Data about 30-day readmission for patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) and their contribution to CLD healthcare burden are sparse. Patterns, diagnoses, timing and predictors of 30-day readmissions for CLD from 2010-2017 were assessed.

Materials and MethodsNationwide Readmission Database (NRD) is an all-payer, all-ages, longitudinal administrative database, representing 35 million discharges in the US population yearly. We identified unique patients discharged with CLD including hepatitis B (HBV) and C (HCV), alcoholic liver disease (ALD) and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) from 2010 through 2017. Survey-weight adjusted multivariable analyses were used.

ResultsFrom 2010 to 2017, the 30-day readmission rate for CLD decreased from 18.4% to 17.8% (p=.008), while increasing for NAFLD from 17.0% to 19. 9% (p<.001). Of 125,019 patients discharged with CLD (mean age 57.4 years, male 59.0%) in 2017, the most common liver disease was HCV (29.2%), followed by ALD (23.5%), NAFLD (17.5%), and HBV (4.3%). Readmission rates were 20.5% for ALD, 19.9% for NAFLD, 16.8% for HCV and 16.7% for HBV. Compared to other liver diseases, patients with NAFLD had significantly higher risk of 30-day readmission in clinical comorbidities adjusted model (Hazard ratio [HR]=1.08 [95% confidence interval 1.03-1.13]). In addition to ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, higher number of coexisting comorbidities, comorbidities associated with higher risk of 30-day readmission included cirrhosis for NALFD and HCV; acute kidney injury for NAFLD, HCV and ALD; HCC for HCV, and peritonitis for ALD. Cirrhosis and cirrhosis-related complications were the most common reasons for 30-day readmission, followed by sepsis. However, a large proportion of patients (43.7% for NAFLD; 28.4% for HCV, 39.0% for HBV, and 29.1% for ALD) were readmitted for extrahepatic reasons. Approximately 20% of those discharged with CLD were readmitted within 30 days but the majority of readmissions occurred within 15 days of discharge (62.8% for NAFLD, 63.7% for HCV, 74.3% for HBV, and 72.9% for ALD). Among readmitted patients, patients with NAFLD or HCV readmitted ≤30-day had significantly higher costs and risk of in-hospital mortality (NAFLD +5.69% change [95% confidence interval, 2.54%-8.93%] and odds ratio (OR)=1.58 [1.28-1.95]; HCV +9.85% change [95%CI:6.96%-12.82%] and OR=1.31, 1.08-1.59).

ConclusionsEarly readmissions for CLD are prevalent causing economic and clinical burden to the US healthcare system, especially NAFLD readmissions. Closer surveillance and attention to both liver and extrahepatic medical conditions immediately after CLD discharge is encouraged.

Hospitals continue to strive to provide value-based care to optimize quality of care and resource utilization [1–3]. A hospital's 30-day readmission rate is used by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid to gauge the value of care and monetarily penalizes hospitals determined to have unreasonably high readmission rates [4–7]. Readmissions also place a major burden on patients both financially and psychologically [8,9].

Chronic liver disease (CLD), comprised of chronic viral hepatitis B and C (HBV, HCV), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and alcohol related liver disease (ALD), and its complications are the 11th leading cause of death globally, 5th in the United States for persons aged 45–64 and 6th for 25–44 years which has led to increased healthcare utilization from disease complexity [10–12]. The increased healthcare utilization and potential loss of productivity may create a significant societal economic burden [11,12].

Over the recent years the primary etiologies of CLD have changed. Due to the advent of curative treatment for HCV and excellent viral suppression medications and prevention immunization for HBV, cases of these diseases appear to be decreasing while the incidence and prevalence of NAFLD, a complex metabolically based liver disease, is increasing paralleling the global rise in type 2 diabetes and obesity. In addition, reports have indicated that there has been an increase in the rates of alcohol use disorder especially among the younger population which may be leading to an increase in ALD [13].

However, how much of the healthcare economic burden of CLD related to readmissions is unknown [14]. Therefore, we used the Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) database to assess patterns, readmission diagnoses, risk factors, costs, timing of 30- day readmission, readmission predictors, and sex differences for patients with CLD who had recently been discharged.

2Materials and Methods2.1Data sourcesThis prospective cohort study used the Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD), published by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) as part of the Healthcare Costs and Utilization Project (HCUP). The NRD is an all-payer database which provides weighted adjustments to produce nationally representative estimates. The NRD includes a sample of 18 million discharges each year from 21 geographically dispersed states, representing approximately 35 million discharges in the US population by the NRD weighting methods [15]

2.2Study sampleWe used NRD data from 2010 to 2017 to identify unique patients discharged with CLD. Using Hirode's coding algorithm [16], CLD diagnoses were identified as a primary discharge diagnosis of CLD or a primary discharge diagnosis of another liver-related complications (eg. cirrhosis) in combination with a secondary diagnosis of CLD [16,17]. The CLD diagnoses were split into 5 etiologies (chronic hepatitis B (HBV) and C (HCV), alcoholic liver disease (ALD) and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and other CLD using the ICD codes. Because NAFLD is typically under-coded in clinical practice (K76.0, K75.81), we presumed that NAFLD also included those individuals who were coded for cryptogenic liver disease (K76.9, K74.6) in the absence of any other causes of chronic liver diseases (such as HCV, HBV, ALD, autoimmune hepatitis, other inflammatory liver diseases, etc) or excessive alcohol use, based on a prior published algorithm [18,19]. Elixhauser Comorbidity Index were used to identify other comorbidities [20–25]. Please see Supplementary Table 1 for a detailed list of ICD codes mapped to CLD.

To track patients’ readmissions over time, we converted admission-level data to patient-level data using patient identifiers in the NRD database. We identified patients’ initial discharge with CLD who were aged 18 years or older. Discharges that occurred in January were excluded to ensure no hospitalizations in the preceding 30 days and those in December were also excluded to ensure a minimum of a 30-day readmission period (patients are not followed year to year in the NRD data). Using methods from the Centers for Medicare & Medical Services (CMS), we excluded discharges for patients who died, left against medical advice, were transferred to another acute-care hospital, those missing discharge positions, or length of stay (LOS). After the initial CLD discharge, any subsequent hospitalization which occurred from February to November was added to our study cohort [15,20].

