Recent efforts to reclassify non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) as metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) are intended to divert attention to the metabolic basis of the disease rather than to alcohol consumption. This reclassification recognizes the role of obesity, sedentary lifestyles and poor dietary habits in the development of the disease, leading to a better understanding of its etiology. Nevertheless, the transition has posed its own challenges, particularly with regard to communication between patient and healthcare professional. Many healthcare professionals report difficulty in explaining the nuanced concepts, especially the term "steatosis". In addition, the change in terminology has not yet removed the stigma, with ongoing debates about the appropriateness of the terms "fatty" and "steatotic". Surveys suggest that while "obesity" may be perceived as more stigmatizing, the medical term "steatotic liver disease" is not considered as stigmatizing, indicating a disconnect in perceptions between healthcare professionals and patients.

Metabolic (dysfunction) associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is a highly prevalent and complex condition, with the potential to result in severe outcomes, including liver failure and liver cancer [1,2]. Beyond its direct impact on liver health, MAFLD also increases the risk of systemic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and chronic kidney disease, underscoring the critical need for comprehensive management and awareness of this disease [3,4].

The term "Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease" (NAFLD), previously used to describe this condition, was difficult to be communicated, contributing to the low awareness of the disease [5]. For example, a statewide survey of 250 primary care physicians (PCPs) in USA revealed widespread recognition of NAFLD as a major health problem, with 83% of PCPs viewing it as such. Despite this, 84% of physicians significantly underestimated the prevalence of NAFLD among the general and obese population, indicating a lack of awareness of the extent of the disease [6]. Furthermore, 91% of PCPs acknowledged the association of NAFLD with metabolic syndrome, yet only 46% actively screened their obese diabetic patients for NAFLD. This disparity between knowledge and action suggests barriers to effective screening and management of NAFLD in primary care settings [6].

In recent years, there has been a shift in the terminology and classification of NAFLD to MAFLD. This redefinition is intended to address the limitations of the previous definition of NAFLD, which focused solely on the absence of alcohol consumption and did not adequately capture the metabolic abnormalities frequently present in affected individuals. The transition from the term NAFLD to MAFLD aims to mitigate these problems by focusing on the central metabolic dysfunction of the disease and distancing it from the stigmatizing implications associated with alcohol consumption and obesity. It is believed that these nomenclature changes will encourage greater awareness of the disease among healthcare professionals and promote a more comprehensive treatment approach that addresses the broader spectrum of metabolic dysfunction [7,8].

By adopting the MAFLD terminology, various metabolic factors that contribute to FLD are recognized. This reclassification is intended to provide a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the disease [9]. Nevertheless, despite these efforts, a recent suggestion suggested a new nomenclature metabolic dysfunction-associated staetotic liver disease (MASLD). Despite the potential risk of confusion from the frequent changes over a short span of time, the key suggested for this change is that the word fatty is stigmatising. We realize there is some confusion around stigma that has resulted in misleading statements. This review aims to systematically review the evidence of the stigma of the word fatty liver, particularly in the context of the transition from NAFLD to MAFLD and MASLD. We cover three angles, patients and health care perspective, evidence from quantitative studies and the global perspective.

2What is stigma?Stigma is defined as an “attribute that is deeply discrediting”, reducing the person who possesses it “from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one”. Stigma fall into three categories or sources, namely those with “visible abominations of the body”, those with “blemishes of individual character”, and those with “tribal stigma” which affects all members of the group and are passed from generation to generation [10]. The struggle to avoid stigma is also incomplete without serious attention to how other parts of the world think. In different cultures, what constitutes stigma can vary significantly, influenced by local values, beliefs and historical contexts [11]. For example, in some societies, mental illness is highly stigmatized and often seen as a sign of weakness or spiritual failure, while in others there may be a higher level of acceptance and understanding [12]. Similarly, certain physical conditions or disabilities may be viewed with empathy and support in one culture, but may lead to social exclusion in another [13]. The influence of social media and the digital environment on stigma is particularly notable. While these platforms have enabled individuals and advocacy groups to share their stories, raise awareness and create supportive communities, they can also serve as a breeding ground for misinformation and negative stereotypes, highlighting the double-edged impact of technology on public health issues [5,14,15].

These variations underscore the importance of a global perspective in addressing stigma, recognizing the diverse ways in which it manifests and is perceived in different societies. But also, striking the right balance between adopting a potential non-stigmatising term and complicate matters by medicalisations the terms.

