Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a frequent complication of cirrhosis, but the clinical and prognostic significance of the progression of mental status in hospitalised cirrhotics is unknown. We aimed to investigate the prognostic significance of serial evaluation of HE in patients hospitalised for acute decompensation (AD) of cirrhosis.

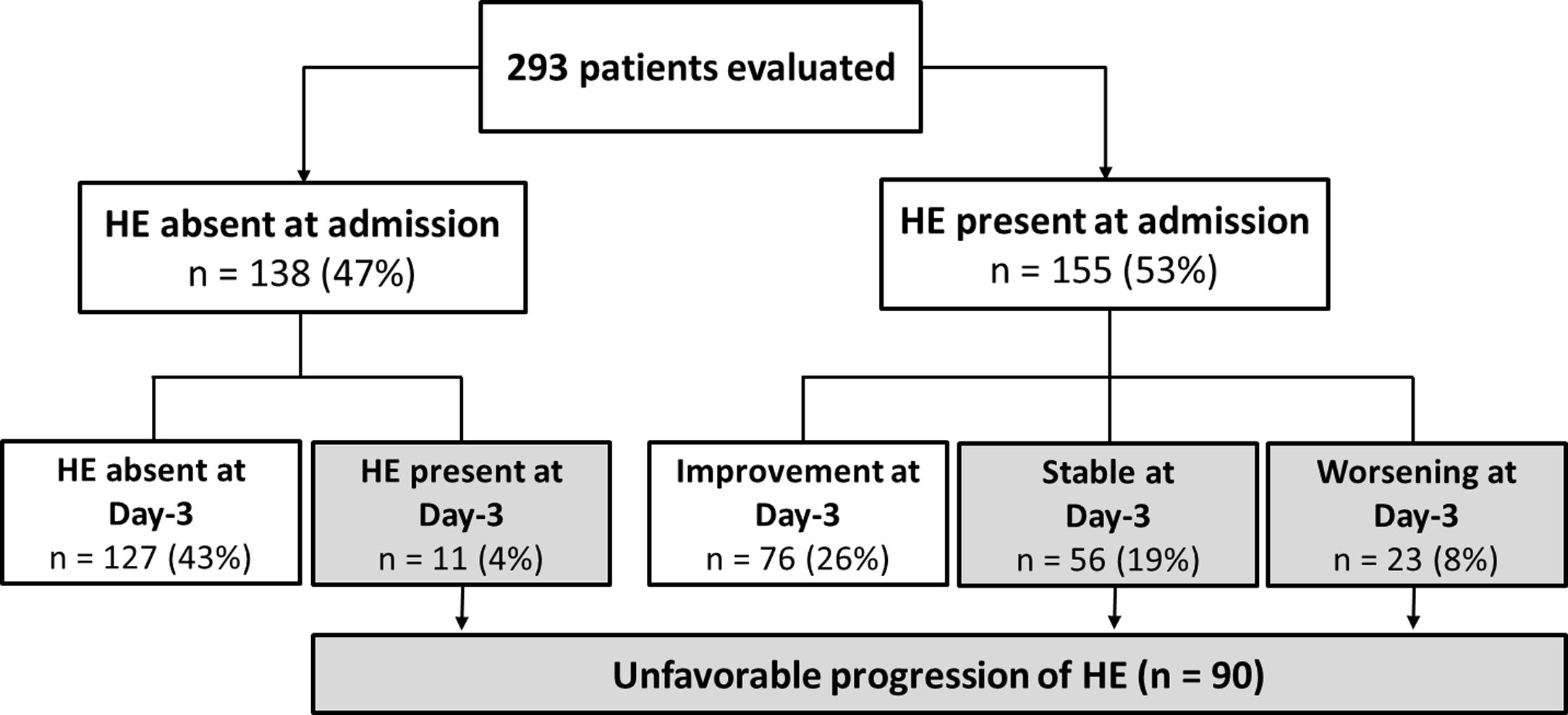

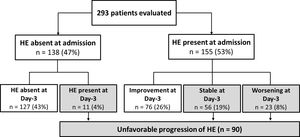

Materials and methodsPatients (n=293) were evaluated for HE (West-Haven criteria) at admission and at day-3 and classified in two groups: (1) Absent or improved HE: HE absent at admission and at day-3, or any improvement at day-3; (2) Unfavourable progression: Development of HE or HE present at admission and stable/worse at day-3.

ResultsUnfavourable progression of HE was observed in 31% of patients and it was independently associated with previous HE, Child–Pugh C and acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF). MELD score and unfavourable progression of HE were independently associated with 90-day mortality. The 90-day Kaplan–Meier survival probability was 91% in patients with MELD<18 and absent or improved HE and only 31% in subjects with both MELD≥18 and unfavourable progression of HE. Unfavourable progression of HE was also related to lower survival in patients with or without ACLF. Worsening of GCS at day-3 was observed in 11% of the sample and was related with significantly high mortality (69% vs. 27%, P<0.001).

ConclusionAmong cirrhotics hospitalised for AD, unfavourable progression of HE was associated with high short-term mortality and therefore can be used for prognostication and to individualise clinical care.

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is defined as a brain dysfunction caused by liver insufficiency and/or portosystemic shunts, and it is one of the most common complications of liver cirrhosis, resulting in significant impairment of the quality of life and frequent hospitalisations [1]. The diagnosis of HE remains essentially clinical. Patients may present with progressive disorientation, inappropriate behaviour, and acute confusional state with agitation or somnolence, stupor, and, eventually, coma [1]. A wide spectrum of motor disorders can be observed in HE, including asterixis, hypertonia, hyperreflexia, and extrapyramidal dysfunction [1]. Episodic HE is usually related to precipitant factors, such as infection, gastrointestinal bleeding, diuretic use, electrolyte disorder, and constipation [2]. Proper management of episodic HE primarily involves the recognition and control of these precipitant conditions, along with general and specific measures such as airway management, intensive care unit admission in severe cases, and non-absorbable disaccharides [3].

