Work-related stress and emotional distress among schoolteachers are considered a serious concern in the educational context. Research has shown the beneficial effects of emotional abilities on burnout and psychological problems. Based on the Ability Model of Emotional Intelligence, we designed an emotional-skills training for school teachers intended to promote mental health and well-being.

Materials and methodsThe participants were 340 teachers (74% women), assigned randomly to an experimental and control group. Data on burnout syndrome, emotional symptoms (depression, anxiety, stress), self-esteem and life-satisfaction were collected in three waves: before the training (T1), after the training (T2), and at six-month follow-up (T3). The training program consisted of five two-hour sessions, carried out during three months in groups of 15–20 teachers. Multivariate covariance analyses were carried out, followed by multiple hierarchical regression models.

ResultsResults indicated that teachers who participated in the training program reduced burnout syndrome and emotional symptoms, while incrementing their self-esteem and life-satisfaction in comparison with the control group. These results at T2 were partially maintained at T3.

ConclusionsIn light of these findings, burnout prevention programs based on emotional intelligence should be included in teachers’ professional development plans in order to promote their health and well-being.

El estrés laboral y el malestar emocional en los profesores están considerados una preocupación seria en el contexto educativo. La investigación muestra los beneficios de las habilidades emocionales sobre el burnout y los problemas psicológicos. Basado en el modelo de inteligencia emocional diseñamos un programa de entrenamiento en habilidades emocionales para profesores con el objetivo de promover su salud mental y bienestar.

Materiales y métodosLos participantes fueron 340 profesores (74% mujeres), asignados aleatoriamente al grupo experimental y control. Los datos sobre el síndrome de burnout, síntomas emocionales (depresión, ansiedad, estrés), autoestima y satisfacción con la vida se recopilaron en 3 fases: antes del programa (T1), después del programa (T2) y a los 6 meses de seguimiento (T3). Consistió en 5 sesiones de 2 horas, que se llevaron a cabo durante 3 meses en grupos de 15-20 profesores. Se realizaron análisis de covarianza multivariados y modelos de regresión jerárquica múltiple.

ResultadosLos resultados indicaron que los profesores que participaron en la intervención disminuyeron su nivel de estrés laboral y de síntomas emocionales, aumentando su autoestima y satisfacción con la vida en comparación con el grupo control. Estos resultados en T2 se mantuvieron parcialmente en T3.

ConclusionesA la luz de estos resultados los programas de prevención del burnout basados en la inteligencia emocional deben incluirse en los planes de formación profesional para promover la salud y el bienestar de los profesores.

A growing body of research in school settings has focused on teachers’ physical and psychological problems due to work-related stress (burnout), which is common among educators in European countries (Bauer et al., 2006). In Spain, schoolteachers are one of the occupational groups most vulnerable to suffer from burnout, claiming an impairment of their mental health and emotional stability (Esteras, Chorot, & Sandín, 2014). Prevalence rates of teacher burnout vary considerably among studies, ranging between 8% and 19% when using a more rigid criterion for labeling a person as burned out (León-Rubio, León-Pérez, & Cantero, 2013). Although burnout syndrome is a serious concern among male and female educators from all educational levels, stress levels are higher in teachers with teenage students (Mérida-López & Extremera, 2017).

Causes and consequences of burnout in schoolteachersOne of the main causes of burnout is the teacher–student relationship and its negative outcomes, such as an adverse classroom climate, students’ misbehavior or teachers’ perceived lack of self-efficacy in managing theses disruptions (Hopman et al., 2018). Occupational stressors, such as poor coping resources, heavy workload and the scarce professional recognition are also potential burnout sources, especially when combined (Doménech, 2006). Hence, long-term stressful work conditions may have negative effects on teacher's health and well-being (Luceño-Moreno, Talavera-Velasco, Martín-García, & Martín, 2017).

