In the light of the growing presence of a fourth generation in families, that of the great-grandparents, this study examines the interaction between individuals of this generation and their great-grandchildren taking into account their prior role as grandparents and certain sociodemographic characteristics.

MethodsDescriptive study with 46 participants with great-grandchildren, who completed an interview that involved answering questions about sociodemographic variables and some of the most frequent intergenerational activities. The Wilcoxon, Kruskal–Wallis, and Mann–Whitney U nonparametric tests were used to analyze the data.

ResultsThe data showed that 80.5% of the great-grandparents engage in interaction with their great-grandchildren in all the activities studied; further, these activities coincide with those previously shared with their grandchildren, albeit at a much lower rate. Age, the presence of health problems, and the number of great-grandchildren are related to a reduction in the frequency of certain shared activities between great-grandparents and great-grandchildren.

ConclusionsThe results of this initial study of the great-grandparenthood role can help show how this generation's socializing role can be complementary to the other extended family roles of grandparenthood and parenthood. Our improved understanding of this role can help us better plan for optimizing interventions over the four generations.

ante el aumento continuo de una cuarta generación en las familias, los bisa-abuelos, se estudia su interacción con los bisnietos, teniendo en cuenta su rol precedente de abuelidad y algunas características sociodemográficas.

Métodosestudio descriptivo con 46 participantes con bisnietos, a los que se entrevistó mediante un cuestionario que incluía variables sociodemográficas y algunas de las actividades intergeneracionales más frecuentes. Para analizar los datos se aplicaron las pruebas no paramétricas de Wilcoxon, Kruskal-Wallis y la U de Mann-Whitney.

Resultadoslos datos muestran que el 80,5% de los bisabuelos mantienen una interacción con sus bisnietos en todas las actividades evaluadas; que coinciden, además, con las habidas con sus nietos, pero ahora con una frecuencia significativamente mucho menor. La edad, los problemas de salud y el número de bisnietos aparecen relacionados con la disminución de algunas actividades compartidas entre bisabuelos y bisnietos.

Conclusioneslos resultados de este estudio inicial sobre el rol de bisabuelidad podrían servirnos para mostrar su papel socializador complementario al resto de la red familiar que forman los roles de abuelidad y parentalidad. Su mayor conocimiento nos podría ayudar a mejorar y optimizar intervenciones de 4 generaciones.

The study of human relationships faces new challenges, which include studying aging families and the diverse family forms caused by declining fertility, divorce, remarriage, non-marital childbearing and grandparent-headed households (Silverstein & Giarrusso, 2010), as well as the role of great-grandparents.

Even though women are increasingly choosing to become mothers later in life, Wachter (2003) estimates that by 2030, some 70% of all individuals aged 80 or older will be great-grandparents. Matthews & Sun (2006) found that 32% of families in the United States have four generations or more, with an over-representation of African American families and those with a low socioeconomic level.

Given this increased presence of the fourth generation, and its contact with the first generation of great-grandchildren, it is worth considering whether the type of relationship or role held by these great-grandparents is a continuation of the role they held when they were grandparents or not. The roles and typologies of grandparenthood since Neugarten & Weinstein's pioneer and referential work in 1964 (Formal, Fun Seeker, Subrogate Parent, Reservoir of Family Wisdom, and Distant Figure) in changing family contexts have been well-studied (Bordone, Arpino, & Aassve, 2017; Cherlin & Furstenberg, 1986; Kivnick, 1983; Rico, Serra, & Viguer, 2001; Robertson, 1977; Roberto & Stroes, 1992; Timonen & Arber, 2012; Uhlenberg & Hammill, 1998). However, the role of great-grandparenthood has not; what is more, the few studies that exist often involve considerably fewer participants—we were not able to find any with a sample of more than 52 participants (Barer, 2001; Doka & Mertz, 1988; Drew & Silverstein, 2004; N’zi, Stevens, & Eybert, 2016; Reese & Murray, 1996; Wentowski, 1985), with the exception of one study carried out in Israel with a sample of 103 great-grandparents (Even-Zohar & Garby, 2016).

