Background. Liver disease continues to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality in sub-Saharan Africa, including Nigeria, due to the high endemicity of viral hepatitis B. However non-alcoholic fatty liver disease may be an important contributory factor. The impact of fatty liver disease in our region has not been evaluated.

AIM. To determine the prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) among a population of diabetic (DM) subjects attending the endocrine clinic of LASUTH compared with non-diabetic subjects; ascertain other contributing factors and compare the occurrence of the metabolic syndrome in subjects with and without NAFLD.

Methodology. Consecutive patients who satisfy the study criteria were enrolled. An investigator-administered questionnaire was used to determine symptoms of liver disease, followed by physical examination to obtain anthropometric indices as well as signs of liver disease. Abdominal scan was performed to determine radiologic evidence of fatty liver and fasting blood samples were collected from for the measurement of fasting lipid profile, glucose, liver biochemistry and serology for hepatitis B and C markers.

Results. One hundred and fifty subjects, mean age 56years (standard deviation = 9, range 20-80 yr) and gender ratio (F: M) of 83:67(55%:45%), were recruited. 106 were diabetics and 44 non-diabetics. The overall prevalence of NAFLD amongst all study subjects was 8.7%. The prevalence rate of NAFLD was higher in the DM cases than in the Control subjects but this difference was not statistically significant (9.5 vs. 4.5%, p = 0.2). Only one of the subjects with fatty liver disease had elevated transaminase levels (steatohepatitis) and also had type 2 DM. Central obesity as measured by waist circumference (WC) and SGPT levels were significantly higher in people with fatty liver. The mean body mass index (BMI) of diabetic and non-diabetic patients was similar (31 vs. 30 kg/m2). The prevalence of the metabolic syndrome was higher in the subjects with NAFLD than in those without fatty liver disease but this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.8).

Conclusion. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is present in Africa but is less than what one would expect based on American and European studies.

Fatty liver is a spectrum of disorders defined by abnormal accumulation of triglycerides in the liver; and ranges from fatty liver alone (steatosis) to fatty liver with inflammation (steatohepatitis).1 It can occur with use of alcohol (alcohol-related fatty liver) or in the absence of alcohol (non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). NAFLD is strongly associated with epidemic of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM).2 Diabetes mellitus is a chronic disorder that is associated with cardiovascular complications of which the metabolic syndrome (Mets) plays a prominent role.3 The metabolic syndrome (Mets) is a cluster of cardiovascular risk factors that is characterized by obesity, central obesity, insulin resistance, atherogenic dyslipidemia, and hypertension.4 The prevalence of the Mets in the general population is estimated to be between 17-25%, although a recent report documented a higher prevalence with comparable gender distribution in Nigerian type 2 diabetics.5

NAFLD is the hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome as a strong link has been reported between them particularly among obese adolescent males.6 Initially NAFLD was thought to be benign, but it has been shown to progress to more severe forms of liver disease including cirrhosis and primary liver cell carcinoma (PLCC) especially amongst the biopsy proven cases.7

Clinical manifestation of NAFLD is usually absent or subtle with abnormal aminotransferase or incidental radiographic findings of fatty liver. The pathogenesis is thought to be due to multi-hit process involving insulin resistance, oxidative stress, apoptotic pathways and adipocytokines.8 No definite consensus treatment for NAFLD exist but nonetheless weight reduction, treatment of the components of metabolic syndrome and a number of new agents under various phase of trial have shown a lot of promises.9

The diagnosis is based on establishing the presence of fatty liver as well as the non-alcoholic nature of the disease. A liver biopsy is the gold standard, but it is invasive with associated risk. Sonography is the cheapest of all the imaging modalities and is widely available. Sonographic features include the presence of a bright hepatic echo pattern (compared with the kidneys), deep attenuation, vascular blurring either singly or in combination to diagnose hepatic steatosis. These features have a diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of greater than 82%.10

NAFLD is estimated to affect 20-30% of the population in the United States.9 The impact of NAFLD in our setting is unknown as the background prevalence of hepatic steatosis in the general population has not been established. An earlier report had noted a prevalence rate of 13.3% among a cohort of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected subjects receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).11 The purpose of our study was to determine the prevalence of NAFLD in our diabetic and non-diabetic subjects who attend the endocrine clinic of LASUTH and compare the occurrence of the metabolic syndrome in subjects with and without NAFLD. We also attempted to ascertain other contributing factors (HBV and HCV infection) to liver disease in these subjects.