It is a common belief that burnout causes mental health issues, such as depression or anxiety (Bauer et al., 2006). They can be triggered by stressful stimuli, in situations the individual feels unable to manage or lacks effective coping strategies, therefore experiencing emotional distress (Doménech, 2006). Research indicates that burnout mediates the relationship between work stress and emotional dysfunction (Delhom, Gutierrez, Mayordomo, & Melendez, 2017). Unfortunately, the education system does not cover schoolteachers’ needs as they frequently suffer psychological, social and economic problems (Hernández-Amorós & Urrea-Solano, 2017). For this reason, intervention programs become crucial in order to provide specific training and resources to alleviate burnout (Ahola, Toppinen-Tanner, & Seppänen, 2017).

Relationship with emotional intelligenceIn recent years, studies of personal resources such as emotional intelligence have increased exponentially, evidencing the beneficial effects on burnout and negative mood states (Lavy & Eshet, 2018). Emotional intelligence theory (Mayer, Caruso, & Salovey, 2016) which describes the affective and cognitive mechanisms that process emotional information, considers four interrelated abilities: perceiving, expressing, understanding and managing emotions.

High emotional intelligence provides emotional skills associated with increased well-being, job and life satisfaction, while low emotional intelligence is associated with internalizing symptoms and low self-esteem (Mérida-López & Extremera, 2017). There are different mechanisms that have been hypothesized to underlie the relationship between emotional abilities and well-being (Sánchez-Álvareza, Extremera, & Fernández-Berrocal, 2016). For instance, people who develop emotional awareness and regulation also improve their problem-solving skills, experiencing less stress-related emotions (Mayer et al., 2016). In addition, emotional intelligence promotes mental health by developing coping strategies based on deliberate processing of emotions (Medrano, Muñoz-Navarro, & Cano-Vindel, 2016).

In relation to burnout, emotionally intelligent teachers have a sense of accomplishment and feel enthusiastic toward their work (Lavy & Eshet, 2018). Furthermore, high levels of emotional regulation prevent burnout probably due to the feeling of control over stressful tasks at school and the use of constructive strategies to cope with them (Hopman et al., 2018). Thus, emotional-skills training may be helpful for teachers to cope with stress and to improve their work performance (Mérida-López & Extremera, 2017).

Intervention programs based on emotional intelligenceEmotion-based interventions that have been proposed in school settings in order to prevent burnout and promote well-being among teachers are scarce (Sánchez-Álvareza et al., 2016). More programs should focus on the development and training of emotional skills and abilities (Palomera, Briones, Gómez-Linares, & Vera, 2017). For instance, achieving efficacy in emotional regulation appears to be an effective skill for classroom management and teaching practice (Hernández-Amorós & Urrea-Solano, 2017). Exploring and expressing their feelings accurately is an indicator of less distress (Delhom et al., 2017). Furthermore, gaining emotional competence may foster teacher–student relationships, stress-tolerance and teaching satisfaction (Hopman et al., 2018). For these reasons, educators from all educational levels could benefit from emotional skills training, preparing for their work from preschool to high school or professional grades (Castillo-Gualda, García, Pena, Galán, & Brackett, 2017; Lavy & Eshet, 2018; Palomera et al., 2017; Ulloa, Evans, & Jones, 2016).

Although literature supports the need to integrate emotional literacy in learning and teaching processes (Hernández-Amorós & Urrea-Solano, 2017), previous emotional training programs for teachers are diverse and vary in study design, target group and assessment methods (Hoffmann, Ivcevic, & Brackett, 2018). For instance, Ulloa et al. (2016) designed a training curriculum that consists of three sessions, aimed at enhancing preschool teachers’ emotional competence. Likewise, Dolev and Leshem (2017) followed a two-year emotional development training (12 group and 12 individual sessions) for 21 teachers in a secondary school in Israel. Both studies have methodological limitations, particularly the use of qualitative measures and small samples. In a quasi-experimental study, Palomera et al. (2017) examined the impact of a social and emotional learning program of 40 two-hour sessions, implemented in a pre-service teacher curriculum, using self-report data from 250 undergraduate students in pre-test, post-test assessment, with control groups. Similarly, Castillo-Gualda et al. (2017) conducted a study on a socio-emotional learning program (RULER) that consisted of eight three-hour sessions delivered over a 3-month period to a small sample of teachers from different educational levels. There is a significant gap in the reviewed literature regarding intervention programs designed for teachers. The existing studies present limitations and deficits in providing an adequate sample size and longitudinal data, including a follow-up.

