Introduction. Treatment of genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C in elderly patients has been associated with low rates of a sustained virological response (SVR), but the reasons are unclear. Objective. To determine the SVR rate in patients ≥ 60 years with genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C treated with Peg-IFN and ribavirin, and to identify risk factors related to treatment response in this specific group of patients.

Material and methods. Patients were divided into < 60 years (non-elderly) and >60 years (elderly) and were compard regarding clinical, laboratory and histological characteristics and response to treatment.

Results. A total of 231 patients were included in the study. The elderly group (n=89) presented a predominance of women, more advanced hepatic disease, higher glucose, cholesterol and LDL levels, lower hemoglobin levels, and a larger proportion of overweight subjects. The SVR rate was lower (25 vs. 46%) and anemia, ribavirin dose reduction and use of filgrastim and erythropoietin were more frequent in elderly patients. Negative predictive factors of SVR in the whole group (n = 231) were glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL and age ≥ 60 years. In the elderly group, only pretreatment variables (lower serum glucose and higher hemoglobin levels) were associated with SVR.

Conclusion. The SVR rate was low in elderly patients. However, this poor response was not due to poor tolerance, but mainly to pretreatment conditions. Among elderly patients, the best candidates for hepatitis C treatment are those with elevated pretreatment hemoglobin levels and adequate glycemic control.

Chronic infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) is highly prevalent in many regions of the world. Patients infected with HCV are at an increased risk of developing cirrhosis and hepatocarcinoma, conditions that are responsible for the high rates of morbidity and mortality seen in these patients. The increased life expectancy of the population has led to a significant increase in the prevalence of HCV infection among older adults, reflecting high rates of infection acquired in the past.1 Older age is associated with the progression of liver disease and is an important risk factor for the development of hepatocarcinoma, particularly among patients treated with interferon who do not achieve a sustained virological response (SVR).2

Treatment of elderly patients with pegylated interferon (Peg-IFN) and ribavirin (RBV) is a major challenge since some studies have associated this combination therapy with higher rates of treatment discontinuation due to adverse events,3–4 Peg-IFN and/or RBV dose reductions,5 and lower SVR rates6 when these individuals were compared to younger patients.

Questions remain regarding the treatment of hepatitis C in the elderly population. The SVR rates reported in the literature vary because the series studied are heterogeneous in terms of the therapeutic regimen used (doses and treatment duration) and age classifications.3–7 In addition, few studies have specifically evaluated factors associated with poor treatment response in the elderly population.

Therefore, the objective of the present study was to determine the SVR rate in patients ≥ 60 years with chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 and treated with Peg-IFN and RBV, and to evaluate risk factors related to treatment response in this specific group.

Material and MethodsThe study was conducted at the Hepatitis Outpatient Clinic of Federal University of São Paulo. Patients with chronic hepatitis C (positive for anti-HCV and HCV RNA) infected with genotype 1 and treated with Peg-IFN and RBV between 2005 and 2010 were studied retrospectively. Criteria for inclusion in the study were age older than 18 years, a positive HCV RNA test (quantitative detection by Taq-Man real-time PCR, with a detection limit of 50 IU/mL), histological grade of disease activity ≥ A2 and histological stage of fibrosis ≥ F2 according to the Metavir score, and administration of at least one dose of Peg-IFN and RBV. Patients co-infected with HIV or HBV, patients with alcoholic liver disease, chronic kidney disease and decompensated cirrhosis, and organ transplant recipients were excluded.

The patients were divided into two groups according to age: < 60 years (non-elderly) and ≥ 60 years (elderly). The groups were compared regarding clinical, laboratory and histological characteristics and response to treatment by intention-to-treat analysis.

Pretreatment clinical and laboratory assessmentThe following variables were analyzed: age, gender, risk factors of transmission, serum levels of ALT, hemoglobin, cholesterol, HDL, LDL, triglycerides, glucose and ferritin, body mass index, HCV load, and stage of fibrosis and grade of necroinflammatory activity on liver biopsy.

Therapeutic regimenPeg-IFN was administered subcutaneously at a dose of 180 μg/week (Peg-IFN2a) or 1.5 μg/kg/week (Peg-IFN2b) for 48 weeks. Weight-based RBV was administered orally for 48 weeks at a dose of 1,250 mg/day for patients weighing ≥ 75 kg or of 1,000 mg/ day for patients weighing < 75 kg.