MethodologyThe study design was a cross sectional study carried out in the endocrine clinic of an urban university teaching hospital in Lagos, Nigeria. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Lagos State University Hospital (LASUTH) before commencement of the study in October 2009. Informed consent was obtained from prospective study patients before enrolment. Consecutive patients who fulfilled study criteria were recruited from October 2009 to August 2010. The diabetic group consisted of type 2 diabetic and obese patients. The non-diabetic control subjects, recruited amongst hospital workers, including students, were sex but not aged matched with the cases.

A questionnaire was administered by the investigators to ascertain symptoms of liver disease, and a thorough physical examination was undertaken to obtain anthropometrics indices as well as seek out signs of liver disease if any in them. A ten millilitres sample of fasting blood was collected for the measurement of fasting lipid profile, glucose, liver biochemistry and serology for hepatitis B and C markers. All biochemistry assays were run on an automated system (Human start 80-clinical chemistry analyzer). The principle of the assay of alanine transaminase was by measuring enzyme activity using the kinetic method as per the recommendation of the international federation of clinical chemistry.12 Serology for viral markers was done using the immunocomb kit. Excluded patients included those known to be alcoholic, patients suffering from malignancy, patients receiving a form of chemotherapy or corticosteroids, patients with significant co morbid medical conditions including congestive heart failure, chronic renal dysfunction, chronic pulmonary disease, psychiatric disease and those patients unable/unwilling to provide informed consent/participate.

Fasting blood samples were taken for the determination of 4 parameters of the lipid profile viz total cholesterol (TCHOL), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and triglyceride (TG). Total cholesterol assay was done using a modified method of Liebermann-Burchard,13 HDL-cholesterol by precipitation method14 and TG was estimated using a kit employing enzymatic hydrolysis of TG with lipases.15 LDL-C was calculated using the Friedwald’s formula16 LDL = (TCHOL -HDL-C)-TG/5 when the values of TG were less than 400 mg%.

The enrolled patients underwent an upper abdominal ultrasound (US) scan after an overnight fast. All US scan were performed by an experienced radiologist using a 3.5MHz probe of a Mindray DP 9900 Plus Ultrasound scanning machine looking for radiologic evidence of hepatic steatosis.

Study Definitions- 1.

The presence of the metabolic syndrome was determined using the new definition.3 The presence of three or more of any of the following is a pointer to the Mets. waist circumference (WC) greater than 102 cm in men and 88 cm in women; serum triglycerides (TG) level of at least 150 mg/ dL (1.69 mmol/L); high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) level of less than 40 mg/dL (1.04 mmol/L) in men and 50 mg/dL (1.29 mmol/ L) in women; blood pressure of at least 130/85 mmHg.

- 2.

Significant alcohol consumption means alcohol consumption, estimated by questionnaire of > 40 gram/week.17

- 3.

Fatty liver disease is said to be present if the following Sonographic features were present either singly or in combination: the presence of a bright hepatic echo pattern (compared with the kidneys), deep attenuation and vascular blurring.10

- 4.

The criteria for diagnosing DM is based on two abnormal glucose values with or without symptoms of hyperglycemia: Fasting plasma glucose of ≥ 126 mg%, random plasma glucose ≥ 200 mg%.18

The intra-assay CVs for cholesterol, TG and glucose were 2.36%, 3.45% and 1.63% and the inter-assay CVs were 1.14%, 2.89% and 1.33% respectively. The coefficients of variation intra-assay of the other parameters are Alt (20-32%), AST (15-20%), and ALP (10-15%).

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics were used to analyze the collected data. Analytic statistical methods employed included the Student t test to compare continuous variables and the Chi-Square test to compare categorical variables. The alpha level of significance (i.e. p value) was set at 0.05. All statistical tests were performed using the computer statistical software package SPSS version 17 (SPSS Inc, Chicago IL).