In studies specifically examining family roles, Drew & Silverstein (2004) studied the impact of the three intergenerational roles (great-grandparenthood, grandparenthood, and parenthood) on the psychological wellbeing of the great-grandparents, and concluded that the more distant the relationships, the lower the significance thereof, and the lower their positive effects on psychological wellbeing. Also, in the same study with the same participants, they found that those who are most satisfied with their role and have the highest self-esteem and least incidence of depression are the following, in this order: parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents.

Doka & Mertz (1988), in their study of 40 great-grandparents, defined two general roles or styles of great-grandparenthood: remote and close. A full 78% of those interviewed felt that their relationship with their great-grandchildren was remote or distant. In this style of relationship, great-grandparents had limited, ritualistic contact with their great-grandchildren; they would see or hear them only during family events and vacations, and they were much more enthusiastic discussing their experiences as grandparents than as great-grandparents. On the other hand, the rest of the sample stated that they had a close relationship with their great-grandchildren: they saw them at least once a month, spoke with them at least once a week, and often cared for them, took them out for visits or shopping trips, and joined them in their leisure or sporting activities (and in many cases, these great-grandparents even kept toys or games in their house for when the great-grandchildren came to visit).

Wentowski (1985) also studied the perception of the great-grandparent's role with 19 great-grandmothers. Here, the focus was on the social, emotional, and behavioral dimensions of this role, on how these dimensions influenced their relationships with their great-grandchildren, and on the significance of these relationships in their daily life. The results showed that geographical distance had the greatest influence, affecting the frequency of visits between great-grandmothers and their great-grandchildren.

Even-Zohar & Garby (2016) studied the role perception of 103 great-grandparents in relation to their quality of life in four dimensions: cognitive, affective, symbolic, and behavioral. The results showed that the continuity and meaning factors (symbolic dimension) were predictors of personal investment (cognitive dimension) and of positive emotions (affective dimension). Also, these factors predicted the help given to great-grandchildren (behavioral dimension). Some sociodemographic variables (good health and economic status, better education and positive emotions) contributed to their total quality of life.

Given the scant literature available on so many aspects of this new family role, it would be interesting to know whether great-grandparenthood is merely a continuation of the previous role of grandparenthood; a simplified, dual version involving the two opposing roles (Doka & Mertz, 1988); or a new role in its own right, which has yet to be defined and described.

For all the above reasons, this exploratory study attempts to analyze the intergenerational activities that great-grandparents share with their great-grandchildren. As a first aim, we want to see their general sociodemographic profile and whether there is any continuity to be found here with the activities that these individuals once shared with their grandchildren, or whether they report any differences in this respect. As a second aim, we would like to study the relationship between certain sociodemographic variables in this group of great-grandparents, such as age, education, health status, and number of great-grandchildren, and the activities that they share with their great-grandchildren.

MethodParticipantsParticipants were a total of 46 men and women with at least one great-grandson or great-granddaughter, with different health and marital status, educational level, and number of children or grandchildren. We excluded those who suffered any cognitive impairment and did not live in their own homes.

InstrumentsWe used a questionnaire with two parts. The first was related to our first aim of determining the participants’ sociodemographic profile, and included: name, sex, age, marital status, education, health problems, and number of great-grandchildren.