It is well known that HE is associated with high mortality, and it is considered one of the major components in the diagnosis of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) [3–5]. Although periodic assessment of HE is advised for patients who are hospitalised for complications of cirrhosis, there are very few data about the clinical and prognostic significance of the progression of mental status in this setting. The absence of improvement or new-onset HE during the first days of hospitalisation might indicate a more severe episode of acute decompensation or failure in controlling precipitant factors that may impact prognosis. Therefore, our aim was to investigate the prognostic significance of the serial assessment of hepatic encephalopathy in patients hospitalised for acute decompensation (AD) of cirrhosis.

2Materials and methods2.1PatientsThis study is part of a project that aims to follow a cohort of adult patients (≥18 years of age) admitted to the emergency room of a Brazilian tertiary hospital due to AD of liver cirrhosis. Details about the methodology were previously published [5] and are briefly presented below.

All consecutive subjects admitted to the emergency room between January 2011 and November 2015 were evaluated for inclusion. Patients in the following situations were excluded: hospitalisation for elective procedures, admissions not related to complications of liver cirrhosis, admission for less than 48h, use of sedatives within the first three days of admission, hepatocellular carcinoma outside Milan criteria, patients who were lost to follow-up, and doubtful diagnosis of liver cirrhosis. In case of more than one hospital admission during the study period, only the most recent hospitalisation was considered. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was established either histologically (when available) or by the combination of clinical, imaging, and laboratory findings in patients with evidence of portal hypertension.

The study protocol complies with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa com Seres Humanos from Federal University of Santa Catarina (reference number 1822/FR402205). Written informed consent was obtained from patients or their legal surrogates before enrolment.

3MethodsAD of cirrhosis was defined as acute development of hepatic encephalopathy, large ascites, gastrointestinal bleeding, bacterial infection, or any combination of these [4]. Acute development of large ascites was defined by the development of grade 2–3 ascites, according to the International Ascites Club Classification [6], within less than 2 weeks. Acute gastrointestinal haemorrhage was defined by the development of an upper and/or lower gastrointestinal bleeding of any aetiology [4].

Active alcoholism was defined as an average overall consumption of 21 or more drinks per week for men and 14 or more drinks per week for women during the 4 weeks before enrolment (one standard drink is equal to 12g absolute alcohol) [7]. Patients were followed during their hospital stay and thirty and 90-day mortality was evaluated by phone call, in case of hospital discharge. Ninety-day mortality rates were estimated as transplant-free mortality.

Child–Pugh classification system [8], Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) [9] and Chronic Liver Failure-Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (CLIF-SOFA) [4] were calculated based on laboratory tests and clinical evaluation performed at admission. ACLF was defined as proposed by the EASL-CLIF Consortium [4].

3.1Assessment of hepatic encephalopathyHE was diagnosed as an impairment of cognition, consciousness, or motor function in patients with cirrhosis with no other apparent causes for mental disturbances. HE was graded according to the classic West-Haven criteria (WHC) [2] and, if it was present, a precipitant event was actively investigated. If not contraindicated, lactulose was initiated orally or via nasogastric tube and the dose adjusted as needed to maintain two to three bowel movements per day [1]. Metronidazole was used as alternative in patients with contraindication or intolerant to lactulose. Patients were clinically evaluated in the first and third days of hospitalisation by one of the researchers involved in the study. To minimise the impact of inter-observer variability, the first and second evaluations for a given patient were performed by the same investigator. All examiners were fourth-year fellows with at least one year experience in clinical hepatology, and trained by the senior investigators specifically for the use of WHC. Patients were divided in two groups according to the WHC: (1) Absent or improved HE – HE absent at admission and at day-3 or any improvement in HE at day-3 (if HE present at admission); (2) Unfavourable progression of HE – Development of HE at day-3 or HE present at admission and stable/worse at day-3. Improvement of HE was defined as any regression in WHC and worsening of HE was defined as any increase≥1 degree in WHC. Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) [10] was also applied at admission and at day-3. Worsening of GCS at day-3 was defined as any decrease in GCS score.

3.2Statistical analysisThe normality of the variable distribution was determined by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Continuous variables were compared using Student's t test in the case of normal distribution or Mann–Whitney test in the remaining cases. Categorical variables were evaluated by chi-square test or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. Multiple logistic regression analysis (forward stepwise regression) was used to investigate the factors independently associated with unfavourable progression of HE and with 90-day mortality. The best cut-off of MELD score for predicting 90-day mortality was chosen based on Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The survival curve was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and survival differences between groups were compared using the log rank test. Correlation between two ordinal variables (WHC and GCS) was evaluated by the Spearman's rank correlation analysis. All tests were performed by the SPSS software, version 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4Results4.1Characteristics of the sampleFour hundred and sixty-seven admissions due to AD of liver cirrhosis were reported between January 2011 and November 2015. Of those, 174 were excluded for the following reasons: admission for less than 48h (n=46), lost to follow-up (n=12) and repeated hospitalisation (n=116). A total of 293 individuals composed the final sample of the study. Table 1 exhibits the characteristics of the included patients. The mean age was 54.78±11.32 years, 72% were males.