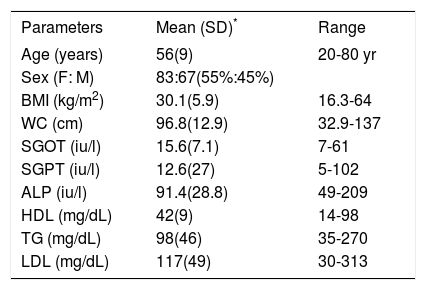

ResultsDemographics and biochemical profile of subjectsThe basic demographics and biochemical profile of the enrolled subjects are shown in table 1.

Demographics and biochemical profiles of the study subjects.

| Parameters | Mean (SD)* | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 56(9) | 20-80 yr |

| Sex (F: M) | 83:67(55%:45%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.1(5.9) | 16.3-64 |

| WC (cm) | 96.8(12.9) | 32.9-137 |

| SGOT (iu/l) | 15.6(7.1) | 7-61 |

| SGPT (iu/l) | 12.6(27) | 5-102 |

| ALP (iu/l) | 91.4(28.8) | 49-209 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 42(9) | 14-98 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 98(46) | 35-270 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 117(49) | 30-313 |

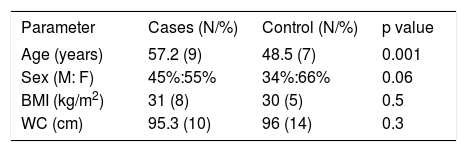

A comparison of the clinical parameters between the DM and non-DM patients showed that clinical parameters (other than the age); were comparable. The DM patients were significantly older than the Controls (Table 2).

Comparison of clinical parameters between DM cases and controls.

| Parameter | Cases (N/%) | Control (N/%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 57.2 (9) | 48.5 (7) | 0.001 |

| Sex (M: F) | 45%:55% | 34%:66% | 0.06 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31 (8) | 30 (5) | 0.5 |

| WC (cm) | 95.3 (10) | 96 (14) | 0.3 |

Duration of DM: mean 7.4 years (SD 9.2), Range 0.1 to 30 years.