2.3Outcomes2.3.130-day readmission and readmission timeThe 30-day readmissions were defined as all-cause readmission to any hospital following discharge with CLD. Per CMS methodology, only the first readmission within 30 days of discharge was considered a 30-day readmission. Time to readmission was counted from baseline (time when a subject was discharged) to date of readmission or November 30, whichever came first.

As a sensitivity analysis, we calculated the 30-day readmission rate at the admission level by the number of eligible 30-day admissions divided by the total number of eligible index admissions. Subsequent hospitalizations which occurred after 30 days following discharge were counted as index admissions if met inclusion criteria.

2.3.2Reasons for readmission by time after discharge with CLD and concordanceWe categorized readmission diagnoses using the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (ECI) software developed by Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP) and our ICD code for CLD-related complications. Cirrhosis-related complications included Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), ascites, variceal hemorrhage, hepatic encephalopathy, and hepatorenal syndrome.

We identified the 15 most common reasons for readmissions (cirrhosis, cirrhosis-related complications, acute kidney injury (AKI), cellulitis, peritonitis, sepsis, alcohol use disorder, pneumonia, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)) [20–23]. Readmission reasons were then grouped by time period following the initial discharge (1-7, 8-14, 15-21, and 22-30 days). We calculated the concordance (those with the same diagnosis) and discordance (those with a different diagnosis) to compare the discharge diagnosis and readmission diagnosis.

2.3.3Health care utilizationHospital charges were inflation-adjusted to 2017 US dollars using the medical component of Consumer Price Index year 2017 [26]. Charges, the amount that hospitals billed for services, may differ from costs or the actual expenses. Therefore, hospital costs were also estimated using the AHRQ charge-to-cost ratio developed by the AHRQ [27].

2.3.4Demographic and clinical characteristicsWe described sex, the payer (Medicare, Medicaid, private, other pay), discharge disposition (routine, skilled nursing facility, home health care, against medical advice, and died), clinical characteristics (liver disease etiology, HCC, cirrhosis, and comorbidities), and hospital characteristics (bed size, urban/rural, teaching status and ownership). Comorbidities were defined using the ECI software at the primary or secondary diagnosis.

2.4Data analysisThe sample design elements (clusters, strata, and trend weights) provided by the NRD were used to create national estimates for all US hospitals and their discharges across the study period.

Descriptive statistics in demographic, clinical, and health care utilization characteristics were tested by using Rao-Scott chi-square for categorical variables or Wald test for continuous variables. The standard errors of proportions/means were estimated using the Taylor linearization method and 95% confidence intervals were estimated using the Wald method.

A survey-weight logistic regression model was used to evaluate trends in the proportion of 30-day readmission after being discharged with CLD from 2010 through 2017.

Survey-weight adjusted multivariable Cox model was used to compare the risk of each liver disease for a 30-day readmission and determine baseline factors associated with risk for 30-day readmission among patients discharged with CLD. The proportional hazards assumption of the Cox models was examined by testing time-dependent covariates, which showed no significant departure from proportionality over time (P > .05) [28].

The independent association between 30-day readmission and cost was estimated using coefficients from weight-adjusted multivariable generalized linear regression (GLM) model with Gamma distribution, which was exponentiated to yield a percentage change, whereas the independent association with in-hospital mortality was evaluated using a survey-weight logistic regression model.

The number of individuals in each group displayed in this study was reported by multiplying the estimated weight percentage by the total number of individuals in the full sample. All analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

2.5Ethical statementThis study followed the data use agreement as defined by the HCUP and AHRQ and was considered exempt by the Inova Institutional Review Board.

3Results3.1Trends in the proportion of discharges and 30-day readmissionsThe number of patients discharged with CLD increased by +97.8% from 63,204 in 2010 to 125,019 in 2017. During this period (2010-2017), patients with NAFLD increased by +103% from 10,638 to 21,544; ALD increased by +82.2% from 16,023 to 29,188; HCV increased by +63.3% from 21,733 to 35,488; and HBV increased by +63.0% from 2,619 to 4,270.

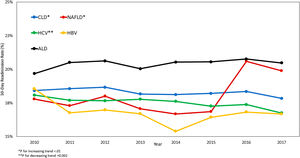

Overall, 30-day readmission rate for patients with CLD decreased from 18.4% in 2010 to 17.8% in 2017 [trend p-value = 0.0076]. For type of liver disease, during the same period, readmission rate for NAFLD increased from 17.8% to 19.9% (Trend p < .0001), whereas the readmission rate for HCV decreased from 18.1% to 16.8% (Trend p = 0.0017). There were no changes in readmission rates for HBV and ALD (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Our findings remained robust in our sensitivity analyses using admission level data, instead of patient-level data except ALD was found to have increased (20.9% to 22.5%, P = 0.0001) (Supplementary Table 2).

Trends in 30-Day Readmission Rate For CLD, NAFLD, HCV, HBV, and ALD.

Data displayed as weighted percentages (95% confidence Interval) except where otherwise noted. Test for trends was performed by including year as a continuous variable in logistic regression model.

Of 125,019 patients discharged with CLD (mean age 57.4 years, male 59.0%) in 2017, the most common liver disease etiology was HCV (29.2%), followed by ALD (23.5%), NAFLD (17.5%), and HBV (4.3%). Characteristics of patients discharged with CLD were summarized by types of liver diseases (Table 2). Compared to viral hepatitis, patients discharged with NAFLD were more likely to be older, female, more likely to have Medicare insurance, cirrhosis, cirrhosis-related complications, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic abnormalities (such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes), and more likely to be discharged with home health care or skilled nursing facility. Compared to NAFLD and ALD, patients with HCV and HBV were more likely to have HCC and sepsis. Since NAFLD has a definite sexual dimorphism, we further studied sex disparity among NAFLD patients (Supplementary Table 3). Compared to females with NAFLD, males with NAFLD were more likely to be discharged with routine care and to have private insurance, cirrhosis, HCC, acute kidney injury, cardiovascular disease but were less likely to have diabetes and obesity.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients Discharged With NAFLD, HCV, HBV, or ALD, U.S. 2017.