Present studyThe aim of this study was to assess the efficacy of an emotion-based training program to reduce burnout and improve psychological well-being in school teachers at the end of the program and a six month follow-up. We hypothesized that the intervention (1) would decrease the level of emotional symptoms such as depression and anxiety, as well as burnout, and (2) would significantly enhance self-esteem and cognitive aspects of subjective well-being, specifically life satisfaction.

MethodParticipantsThe participants were 340 school teachers, 74.04% women and 25.96% men, from private and public schools in the community of Valencia, Spain. Teachers’ age ranged between 22 and 63 years (M=42.64, SD=9.00). The participating teachers represent all school types of the Spanish education system: 10.61% preschool or Kindergarten (Guardería Infantil), 27.27% elementary school (Educación Primaria), 25.76% secondary compulsory school (Educación Secundaria), 26.36% post-compulsory high school (Bachillerato), 7.27% professional grades (Grado Profesional), 2.73% school counselors (Orientador). Teaching experience among participants varied: 7.19% with 1–2 years of experience, 33.23% with 3–10 years of experience, 34.73% with 11–20 years of experience, 18.56% with 21–30 years of experience, and 6.29% with more than 30 years of experience. All teachers had the Spanish nationality.

ProcedureFor this study, a quasi-experimental design was used with random assignment to an experimental and control group. During the recruitment process, the emotional skills training was offered to teachers as one of several professional training classes organized by the Centre for Teachers’ Permanent Professional Training of Valencia. Teachers, who were interested in the training program, filled in an online application. Inclusion criteria were teachers working at a school with children or adolescents. From the total sample, 135 teachers were randomly assigned to the intervention group. The control group, composed of 205 teachers, received a textbook or digital material about social emotional learning in the classroom as a gift but without face-to-face explanation. Participants were informed about confidentiality and anonymity of the collected data before they gave their consent to participate voluntarily in the study without receiving any economic reward. The t-test of independent samples and chi-square tests, at baseline, indicated that the experimental and control group did not differ significantly (p>.05) on age, gender, school type, students’ education level and years of experience, indicating a correct randomization.

Data were collected from both groups using online surveys in three waves: before the intervention program (T1), after the program was completed (T2) and at six-month follow-up (T3). Of the initial 340 participants who responded to the first evaluation T1, data from 52.65% of the participants was lost in T2 and 43.48% in T3.

All procedures were conducted according to the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013), with permission from the Department of Education, Culture and Sport of the Valencian Community and the Ethics Commission of the authors’ Institution. The results of the study are presented following APA indications for quantitative research in psychology (Appelbaum et al., 2018).

MeasuresBurnout syndrome was measured with the Spanish Burnout Inventory (SBI, Gil-Monte, 2011). The 45-item questionnaire assesses work-related stress and complicated interpersonal relationships in the workplace, including four subscales: enthusiasm toward the job, psychological exhaustion, indolence, and guilt. Participants answered on a 5-point Likert scale (0=never; 4=very frequently, every day). The internal stability in this sample was satisfactory with Cronbach's α ranging between .82 and .88.

Emotional symptoms were measured with the Spanish version of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995; adapted and validated by Bados, Solanas, & Andrés, 2005), assessing the core symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress. Its short form consists of 21 items; scored from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much or most of the time). The internal consistency has been found to be satisfactory in previous studies (Bados et al., 2005), and in our sample α ranging between .89 and .91.