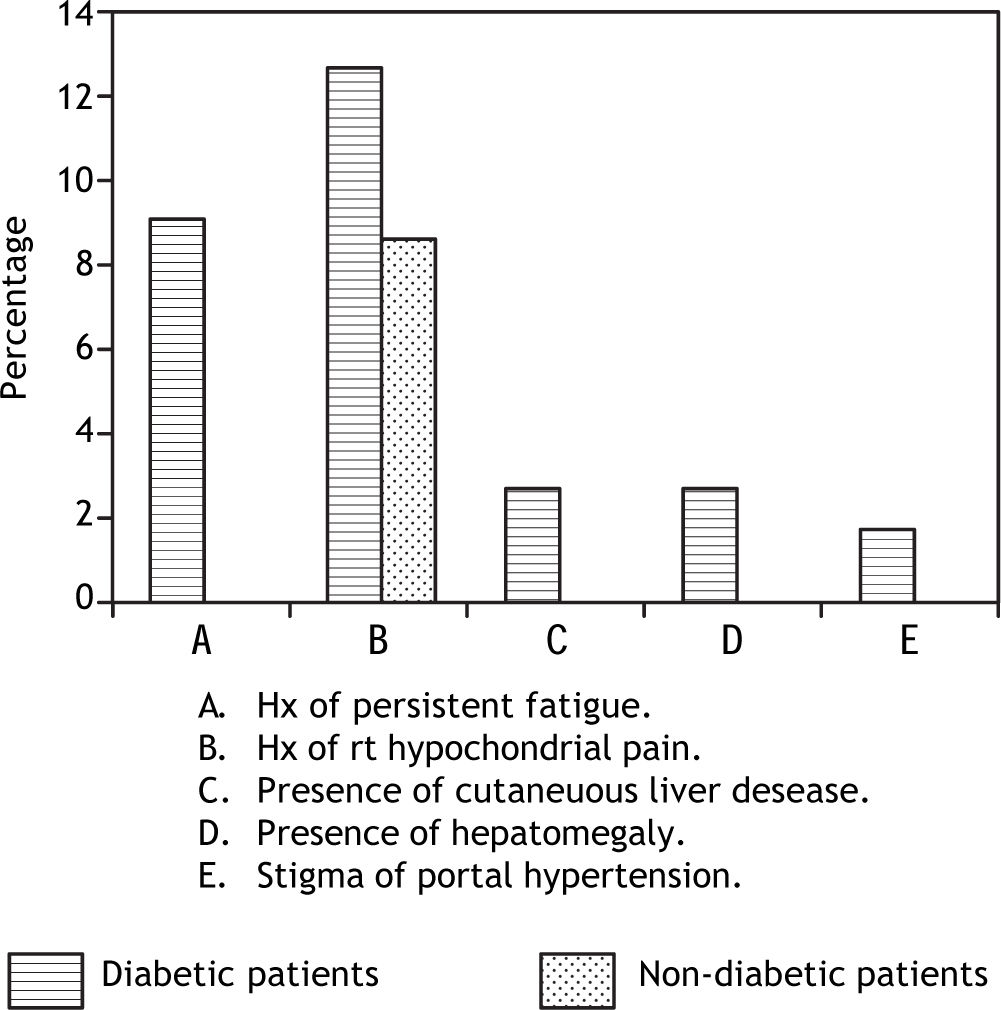

The symptoms of liver disease as shown in Figure 1 were present more in the non-diabetic patients than the diabetic patients. The cutaneous stigma of chronic liver disease, including hepatomegaly and stigma of portal hypertension were present in 7(6.4%), 3(2.8%) and 2(1.8%). A history of blood transfusion was noted in 7 (6.4%) of the subjects (all diabetics). There was no documented history of ingestion of hepatotoxic drug usage (amiodarone, HAART & tamoxifen) while a history of previous jaundice was noted in 2 subjects (diabetic).

Fatty liver diseaseThe overall prevalence of fatty liver among all study subjects was 8.7%. The prevalence rate of NA-FLD was higher in the diabetic cases than in the non-diabetic patients but this difference was not statistically significant (9.5 vs. 4.5%, p = 0.2). Only one of the subjects with fatty liver disease had elevated serum aminotransaminase levels and also had type 2 DM. Fatty liver cases were in the age range 33-70years.

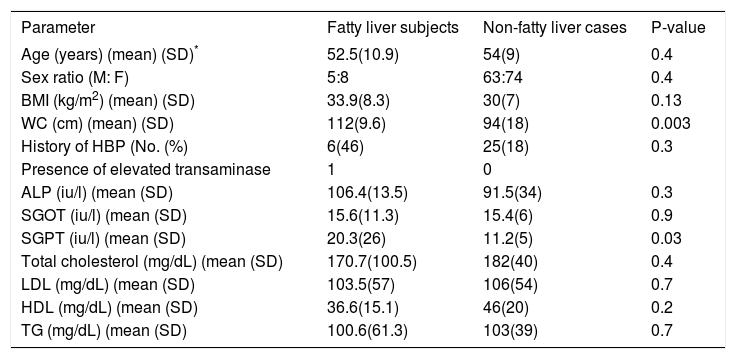

A comparison of the clinical and biochemical parameters of the subjects with fatty liver and those without fatty liver were comparable except for WC and SGPT levels which were significantly higher in people with fatty liver. Hepatitis C antibody was absent in the study subjects. HBsAg positivity was present in 2(4.5%) of the Control subjects but absent in patients with DM. These results are show in Table 3.

Comparison of clinical and biochemical characteristics of subjects with and without fatty liver.

| Parameter | Fatty liver subjects | Non-fatty liver cases | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (mean) (SD)* | 52.5(10.9) | 54(9) | 0.4 |

| Sex ratio (M: F) | 5:8 | 63:74 | 0.4 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (mean) (SD) | 33.9(8.3) | 30(7) | 0.13 |

| WC (cm) (mean) (SD) | 112(9.6) | 94(18) | 0.003 |

| History of HBP (No. (%) | 6(46) | 25(18) | 0.3 |

| Presence of elevated transaminase | 1 | 0 | |

| ALP (iu/l) (mean (SD) | 106.4(13.5) | 91.5(34) | 0.3 |

| SGOT (iu/l) (mean (SD) | 15.6(11.3) | 15.4(6) | 0.9 |

| SGPT (iu/l) (mean (SD) | 20.3(26) | 11.2(5) | 0.03 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) (mean (SD) | 170.7(100.5) | 182(40) | 0.4 |