| Patients Discharged with NAFLD (n=21,544) | Patients Discharged with HCV⁎⁎ (n=35,488) | Patients Discharged with HBV⁎⁎ (n=4,270) | Patients Discharged with ALD (n=29,188) | Patients Discharged with CLD (n=125,019) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (SE) | 65.70 (0.13) | 54.53 (0.17) | 56.88 (0.33) | 54.82 (0.10) | 57.43 (0.09) |

| 18-44 | 6.01 (0.19) | 21.21 (0.49) | 20.88 (0.84) | 19.65 (0.32) | 18.14 (0.22) |

| 45-64 | 37.24 (0.40) | 58.49 (0.37) | 48.18 (0.81) | 59.62 (0.32) | 50.75 (0.22) |

| 65-74 | 31.79 (0.32) | 16.12 (0.31) | 19.21 (0.68) | 15.87 (0.26) | 20.18 (0.17) |

| ≥75 | 24.95 (0.44) | 4.17 (0.14) | 11.73 (0.62) | 4.85 (0.14) | 10.93 (0.17) |

| Male, % | 48.01 (0.39) | 64.35 (0.32) | 65.54 (0.77) | 68.67 (0.34) | 58.98 (0.18) |

| Disposition Status, % | |||||

| Routine | 62.56 (0.43) | 72.20 (0.40) | 72.66 (0.90) | 71.12 (0.37) | 69.89 (0.27) |

| SNF/ICF/other | 17.05 (0.32) | 13.48 (0.28) | 11.71 (0.57) | 14.21 (0.27) | 14.23 (0.17) |

| Home Health care | 18.77 (0.36) | 12.84 (0.32) | 14.23 (0.71) | 12.81 (0.27) | 14.26 (0.24) |

| Expected primary payer, % | |||||

| Medicare | 63.69 (0.45) | 35.26 (0.38) | 39.82 (0.96) | 30.50 (0.34) | 41.14 (0.25) |

| Medicaid | 10.33 (0.28) | 36.29 (0.65) | 24.97 (0.91) | 28.82 (0.57) | 24.56 (0.44) |

| Private | 20.89 (0.42) | 13.93 (0.33) | 22.57 (0.80) | 26.68 (0.46) | 22.95 (0.33) |

| Other Pay | 5.08 (0.21) | 14.51 (0.52) | 12.65 (0.80) | 14.00 (0.41) | 11.35 (0.30) |

| Elective admission, % | 6.06 (0.43) | 4.39 (0.31) | 6.81 (0.76) | 3.64 (0.25) | 4.47 (0.27) |

| Cirrhosis, % | 78.10 (0.38) | 40.29 (0.49) | 28.74 (0.80) | 77.28 (0.35) | 50.53 (0.34) |

| Cirrhosis complications, % | 62.00 (0.52) | 40.30 (0.49) | 40.23 (0.96) | 72.63 (0.34) | 49.42 (0.35) |

| Ascites | 32.53 (0.49) | 19.56 (0.31) | 17.73 (0.65) | 50.19 (0.39) | 27.67 (0.26) |

| Variceal hemorrhage | 25.75 (0.39) | 17.42 (0.27) | 13.77 (0.54) | 33.89 (0.34) | 21.49 (0.21) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 25.55 (0.50) | 14.98 (0.30) | 14.28 (0.62) | 21.66 (0.34) | 17.67 (0.26) |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | 2.38 (0.13) | 1.28 (0.07) | 1.18 (0.16) | 4.48 (0.17) | 2.17 (0.07) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 5.69 (0.28) | 9.14 (0.36) | 13.20 (0.93) | 2.44 (0.13) | 5.14 (0.20) |

| Acute kidney injury, % | 29.93 (0.35) | 24.28 (0.30) | 23.85 (0.72) | 23.94 (0.32) | 25.99 (0.20) |

| Cellulitis, % | 9.47 (0.24) | 20.27 (0.34) | 7.66 (0.45) | 6.06 (0.15) | 11.51 (0.16) |

| Peritonitis, % | 3.79 (0.14) | 2.96 (0.11) | 2.49 (0.27) | 4.88 (0.15) | 3.34 (0.07) |

| Sepsis, % | 25.56 (0.47) | 33.22 (0.51) | 28.26 (0.94) | 17.42 (0.30) | 29.74 (0.36) |

| Cardiovascular disease, % | 36.57 (0.45) | 24.22 (0.31) | 24.76 (0.76) | 21.76 (0.30) | 27.41 (0.23) |

| Hypertension, % | 65.75 (0.50) | 49.90 (0.45) | 50.76 (0.95) | 47.62 (0.41) | 54.65 (0.29) |

| Diabetes, % | 53.96 (0.47) | 25.80 (0.37) | 29.22 (0.78) | 19.53 (0.29) | 31.78 (0.26) |

| Obesity, % | 25.06 (0.40) | 11.30 (0.22) | 10.40 (0.55) | 12.52 (0.28) | 18.39 (0.23) |

| Pneumonia, % | 14.54 (0.31) | 17.59 (0.26) | 17.22 (0.66) | 8.72 (0.18) | 14.77 (0.16) |

| COPD, % | 24.48 (0.36) | 27.92 (0.33) | 20.00 (0.66) | 17.77 (0.28) | 23.62 (0.21) |

| ECI, mean (SE) | 5.21 (0.02) | 4.54 (0.02) | 4.18 (0.04) | 5.38 (0.02) | 4.92 (0.02) |

| Ownership of hospital, % | |||||

| Government | 10.65 (0.84) | 13.55 (1.19) | 13.14 (1.30) | 12.17 (0.97) | 11.82 (0.92) |

| Private, not-profit | 76.53 (1.23) | 74.22 (1.46) | 76.38 (1.63) | 75.19 (1.27) | 75.72 (1.22) |

| Private, invest-own | 12.81 (0.89) | 12.24 (0.93) | 10.48 (1.01) | 12.64 (0.87) | 12.46 (0.82) |