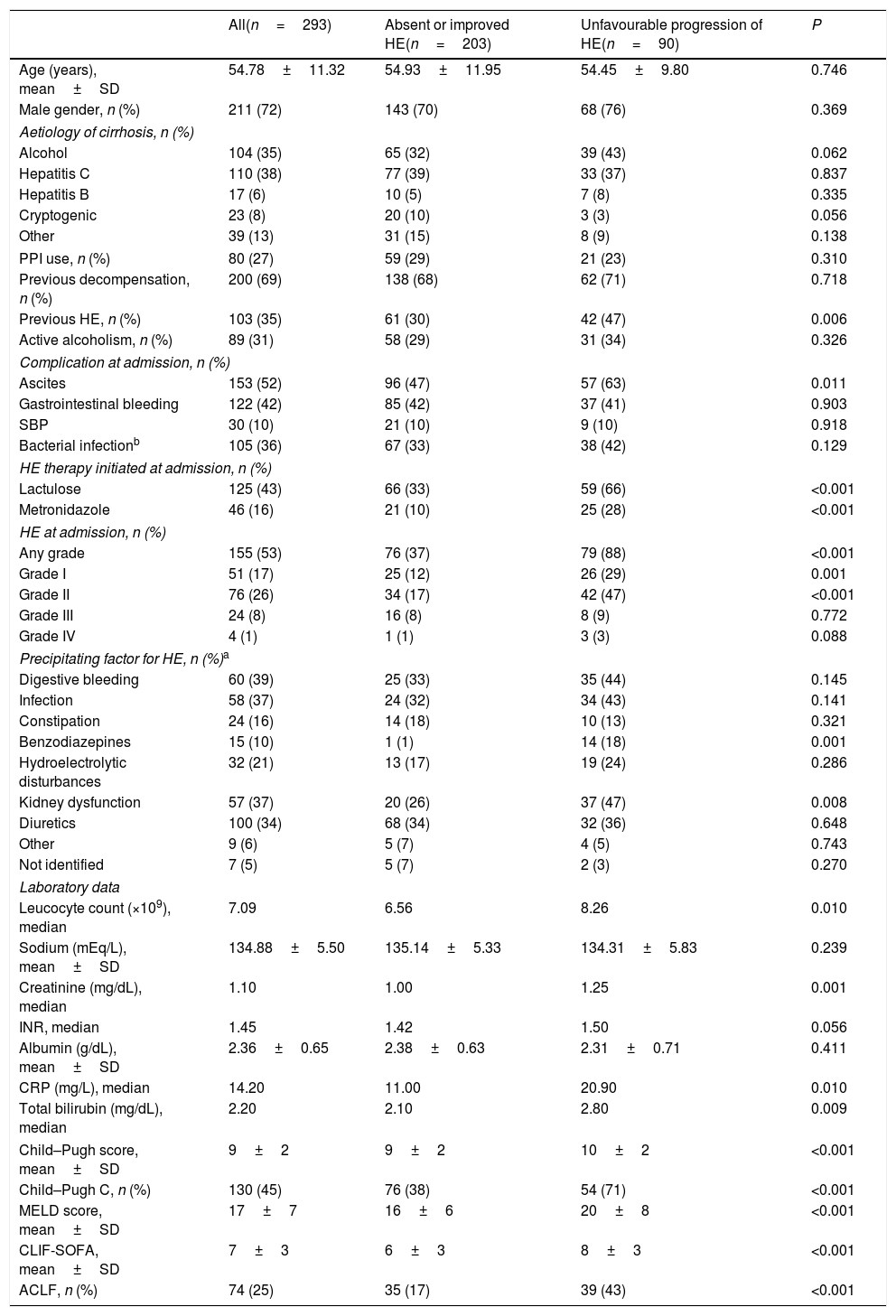

Characteristics of included patients and factors associated with unfavourable progression of HE (early development, persistence or worsening of HE).

| All(n=293) | Absent or improved HE(n=203) | Unfavourable progression of HE(n=90) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean±SD | 54.78±11.32 | 54.93±11.95 | 54.45±9.80 | 0.746 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 211 (72) | 143 (70) | 68 (76) | 0.369 |

| Aetiology of cirrhosis, n (%) | ||||

| Alcohol | 104 (35) | 65 (32) | 39 (43) | 0.062 |

| Hepatitis C | 110 (38) | 77 (39) | 33 (37) | 0.837 |

| Hepatitis B | 17 (6) | 10 (5) | 7 (8) | 0.335 |

| Cryptogenic | 23 (8) | 20 (10) | 3 (3) | 0.056 |

| Other | 39 (13) | 31 (15) | 8 (9) | 0.138 |

| PPI use, n (%) | 80 (27) | 59 (29) | 21 (23) | 0.310 |

| Previous decompensation, n (%) | 200 (69) | 138 (68) | 62 (71) | 0.718 |

| Previous HE, n (%) | 103 (35) | 61 (30) | 42 (47) | 0.006 |

| Active alcoholism, n (%) | 89 (31) | 58 (29) | 31 (34) | 0.326 |

| Complication at admission, n (%) | ||||

| Ascites | 153 (52) | 96 (47) | 57 (63) | 0.011 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 122 (42) | 85 (42) | 37 (41) | 0.903 |

| SBP | 30 (10) | 21 (10) | 9 (10) | 0.918 |

| Bacterial infectionb | 105 (36) | 67 (33) | 38 (42) | 0.129 |

| HE therapy initiated at admission, n (%) | ||||

| Lactulose | 125 (43) | 66 (33) | 59 (66) | <0.001 |

| Metronidazole | 46 (16) | 21 (10) | 25 (28) | <0.001 |

| HE at admission, n (%) | ||||

| Any grade | 155 (53) | 76 (37) | 79 (88) | <0.001 |

| Grade I | 51 (17) | 25 (12) | 26 (29) | 0.001 |

| Grade II | 76 (26) | 34 (17) | 42 (47) | <0.001 |

| Grade III | 24 (8) | 16 (8) | 8 (9) | 0.772 |

| Grade IV | 4 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 0.088 |

| Precipitating factor for HE, n (%)a | ||||

| Digestive bleeding | 60 (39) | 25 (33) | 35 (44) | 0.145 |

| Infection | 58 (37) | 24 (32) | 34 (43) | 0.141 |

| Constipation | 24 (16) | 14 (18) | 10 (13) | 0.321 |

| Benzodiazepines | 15 (10) | 1 (1) | 14 (18) | 0.001 |

| Hydroelectrolytic disturbances | 32 (21) | 13 (17) | 19 (24) | 0.286 |

| Kidney dysfunction | 57 (37) | 20 (26) | 37 (47) | 0.008 |

| Diuretics | 100 (34) | 68 (34) | 32 (36) | 0.648 |

| Other | 9 (6) | 5 (7) | 4 (5) | 0.743 |

| Not identified | 7 (5) | 5 (7) | 2 (3) | 0.270 |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| Leucocyte count (×109), median | 7.09 | 6.56 | 8.26 | 0.010 |