| LDL (mg/dL) (mean (SD) | 103.5(57) | 106(54) | 0.7 |

| HDL (mg/dL) (mean (SD) | 36.6(15.1) | 46(20) | 0.2 |

| TG (mg/dL) (mean (SD) | 100.6(61.3) | 103(39) | 0.7 |

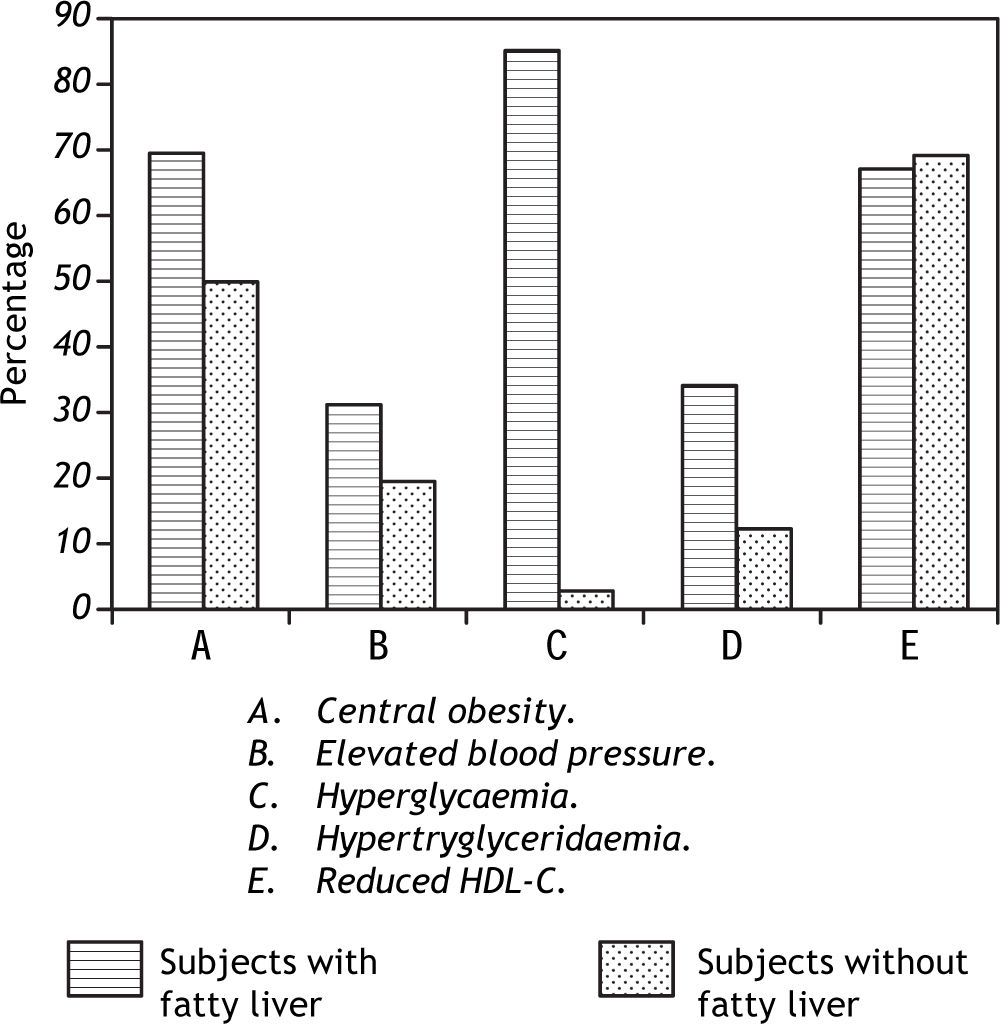

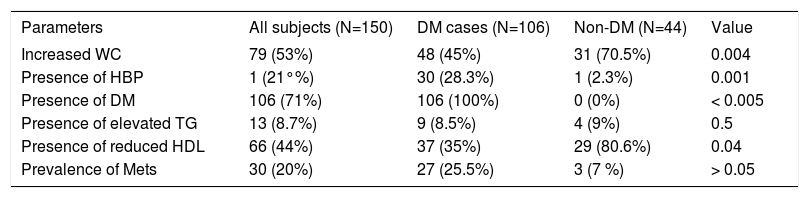

The prevalence of the metabolic syndrome was higher in the subjects with NAFLD than in those without fatty liver disease but this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.8) (Figure 2). Table 4 shows the distribution of the presence of metabolic syndrome defining parameters among the study subjects.