| Hospital bed-size, % | |||||

| Small | 16.53 (0.65) | 15.42 (0.70) | 11.52 (0.78) | 16.81 (0.60) | 16.39 (0.53) |

| Medium | 27.17 (0.95) | 26.84 (0.99) | 25.39 (1.23) | 28.64 (0.83) | 27.56 (0.73) |

| Large | 56.30 (1.11) | 57.74 (1.16) | 63.08 (1.51) | 54.55 (1.00) | 56.05 (0.90) |

| Hospital Location/teaching status, % | |||||

| Non-metropolitan hospital | 9.75 (0.50) | 7.08 (0.45) | 4.70 (0.58) | 7.98 (0.43) | 7.90 (0.38) |

| Metropolitan non-teaching | 67.04 (0.92) | 71.21 (0.93) | 76.95 (1.23) | 67.26 (0.85) | 68.86 (0.75) |

| Metropolitan teaching | 23.21 (0.74) | 21.71 (0.80) | 18.35 (1.09) | 24.77 (0.73) | 23.24 (0.64) |

| Length of Stay, d | 5.47 (0.08) | 6.44 (0.07) | 6.23 (0.13) | 6.35 (0.06) | 6.11 (0.05) |

| Total Admissions⁎⁎ | 1.85 (0.01) | 1.74 (0.01) | 1.61 (0.02) | 1.83 (0.01) | 1.74 (0.01) |

| Total Average Cost⁎⁎,†, $ | $27,651 (679) | $27,971 (496) | $29,940 (1,196) | $29,543 (484) | $27,688 (439) |

SE, Standard Error; SNF, Skilled Nursing Facility; ICF, Intermediate Care Facility; COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; ECI, Elixhauser Comorbidity Index. *Coexists HCV and HVB were excluded.

After adjustments of patients’ demographic and hospital characteristics, compared to other liver diseases, patients with ALD had a 36% higher risk (Hazard Ratio [HR] = 1.36, 95% CI, 1.30-1.42) of 30-day readmission, followed by those with NAFLD (HR = 1.23, 1.17-1.29), and those with HCV (HR = 1.08, 1.03-1.12). Those with HBV did not demonstrate an increased risk for readmission. However, when clinical comorbidities were added to the models, only patients with NAFLD continued to demonstrate a significantly higher risk of 30-day readmission (HR = 1.06, 1.01-1.11) (Table 3).

Multivariable Hazard Ratio of Different Liver Diseases for 30-day Readmission After Discharged with CLD.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| NAFLD | 1.23 (1.17 - 1.29) | <.0001 | 1.06 (1.01 - 1.11) | 0.0274 |

| HCV* | 1.08 (1.03 - 1.12) | 0.001 | 1.00 (0.96 - 1.05) | 0.9875 |

| HBV* | 1.06 (0.98 - 1.16) | 0.1674 | 1.02 (0.94 - 1.11) | 0.5971 |

| ALD | 1.36 (1.30 - 1.42) | <.0001 | 1.01 (0.96 - 1.06) | 0.7241 |

HR, Hazard Ratio; CI, confidence interval. Time to readmission was counted from baseline (defined as the time when a subject discharged) to date of readmission or November 30, 2017, whichever came first.

Coexists HCV and HBV were excluded. HRs and 95% CI were weighted to all-payer database. Model 1 adjusted for Age, sex, disposition status, expected primary payer, ownership of hospital, hospital bed-size and hospital location. Model 2 adjusted for model 1 + Ascites, Variceal hemorrhage, Hepatic encephalopathy, Hepatorenal syndrome, HCC, Acute kidney injury, Cellulitis, Peritonitis, Sepsis, CVD, Hypertension, Diabetes, Obesity, Pneumonia, Elixhauser Comorbidity Index

The association of demographic and clinical variables with 30-day readmission was determined by estimating comorbidity-adjusted HRs across the different types of liver diseases (Table 4).

Multivariable Hazard Ratio of Risk Factors for 30-day readmission After Discharged with Chronic Liver Disease, Stratified by Different Liver Diseases.

| NAFLD | HCV* | HBV* | ALD | CLD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age | CLD | |||||||||

| Aged 18-44 | 1.24 (1.04 - 1.47) | 0.0178 | 0.82 (0.71 - 0.95) | 0.009 | 1.30 (0.87 - 1.93) | 0.1984 | 1.26 (1.07 - 1.49) | 0.0058 | 1.08 (1.01 - 1.16) | 0.02 |

| Aged 45-64 | 1.22 (1.10 - 1.35) | 0.0002 | 1.01 (0.89 - 1.15) | 0.8651 | 1.27 (0.95 - 1.70) | 0.1017 | 1.17 (1.02 - 1.35) | 0.03 | 1.14 (1.08 - 1.20) | ≤.0001 |

| Aged 65-74 | 1.16 (1.07 - 1.27) | 0.0007 | 0.99 (0.87 - 1.12) | 0.8694 | 1.06 (0.80 - 1.40) | 0.6835 | 1.08 (0.94 - 1.25) | 0.2702 | 1.08 (1.03 - 1.13) | 0.0031 |

| Aged ±75 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Male | 1.01 (0.95 - 1.07) | 0.8307 | 1.06 (0.99 - 1.13) | 0.0818 | 1.20 (1.01 - 1.44) | 0.0406 | 0.98 (0.92 - 1.04) | 0.4345 | 1.01 (0.98 - 1.04) | 0.3645 |

| Expected primary payer | ||||||||||

| Medicare | 1.31 (1.09 - 1.58) | 0.0047 | 1.16 (1.04 - 1.29) | 0.0086 | 1.33 (0.96 - 1.85) | 0.092 | 1.31 (1.18 - 1.47) | ≤.0001 | 1.27 (1.19 - 1.35) | ≤.0001 |

| Medicaid | 1.36 (1.12 - 1.64) | 0.0017 | 1.14 (1.04 - 1.26) | 0.0069 | 1.30 (0.96 - 1.76) | 0.0921 | 1.26 (1.14 - 1.39) | ≤.0001 | 1.25 (1.18 - 1.32) | ≤.0001 |