The second part was related to our second aim of exploring participants’ interactions both with their great-grandchildren in the present and with their grandchildren in the past, using the same list of 21 items in both cases, and always referring to the (one or two) children met or contacted most frequently. From those 21 items, the first section had a list of 20 of the most-studied activities that frequently involve intergenerational interaction and exclude parents, such as those between grandparents and grandchildren (Castañeda, Sánchez, Sánchez, & Blanc, 2004; Isábal de Marta, 2014; Rico et al., 2001), and those used by Doka & Mertz (1988) in their study with great-grandparents, which covered activities involving formal roles (Offer a snack or light meal…, Host in your home…), informal roles (Go for walks…, Speak on the phone…) and roles of surrogacy/substitution (Babysit on weekends…, Bathe and dress…); further, these activities were classified into three physical contexts for interaction between these two generations: in the great-grandparents’ home (items 1, 2, 8, 13, 16, 18, and 20), such as: Do you provide meals to your great-grandchildren in your own home?; in the parents’ home (items 7, 12, 15, 17, and 19), such as: Do you babysit your great-grandchildren in their parents’ home on weekends?; or in either home or outside the house (items 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 10, 11, and 14), such as: Do your bring your great-grandchildren to any leisure activities and/or Do you pick your great-grandchildren up from school?. The frequency with which the two generations interacted through each of these 20 items was to be rated on a Likert scale as follows: 1 (never), 2 (rarely), 3 (sometimes), 4 (often), 5 (very often). In relation to the reliability or the internal consistency for this questionnaire, we obtained a Cronbach's alpha of 0.88 for the 20 items between the great-grandparents and their great-grandchildren and 0.87 for the same items between them and their grandchildren.

At the end of the second part of the questionnaire, there was a second section with one item, no. 21, which was an open-ended question that allowed for more than one response, asking about other activities shared with great-grandchildren that had not been included on the list of 20 items above. The same open-ended question was also asked at the end of the section on grandchildren.

ProcedureThe questionnaire was distributed via a group of volunteer students in their second year of undergraduate Psychology studies at the ULL to all available participants from amongst the students’ family members, neighbors or acquaintances, all of whom agreed to participate without any obligation.

The conditions of the task and instructions for their application were the same in all cases: it was to be administered heterogenously, in a quiet place, without anyone else present. Participants were to be informed that this was a study exploring great-grandparents’ opinions about their relationships with their great-grandchildren. Given the probable advanced age of the participants, the task be conducted in a personal way, without rushing. Participants were asked to select only one of the five options on the Likert scale to describe frequency of contact for each of the 20 questions in the second part of the task.

Data analysisAfter the data were compiled and codified, the analyses were conducted using the statistical package SPSS v.21. Also, after establishing, by means of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov Normality Test, that our small sample did not follow a normal distribution of data and, moreover, that the variables did not show similar variances, we used three nonparametric statistical tests (Wilcoxon, Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney U). With respect to the analyses carried out, first, in addition to presenting the means of the variables considered to be dependent in this study, the Wilcoxon (of related samples) was used to determine whether there were any significant differences between the frequency of the activities participants shared with their great-grandchildren and those shared previously with their grandchildren. Further, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used, in this case, only for the great-grandparents and their great-grandchildren—to determine whether there were any differences between the frequencies of activities by age, a variable with three ranges in this study: 70–79, 80–84 and 85–96. Also, to determine whether the frequency of activities with great-grandchildren was also influenced by the variables of education, health problems, or number of great-grandchildren, the Mann–Whitney U test was used.

Finally, sex was used as a possible variable rating, given the huge imbalance between men and women in the available sample, which is logical when one considers that women tend to enjoy a longer life expectancy than men (Maklakov & Lummaa, 2013). The same (variable rating) applies to marital status, given the extremely disproportionate differences between levels.

Results- (1)

The sociodemographic profile of this great-grandparents group and the analysis of their perception of the activities they share with their great-grandchildren, and if this pattern of interaction is the same as that shared with their grandchildren, or if different activities are reported for each case.

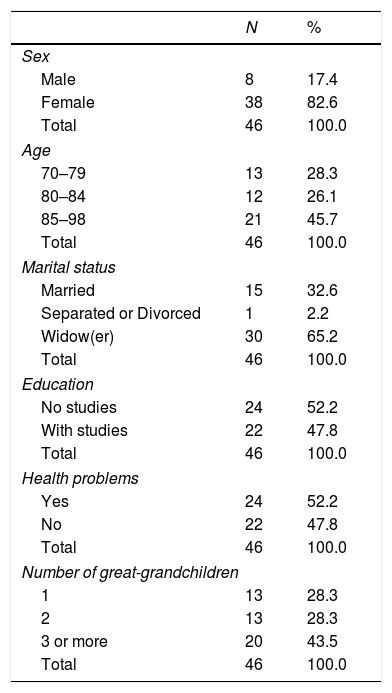

The sociodemographic profile in relation to their sex, age, marital status, education, health problems, and number of great-grandchildren can be found in Table 1. The health problems most frequently indicated were heart conditions (such as arrhythmia), metabolic disorders (such as diabetes and hypertension), and orthopedic conditions (arthritis, osteoarthritis, rheumatism, etc.).