Presence of metabolic syndrome parameters among the study subjects

| Parameters | All subjects (N=150) | DM cases (N=106) | Non-DM (N=44) | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased WC | 79 (53%) | 48 (45%) | 31 (70.5%) | 0.004 |

| Presence of HBP | 1 (21°%) | 30 (28.3%) | 1 (2.3%) | 0.001 |

| Presence of DM | 106 (71%) | 106 (100%) | 0 (0%) | < 0.005 |

| Presence of elevated TG | 13 (8.7%) | 9 (8.5%) | 4 (9%) | 0.5 |

| Presence of reduced HDL | 66 (44%) | 37 (35%) | 29 (80.6%) | 0.04 |

| Prevalence of Mets | 30 (20%) | 27 (25.5%) | 3 (7 %) | > 0.05 |

NAFLD is the hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome and is becoming a major cause of liver morbidity and mortality worldwide. To our knowledge no data on prevalence of this condition in the general population in Nigeria exist. The observed difference in prevalence of fatty liver between diabetics and control (9.5 vs. 4.5%, p = 0.2) was not statistically significant while the overall prevalence of 8.7% appears rather low when compared with findings in other geographical regions; 20-30% in the USA9, Russian federation19 and Japan.20 This may relate to differences in study population as well as diagnostic modality. Earlier report by Richard Guerrero, et al.11 had documented ethnic differences in subjects who had similar risk factors (insulin resistance). In their study African Americans were shown to have less intra-peritoneal fat which correlated with hepatic triglyceride content (HTGC) than visceral fat. This is in keeping with an earlier report by Lesi, et al.11 which showed a lower prevalence of 13.3% among a cohort of HIV- infected patients receiving highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) within the same geographical area. The patients in this study were at increased risk of developing NAFLD due to the adverse effect of HAART. Ultrasonography employed in this study is unable to detect mild fat accumulation (usually less than 30%).10 It is possible that cases of mild steatosis may have been missed in the present study. The presence of fatty liver did not vary with the sex of the subjects while their age range was from 4-7th decade with majority in the 5th decade of life. This is in keeping with earlier observation that NAFLD occurs at all ages with no sex predilection but incidence increases with increasing body size21. Subjects with fatty liver in this study had significantly more central obesity than those without. Also an earlier report22 noted peak incidence around the 5th decade as in the present study.

Most of the subjects with fatty liver had simple steatosis as only one had features of steatohepatitis. The symptomatology noted in this study were fatigue and right hypochondrial pain/discomfort. The low prevalence of NAFLD noted here as well as the milder nature of the disease may suggest a lower disease burden than in the Western world. This may correlate with the observed epidemiology of documented risk factors (obesity and attendant metabolic consequences) of fatty liver which has assumed an epidemic proportion in some western nations.

Also contrary to reports6 in other regions, the observed difference in fatty liver prevalence between subjects with metabolic syndrome and without was not significant. This may relate to the small population size of the subjects. More studies involving larger subjects are required to clarify this. However the subjects with fatty liver had significantly more central obesity, one of the parameters of metabolic syndrome.

There were no other contributory factors (hepatotoxic drug use, viral hepatitis) to liver disease among the study subjects; the two patients who tested positive to hepatitis B were asymptomatic and did not have fatty liver disease. None of the subjects had serologic marker of hepatitis C. The observed prevalence of the markers of these hepatotrophic viruses follows the documented pattern in this region with low prevalence of hepatitis C.

Diagnosis of NAFLD in this study was by ultra-sonography although liver biopsy remains the gold standard. The later is however invasive with a lot of risk and ethically not acceptable for this kind of study. Also establishment of alcohol consumption habit relied on the subjects’ history which may not be accurate. Similar studies recruiting larger subject are required to validate our findings on fatty liver in diabetics and non-diabetic as well as in subjects with and without metabolic syndrome.

ConclusionNon-alcoholic fatty liver is present in Africa but appears to be less than what one would expect based on American and European studies. Although the diagnosis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease appears to be decreased in the Nigerian population, the documented prevalence of fatty liver disease in this study is still clinically significant and is a wake-up call for Nigerian health practitioners and policy makers to be on the alert and also formulate policy to help curtail its impact especially by measures to reduce the components of metabolic syndrome in view of the association. The results of our study should be interpreted with caution given the small sample size and larger studies with an African population are needed.