| Sodium (mEq/L), mean±SD | 134.88±5.50 | 135.14±5.33 | 134.31±5.83 | 0.239 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL), median | 1.10 | 1.00 | 1.25 | 0.001 |

| INR, median | 1.45 | 1.42 | 1.50 | 0.056 |

| Albumin (g/dL), mean±SD | 2.36±0.65 | 2.38±0.63 | 2.31±0.71 | 0.411 |

| CRP (mg/L), median | 14.20 | 11.00 | 20.90 | 0.010 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL), median | 2.20 | 2.10 | 2.80 | 0.009 |

| Child–Pugh score, mean±SD | 9±2 | 9±2 | 10±2 | <0.001 |

| Child–Pugh C, n (%) | 130 (45) | 76 (38) | 54 (71) | <0.001 |

| MELD score, mean±SD | 17±7 | 16±6 | 20±8 | <0.001 |

| CLIF-SOFA, mean±SD | 7±3 | 6±3 | 8±3 | <0.001 |

| ACLF, n (%) | 74 (25) | 35 (17) | 39 (43) | <0.001 |

PPI=proton-pump inhibitor; ACFL=acute-on-chronic liver failure; SD=standard deviation; AST=aspartate aminotransferase; ALT=alanine aminotransferase; GGT=gamma-glutamyltransferase; INR=international normalised ratio; CRP=C-reactive protein; MELD=Model for End-stage Liver Disease.

At the first evaluation, 155 patients (53%) presented with HE (grades I, II, III or IV in 17%, 26%, 8%, and 1%, respectively). HE was absent at admission and at day-3 in 43% of the patients, and improved at day-3 among 26% of the subjects. Thirty-one percent of the patients exhibited an unfavourable progression of HE. Among these, in 4% of the cases HE was absent at admission but developed until day-3; in 19% of the cases HE was present at admission and no improvement was observed at day-3; and in 8% of the patients HE worsened at day-3 (Fig. 1).

4.2Factors associated with progression of HE during the first three days of hospitalisationIn the bivariate analysis, unfavourable progression of HE was associated with previous HE, ascites, benzodiazepine use or kidney dysfunction as precipitant factors of HE, higher median leucocyte count, creatinine levels, C-reactive protein (CRP), and total bilirubin. As expected, a higher proportion of patients with unfavourable progression of HE was treated with lactulose or metronidazole at admission. Unfavourable progression of HE was also related to higher mean MELD, CLIF-SOFA, higher proportion of Child–Pugh C, and ACLF (Table 1). A logistic regression analysis to investigate factors independently associated with unfavourable progression of HE was performed including the following variables with P≤0.010 in the bivariate analysis: previous HE, ACLF, Child–Pugh C, MELD, and leucocyte count. Other laboratory variables already present in the models were not included to avoid redundancy. CRP was also not included given the high proportion of missing values (11%). Unfavourable progression of HE was independently associated with previous HE (OR 1.919, 95% CI 1.116–3.299, P=0.018), Child–Pugh C (OR 1.851, 95% CI 1.044–3.157, P=0.035), and ACLF (OR 2.982, 95% CI 1.646–5.404, P<0.001).

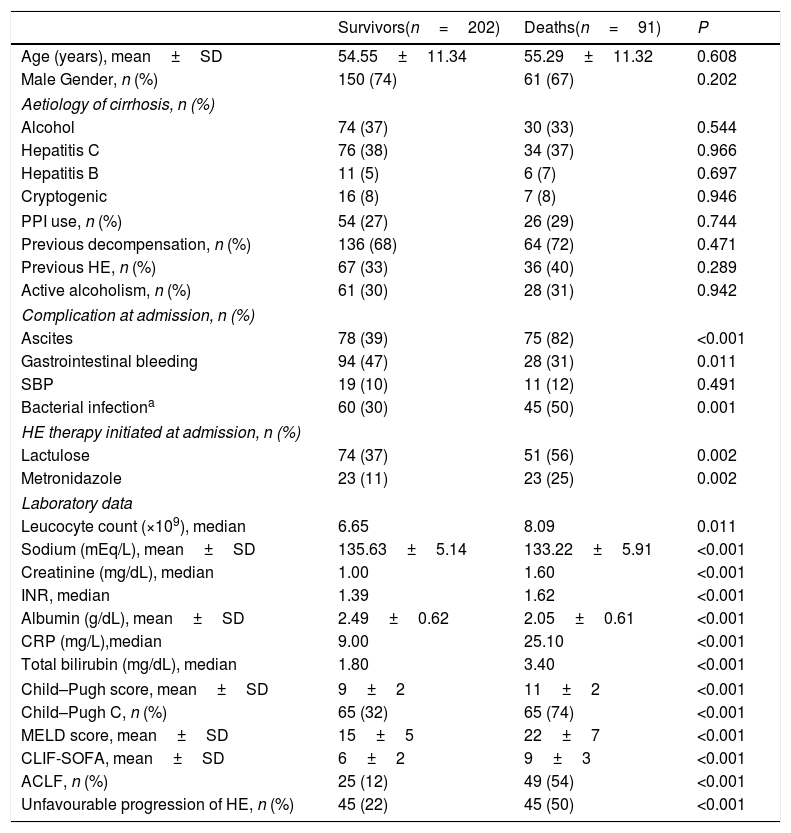

4.3Progression of HE during the first three days of hospitalisation as a prognostic factorOverall, 30-day and 90-day mortality was 26% and 31%, respectively. Bivariate analysis (Table 2) showed that 90-day mortality was directly associated with lactulose or metronidazole therapy, ascites, bacterial infection, Child–Pugh C, ACLF, and unfavourable progression of HE. Ninety-day mortality was also related to higher MELD, CLIF-SOFA, higher median leucocyte count, creatinine, INR, CRP, bilirubin, and lower sodium and albumin.

