Endogenous opioids participate in growth regulation. Liver regeneration relates to growth. Thus, we explored the expression of methionine enkephalin and of the delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivities with a polyclonal rabbit antibody in deparaffinized liver of patients with chronic liver disease. Fifteen of a total of fifty-eight samples expressed both opioid receptor and methionine enkephalin immunoreactivities, one sample expressed receptor but not methionine enkephalin immunoreactivity, and two samples expressed methionine enkephalin but not receptor immunoreactivity. Ten of the 45 (22%) samples from patients with chronic hepatitis C, four of the eight (50%) samples from patients with chronic hepatitis B, one of the five (20%) samples from patients with autoimmune hepatitis expressed both met-enkephalin and delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivities. The expression of methionine enkephalin and delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivities suggests that methionine enkephalin exerts an effect in situ, which may include regulation of liver regeneration. However, another possibility that concerns an effect of methionine enkephalin in the liver arises. As morphine, which acts via opioid receptors, has been reported to increase hepatitis C virus replication in vitro and to interfere with the antiviral effect of interferon, methionine enkephalin, analogous to morphine, may enhance the replication of the hepatitis C virus in the liver of patients with this type of viral hepatitis, and interfere with the therapeutic effect of interferon. These results may explain at least in part, why some patients with chronic hepatitis C infection do not respond to interferon therapy.

The liver in cholestasis has features of neuroendocrine organs.1,2 The mRNA of preproenkephalin, the gene that codes for methionine enkephalin and methionine enkephalin containing peptides was found in the liver of adult rats with cholestasis secondary to bile duct resection,3 in contrast to its absence in the control group.3 The expression of methionine enkephalin immunoreactivity in cholestatic livers suggests that preproenkephalin derived endogenous opioids are made in the liver in cholestasis;3 in addition, the expression of methionine enkephalin immunoreactivity by the liver of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis,4 also suggests that the adult human liver may be a source of endogenous opioids in cholestasis. Furthermore, the detection of delta opioid receptor transcripts5 and delta opioid receptor-1 immunoreactivity in proliferating bile ductules5,6 in the livers of rats with cholestasis secondary to bile duct resection suggests not only the synthesis of this type of receptor by the biliary epithelium but also that methionine enkephalin exerts a local effect by binding to its opioid receptors.6

Endogenous opioids participate in organogenesis7-11 a process that concerns cell growth and regulation.12 The expression of methionine enkephalin immunoreactivity in the diseased liver, a process associated with regeneration,13 suggests that methionine enkephalin participates in the regulation of cell proliferation. This process concerns all types of liver diseases; however, in the context of endogenous opioids, studies in human diseased livers had been limited to primary biliary cirrhosis. Thus, the aim of our study was to explore the expression of methionine enkephalin and delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivities in the livers of patients with chronic liver disease secondary to chronic hepatitis C, chronic hepatitis B and autoimmune hepatitis.

MethodsSelection of tissuesThe study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. Pathology reports from liver biopsies were available for electronic retrieval from 1997, which defined the start of the period from which samples were gathered. Fifty eight samples from patients with liver disease identified by the histological reports from 1997 to 2005, when the study was conceived, were available for use. Forty five samples were identified as coming from patients with chronic hepatitis C, eight from patients with chronic hepatitis B, and five from patients with autoimmune hepatitis.

Immunohistochemistry staining for methionine enkephalin and the delta opioid receptor 1Formalin fixed, paraffin embedded liver tissue sections were obtained. The method for immunohistochemistry staining followed the principles previously described.4,5 Four micron thick sections were mounted onto silanized slides and prior to deparaffinization the sections were heated overnight at 58-60 ° C. The sections were deparaffinized through 3 changes of xylene bath for 3 minutes each, sections were dehydrated with different grades of ethyl alcohols (100%, 95% and 75%) for 3 minutes each and rinsed briefly with running tap water.

