 0.0001 (0.0006) | 1.4082 (0.7577 to 2.6172) | 0.2791 NA |

HCV is a major health problem in Egypt affecting more than 10% of the population.2 Interplay between host and environmental factors are major determinants of HCV infection outcome.13 A number of baseline factors were reported as independent predictors for HCV infection14,15 including, low viral load, HCV genotype, absence of co infection as well as the host immunogenetic factors including human leukocyte antigen (HLA-DRB1) alleles.7,16

Polymorphism in the peptide binding regions of HLA-DR molecules determines antigenic specificities and strength of immune response to a given pathogen. It is well known that HLA-DRB1 alleles are crucial factors regulating cellular and humoral immune response through producing HLA-DR molecules participating in presentation of viral antigens on the surface of antigen presenting cells to CD4 + T cells.17,18 Genes of DR may determine HCV infection outcome and are prominent immunogenic factors influencing response to interferon treatment.19 The presence of specific HLA-DRB1 alleles may affect the HCV infection but associations vary among populations and results are controversial.3,20

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first multicentre one to test the association between HLA-DRB1 alleles and HCV infection outcome among the Egyptian families.

Studies of the relations between human leukocyte antigens and HCV infection showed inconsistent results. This inconstancy may be due to improper diagnosis and classification of the disease, population stratification, ethnic variation, or inadequate sample sizes.11 Another cause may be due to comparing the studied groups either (persistence of infection group or virus clearance group) with healthy control only.21 The problem of using healthy control subject is that about 80% of these subjects when exposed for the first time to HCV will develop chronicity while the rest showed spontaneous viral clearance (SVC).To overcome this inconstancy, subjects with Spontaneous viral clearance (SVC) should be compared to subjects with persistence of infection (CHC).3

Comparing the distribution of HLA-DRB1 alleles between CHC and other 2 groups revealed that the carriage of alleles 3:01:01 and 13:01:01 were significantly higher in CHC compared to control and SVC groups (i.e. These alleles associated with persistence of HCV infection).

On the other hand, DRB1*04:01:01, DRB1*04:05:01, DRB1*7:01:01 and DRB1*11:01:01 alleles were more frequent in SVC group when compared to CHC patients (i.e. These alleles associated with protection against HCV infection).

These results are consistent with previous results from different ethnic groups. In Caucasian American and in large multiracial cohort of U.S. women viral persistence was associated with DRB1*0301.11,22

Several studies conducted in Italian neonates, Spanish Irish, Northern European Caucasoid (NEC), France, Thailand and Indian populations showed that DRB1*03 was associated with persistence of HCV infection.8,19,23-27 On the other hand HLA-DRB1*11 seems to be protective against the development of severe forms of HCV infection in Spanish, Italian neonates, France and UK.19,28-30 Whereas in Japanese DRB1*1101 was more frequently found in carriers with persistently normal ALT values than in patients with CLD.31

A German study of North Europeans found that DRB1*13 was associated with susceptibility to HCV infection.32 However another study revealed that HLA-DRB1*11 allele was associated with a reduced risk for the development of HCV induced end stage liver disease.33

A meta-analysis carried on by Yee, et al. 2004 involving Caucasian population only from the period of 1997-2002 concluded that DRB1*11 was associated with protection against HCV infection.13,26,27,34-37 But these studies are generally smaller in size, less conclusive and performed with low resolution techniques.

In China it was found that DRB1*1101 was a protective allele and subjects with this allele are at a lower risk of developing chronic HCV.38

In Brazilian population it was confirmed that there were higher frequencies of HLA-DRB1*13 in patients compared with controls while DRB1*11was associated with protection from chronic HCV infection.39,40 Also in Pakistan and Iran DRB1*11 was associated with viral clearance.41,42 While in Iraq, it was found that the presence of DRB1*11 was significantly associated with increased risk for HCV infection.43