Factors associated with 90-day mortality among patients with cirrhosis admitted for acute decompensation.

| Survivors(n=202) | Deaths(n=91) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean±SD | 54.55±11.34 | 55.29±11.32 | 0.608 |

| Male Gender, n (%) | 150 (74) | 61 (67) | 0.202 |

| Aetiology of cirrhosis, n (%) | |||

| Alcohol | 74 (37) | 30 (33) | 0.544 |

| Hepatitis C | 76 (38) | 34 (37) | 0.966 |

| Hepatitis B | 11 (5) | 6 (7) | 0.697 |

| Cryptogenic | 16 (8) | 7 (8) | 0.946 |

| PPI use, n (%) | 54 (27) | 26 (29) | 0.744 |

| Previous decompensation, n (%) | 136 (68) | 64 (72) | 0.471 |

| Previous HE, n (%) | 67 (33) | 36 (40) | 0.289 |

| Active alcoholism, n (%) | 61 (30) | 28 (31) | 0.942 |

| Complication at admission, n (%) | |||

| Ascites | 78 (39) | 75 (82) | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 94 (47) | 28 (31) | 0.011 |

| SBP | 19 (10) | 11 (12) | 0.491 |

| Bacterial infectiona | 60 (30) | 45 (50) | 0.001 |

| HE therapy initiated at admission, n (%) | |||

| Lactulose | 74 (37) | 51 (56) | 0.002 |

| Metronidazole | 23 (11) | 23 (25) | 0.002 |

| Laboratory data | |||

| Leucocyte count (×109), median | 6.65 | 8.09 | 0.011 |

| Sodium (mEq/L), mean±SD | 135.63±5.14 | 133.22±5.91 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL), median | 1.00 | 1.60 | <0.001 |

| INR, median | 1.39 | 1.62 | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/dL), mean±SD | 2.49±0.62 | 2.05±0.61 | <0.001 |

| CRP (mg/L),median | 9.00 | 25.10 | <0.001 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL), median | 1.80 | 3.40 | <0.001 |

| Child–Pugh score, mean±SD | 9±2 | 11±2 | <0.001 |

| Child–Pugh C, n (%) | 65 (32) | 65 (74) | <0.001 |

| MELD score, mean±SD | 15±5 | 22±7 | <0.001 |

| CLIF-SOFA, mean±SD | 6±2 | 9±3 | <0.001 |

| ACLF, n (%) | 25 (12) | 49 (54) | <0.001 |

| Unfavourable progression of HE, n (%) | 45 (22) | 45 (50) | <0.001 |

PPI=proton-pump inhibitor; ACFL=Acute-on-chronic liver failure; HE=Hepatic encephalopathy; SD=Standard deviation; INR=international normalised ratio; CRP=C-reactive protein; MELD=Model for End-stage Liver Disease.

Logistic regression analysis was performed including variables with P-value<0.010 in the bivariate analysis (sodium levels, bacterial infection, Child–Pugh C, MELD, ACLF, and unfavourable progression of HE). Therapy for HE and other laboratory variables already present in the models were not included in the regression analysis to avoid redundancy. The parameters that were independently associated with 90-day mortality were MELD score (OR 1.203, 95% CI 1.141–1.269, P<0.001) and unfavourable progression of HE (OR 2.318, 95% CI 1.237–4.342, P=0.009). The 90-day transplant-free survival probability was significantly lower in patients with unfavourable progression of HE (50% vs. 77%, P<0.001).