| Private | 1.16 (0.97 - 1.39) | 0.0971 | 1.00 (0.89 - 1.12) | 0.9806 | 1.13 (0.82 - 1.54) | 0.4652 | 1.15 (1.05 - 1.27) | 0.004 | 1.1 (1.03 - 1.17) | 0.0037 |

| Other Pay | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Disposition Status | ||||||||||

| Routine | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| SNF/ICF/other | 1.11 (1.01 - 1.22) | 0.025 | 1.09 (1.00 - 1.18) | 0.0467 | 1.23 (0.95 - 1.59) | 0.1107 | 0.95 (0.87 - 1.03) | 0.222 | 1.08 (1.04 - 1.13) | 0.0003 |

| Home Health care | 1.10 (1.01 - 1.20) | 0.0295 | 1.21 (1.12 - 1.31) | ≤.0001 | 1.10 (0.86 - 1.41) | 0.4546 | 1.05 (0.97 - 1.14) | 0.2239 | 1.14 (1.10 - 1.19) | ≤.0001 |

| Hospital bed-size | ||||||||||

| Small | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Medium | 1.05 (0.94 - 1.16) | 0.3914 | 1.12 (1.02 - 1.22) | 0.0158 | 0.98 (0.72 - 1.33) | 0.873 | 1.00 (0.92 - 1.09) | 0.9907 | 1.07 (1.02 - 1.12) | 0.0076 |

| Large | 1.07 (0.97 - 1.18) | 0.1807 | 1.07 (0.99 - 1.17) | 0.0919 | 1.01 (0.77 - 1.32) | 0.965 | 1.02 (0.93 - 1.10) | 0.717 | 1.07 (1.02 - 1.12) | 0.0049 |

| Ownership of hospital | ||||||||||

| Government | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Private, not-profit | 1.04 (0.92 - 1.18) | 0.5253 | 1.00 (0.88 - 1.13) | 0.9546 | 1.04 (0.67 - 1.62) | 0.864 | 1.16 (1.04 - 1.31) | 0.0108 | 1.07 (1.01 - 1.15) | 0.0337 |

| Private, invest-own | 1.02 (0.90 - 1.17) | 0.7262 | 1.02 (0.89 - 1.17) | 0.7457 | 1.15 (0.72 - 1.83) | 0.5695 | 1.13 (1.00 - 1.28) | 0.0511 | 1.07 (1.00 - 1.15) | 0.0542 |

| Hospital Location/teaching status | ||||||||||

| Non-metropolitan hospital | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Metropolitan non-teaching | 1.08 (0.98 - 1.20) | 0.1324 | 0.97 (0.89 - 1.05) | 0.444 | 0.89 (0.71 - 1.11) | 0.3002 | 1.00 (0.91 - 1.09) | 0.9721 | 0.99 (0.94 - 1.04) | 0.607 |

| Metropolitan teaching | 1.19 (1.04 - 1.36) | 0.0098 | 1.05 (0.94 - 1.17) | 0.3803 | 0.92 (0.66 - 1.30) | 0.6445 | 1.05 (0.94 - 1.18) | 0.3863 | 1.06 (0.99 - 1.13) | 0.0981 |

| Cirrhosis | 1.13 (1.03 - 1.24) | 0.0116 | 1.19 (1.11 - 1.28) | ≤.0001 | 0.96 (0.78 - 1.19) | 0.7226 | 1.07 (0.99 - 1.17) | 0.0979 | 1.1 (1.05 - 1.14) | ≤.0001 |

| Ascites | 1.46 (1.36 - 1.56) | ≤.0001 | 1.49 (1.39 - 1.61) | ≤.0001 | 1.67 (1.36 - 2.06) | ≤.0001 | 1.58 (1.49 - 1.69) | ≤.0001 | 1.56 (1.51 - 1.62) | ≤.0001 |

| Variceal hemorrhage | 1.04 (0.96 - 1.13) | 0.3709 | 1.03 (0.96 - 1.11) | 0.4609 | 0.96 (0.76 - 1.2) | 0.711 | 0.85 (0.8 - 0.9) | ≤.0001 | 0.98 (0.95 - 1.02) | 0.298 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 1.19 (1.11 - 1.28) | ≤.0001 | 1.18 (1.09 - 1.27) | ≤.0001 | 1.38 (1.12 - 1.69) | 0.0022 | 1.13 (1.06 - 1.2) | 0.0001 | 1.23 (1.19 - 1.27) | ≤.0001 |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | 0.98 (0.82 - 1.17) | 0.8193 | 0.93 (0.76 - 1.14) | 0.4837 | 0.65 (0.36 - 1.19) | 0.1656 | 1.11 (0.98 - 1.26) | 0.0884 | 1.03 (0.94 - 1.12) | 0.552 |

| HCC | 1.02 (0.89 - 1.16) | 0.8114 | 1.15 (1.05 - 1.26) | 0.0023 | 1.13 (0.9 - 1.42) | 0.3001 | 0.94 (0.79 - 1.11) | 0.474 | 1.13 (1.07 - 1.19) | ≤.0001 |

| Acute kidney injury | 1.15 (1.07 - 1.24) | 0.0001 | 1.08 (1.01 - 1.15) | 0.0243 | 1.13 (0.93 - 1.35) | 0.214 | 1.19 (1.11 - 1.27) | ≤.0001 | 1.12 (1.08 - 1.15) | ≤.0001 |

| Cellulitis | 0.99 (0.88 - 1.11) | 0.8073 | 0.94 (0.87 - 1.02) | 0.1399 | 0.83 (0.58 - 1.19) | 0.3029 | 1.04 (0.93 - 1.17) | 0.4881 | 0.94 (0.9 - 0.99) | 0.0242 |

| Peritonitis | 0.87 (0.73 - 1.04) | 0.1145 | 1.1 (0.94 - 1.28) | 0.233 | 0.99 (0.65 - 1.51) | 0.9716 | 1.12 (1.01 - 1.25) | 0.0369 | 1.06 (0.99 - 1.14) | 0.0882 |