Erythropoietin was introduced when hemoglobin < 10 g/dL or in patients who showed symptoms of anemia. A dose of 10,000 to 40,000 IU per week was administered subcutaneously based on clinical criteria. When granulocytes were < 500/mm3, 300 μg filgrastim was administered subcutaneously 1 or 2 times per week. The Peg-IFN and/or RBV dose was either reduced or discontinued if the changes persisted. Treatment was also discontinued in cases of patients with platelets < 25,000/mm3 and/or clinical intolerance. The SVR to treatment was evaluated 24 weeks after completion of treatment by assessment of HCV RNA.

Clinical and laboratory assessment during treatmentThe following events during treatment were evaluated: treatment discontinuation, Peg-IFN and/or RBV dose reduction, development of anemia (hemoglobin ≤ 10 g/dL), and use of at least one dose of erythropoietin and/or filgrastim.

Statistical analysisThe results are expressed as the mean or median. The χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare proportions between groups. Continuous variables were compared using the t-test or MannWhitney test. A logistic regression model was constructed to identify factors associated with SVR. A P value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

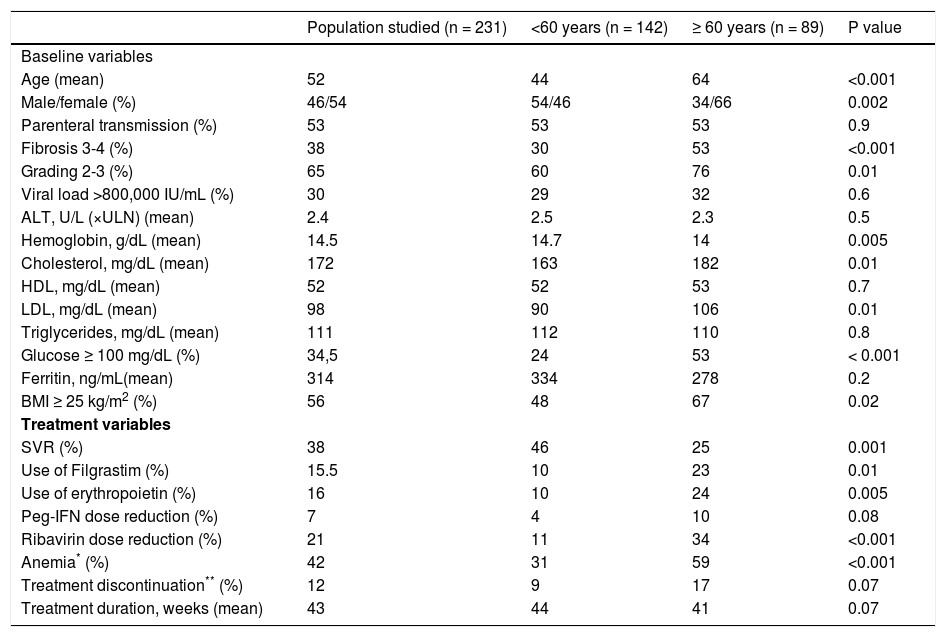

ResultsA total of 231 patients with chronic hepatitis C (genotype 1) who received Peg-IFN and RBV were studied. Comparison of baseline variables between the elderly and non-elderly groups showed a predominance of women, more advanced fibrosis stage (F3-4), higher grade of necroinflammatory activity (A2-3), higher glucose, cholesterol and LDL levels, lower hemoglobin levels, and a larger proportion of overweight subjects in the group of elderly patients. With respect to treatment variables, elderly patients presented a lower SVR rate, a higher frequency of anemia and RBV dose reduction, and more frequent use of filgrastim and erythropoietin. On the other hand, no difference in treatment duration or in the frequency of treatment discontinuation due to side effects was observed between the elderly and non-elderly groups. Table 1 shows the comparison of baseline and treatment characteristics between elderly and non-elderly patients.

Comparison of baseline and treatment characteristics between elderly and non-elderly patients with chronic hepatitis C (genotype 1).

| Population studied (n = 231) | <60 years (n = 142) | ≥ 60 years (n = 89) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline variables | ||||

| Age (mean) | 52 | 44 | 64 | <0.001 |

| Male/female (%) | 46/54 | 54/46 | 34/66 | 0.002 |

| Parenteral transmission (%) | 53 | 53 | 53 | 0.9 |

| Fibrosis 3-4 (%) | 38 | 30 | 53 | <0.001 |

| Grading 2-3 (%) | 65 | 60 | 76 | 0.01 |

| Viral load >800,000 IU/mL (%) | 30 | 29 | 32 | 0.6 |

| ALT, U/L (×ULN) (mean) | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 0.5 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL (mean) | 14.5 | 14.7 | 14 | 0.005 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL (mean) | 172 | 163 | 182 | 0.01 |