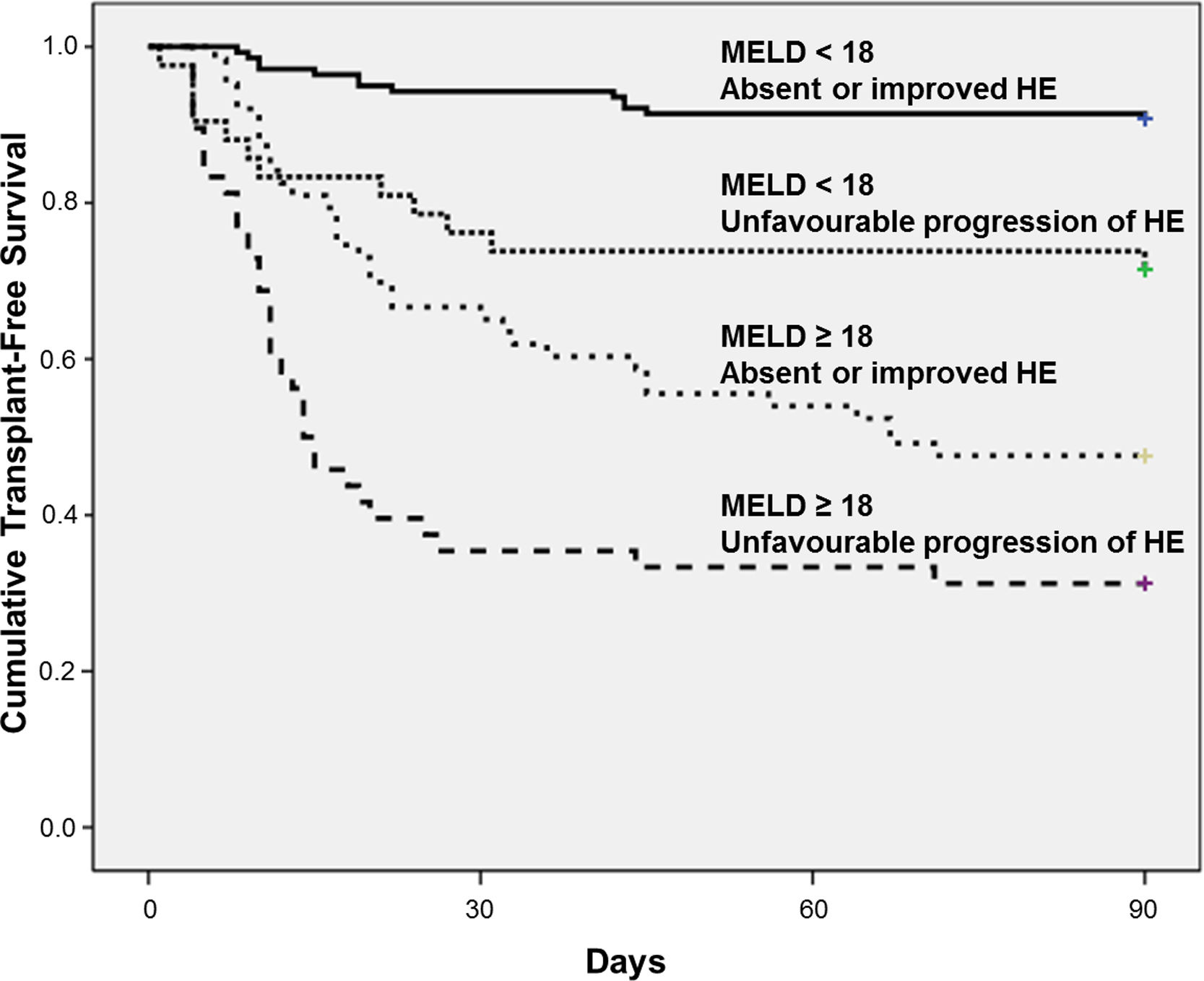

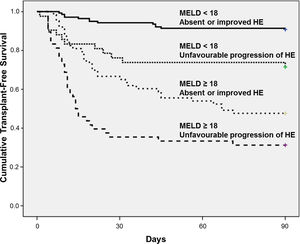

The best cut-off of MELD for predicting 90-day mortality was chosen based on ROC curve. The AUROC of MELD score was 0.809±0.028 and the best cut-off was 18, with 73% sensitivity and 78% specificity. Fig. 2 shows the Kaplan–Meier curves for death according to the progression of HE and MELD categories. The Kaplan–Meier survival probability at 90-day was 91% in patients with MELD<18 and absent or improved HE; 71% in those with MELD<18 but unfavourable progression of HE; 48% in patients with MELD≥18 and absent or improved HE; and only 31% in subjects with both MELD≥18 and unfavourable progression of HE (P<0.001, long-rank test).

4.4Influence of ACLF on HE progression and prognosisAt admission, 119 individuals presented without ACLF or HE. At day-3, HE remained absent in 110 and developed in 9 of those subjects. Among 100 patients without ACLF but with HE at admission, HE improved in 58 subjects, was stable in 20, and worsened in 12 patients. ACLF without HE at admission was observed in 19 individuals. Among those patients, HE remained absent in 17 subjects and developed in 2 patients at day-3. In 55 subjects, both ACLF and HE were present at admission. Among those subjects, HE improved in 18, was stable in 26, and worsened in 11 patients at day-3. Overall, a higher proportion of patients exhibited unfavourable progression of HE among patients with ACLF at admission (53% vs. 23%, P<0.001).