Reports from Egypt addressed that HLA-DRB1*03 individually or in combination with HLA-DRB1*04 act as a protective alleles against HCV infection.44 While In Egyptian HCV infected children it was reported that the most frequent alleles demonstrated among patients were DRB1 *03, DRB1 *04 and DRB1 *13 while DRB1*15 was significantly reduced among patients when compared with the control group.45 Shaker, et al. 2013 found that DRB1*04 and DRB1*11 were significantly more frequent in non responders than in responders. In contrast, DRB1*13 and DRB1*15 alleles were significantly more frequent in responders than in non responders. However this study compared the patients with the healthy control group not to the SVC group making these results inconsistent.10

There are other studies found that other HLA-DRB1 alleles were associated with the susceptibility to HCV infection. The frequency of DRB1*0405 was higher in HCV-infected patients than in uninfected subjects in Japan,31 whereas DRB1*1302 was more frequently found in carriers with persistently normal ALT values than in patients with CLD.3

Different studies carried on populations with different ethnic origin showed that the virus clearance was associated with the DRB1*1 and DRB1*13 in Caucasians (European and Americans) and with DRB1*12 in Non-Caucasian Americans.46 While the susceptibility to infection was connected to DRB1*3 and DRB1*7 in Caucasians (European and Americans) and to DRB1*12 in Caucasians Americans only. In a Midwestern American cohort reported the associations of DRB1*12 with HCV infection.21 Furthermore in Taiwan population it was suggested that DRB1*12 was significantly associated with the risk of HCC.47 In contradiction to these results, it was found that interaction between the KIR receptor gene 2DL3 with HLA-DRB1*1201 was associated with SVC.48

Several reports from different ethnic origin in the world reported that DRB1*07 allele was linked to viral persistence of HCV infection. (in British, Polish,Italian, Brazilian, Mid western Americans and Pakistanian populations.19,21,27,39,41,49 On the other hand in Iranian and Thailand HCV infected patient DRB1*0701 allele was found to be significantly presented in patients with HCV clearance.24,42

DRB1*01 is associated with viral clearance in a large multiracial cohort of U.S. women with a high prevalence of HCV and HIV.22 Same results were reported in white subjects and in Swiss Cohor, but another investigators reported that DRB1*1001 was associated with disease.27

Conflicting reports as regard DRB1*08 were recorded, whereas DRB1*0803 in Korean patients was associated with chronic HCV carriers,50 in Tunisian patients it was associated with clearance of circulating HCV.51

The frequency of DRB1*15 was associated with SVC but in Tunisian patients it appears to predispose to progression of liver disease.51

In conclusion, the present study suggested that certain HLA-DRB1 alleles namely DRB1*03:01:01 and DRB1* 13:01:01 may act as a risk alleles for HCV persistence while DRB1*04:01:01, DRB1*04:05:01, DRB1*7:01:01 and DRB1*11:01:01 alleles were associated with HCV clearance in the Egyptian families. This is important for disease management and deciding which person would most likely susceptible to HCV infection and which would not. It is strongly recommended that further investigations are needed to study more associations of these factors which may affect HCV susceptibility in the Egyptian population which may help towards eradication of HCV.

AcknowledgementWe would like to thank Medical Biochemistry department &xMedical Expreimental Research Centre (MERC)-Mansoura Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University for their kind help & support to complete routine laboratory work.

Abbreviations- •

Ab: antibody.

- •

AFP. alpha feto protein.

- •

CHC: chronic hepatitis C.

- •

CI: confidence interval.

- •

CV: chronic viraemia.

- •

ELISA: enzyme linked immune sorbont assay.

- •

HBV: hepatitis B virus.

- •

HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma.

- •

HCV: hepatitis C virus.

- •

HIV: human immundefeciency virus.

- •

HLA: human leukocyte antigen.

- •

HWE: hardy weinberg equilibrium.

- •

LC: liver cirrhosis.

- •

MHC: major histocompatibility complex.

- •

OR: odd

- •

PC: bonferroni correction.

- •

SBT: sequence-based typing.

- •

SCV: spontaneously cleared the virus.

- •

SSP-PCR: sequence specific primer-polymerase chain reaction.

- •

UV: ultra violet.

- •

VC: viral clearance.

The authors declares that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Financial SupportThis research was funded by Science & Technology Development Foundation (STDF), Project NO.1784 (TC/2/Health/2009/hep-1.3).