Self-esteem was measured with the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE; Rosenberg, 1965), adapted for Spanish population by Atienza, Moreno, and Balaguer (2000). The instrument consists of 10 items, rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree; 4=strongly agree). The questionnaire is one-dimensional and assesses positive and negative feelings about oneself. The Cronbach's α for the current sample was adequate .82.

Life satisfaction is considered the cognitive dimension of well-being and was assessed using the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985; validated by Atienza, Pons, Balaguer, & García-Merita, 2000). The 5-item scale measures people's overall evaluation of their lives using a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree). The validity and internal consistency in the present study was satisfactory (α=.86).

Intervention programThe intervention program was based on the ability model of emotional intelligence (Mayer et al., 2016) and aimed to reduce work-related stress and enhance psychological well-being by developing emotional abilities and skills. A total of seven groups of 15–20 teachers participated in the seven two-hour training sessions over three months. The first five sessions were devoted to group cohesion and to work on the four abilities of the emotional intelligence model. In the last two sessions the focus was on real world application of emotional abilities in their relationship with assertiveness, conflict resolution, self-esteem and empathy. All seven sessions followed the same methodology strategies, including (1) experiential dynamics such as visualization/meditation and role-playing exercises, (2) individual introspective and group debates, and (3) practice outside the training (see Schoeps, Postigo, & Montoya-Castilla, 2018 for more details).

Data analysis strategyAll the analyses were carried out with SPSS V 24.0. Before testing the hypothesis, descriptive analyses and analyses of variance (MANOVA, ANOVA) were performed to identify possible differences between the experimental and control group at baseline (T1). Furthermore, analyses of covariance (MANCOVA, ANCOVA) were carried out to test the impact of the intervention at T2 and T3, controlling for T1 scores and teachers’ education level (covariables). The effect size (Cohen's d) was calculated to estimate the magnitude of difference between groups.

In addition, multiple hierarchical regression analyses were performed to examine the effectiveness of the intervention program. We calculated the within-person change in all outcome variables from pre- to post-intervention (T2–T1), from pre-intervention to follow-up (T3–T1), and introduced these values as the dependent variables. In the first step, the baseline score and teachers’ education level (covariables) were entered. In the second step, the experimental condition (1=Experimental group, 2=Control group) was introduced as an independent variable. Statistically significant predictions based on the experimental condition, were interpreted as a significant change attributed to the intervention program.

ResultsGroup differences at baselineBaseline scores showed significant differences between the intervention and control group for the variables of burnout (Wilks lambda, λ=.90, F(4)=8.97, p<.001, η2=.10) and emotional symptoms (Wilks lambda, λ=.89, F(3)=12.86, p<.001, η2=.11). More specifically, the univariate contrasts indicate that participants in the experimental group obtained higher scores in excitement toward work, indolence and exhaustion, also in depression, anxiety and stress than the control group. However, no significant difference between groups for the measures of well-being (Wilks lambda, λ=1.00, F(2)=.05, p=.95, η2=.00) were found.