| HDL, mg/dL (mean) | 52 | 52 | 53 | 0.7 |

| LDL, mg/dL (mean) | 98 | 90 | 106 | 0.01 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL (mean) | 111 | 112 | 110 | 0.8 |

| Glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL (%) | 34,5 | 24 | 53 | < 0.001 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL(mean) | 314 | 334 | 278 | 0.2 |

| BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (%) | 56 | 48 | 67 | 0.02 |

| Treatment variables | ||||

| SVR (%) | 38 | 46 | 25 | 0.001 |

| Use of Filgrastim (%) | 15.5 | 10 | 23 | 0.01 |

| Use of erythropoietin (%) | 16 | 10 | 24 | 0.005 |

| Peg-IFN dose reduction (%) | 7 | 4 | 10 | 0.08 |

| Ribavirin dose reduction (%) | 21 | 11 | 34 | <0.001 |

| Anemia* (%) | 42 | 31 | 59 | <0.001 |

| Treatment discontinuation** (%) | 12 | 9 | 17 | 0.07 |

| Treatment duration, weeks (mean) | 43 | 44 | 41 | 0.07 |

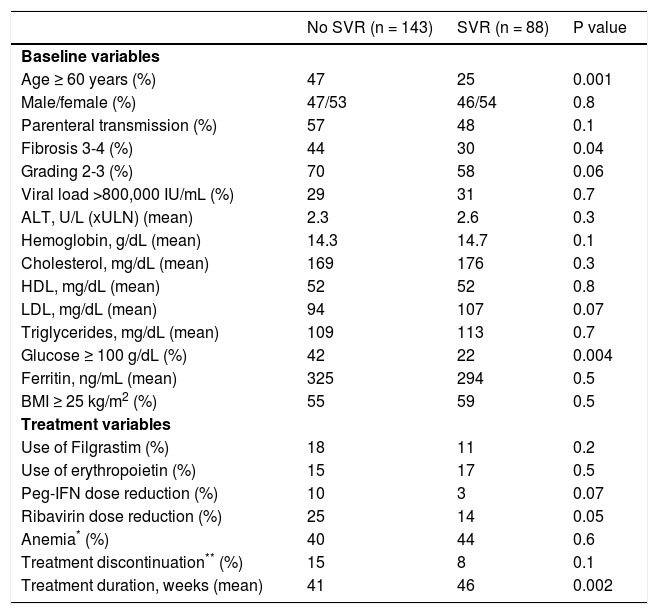

Among patients infected with HCV-1 and treated with Peg-IFN and RBV (n = 231), those who achieved SVR (n = 88) were younger (P = 0.001), presented a lower degree of fibrosis (P = 0.04), a higher frequency of normal glucose levels (P = 0.004), and a longer treatment duration (P = 0.002) (Table 2).

Comparison of baseline and treatment variables in the population studied (n = 231) according to the presence or absence of a sustained virological response (SVR).

| No SVR (n = 143) | SVR (n = 88) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline variables | |||

| Age ≥ 60 years (%) | 47 | 25 | 0.001 |

| Male/female (%) | 47/53 | 46/54 | 0.8 |

| Parenteral transmission (%) | 57 | 48 | 0.1 |

| Fibrosis 3-4 (%) | 44 | 30 | 0.04 |

| Grading 2-3 (%) | 70 | 58 | 0.06 |

| Viral load >800,000 IU/mL (%) | 29 | 31 | 0.7 |

| ALT, U/L (xULN) (mean) | 2.3 | 2.6 | 0.3 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL (mean) | 14.3 | 14.7 | 0.1 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL (mean) | 169 | 176 | 0.3 |

| HDL, mg/dL (mean) | 52 | 52 | 0.8 |

| LDL, mg/dL (mean) | 94 | 107 | 0.07 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL (mean) | 109 | 113 | 0.7 |

| Glucose ≥ 100 g/dL (%) | 42 | 22 | 0.004 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL (mean) | 325 | 294 | 0.5 |

| BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (%) | 55 | 59 | 0.5 |

| Treatment variables | |||

| Use of Filgrastim (%) | 18 | 11 | 0.2 |

| Use of erythropoietin (%) | 15 | 17 | 0.5 |

| Peg-IFN dose reduction (%) | 10 | 3 | 0.07 |

| Ribavirin dose reduction (%) | 25 | 14 | 0.05 |

| Anemia* (%) | 40 | 44 | 0.6 |

| Treatment discontinuation** (%) | 15 | 8 | 0.1 |

| Treatment duration, weeks (mean) | 41 | 46 | 0.002 |

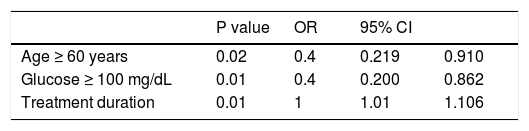

Stepwise forward logistic regression was performed to identify variables that were independently associated with SVR (n = 231). The model included only variables that were significant upon univariate analysis. In the final model, negative predictive factors of SVR were glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL and age ≥ 60 years. Longer treatment duration was a positive predictive factor of SVR (Table 3).