2.1Patients’ perspectiveIt's important to recognize that individuals with obesity and fatty liver disease (FLD) are a valuable source of knowledge. According to a recent statement by ELPA/EASO, patients with NAFLD often face stigma due to the presence of "alcohol" or "alcoholic" in the name (type 2 stigma). This is particularly relevant in areas with religious and cultural prohibitions on alcohol consumption, and for pediatric patients who may not have relevant alcohol consumption but still face stigma [16,17]. However, it's been argued that the term "fatty" is stigmatizing, which is conceptually and factually flawed. This misunderstanding may stem from a lack of knowledge about what stigma actually is.

It's important to note that while a fat body may be considered physically deviant due to its visibility (type 1 stigma), this is not the case for fatty liver, which is not visible (Fig. 1). Additionally, studies have shown that even for individuals living with obesity, 80% prefer the term "fat", which results in less stigma [18,19]. In some cultures, being fat is even regarded as a sign of good health. Members of the "Fat Acceptance movement" embrace the term as a positive, self-identifying, and political term, similarly to how LGBTQ+ individuals have reappropriated "queer".

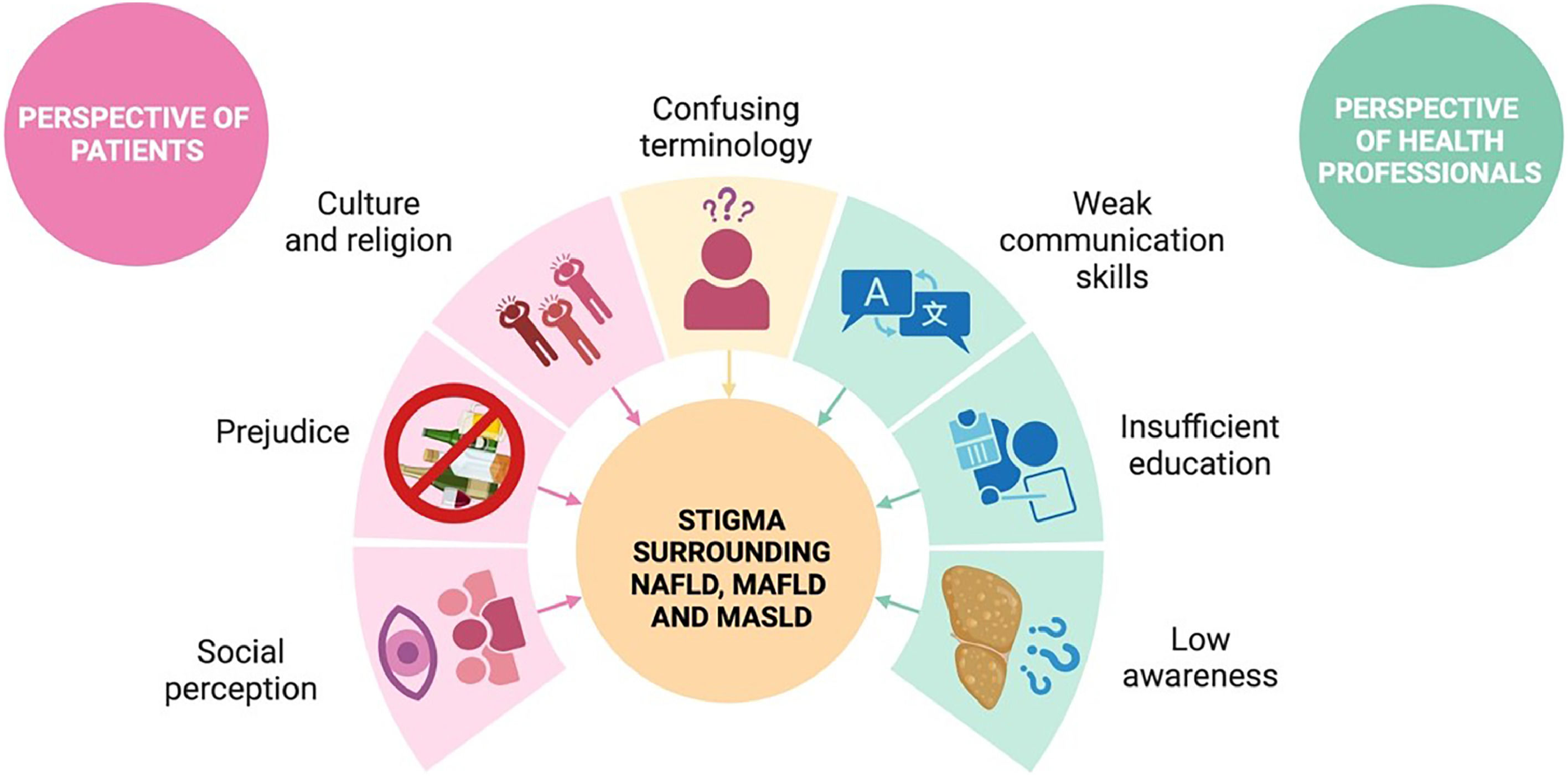

The stigma surrounding NAFLD, MAFLD and MASLD. This figure illustrates the complex stigma associated with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD), Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD), and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) from the perspectives of both patients and healthcare professionals.