The heat induced epitope retrieval procedure was applied before immunostaining as follows, instead of full stop sections were placed in 0.01M citrate buffer for 2030 min at 97 ° C or higher and cooled for 15-20 min to reach room temperature. After rinsing with running tap water for 6-10 min the sections were placed in 3% hydrogen peroxide at room temperature and again rinsed briefly with running tap water.

The sections were transferred to a phosphate buffer solution/Tris buffer saline (PBS/TBS) bath for 5 min and then incubated for 30 minutes with primary antibodies to the delta opioid receptor, at a dilution of 1:750, or to methionine at a dilution of 1:200 (ImmunoStar, Hudson, WI) and rinsed with PBS/ TBS. Subsequently, the slides were stained with LSAB Plus system (labeled streptavidin biotin, Dako #K-0690, Carpinteria, Ca) followed by DAB Plus, a substrate chromogen, (diaminobenzidine, Dako #K-3467). After counter staining with hematoxylin I, the preparations were rinsed with running tap water, dehydrated through ethyl alcohol baths of 75%, 95%, and 100% and cleared with xylene baths. The slides were mounted with permount (Fisher Scientific #SP15-500). Human brain tissue was used as positive control for methionine enkephalin.

All the slides were examined for the expression of methionine enkephalin immunoreactivity and delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivity.

Statistical analysisThe percentage of samples that expressed methionine enkephalin and delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivity, alone or in combination was determined. The data were analyzed by the use of the Fisher’s exact test14 and by examining the correlation between variables by a parametric test,15 as appropriate.

ResultsArchived liver tissues were identified from 45 cases of chronic hepatitis C, eight cases of chronic hepatitis B, and five cases of autoimmune hepatitis.