Sociodemographic profile of the sample.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 8 | 17.4 |

| Female | 38 | 82.6 |

| Total | 46 | 100.0 |

| Age | ||

| 70–79 | 13 | 28.3 |

| 80–84 | 12 | 26.1 |

| 85–98 | 21 | 45.7 |

| Total | 46 | 100.0 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 15 | 32.6 |

| Separated or Divorced | 1 | 2.2 |

| Widow(er) | 30 | 65.2 |

| Total | 46 | 100.0 |

| Education | ||

| No studies | 24 | 52.2 |

| With studies | 22 | 47.8 |

| Total | 46 | 100.0 |

| Health problems | ||

| Yes | 24 | 52.2 |

| No | 22 | 47.8 |

| Total | 46 | 100.0 |

| Number of great-grandchildren | ||

| 1 | 13 | 28.3 |

| 2 | 13 | 28.3 |

| 3 or more | 20 | 43.5 |

| Total | 46 | 100.0 |

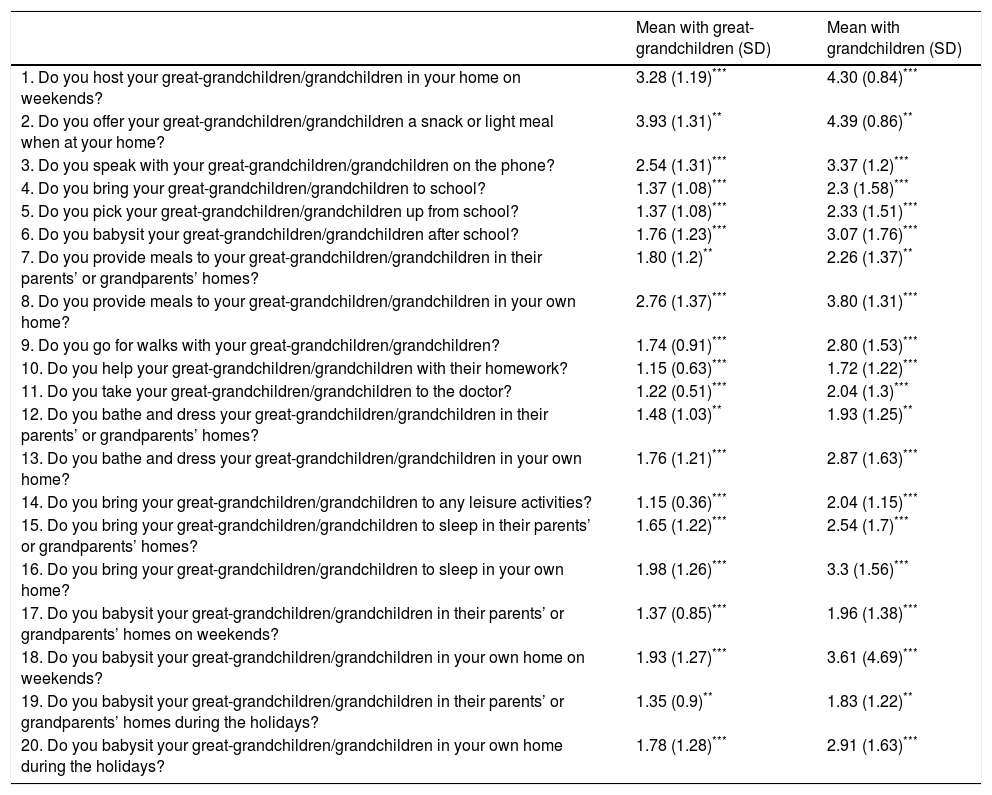

Most great-grandparents (80.5%) reported interactions with their great-grandchildren in all 20 activities included in the questionnaire. They also reported having shared these same activities with their grandchildren. However, the frequency of contact is significantly lower now, in all three types of activities: those in their own home; those in their children's homes, and those in either home or outside the house (see Table 2).