The perspective of healthcare professionals on NAFLD, MAFLD and MASLD reflects a complex mix of awareness, knowledge gaps, and changing attitudes toward the diagnosis, treatment, and terminology of FLD [20,21]. Despite the high prevalence and significant health risks associated with these conditions, there remains a notable gap in overall understanding among medical professionals [22,23]. The transition from the use of NAFLD to more inclusive terms such as MAFLD reflects an effort to better characterize the disease beyond its association with alcohol consumption and highlight its metabolic roots. This change is also intended to reduce stigma and more accurately represent the spectrum of individuals affected by the disease, regardless of their body weight or drinking habits [20,21]. Nevertheless, this evolution in terminology and understanding presents its own challenges. Some healthcare professionals are concerned that further change in names and criteria by suggesting MASLD may create confusion among physicians and patients, which could affect disease recognition and treatment [21,24].

3Evidence from quantitative studiesCurrently, FLD and steatotic liver disease (SLD) continue to be closely examined. To assess the impact of these changes in a quantitative manner, surveys have been conducted to evaluate public attitudes and perceptions of this disease. These studies delve into various aspects, such as understanding of the disease, attitudes toward affected individuals and the influence of terminology on efforts to reduce stigmatization [22,25].

A global survey delves into the discordance between healthcare providers and patients regarding the perception of stigma, with terms like "obesity" perceived as stigmatizing but not "fatty". About 48% of patients disclosed their disease, mostly using the term "fatty liver", pointing to a preference for direct language and precluding any signs of stigma as this is the same disclosing rate for other diseases [23].

Consistently, another study from Mexico explores the specific patient perspective on the stigma of the term "fatty" in MAFLD among a Mexican cohort. This study interestingly found that while the term "alcohol" in the disease name was viewed as stigmatizing, the term "fatty" was not suggesting a regional variance in the perception of disease-related stigma [25]. Consistently, surveys and analyses reveal that patients and the public have not found the term "fatty" in MAFLD stigmatizing to the extent that some professionals feared [8].

Together, these studies debunk the claim that fatty liver is stigmatizing and underscore the imperative for a careful choice of words that neither trivialize the condition nor impose unintended stigma, aiming for a balance that fosters clear communication, accurate disease understanding, and sensitivity to patients' experiences across diverse populations. The impact of disease on patients goes beyond their interactions within the healthcare system; it can permeate all aspects of their lives, affecting their mental health, social relationships and quality of life [26]. The perception of stigma associated with MAFLD presents a nuanced landscape.

4Global perspectiveAny new change or proposal should take in consideration a global perspective. A recent study examined the translation of "fatty" and "steatotic" into 17 non-Latin languages spoken by >5 billion individuals globally and revealed that there is no distinction between the two terms, raising further concerns if the confusion that the introduction of MASLD introduced is actually needed or justified. In light of these findings, it is imperative that global health authorities and medical societies collaborate closely in proposing changes in medical terminology. Such collaboration should aim to reach consensus not only on the scientific accuracy of terms, but also on their accessibility and clarity for both healthcare professionals and patients worldwide [27]. Furthermore, the global dissemination of the new terminology requires comprehensive educational campaigns tailored to diverse audiences. These campaigns must take into account linguistic variations and cultural sensitivities, ensuring that all stakeholders have a clear understanding of the terms and their implications [28].

5ConclusionsIn conclusion, it is imperative to distinguish between “benign, justified” and “toxic, unjustified” labelling. The former is merely descriptive but the latter can lead to oppression and the potential for stigmatization is high. For instance, "alcohol" can never be justified as a term to describe fatty liver associated with metabolic dysregulation. In contrast, the use of "fatty liver" is justified and essential for clarity of conversations with patients. Balancing being free of stigma and confusion while preventing trivialization and maintaining motivation is a challenging task. In our opinion, "MAFLD" is a term that meets all the criteria and strikes the right balance. Proposing MASLD creates confusion that is not justified, at least if stigma is a concern.

Author contributionsConceptualization: N.MS, investigation: M.RM, N.MS and X.Q, writing - original draft preparation: M. RM, L.A, N. MS, X.Q, writing - review & editing: M.RM, L.A, N. MS, X. Q, responsible for the integrity: N. MS