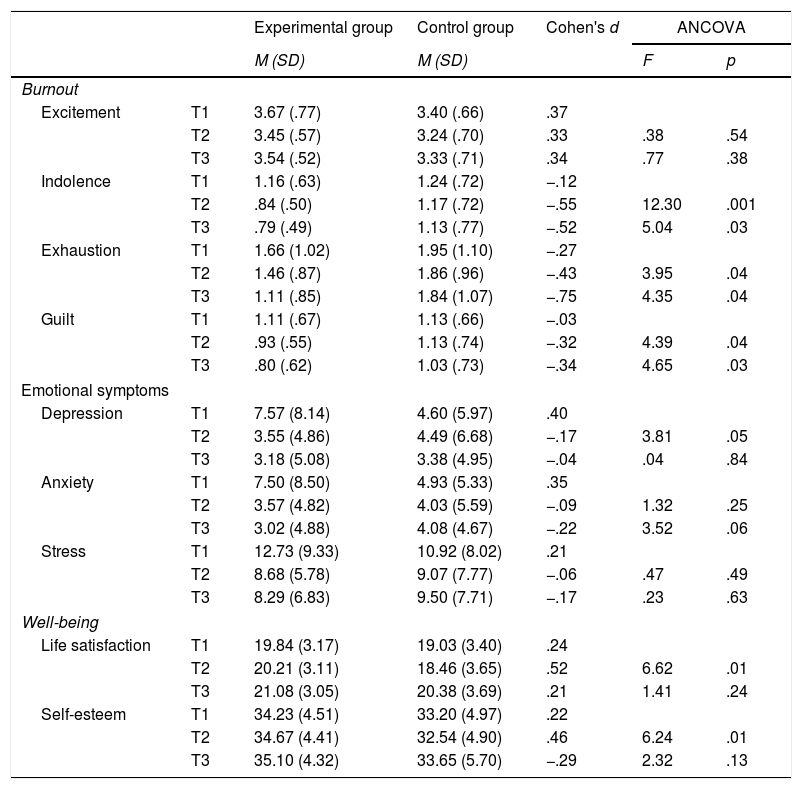

Impact of intervention programResults indicate significant differences for burnout (Wilks lambda, λ=.94, F(4)=2.25, p=.06, η2=.05) and well-being (Wilks lambda, λ=.93, F(2)=5.24, p=.01, η2=.07) at T2, while controlling for baseline scores and teachers’ education level. Nevertheless, no overall differences were found for emotional symptoms at T2 (Wilks lambda, λ=.96, F(3)=2.09, p=.10, η2=.04). In particular, univariate contrasts reveal that the experimental group showed lower indolence, exhaustion, guilt and depression scores than the control group and higher life satisfaction and self-esteem at T2 (Table 1). The effect size was between moderate and high at T2. These differences at T2 were only partially maintained over six month at T3. The multivariate tests were only marginally significant for burnout (Wilks lambda, λ=.91, F(4)=2.24, p=.06, η2=.09), but no significant differences were found for neither emotional symptoms (Wilks lambda, λ=.96, F(3)=1.21, p=.31, η2=.04) nor for well-being (Wilks lambda, λ=.96, F(2)=1.71, p=.19, η2=.04). However, results of univariate contrasts showed significant differences between groups in indolence, exhaustion, guilt, and anxiety in the follow-up, with a moderate to large effect size even when controlling for the effects of different education levels (Table 1).

Post-intervention and follow-up differences between intervention and control groups.

| Experimental group | Control group | Cohen's d | ANCOVA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | F | p | |||