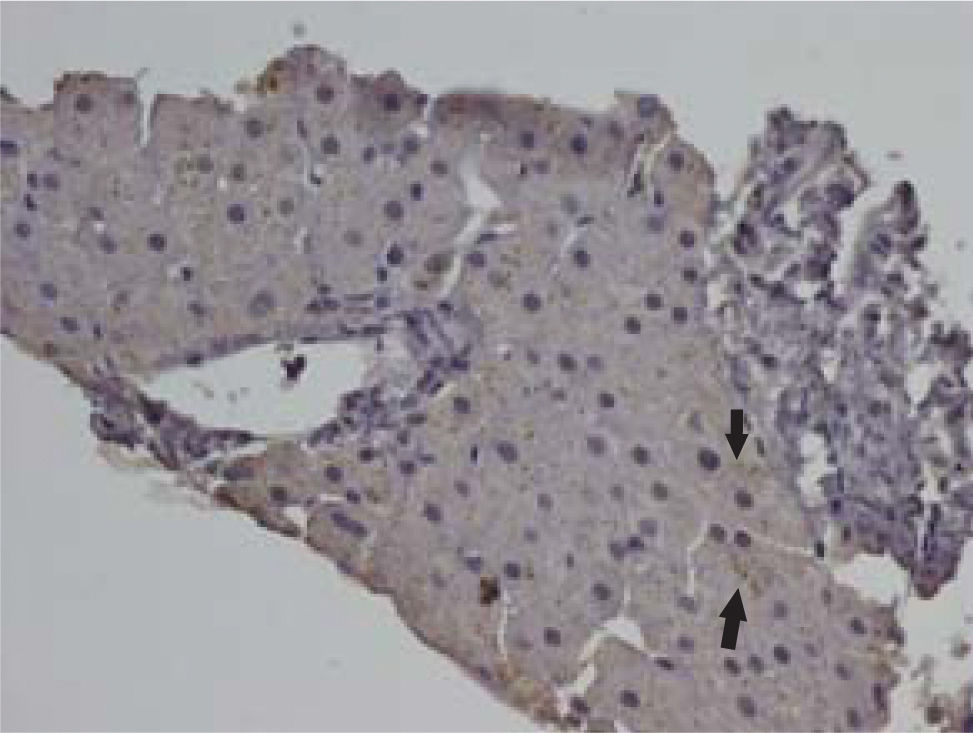

Of the 58 liver samples studied, 18 expressed either methionine enkephalin immunoreactivity, delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivity, or both. Fifteen of the 58 samples (25.8%) expressed both delta opioid receptor 1 and methionine enkephalin immunoreactivities, 1 (1.7%) expressed delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivity, but not methionine enkephalin immunoreactivity, and 2 (3.4%) expressed methionine enkephalin immunoreactivity but not delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivity (Figure 1). Methionine enkephalin immunoreactivity (Figure 2) and delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivity (Figure 3) were predominantly localized to the cytoplasm of hepatocytes with infrequent expression on their cell membranes and in bile ducts. In some cases, the methionine enkephalin immunoreactivity appeared as coarse granules, as previously observed in the liver of rats with cholestasis3 and in the liver from patients with primary biliary cirrhosis.4

Ten of the 45 (22%) of samples from patients with chronic hepatitis C, four of eight (50%) samples from patients with chronic hepatitis B, and one of five (20%) samples from patients with autoimmune hepatitis expressed both methionine enkephalin and delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivities (Figure 4). There was no significant difference in the combined expression of methionine enkephalin immunoreactivity and delta opioid receptor 1 among the three groups (p = 0.26).

Percentage of the total number of liver samples (58) expressing methionine enkephalin immunoreactivity (MEIR) and delta opioid receptor immunoreactivity (DORI) in chronic hepatitis C (HCV) (10 of 45, 22%), chronic hepatitis B (four of eight, 50%) and in autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) (one of five, 20%).

The expression of methionine enkephalin and delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivities was associated with bridging fibrosis and nodular regeneration in seven of the ten (70%) samples that co-expressed the peptide and receptor immunoreactivities in the group of samples from patients with chronic hepatitis C, in four or the eight (50%) samples from patients with chronic hepatitis B, and in one sample (20%) from patients with autoimmune hepatitis (Figure 5); however, these histological features were also present in the livers that did not express methionine enkephalin and delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivities. The correlation between the expression of methionine enkephalin and delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivities and fibrosis and nodular regeneration was not statistically significant (Pearson correlation coefficient, r2, of 0.42, p = 0.5). Twenty of the 32 cases (62%) of chronic hepatitis C that did not express methionine enkephalin and delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivities displayed bridging fibrosis, and 12 (37%) displayed nodular regeneration. The four of the eight cases of chronic hepatitis B that did not express methionine enkephalin and delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivities displayed bridging fibrosis and nodular regeneration. The three samples from autoimmune hepatitis that did not express methionine enkephalin and delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivities displayed bridging fibrosis, and two displayed nodular regeneration.

DiscussionIn this study, methionine enkephalin and delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivities were detected in archived liver tissues from patients with chronic hepatitis C, chronic hepatitis B and autoimmune hepatitis. The majority of the samples that expressed the immunoreactivities studied coexpressed methionine enkephalin and delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivities (i.e. fifteen of the 58 samples (25.8%)).

The findings in this study confirm that methionine enkephalin and delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivities can be expressed by livers affected by diseases characterized by hepatocellular injury (e.g. viral hepatitis), as already shown in the liver affected by a disease characterized by cholangiopathy (i.e. primary biliary cirrhosis). Furthermore, in this study, as well as in the study conducted in the liver of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis, methionine enkephalin immunoreactivity was found mostly in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes.16 This finding was first observed in a study of livers from rats with cholestasis secondary to bile duct resection.3 In that study, in situ hybridization histochemistry revealed the expression of preproenkephalin-mRNA on cells distinct from biliary epithelial cells, some of which appeared to be proliferating bile ductular cells, and others might have been hepatocytes.3 Taken together these data tend to suggest that methionine enkephalin can be synthesized by the hepatocyte. The effect of methionine enkephalin, however, is opioid receptor mediated (e.g. delta opioid receptor 1); thus, as delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivity can be observed on the cell membranes of some hepatocytes and bile duct cells in human livers (this study) and on the bile ducts in the liver of rats with cholestasis, the effect of methionine enkephalin may be on the hepatocyte and on biliary epithelial cells by an autocrine and paracrine fashion, respectively.