| Sepsis | 0.88 (0.81 - 0.96) | 0.0029 | 0.99 (0.93 - 1.06) | 0.8529 | 1 (0.82 - 1.2) | 0.9602 | 0.87 (0.81 - 0.95) | 0.0013 | 0.9 (0.87 - 0.94) | ≤.0001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1.03 (0.94 - 1.12) | 0.5694 | 1.08 (1.01 - 1.16) | 0.0207 | 1.08 (0.87 - 1.35) | 0.4851 | 0.95 (0.87 - 1.02) | 0.1564 | 1.03 (0.99 - 1.07) | 0.1587 |

| Hypertension | 0.95 (0.88 - 1.03) | 0.2257 | 0.93 (0.88 - 0.99) | 0.0217 | 0.87 (0.71 - 1.06) | 0.1618 | 0.94 (0.88 - 1) | 0.0534 | 0.94 (0.91 - 0.97) | ≤.0001 |

| Diabetes | 0.91 (0.85 - 0.98) | 0.0109 | 1.02 (0.96 - 1.09) | 0.5628 | 1 (0.82 - 1.22) | 0.978 | 1.06 (0.98 - 1.14) | 0.1422 | 1 (0.97 - 1.03) | 0.8537 |

| Obesity | 0.88 (0.81 - 0.95) | 0.0019 | 0.95 (0.87 - 1.03) | 0.2087 | 0.64 (0.48 - 0.85) | 0.002 | 0.98 (0.9 - 1.07) | 0.6476 | 0.9 (0.86 - 0.93) | ≤.0001 |

| Pneumonia | 1 (0.91 - 1.1) | 0.938 | 0.95 (0.88 - 1.03) | 0.1867 | 0.96 (0.76 - 1.21) | 0.7353 | 0.96 (0.87 - 1.06) | 0.3671 | 0.95 (0.91 - 1) | 0.0303 |

| ECI | 1.07 (1.05 - 1.09) | ≤.0001 | 1.08 (1.07 - 1.1) | ≤.0001 | 1.11 (1.05 - 1.16) | ≤.0001 | 1.04 (1.02 - 1.06) | 0.0005 | 1.07 (1.06 - 1.08) | ≤.0001 |

HR, Hazard Ratio; CI, confidence interval; ECI, Elixhauser Comorbidity Index.

Demographic variables associated with increased risk of readmission included age 18–74 years compared with ≥75 years for NAFLD and age 18–64 for ALD while male gender was found only among HBV patients. Baseline discharge characteristics predictive of 30-day readmission included being on Medicare and Medicaid insurance compared to other pay for NAFLD, HCV, and ALD; discharged to a skilled nursing facility (SNF) or home health care for NAFLD and home health care for HCV; non-profit private hospital compared to a government hospital for ALD, and metropolitan hospital compared to rural hospital for NAFLD.

In addition to ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and higher number of coexisting comorbidities, comorbidities associated with higher risk of readmission included cirrhosis for NAFLD and HCV; acute kidney injury for NAFLD, HCV, and ALD; HCC for HCV, and peritonitis for ALD. Of note, sepsis was not an independent risk factor for readmission across all liver diseases in our multivariable model although it is the second reason for readmission, indicating that the effect of sepsis on readmission was mediated by a range of comorbidities.

Among NAFLD, males between the ages of 18–64 were at higher risk for readmissions while females age 45–74 were at higher risk for readmissions compared to those 75 years and older. Females were at a 24 and 17% higher risk of having cirrhosis and acute kidney injury separately when readmitted whereas males did not experience a similar risk. (Supplementary Table 4).

3.5Reasons and timing of 30-day readmission by CLD in 2017Cirrhosis and cirrhosis-related complications accounted for 61.6% of readmission for ALD, 30.9% for NAFLD, 30.2% for HCV, and 26.9% for HBV (Table 5). The first most common reason by CLD was hepatic encephalopathy (14.2%) for NAFLD; cirrhosis for ALD (24.3%), sepsis for HCV (13.2%) and HBV (10.9%). The second most common reason by CLD was sepsis for NAFLD (12.3%), cirrhosis for HCV (10.0%), Hepatic encephalopathy for HBV (7.7%), and ascites for ALD (23.9%). However, discordance between index admission (first discharge) and readmission primary diagnosis showed that a large proportion of patients (43.7% for NAFLD; 28.4% for HCV, 39.0% for HBV, and 29.1%) were readmitted for extrahepatic reasons. (Supplementary Fig. 1)

Reasons for 30-Day Readmissions After Discharged with NAFLD, HCV, HBV, or ALD.

| NAFLD | HCV | HBV | ALD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cirrhosis | 10.09 (8.96 - 11.22) | 10.04 (9.2 - 10.88) | 6.82 (4.96 - 8.68) | 24.33 (23.06 - 25.6) |

| Ascites* | 1.83 (1.47 - 2.2) | 5.83 (5.15 - 6.5) | 3.03 (1.67 - 4.39) | 23.94 (22.73 - 25.15) |

| Variceal hemorrhage* | 2.76 (2.25 - 3.28) | 2.83 (2.38 - 3.29) | 2.54 (1.34 - 3.75) | 3.41 (2.89 - 3.93) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy* | 14.19 (13.01 - 15.37) | 8.08 (7.32 - 8.84) | 7.71 (5.08 - 10.34) | 8 (7.26 - 8.75) |

| Hepatorenal syndrome* | 0.68 (0.44 - 0.92) | 0.65 (0.43 - 0.87) | 1.38 (0.26 - 2.49) | 1.37 (1.06 - 1.67) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma* | 1.34 (0.94 - 1.74) | 2.73 (2.23 - 3.22) | 5.39 (3.6 - 7.18) | 0.52 (0.32 - 0.73) |

| Sepsis | 12.27 (11.17 - 13.38) | 13.22 (12.22 - 14.21) | 10.88 (8.55 - 13.22) | 11.6 (10.65 - 12.55) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 5.13 (4.41 - 5.84) | 3.68 (3.21 - 4.15) | 3.3 (1.91 - 4.7) | 1.72 (1.37 - 2.07) |

| Acute kidney injury | 4.95 (4.31 - 5.58) | 2.94 (2.48 - 3.41) | 2.61 (1.48 - 3.74) | 2.72 (2.27 - 3.17) |