| Burnout | ||||||

| Excitement | T1 | 3.67 (.77) | 3.40 (.66) | .37 | ||

| T2 | 3.45 (.57) | 3.24 (.70) | .33 | .38 | .54 | |

| T3 | 3.54 (.52) | 3.33 (.71) | .34 | .77 | .38 | |

| Indolence | T1 | 1.16 (.63) | 1.24 (.72) | −.12 | ||

| T2 | .84 (.50) | 1.17 (.72) | −.55 | 12.30 | .001 | |

| T3 | .79 (.49) | 1.13 (.77) | −.52 | 5.04 | .03 | |

| Exhaustion | T1 | 1.66 (1.02) | 1.95 (1.10) | −.27 | ||

| T2 | 1.46 (.87) | 1.86 (.96) | −.43 | 3.95 | .04 | |

| T3 | 1.11 (.85) | 1.84 (1.07) | −.75 | 4.35 | .04 | |

| Guilt | T1 | 1.11 (.67) | 1.13 (.66) | −.03 | ||

| T2 | .93 (.55) | 1.13 (.74) | −.32 | 4.39 | .04 | |

| T3 | .80 (.62) | 1.03 (.73) | −.34 | 4.65 | .03 | |

| Emotional symptoms | ||||||

| Depression | T1 | 7.57 (8.14) | 4.60 (5.97) | .40 | ||

| T2 | 3.55 (4.86) | 4.49 (6.68) | −.17 | 3.81 | .05 | |

| T3 | 3.18 (5.08) | 3.38 (4.95) | −.04 | .04 | .84 | |

| Anxiety | T1 | 7.50 (8.50) | 4.93 (5.33) | .35 | ||

| T2 | 3.57 (4.82) | 4.03 (5.59) | −.09 | 1.32 | .25 | |

| T3 | 3.02 (4.88) | 4.08 (4.67) | −.22 | 3.52 | .06 | |

| Stress | T1 | 12.73 (9.33) | 10.92 (8.02) | .21 | ||

| T2 | 8.68 (5.78) | 9.07 (7.77) | −.06 | .47 | .49 | |

| T3 | 8.29 (6.83) | 9.50 (7.71) | −.17 | .23 | .63 | |

| Well-being | ||||||

| Life satisfaction | T1 | 19.84 (3.17) | 19.03 (3.40) | .24 | ||

| T2 | 20.21 (3.11) | 18.46 (3.65) | .52 | 6.62 | .01 | |

| T3 | 21.08 (3.05) | 20.38 (3.69) | .21 | 1.41 | .24 | |

| Self-esteem | T1 | 34.23 (4.51) | 33.20 (4.97) | .22 | ||

| T2 | 34.67 (4.41) | 32.54 (4.90) | .46 | 6.24 | .01 | |

| T3 | 35.10 (4.32) | 33.65 (5.70) | −.29 | 2.32 | .13 | |

Note. M=mean, SD, standard deviation, Cohen's d=effect size, F=F ratio, p=probability, T1=pre-intervention, T2=post-intervention; T3=six-month follow-up; pre-intervention scores and teachers’ educational level were used as covariables.

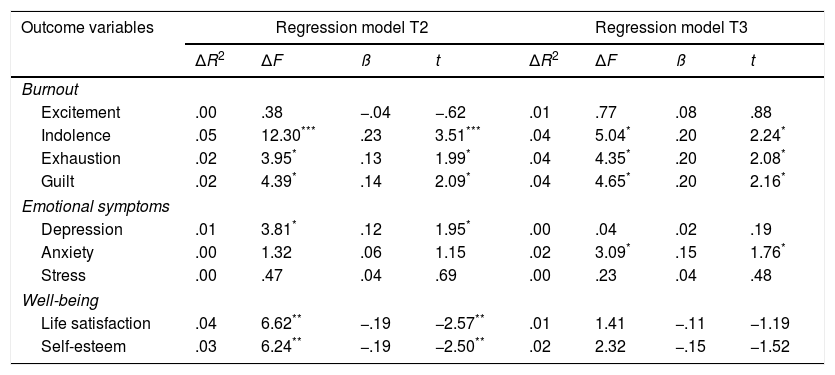

Results revealed that the experimental condition significantly predicted the change in the outcome variables after at T2, controlling for baseline scores and teachers’ education level (Table 2). Specifically, participants in the experimental condition (value 1) increased their level of life satisfaction significantly when compared to those in the control condition (value 2), as indicated by a negative regression coefficient; hence, the lower the condition (1<2), the greater the change. For that reason, participants from the intervention program presented a greater change in life satisfaction. In addition, positive regression coefficients in indolence, exhaustion, guilt and depression indicate that teachers from the intervention group reduced levels of work-related stress and emotional symptoms compared to the control group. Thus, in these outcome variables a negative change is desirable, hence the lower the condition (1<2), the more negative is the change. These results were maintained over six months for indolence, exhaustion, guilt, and anxiety (Table 2).