Comparison of frequency of activities with great-grandchildren and grandchildren (1 never, 2 rarely, 3 sometimes, 4 often, 5 very often).

| Mean with great-grandchildren (SD) | Mean with grandchildren (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Do you host your great-grandchildren/grandchildren in your home on weekends? | 3.28 (1.19)*** | 4.30 (0.84)*** |

| 2. Do you offer your great-grandchildren/grandchildren a snack or light meal when at your home? | 3.93 (1.31)** | 4.39 (0.86)** |

| 3. Do you speak with your great-grandchildren/grandchildren on the phone? | 2.54 (1.31)*** | 3.37 (1.2)*** |

| 4. Do you bring your great-grandchildren/grandchildren to school? | 1.37 (1.08)*** | 2.3 (1.58)*** |

| 5. Do you pick your great-grandchildren/grandchildren up from school? | 1.37 (1.08)*** | 2.33 (1.51)*** |

| 6. Do you babysit your great-grandchildren/grandchildren after school? | 1.76 (1.23)*** | 3.07 (1.76)*** |

| 7. Do you provide meals to your great-grandchildren/grandchildren in their parents’ or grandparents’ homes? | 1.80 (1.2)** | 2.26 (1.37)** |

| 8. Do you provide meals to your great-grandchildren/grandchildren in your own home? | 2.76 (1.37)*** | 3.80 (1.31)*** |

| 9. Do you go for walks with your great-grandchildren/grandchildren? | 1.74 (0.91)*** | 2.80 (1.53)*** |

| 10. Do you help your great-grandchildren/grandchildren with their homework? | 1.15 (0.63)*** | 1.72 (1.22)*** |

| 11. Do you take your great-grandchildren/grandchildren to the doctor? | 1.22 (0.51)*** | 2.04 (1.3)*** |

| 12. Do you bathe and dress your great-grandchildren/grandchildren in their parents’ or grandparents’ homes? | 1.48 (1.03)** | 1.93 (1.25)** |

| 13. Do you bathe and dress your great-grandchildren/grandchildren in your own home? | 1.76 (1.21)*** | 2.87 (1.63)*** |

| 14. Do you bring your great-grandchildren/grandchildren to any leisure activities? | 1.15 (0.36)*** | 2.04 (1.15)*** |

| 15. Do you bring your great-grandchildren/grandchildren to sleep in their parents’ or grandparents’ homes? | 1.65 (1.22)*** | 2.54 (1.7)*** |

| 16. Do you bring your great-grandchildren/grandchildren to sleep in your own home? | 1.98 (1.26)*** | 3.3 (1.56)*** |

| 17. Do you babysit your great-grandchildren/grandchildren in their parents’ or grandparents’ homes on weekends? | 1.37 (0.85)*** | 1.96 (1.38)*** |

| 18. Do you babysit your great-grandchildren/grandchildren in your own home on weekends? | 1.93 (1.27)*** | 3.61 (4.69)*** |

| 19. Do you babysit your great-grandchildren/grandchildren in their parents’ or grandparents’ homes during the holidays? | 1.35 (0.9)** | 1.83 (1.22)** |

| 20. Do you babysit your great-grandchildren/grandchildren in your own home during the holidays? | 1.78 (1.28)*** | 2.91 (1.63)*** |

In response to item 21, which inquired after other interactive activities with their great-grandchildren not mentioned in the questionnaire, 19.5% of participants indicated Playing with them; 8.6% named Cooking; and 4.3% indicated Buying clothes, Buying sweets, Singing, Dancing and Going to a soccer game. Although the participants’ sex was not taken into account in the analyses, given the imbalance between women and men, all these latter activities were named by one great-grandmother each, except for the soccer game, which was mentioned by one great-grandfather.

- (2)

Analysis of patterns of interaction with great-grandchildren as a function of the following sociodemographic variables of the great-grandparents: age, education, health problems and number of great-grandchildren.