| Hypertension | 3.03 (2.44 - 3.63) | 2.29 (1.9 - 2.69) | 1.55 (0.71 - 2.4) | 1.09 (0.81 - 1.37) |

| Pneumonia | 1.67 (1.21 - 2.13) | 1.92 (1.56 - 2.28) | 2.52 (1.35 - 3.69) | 0.96 (0.71 - 1.22) |

| Cellulitis | 1.65 (1.26 - 2.04) | 3.74 (3.21 - 4.27) | 1.7 (0.78 - 2.63) | 1.04 (0.78 - 1.3) |

| Diabetes | 1.34 (0.96 - 1.72) | 1.62 (1.28 - 1.96) | 1.32 (0.45 - 2.19) | 0.69 (0.47 - 0.91) |

| COPD | 1.31 (0.92 - 1.71) | 1.89 (1.5 - 2.28) | 1.16 (0.37 - 1.95) | 0.68 (0.48 - 0.88) |

| Peritonitis | 0.8 (0.53 - 1.07) | 0.88 (0.64 - 1.13) | 0.48 (0.01 - 0.96) | 1.58 (1.18 - 1.97) |

| Alcohol use disorder⁎⁎ | 8.66 (7.87 - 9.45) | 3.79 (2.46 - 5.13) | 36.25 (34.89 - 37.6) |

COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Among NAFLD, there were a few notable differences in readmission reasons by sex where males were more likely to be readmitted for ascites, HCC, or acute kidney injury. (Supplementary Table 5).

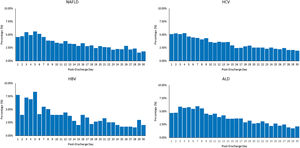

Among patients readmitted within 30 days, the median time to readmission was 12 days for NAFLD, 12 days for HCV, 8 days for HBV, and 10 days for ALD (Fig. 2). A disproportionately high number of 30 day-readmissions occurred during days 1-15 (62.8% for NAFLD, 63.7% for HCV, 74.3% for HBV, and 72.9% for ALD). The overall pattern of reasons for readmission was largely similar over time across all CLDs; however, cirrhosis and cirrhosis-related complications were more common within the first 2 weeks after discharge compared to 15 to 20 days after discharge (Supplementary Tables 6–9).

3.6Comparison of cost and in-hospital mortality between ≤30-day and >30-day among readmitted patientsAmong readmitted patients, substantial differences in cost between ≤30-day readmission and >30-day readmission were observed ($16,986 vs. $14,648 for NAFLD; $16,590 vs. $15,036 for HCV; and $19,152 vs. $16,487 for HBV; and $17,351 vs. $15,114 for ALD). Even after demographic, hospital, and comorbidity adjusted GLMs, the differences remained significant among NAFLD (+5.69% change, 95% CI, 2.54 to 8.93%) and HCV patients (+9.85% change, 6.96 to 12.82%) while no longer significant among ALD and HBV patients (Supplementary Table 10).

Among readmitted patients, substantial differences in in-hospital mortality between ≤30-day readmission and >30-day readmission were observed (8.2% vs. 5.2% for NAFLD; 7.4% vs. 4.3% for HCV; 9.2% vs. 7.0% for HBV; and 8.5% vs. 6.3% for ALD). After controlling for patient's demographic, hospital-level and clinical characteristics, patients with NAFLD and patients with ALD readmitted ≤30 days had increased risk of dying in the hospital compared to those readmitted >30 days (NAFLD Odds ratio [OR]=1.58, 95% CI, 1.28-1.95); ALD OR=1.31, 95%CI: 1.08-1.59) (Supplementary Table 11).

4DiscussionOur analysis showed that the number of patients with CLD discharged from hospitals increased over 50% from 63,204 in 2010 to 125,019 in 2017 consistent with a recent study [17]. On the other hand, the 30-days readmission rate for CLD decreased over the same period except for those with NAFLD which saw a significant increase.

In fact, in our models for determining CLD risk for 30-day readmission, patients with ALD, NAFLD or HCV had a 36%, 23% and 8% (respectively) increased risk after accounting for age, sex, disposition status, primary payor, and hospital characteristics. However, only those with NAFLD remained at an 6% higher risk when additional variables were controlled for including co-morbidity status and the most likely reasons for readmission. On the other hand, having HBV was not found to be associated with readmission.

Our finding for NAFLD being an independent risk factor for 30-day readmission confirms findings from prior studies which also demonstrated that NAFLD can play a significant role in being readmitted especially in the presence of cirrhosis complications (discussed in more detail below) [29–33]. Such findings demonstrate the complexity of NAFLD given that it is a disease associated with older age and multiple metabolic comorbidities. In fact, we found that those with NAFLD had a higher ECI, were less frequently discharged home, and if discharged home, more frequently required home health care when compared to the other CLD's. Furthermore, those with NAFLD had the shortest length of stay which may be driven in part by also having the highest rate of Medicare insurance where among NAFLD patients, they were 31% more likely to be readmitted on Medicare and 36% more likely if receiving Medicaid. They were also 11% more likely to be readmitted if discharged to a skilled nursing facility rather than home.

Furthermore, when we examined 30-day readmission predictors based on patients’ baseline discharge across all CLD's, we found similar findings in that those with ALD or HCV who obtained their insurance coverage through Medicare or Medicaid were more likely to be readmitted within 30-days. For those with HCV who were discharged with home health care, we also found were more likely to be readmitted within 30-days while place of care received for those with ALD (non-profit hospital) or NAFLD (metropolitan hospital) were more likely to be readmitted within 30-days.

Reasons for being readmitted also varied across the liver diseases; however, cirrhosis and cirrhosis complications accounted for approximately 30% of readmissions for NAFLD, HCV, and HBV but over 60% of readmissions for ALD. In addition, among those who were discharged with HBV or HCV and readmitted in 30 days, the most common reason was sepsis which accounted for over 10% of readmissions. Hepatic encephalopathy which accounted for almost 15% of readmissions was the most common reason for those with NAFLD, while cirrhosis, which accounted for a quarter of readmissions, was the most common for those with ALD. Most importantly, among patients readmitted within 30 days, the median time to readmission across all CLDs was 12 days or less which was driven by cirrhosis and cirrhosis complications. For those admitted between days 15 and 30, reasons for readmission varied but were mainly driven by extrahepatic events.