Predicting changes at post- intervention (T2) and follow-up (T3) in intervention group.

| Outcome variables | Regression model T2 | Regression model T3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔR2 | ΔF | ß | t | ΔR2 | ΔF | ß | t | |

| Burnout | ||||||||

| Excitement | .00 | .38 | −.04 | −.62 | .01 | .77 | .08 | .88 |

| Indolence | .05 | 12.30*** | .23 | 3.51*** | .04 | 5.04* | .20 | 2.24* |

| Exhaustion | .02 | 3.95* | .13 | 1.99* | .04 | 4.35* | .20 | 2.08* |

| Guilt | .02 | 4.39* | .14 | 2.09* | .04 | 4.65* | .20 | 2.16* |

| Emotional symptoms | ||||||||

| Depression | .01 | 3.81* | .12 | 1.95* | .00 | .04 | .02 | .19 |

| Anxiety | .00 | 1.32 | .06 | 1.15 | .02 | 3.09* | .15 | 1.76* |

| Stress | .00 | .47 | .04 | .69 | .00 | .23 | .04 | .48 |

| Well-being | ||||||||

| Life satisfaction | .04 | 6.62** | −.19 | −2.57** | .01 | 1.41 | −.11 | −1.19 |

| Self-esteem | .03 | 6.24** | −.19 | −2.50** | .02 | 2.32 | −.15 | −1.52 |

Note. ΔR2=change in R2; ΔF=change in F; ß=regression coefficient; t=value of t-test statistic.

First step: predictor=pre-intervention score and teachers’ educational level (covariables); Second step: predictor=experimental condition; outcome variables: change scores T2−T1 and T3−T1 were used for the regression analyses. Standardized beta values were reported.

The aim of the present study was to examine the impact of an emotion-based intervention program designed to reduce burnout outcomes and improve well-being in school teachers from different education levels. In relation to the first hypothesis, the program was effective in reducing emotional symptoms and burnout syndrome longitudinally. Teachers who participated in the training program reported less indifference toward the job, psychological exhaustion and feelings of guilt compared to the control group, both after the training ended and six months later. There was no significant change in enthusiasm toward work, indicating that teachers’ motivation and school engagement maintained stable in both groups. Perhaps the teachers in this study were already passionate about their job and that is why they agreed to participate in the first place (Hernández-Amorós & Urrea-Solano, 2017). In addition, the intervention group showed a significant decrease in depression at T2, and a marginal change in anxiety at T3 in comparison to the control group. However, no significant changes in perceived stress in the intervention group were observed. This might be due to the fact that perceived stress (person-related) and burnout (work-related stress), although similar, they are not always bedmates (Bauer et al., 2006). Nevertheless, these results indicate that our emotional intervention program was effective as a short and long-term prevention program for burnout and emotional symptoms in a population as vulnerable as school teachers. The benefit of emotional interventions on teacher's work-related stress and psychological problems has been shown in previous studies, using different theoretical approaches and methodologies (e.g. Castillo-Gualda et al., 2017; Lavy & Eshet, 2018).

Furthermore, the results support the second hypothesis that the intervention program would be effective in enhancing participants’ self-esteem and life satisfaction, although more time and specific training might be needed to maintain those changes over time. Participants in the training group reported feeling more satisfied with their lives and with a higher sense of self-worth than teachers from the control group. Nevertheless, this result was only significant after the training program and was not maintained over six months. The emotional support offered by the group members during the training might have been one of the main reasons for these positive findings (Doménech, 2006). However, once the training ended, the supporting network resolved and the effect disappeared (Mérida-López & Extremera, 2017). Furthermore, the intervention program was designed to last three months; it is possible that by including more sessions through the whole academic year, more stable changes could have been found. Regarding self-esteem, it relates to the sense that the teacher feels self-confident and competent managing his or her classroom (Palomera et al., 2017). The variety of teachers’ education level could explain why the changes in self-esteem were not maintained over time, since effective classroom management is more challenging for teachers working with adolescents, than working with younger children (Hopman et al., 2018). Nevertheless, our results are in line with the literature on emotional intervention programs that can be beneficial to strengthen teachers’ self-esteem and life satisfaction, which in turn enhance their psychological well-being (Ahola et al., 2017; Mérida-López & Extremera, 2017).