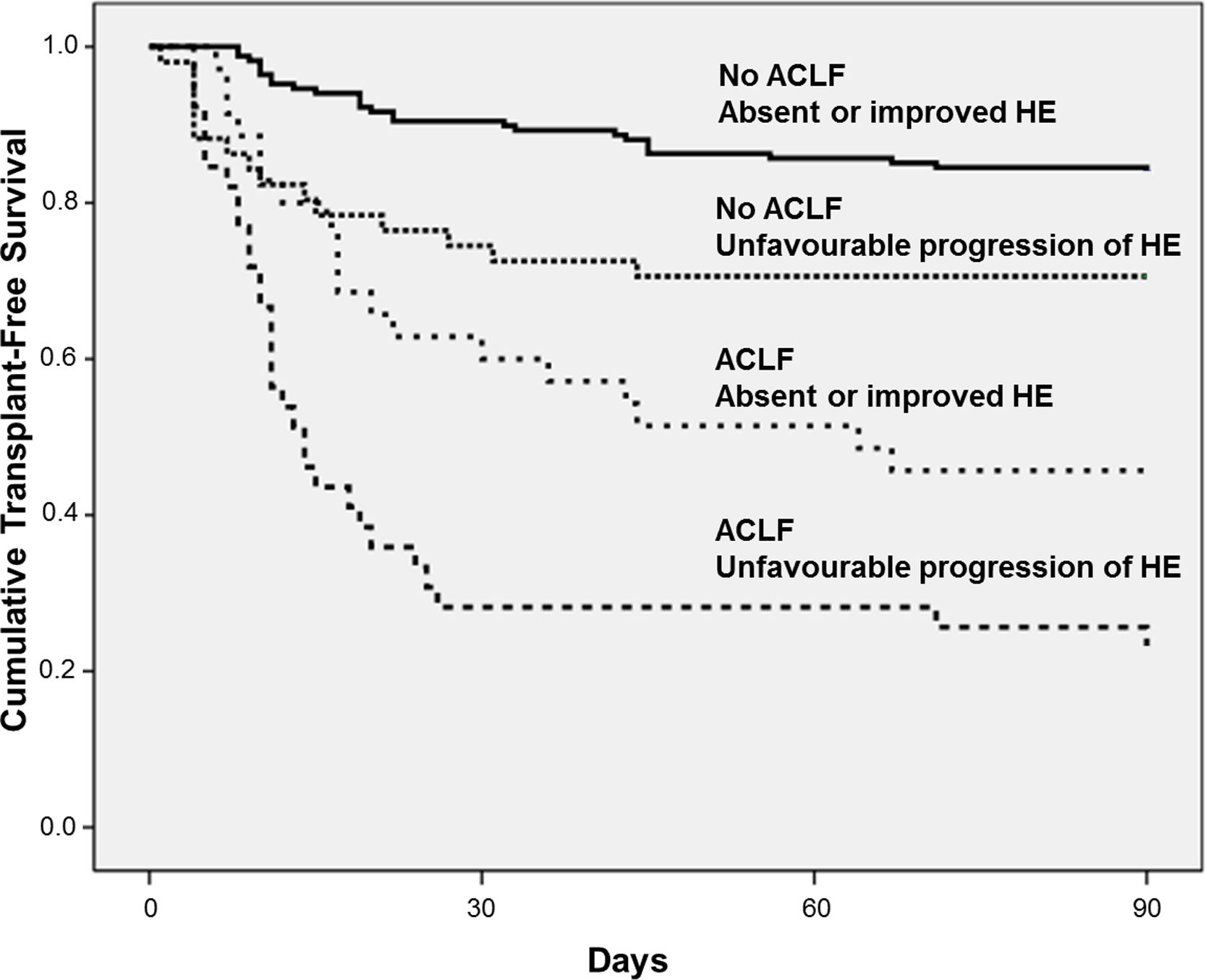

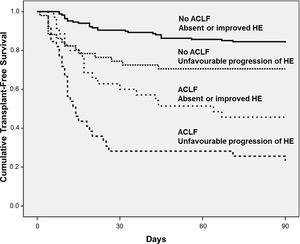

Fig. 3 exhibits the Kaplan–Meier curves for death according to the progression of HE and the presence of ACLF. Patients without ACLF who showed unfavourable progression of HE exhibited lower Kaplan–Meier survival probability as compared to those who remained without HE or improved (71% vs. 84%, P=0.016). Similarly, among those with ACLF, unfavourable progression of HE was associated with significantly lower survival (23% vs. 46%, P=0.012).

4.5Glasgow Coma Scale in the assessment of progression of mental status in cirrhotic patientsAt admission, GCS was 15 in 205 patients (70%), 14 in 48 subjects (16%), and ≤13 in 40 (14%). At day-3, GCS was 15 in 228 patients (78%), 14 in 25 (9%), and ≤ 13 in 39 (13%). GCS was not available at day-3 for one patient. GCS was strongly correlated with WHC at admission (r=−0.736, P<0.001) and at day-3 (r=−0.730, P<0.001). At admission, GCS was 15 in all patients without HE and 3 in those with grade 4 HE according to WHC. Median GCS was 15.0, 14.0, and 12.0 among patients with HE grades 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Mortality rates were 25%, 38% and 53% among patients with GCS of 15, 14, and ≤13 at admission, respectively (P=0.002). Worsening of GCS at third day was observed in only 32 patients (11%) and was associated with higher mean MELD (21.04±6.84 vs. 16.71±6.62, P=0.001) and CLIF-SOFA scores (8.38±2.11 vs. 6.43±2.83, P<0.001), higher proportion of Child–Pugh C patients (65% vs. 43%, P=0.021) and of patients with HE diagnosed by the WHC at admission (81% vs. 50%, P=0.001). Worsening of GCS at third day was related with significantly higher mortality as compared to those who had the GCS stable or improved at second evaluation (69% vs. 27%, P<0.001).

5DiscussionHepatic encephalopathy is one of the most common complications of cirrhosis, and it has been associated with a significant impact on patients’ health-related quality of life [11] and survival, independently of the severity of cirrhosis [3]. HE at admission was observed in 53% of patients included in this study. This number is higher than that reported by the CANONIC (34%) and NACSELD (33%) cohorts [4,12], but similar to that reported by Alexopoulou et al. [13]. These differences are probably explained by the specific characteristics of the cohorts and by the fact that patients were evaluated very early after admission in this study.

In the present study, the majority of patients (69%) exhibited absent or improved HE at day-3. Nevertheless, almost one-third of the subjects developed HE at day-3 or failed to show an improvement. In the bivariate analysis, an unfavourable progression of HE was associated with variables related to the severity of liver disease. However, it was also related to factors that mostly reflect the severity of the episode of AD and inflammatory state, such as a higher leucocyte count, CRP, creatinine levels, and the presence of ACLF. Contrary to previous data indicating that proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) use is associated with an increased risk of HE [14,15], in the present study no association between these drugs and unfavourable progression of HE was observed. In the regression analysis, unfavourable progression of HE was associated with previous HE, Child–Pugh C, and ACLF. Although we were not able to find previous studies that evaluated factors associated with the progression of HE during hospitalisation, these findings are expected, as the severity of HE at baseline impacts these models. A recent sub-analysis of the CANONIC study revealed significant differences between patients with HE that were related or not to ACLF [16]. Based on their results, the authors proposed two distinct presentations of HE in which ACLF-related HE is usually associated with younger age as a consequence of impairment in liver function and bacterial infections, active alcoholism, or dilutional hyponatraemia [16]. Other important features of ACLF-related HE are findings consistent with an exaggerated generalised inflammatory reaction that may play a role in brain dysfunction [16]. The findings observed in the present study probably complement those of the CANONIC study, indicating that ACLF and more intense inflammatory responses at baseline are also associated with a higher risk of development of or failure to improve HE during the first few days of hospitalisation. This also explains the absence of a relationship between PPIs and unfavourable progression of HE in patients recently admitted for complications of cirrhosis, in whom the impact of the severity of liver disease and the precipitant factor is expected to be higher in short-term evolution than that on PPIs use.