Predictive factors of a sustained virological response in 231 patients infected with HCV-1 and treated with pegylated interferon and ribavirin.

| P value | OR | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥ 60 years | 0.02 | 0.4 | 0.219 | 0.910 |

| Glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL | 0.01 | 0.4 | 0.200 | 0.862 |

| Treatment duration | 0.01 | 1 | 1.01 | 1.106 |

OR: odds ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

Since older age was independently associated with lower SVR, an analysis including only elderly patients was performed in order to identify the variables associated with SVR in this specific group of patients.

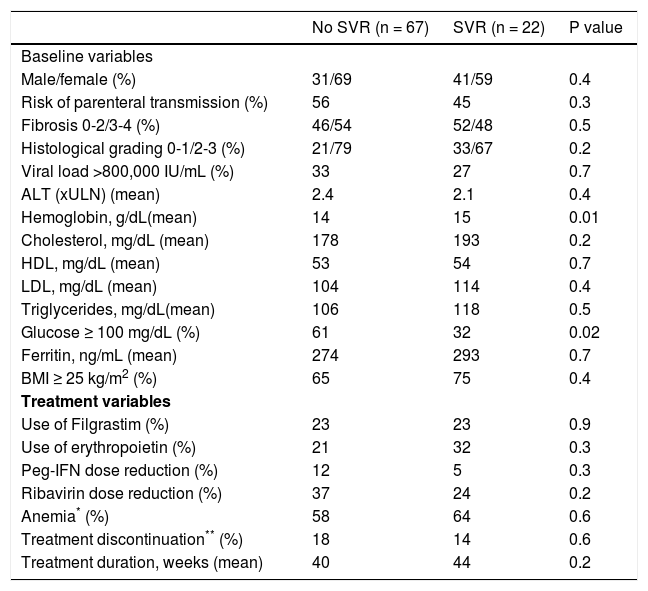

Comparison of baseline and treatment variables in elderly patients according to the presence or absence of SVRLower serum glucose and higher hemoglobin levels were the baseline variables associated with SVR upon univariate analysis in the group of elderly patients. No difference in any of the treatment variables was observed between patients who achieved SVR and those who did not (Table 4).

Comparison of baseline and treatment variables according to the presence or absence of SVR in elderly patients (≥ 60 years) infected with HCV-1 and treated with pegylated interferon and ribavirin (n = 89)

| No SVR (n = 67) | SVR (n = 22) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline variables | |||

| Male/female (%) | 31/69 | 41/59 | 0.4 |

| Risk of parenteral transmission (%) | 56 | 45 | 0.3 |

| Fibrosis 0-2/3-4 (%) | 46/54 | 52/48 | 0.5 |

| Histological grading 0-1/2-3 (%) | 21/79 | 33/67 | 0.2 |

| Viral load >800,000 IU/mL (%) | 33 | 27 | 0.7 |

| ALT (xULN) (mean) | 2.4 | 2.1 | 0.4 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL(mean) | 14 | 15 | 0.01 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL (mean) | 178 | 193 | 0.2 |

| HDL, mg/dL (mean) | 53 | 54 | 0.7 |

| LDL, mg/dL (mean) | 104 | 114 | 0.4 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL(mean) | 106 | 118 | 0.5 |

| Glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL (%) | 61 | 32 | 0.02 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL (mean) | 274 | 293 | 0.7 |

| BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (%) | 65 | 75 | 0.4 |

| Treatment variables | |||

| Use of Filgrastim (%) | 23 | 23 | 0.9 |

| Use of erythropoietin (%) | 21 | 32 | 0.3 |

| Peg-IFN dose reduction (%) | 12 | 5 | 0.3 |

| Ribavirin dose reduction (%) | 37 | 24 | 0.2 |

| Anemia* (%) | 58 | 64 | 0.6 |

| Treatment discontinuation** (%) | 18 | 14 | 0.6 |

| Treatment duration, weeks (mean) | 40 | 44 | 0.2 |

Treatment was discontinued due to side effects by 16.8% of the patients (n = 15). The main side effects were fatigue (8%), anemia (4%), hepatic decompensation (2%), allergy (1%), and vasculitis (1%).