Early readmission (30 days or less) was also associated with an increased risk of death, but only for those patients with NAFLD or HCV even after clinical comorbidities adjustments. Approximately 8% of those with NAFLD and 7% of those with HCV died as an inpatient if readmitted in 30 days or less compared to 5% and 4%, respectively, if readmitted greater than 30 days. In fact, if readmitted in 30 days or less, those with either NAFLD or HCV were at a 58% and 31% higher risk of dying when controlling for other factors. Although approximately 9% of patients with HBV and ALD died when readmitted in less than 30 days, early readmission for HBV or ALD was not independently associated with increased mortality.

Being readmitted was also costly. Across the different types of CLDs, patients averaged almost two readmissions at a weighted cost of $27,688 per admission for a total cost of 6.22 billion dollars over the course of the study. When we adjusted for variables known to be associated with increased costs, being readmitted within 30 days compared to after 30 days increased costs between 8% and 17% [29]. When we investigated cost by specific type of CLD, we found that HBV was associated with the highest cost followed closely by ALD, then HCV, and then NAFLD. However, it was only NAFLD and HCV that were associated with increased costs for being readmitted within 30 days when clinical comorbidities were adjusted for.

Finally, since we found a significant sex difference amongst patients with NAFLD, we performed a subgroup analysis by sex for this cohort of patients. Although many of the findings remain the same as noted above, there are some significant differences that warrant briefly mentioning. Females aged 45–74 were more likely to be readmitted while males aged 18-64 were more likely. Females were more likely to be admitted if on Medicaid or if not discharged to home without support. Males were more likely to be readmitted if receiving Medicare and for ascites, HCC, and AKI. Interestingly, although, NAFLD has been linked with chronic kidney disease, this is one of the first instances where NAFLD has been found to be associated with AKI. However, we suggest that AKI may be the result of decompensated cirrhosis. Nonetheless, such findings highlight the need for potentially longer hospital observation for those with NAFLD given their multiple risk factors for kidney damage and the complexity of their disease which is also seen by the discordance of admission and readmission reasons.

Together, these factors suggest that as the value of care continues to be implemented, hospitals need to balance the interaction between efficiently discharging patients and readmission within 30 days, especially for those with cirrhosis. Our results also suggest that any interventional program developed for CLD readmissions needs to be broad in scope using the tenets of Medicare's Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) [5,34]. In addition, the use of palliative care services, where appropriate, has been shown to be beneficial in reducing hospital utilization and improving patients’ quality of life [35–37]. Furthermore, given that almost one out of every four patients or one out of three patients for those with HCV received Medicaid, the expansion of Medicaid services within states who have not expanded their services may be a potential intervention as well [38]

4.1LimitationsGiven that we used administrative claims data, detailed clinical data such as radiographic, physiologic, and laboratory parameters beyond ICD codes, are not available. To minimize the possibility of the existence of unmeasured confounders, we include comorbidity index in our multivariable model. We are unable to capture cause-specific death such as cardiac- and liver-specific, a clearly important end point. The NRD data is limited to 1 year of historical discharge data so it's not possible to track patients’ records over years. Thus, we are unable to evaluate a full calendar year of index admissions due to the lack of data for January readmissions for patients who were admitted in December. Due to reliance on diagnostic coding to identify CLD, there could be under or over-coding of the data. However, given these coding errors could go in either direction, any miscoding became balanced. Our extended definition of NAFLD may have led to an overestimation, but NAFLD defined by ICD 10 codes of K76.0 and K75.81 underestimates the true NAFLD prevalence. Changes in coding and the data structure of the NRD in 2015 could lead to misclassification bias and trends in some outcomes. In addition, this analysis used data from 2017 and since then the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly shifted the landscape for those with CLD, especially for those with NAFLD and ALD. Not only was the presence of CLD and NAFLD associated with a higher inpatient mortality among patients with COVID-19, but the age standardized mortality rates (ASMR) for those with ALD and NAFLD were found to have increased significantly where much of the increase was not associated with the COVID-19 disease. This increase in ASMR was most apparent among the young non-Hispanic whites and Alaska Indians and Native Americans [39–41]. As such, the increasing readmission we noted in this study have most likely accelerated which will need to be controlled for in future readmission investigations as well as recognizing that adherence to recommended monitoring and follow up for patients with CLD needs to be prioritized as we enter into the COVID-19 recovery phase. Despite these limitations, we used a nationally representative sample of patients and robust statistical methods to decrease potential bias and enhance the generalizability of our findings.

5ConclusionsPatients with CLD experience a number of readmissions although proportionately we found a downward trend for readmissions from 2010 to 2017. The main reasons for readmissions were driven by complications of decompensated cirrhosis, especially ascites and hepatic encephalopathy. However, only NAFLD was found to be an independent risk factor for readmissions among the CLD studied while both HCV and NAFLD were independently associated with increased mortality and costs. Among those with NAFLD, younger males and older females with cirrhosis complications and on government sponsored insurance appeared to be the main drivers of readmission. Therefore, those with CLD but especially NAFLD need transition care programs to address their dispersed needs.

Author contributionsJames M. Paik: study design, statistical analysis, data interpretation, manuscript writing and critical revision and editing; Katherine E Eberly- critical revision and editing; Khaled Kabbara- critical revision and editing; Michael Harring- critical revision and editing; Youssef Younossi- critical revision and editing; Linda Henry- data interpretation, manuscript writing and critical revision and editing; Manisha Verma- critical revision and editing; Zobair M. Younossi- supervision, study design, data interpretation, manuscript writing and critical revision and editing. Guarantor of the article: Dr. Zobair M. Younossi accepts full responsibility for the conduct of the study. He had access to the data and had control of the decision to publish.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Supplementary Fig. 1. Concordance between Index Admission Diagnosis (First Discharge) and 30-day Readmission Diagnosis