The unfavourable progression of HE and the MELD score were independently associated with 90-day mortality among patients hospitalised for AD of cirrhosis. HE is regarded as an important prognostic factor in liver cirrhosis, in either the out- or inpatient setting [16–19]. In the recent analysis derived from the CANONIC cohort, HE was associated with a higher mortality probability that increased significantly as the HE grade increased [16]. In another study that evaluated the long-term impact of HE in patients with cirrhosis, grades 2 or 3 HE were associated with a high mortality in the cohort of hospitalised subjects, even after adjusting for the MELD score [19]. No previous studies evaluating the prognostic impact of changes in the HE grade during hospitalisation were found. Although it is possible that the unfavourable progression of HE in those patients merely reflects the baseline severity of cirrhosis or the precipitant factor, it remains associated with a high 90-day mortality, even after controlling for several important prognostic factors. In addition, a patient who fails to improve or has new-onset HE poses a clinical challenge, and an awareness of the relationship between the event and the prognosis may allow individualisation of care.

Interestingly, PPI use has been related to a poor prognosis among patients without gastrointestinal bleeding that have been hospitalised with HE [20]. Also, in a recent study, PPIs use was shown to be associated with the presence of minimal HE, and related to the development of overt HE and survival in patients with cirrhosis [21]. PPIs are associated with quantitative and qualitative alterations in gut microbiota, small intestine bacterial overgrowth, and bacterial translocation [21–23]. All these effects might explain the undesirable consequences of PPIs in patients with liver cirrhosis. In the present study, PPIs were not related to mortality. However, given the limited sample size, we were not able to evaluate the prognostic impact of PPIs specifically among those with HE.

The prognostic significance of HE progression was evaluated according to the MELD score categories. Patients with absent or improved HE and a low MELD score (< 18) showed a good prognosis (90-day survival≈91%). However, even in subjects with low MELD scores, the unfavourable progression of HE was associated with a poorer prognosis and a 90-day survival of 71%. Similarly, in those with high MELD scores, absent or improved HE at day-3 was associated with a 90-day survival of 48%, versus 31% for those with both high MELD scores and unfavourable progression of HE. These results indicate that the combination of clinical assessment of HE progression over the first three days of hospitalisation and MELD scores provides a well-defined 4-level stratification for short-term prognosis in patients with cirrhosis that are hospitalised for AD. It should be pointed out that the only therapeutic agents available at our institution were lactulose and metronidazole. Lactulose is currently recommended as the first-line treatment of overt HE, and metronidazole is an alternative choice [1]. However, it is possible that some of our patients would benefit from other agents such as rifaximin or intravenous L-ornithine L-aspartate, and the progression of HE might have been influenced by the absence of these therapeutic options.

As mentioned above, ACLF-related HE has specific features, and it has recently been proposed that it should be regarded as an entity that is distinct from isolated HE [16]. For this reason, the impact of HE progression on the prognosis was evaluated in patients with and those without ACLF. Unfavourable progression of HE negatively impacts prognosis regardless of the presence of ACLF. The lowest 90-day survival rate was observed among patients with ACLF who exhibited an unfavourable progression of HE (23%). These findings reinforce the utility of the serial assessment of HE, regardless of the HE type: that is, isolated or ACLF-related.

The GCS was used as an alternative to the WHC to evaluate the progression of cognitive changes during hospitalisation. Although the GCS strongly correlated with the WHC, the vast majority of patients with grade 1 and 2 HE had a GCS score≥14. A reduction in the GCS at day-3 was strongly related to mortality, although it was observed in only 32 patients (11%). The GCS is a useful tool for objective evaluation and continued monitoring of changes in the mental status of non-cirrhotic patients [24]. There are few data regarding the GCS utility in patients with cirrhosis. Original and modified versions of the GCS were used in therapeutic trials of flumazenil for HE [25–27]. A North-American study aimed to describe a modified version of the WHC, named the HE Scoring Algorithm (HESA), showed that the GCS differed among the four stages of the WHC, but the differences between grades 1 and 2 were small and not clinically useful [28]. These data suggest that the GCS might be useful in patients with more severe HE and that the reduction of GCS, although not frequent, is associated with a poor prognosis.

In conclusion, unfavourable progression of HE during the few first days of hospitalisation for AD of cirrhosis was more frequent among patients with a previous history of HE and those who presented with more severe liver impairment and ACLF. The unfavourable progression of HE and the MELD score were independently associated with short-term mortality, and combining both variables appears useful for better stratification of the short-term prognosis. In addition, the serial assessment of HE was also useful in patients with ACLF. These data indicate that unfavourable progression of HE is an important prognostic factor; therefore, it can be used for prognostication and to individualise clinical care.AbbreviationsHE

hepatic encephalopathy

ADacute decompensation

INRinternational normalized ratio

CRPC-reactive protein

SBPspontaneous bacterial peritonitis

MELDModel for End-Stage Liver Disease

CLIF-SOFAChronic Liver Failure-Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

ACLFacute-on-chronic liver failure

WHCWest-Haven criteria

GCSGlasgow Coma Scale

ROCreceiver operating characteristic

PPIproton-pump inhibitor

HESAHE Scoring Algorithm

Author's contributionSchiavon LL and Maggi DC designed the research. Silva TE, Borgonovo A, Bansho ET, Soares Silva P, Colombo BS, Dantas-Correa EB and Narciso-Schiavon JL performed the research. Wildner LM and Bazzo ML contributed with the specific laboratory analysis and sample handling. Schiavon LL and Maggi DC analysed the data. Schiavon LL and Maggi DC wrote the paper.

Informed consentWritten informed consent was obtained from patients or their legal surrogates before enrollment for publication of the case details.

Financial supportFAPESC – Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e Inovação do Estado de Santa Catarina.

Conflict of interestsNothing to report.