DiscussionChronic hepatitis C is a severe disease that can cause cirrhosis and is associated with high mortality. The cohort of patients who acquired the infection in the past is older today, a fact that renders them more susceptible to advanced liver disease. In addition, these patients are at high risk of developing hepato cellular carcinoma.8–9 Antiviral treatment reduces the risk of these complications and increases the survival of patients with chronic hepatitis C, but is associated with important side effects and low response rates, representing a challenge particularly in this population of older patients.10

The current standard treatment for chronic hepatitis C is Peg-INF and RBV combination therapy, which results in SVR in 40-55% of cases.11–12 However, these results were obtained in large clinical trials in which elderly patients are generally not eligible for study. In the present study evaluating patients with HCV-1 treated with Peg-IFN and RBV, the SVR rate was low (25%) among those > 60 years when compared to younger patients (46%). In fact, analysis of predictive factors of SVR in the population studied showed that age ≥ 60 years was predictive of poor treatment response. Controversy exists whether older age unfavorably affects the response to HCV treatment12. A wide variation in SVR rates among older patients has been reported in the literature (22 to 52%). These discrepant results can be attributed to study heterogeneity, different age limits, and small sample size, among others. Surprisingly, Huang, et al.3 reported an SVR rate of 51.9% in 27 patients older than 65 years with chronic hepatitis C caused by genotype 1 who were treated with Peg-IFN and RBV. In contrast, in the study of Kainuma et al6 the SVR rate was 22.9% in 253 patients aged 65 years or older with chronic hepatitis C treated with Peg-IFN and RBV, a rate similar to that observed in the present study.

The reasons for the poor treatment response among elderly patients are still unclear. Some investigators suggest that treatment with Peg-IFN and RBV is associated with a larger number of clinical and laboratory side effects that are less tolerated by this population, compromising therapeutic efficacy as a result of drug dose reductions and/or early discontinuation of treatment.5–7 The frequency of treatment discontinuation was 16.8% in the elderly patients studied here. Fatigue and anemia were the most frequent adverse events that led to drug discontinuation. In addition, older adults more frequently required RBV dose reductions and received more erythropoietin.

RBV-induced anemia is a major problem in the treatment of hepatitis C. In the present study, one patient who developed anemia during treatment had ischemic coronary disease and blood transfusion was necessary in two other patients. Several studies have addressed the dilemma of anemia in the treatment of this population. In fact, renal function declines with age.13 As a consequence, the clearance of RBV may be compromised, increasing the toxic effects of this drug and consequently the risk of anemia.14 Therefore, caution is needed when treating elderly patients despite the availability of recombinant erythropoietin, which has recently contributed to a better management of treatment-induced anemia, promoting an increase in serum hemoglobin levels and treatment compliance and consequently increasing the chance of SVR15-17.

Despite the high rates of adverse effects among older patients seen in the present study, the rate of treatment discontinuation due to adverse events was not significantly higher when compared to the nonelderly group. In a recent study, Nishikawa, et al.,18 also found no significant difference in the frequency of treatment discontinuation due to side effects between elderly and non-elderly patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with Peg-IFN and RBV.

In the present study, no significant differences in the use of erythropoietin, Peg-IFN and RBV dose reductions, frequency of treatment discontinuation due to adverse effects, or treatment duration were observed between elderly patients who achieved SVR and those who did not. Gianninni, et al.,19 also found no association between Peg-IFN or RBV dose reduction and SVR in patients with chronic hepatitis C older than 65 years.

The present results showed that only low pretreatment levels of hemoglobin and elevated glycemia had a negative impact on SVR in elderly patients, suggesting that baseline conditions are fundamental for the tolerance to and success of treatment. In older adults, the prevalence of changes in glucose metabolism is high20 and evidence indicates that low glucose tolerance and diabetes interfere negatively with the hepatitis C treatment response.21–24 Thus, these abnormalities should be corrected before treatment in order to achieve an SVR in this specific group of patients.

ConclusionThe present study showed that older age was a negative predictive factor of SVR in patients with genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C treated with Peg-IFN and RBV. In addition, the SVR rate was lower in the elderly group compared to non-elderly patients. However, the low SVR rate could not be explained by a higher frequency of side effects, RVB dose reduction, or treatment discontinuation. On the other hand, baseline conditions of elderly patients were more important than treatment variables. Among elderly patients, the best candidates for hepatitis C treatment are those with elevated pretreatment hemoglobin levels and adequate glycemic control.