Most of the samples expressing methionine enkephalin and delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivities displayed bridging fibrosis and nodular regeneration; however, the expression of the peptide and the receptor was not specific for advanced disease, as the histological findings of fibrosis and regeneration were also present in the liver samples that did not express the peptide and the receptor. Alternatively, a correlation between methionine enkephalin and delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivities and histological findings consistent with advanced disease may not have been detected because of the inherent sampling error in needle liver biopsies and the limited sample of this study.

The expression of methionine enkephalin in developing tissues7-11 suggests, and the studies on biliary epithelial cells,6 tend to confirm that the role of methionine enkephalin is to regulate the proliferation of growing tissue. This process may be an effort to prevent missteps that may lead to malignant transformation of rapidly dividing cells. In this context, methionine enkephalin has been reported to decrease cellular proliferation in malignant tumors (e.g. colon, pancreas).17,18

An interesting possibility that concerns the role of methionine enkephalin in situ in the livers of patients with viral hepatitis merits consideration. Morphine is an alkaloid that, like the endogenous opioid peptides, exerts its effect by binding to opioid receptors. It was reported that morphine increases hepatitis C expression in hepatitis C-replicon containing liver cells.19 This effect of morphine was reported to be mediated by the activation of NF-KB, a nuclear transcription factor that controls viral replication.19 The addition of the opiate antagonist naltrexone to the hepatitis C-replicon system prevented the effect of morphine on hepatitis C virus expression, suggesting that the morphine effect was opioid receptor mediated.19 Furthermore, the addition of interferon to the hepatitis C-replicon system was associated with a decrease in the production of hepatitis C particles; however, the application of morphine interfered with the inhibitory effect of interferon on the production of the hepatitis C virus.19

Methionine enkephalin can bind to the same receptors to which morphine binds.20,21 In this context, and analogous to the effect of morphine in the hepatitis C-replicon system,19 it has been hypothesized that methionine enkephalin arising from the liver in patients with chronic hepatitis C may stimulate the replication of the virus, and interfere with the effect of interferon, the foundation of antiviral therapy for this disease.22 Indeed, the lack of effect of interferon alone or in combination with ribavirin in a substantial number of patients, in particular in those with cirrhosis, is a real clinical challenge.23 It is possible that some of the patients who do not respond to interferon therapy have activity of methionine enkephalin in their livers.

In summary, methionine enkephalin and delta opioid receptor 1 immunoreactivities were detected in the liver of patients with viral hepatitis C and B and autoimmune hepatitis. There are sufficient experimental data to support a role of methionine enkephalin in the regulation of liver regeneration, and its effect may be regulatory and beneficial. Conversely, the activity of methionine enkephalin in the liver may be detrimental in chronic hepatitis C. In this context, methionine enkephalin may increase viral replication and hence, viral load, which correlates with poor response to therapy, and may impede the antiviral effect of interferon(s), which is the basis of all current and likely future treatment regimens for this disease. The hypothesis of the detrimental effect of methionine enkephalin on the livers infected with the hepatitis C virus offers a mechanism for the lack of consistent therapeutic effect of the current treatments of this common liver disease.22 If confirmed, this hypothesis may provide a rationale for pilot studies of opiate antagonists in combination with current antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C in patients who express methionine enkephalin immunoreactivity in their livers.

AcknowledgementsThe authors thank Mr. Jaik Koo, Supervisor of Anatomical Pathology, Histology and Immunohistochemistry Laboratory, for his work on Immunohistochemistry in this study.