Our results support previous research that highlights the strong association between emotional intelligence and teacher burnout (Lavy & Eshet, 2018). Teachers, who were trained in emotional skills, may be less affected from burnout outcomes because they achieve a better perception, understanding and regulation of their own emotional reactions and those of others (Mayer et al., 2016). In addition, emotional intelligence appears to be a protective factor against psychological problems such as depression and anxiety (Delhom et al., 2017). Thus, the development of emotional abilities might reduce the risk of experiencing emotional symptoms by using more adaptive emotion regulation strategies and resolving emotional conflicts more effectively (Sánchez-Álvareza et al., 2016). Our findings also indicate that emotional training in teachers has a positive effect on life-satisfaction and self-esteem, probably due to an advantage in greater social competence, social support and network, which is their main source of emotional balance and well-being (Ahola et al., 2017). For these reasons, emotional training for teachers has an important role in preventing harmful mental health states and promoting their psychological well-being (Mérida-López & Extremera, 2017).

Study limitationsAlthough the results of this study are promising, they must be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, all data used in the study were self-reported, implying a bias of social desirability and increasing the likelihood that relationships would inflate due to the variance of the shared method. Second, online surveys were conducted to reduce costs and time, to increase the number of participants and to facilitate the assessment for the teachers. Nevertheless, the dropout rates were considerable, especially in the control group. This might have been due to the fact that the personal contact during the training program was helpful to reduce experimental mortality. Third, the intervention and control group showed significant differences in initial levels of burnout and emotional symptoms. These differences at baseline must be taken into account when interpreting group differences in later assessments, after the intervention program was completed. Another limitation was that the participants in the study were mostly women, restricting the variability of the sample. However, this limitation reflects the reality of Spanish schools, where female teachers are the majority (Esteras et al., 2014). Finally, this study was conducted with a sample of Spanish school teachers, and the results may differ in other countries with different school systems and cultural contexts. Therefore, it would be advisable for future lines of research to use a cross-cultural design to replicate the results, as well as to apply and validate the intervention program with participants from multiple countries.

Conclusion and practical implicationsDespite these limitations, this study makes an important contribution to the literature on interventions in emotional competence with longitudinal data. Our findings regarding the benefits of an emotion education program hold important implications for teachers and counselors, reducing work-related stress and emotional symptoms, enhancing self-esteem and life satisfaction. Considering that emotional skills and abilities are a predictor of good work performance, coping strategies, and well-being (Sánchez-Álvareza et al., 2016; Ulloa et al., 2016), the emotion education program may be a valuable intervention for educators’ mental health (Luceño-Moreno et al., 2017).

Regarding practical implications, results from the present study demonstrate the need to acknowledge and promote teachers’ emotional abilities during the workday to prevent burnout syndrome. Therefore, it is important to increase support among teachers, by providing knowledge about emotional processes, training their emotional skills and regulation techniques, and facilitating a supportive context where teachers can discuss their emotions. To increase the likelihood of a successful intervention, future studies should tailor the program to participants’ personal and professional needs, taking into account teacher–student relationship and occupational conditions (Dolev & Leshem). In light of these findings, emotional education intervention programs are appropriate for teachers and should be included in school education plans to increase self-efficacy and facilitate work success (Hoffmann et al., 2018).

FundingBoth projects are financed by the Ministery Ministery of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness (PSI2013-43943-R; PSI2017-84005-R) and the University of Valencia (UV-INV-PREDOC15-265738).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors wish to thank all participating teachers for their engagement and collaboration in this study.