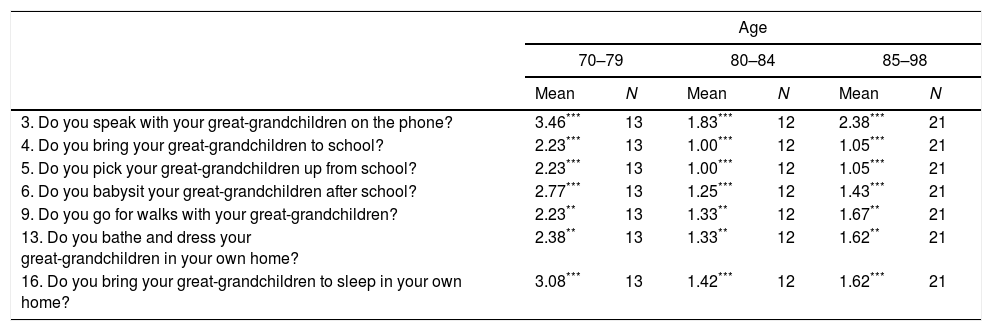

Age. The most significant differences in the activities shared with great-grandchildren were observed in those related to long-distance communication and to bringing the children to school or accompanying them on leisure activities. For all these activities, the greatest frequencies were reported by the great-grandparents in the youngest age range (70–79), with lower frequencies reported by those in the age ranges of 80–84 and 85–98; the only exception to this was Speak on the phone…, which increased from the age of 85 onward (see Table 3).

Frequency of activities with great-grandchildren by different sociodemographic characteristics of the great-grandparents (1 never, 2 rarely, 3 sometimes, 4 often, 5 very often).

| Age | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70–79 | 80–84 | 85–98 | ||||

| Mean | N | Mean | N | Mean | N | |

| 3. Do you speak with your great-grandchildren on the phone? | 3.46*** | 13 | 1.83*** | 12 | 2.38*** | 21 |

| 4. Do you bring your great-grandchildren to school? | 2.23*** | 13 | 1.00*** | 12 | 1.05*** | 21 |

| 5. Do you pick your great-grandchildren up from school? | 2.23*** | 13 | 1.00*** | 12 | 1.05*** | 21 |

| 6. Do you babysit your great-grandchildren after school? | 2.77*** | 13 | 1.25*** | 12 | 1.43*** | 21 |

| 9. Do you go for walks with your great-grandchildren? | 2.23** | 13 | 1.33** | 12 | 1.67** | 21 |

| 13. Do you bathe and dress your great-grandchildren in your own home? | 2.38** | 13 | 1.33** | 12 | 1.62** | 21 |

| 16. Do you bring your great-grandchildren to sleep in your own home? | 3.08*** | 13 | 1.42*** | 12 | 1.62*** | 21 |

| Health problems | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Mean | N | Mean | N | |

| 4. Do you bring your great-grandchildren to school? | 1.00*** | 24 | 1.77*** | 22 |

| 5. Do you pick your great-grandchildren up from school? | 1.00*** | 24 | 1.77*** | 22 |

Education. There were no significant differences observed for any of the activities shared between great-grandparents and their great-grandchildren related to the participants’ level of education. The study sample was divided into two quite homogenous groups, with 52.2% having had no formal schooling and 47.8% having had some formal schooling (39.1% primary, 6.5% secondary, and 2.2% post-secondary).

Health problems. The mean number of health problems reported by participants was as follows, by age group: 1.15 for those aged 70–79; 0.81 for those aged 80–84, and 0.87 for those aged 85–98. It is notable that statistically significant differences related to health status were only found for the activities Bring great-grandchildren to school and Pick great-grandchildren up from school. It was thus observed that great-grandparents with health problems carry out these activities with their great-grandchildren much less frequently (see Table 3).

Number of great-grandchildren. Significant differences were only observed for the item Provide meals to your great-grandchildren in their parents’ or grandparents’ homes. Thus, those participants with few (one) or many (three or more) great-grandchildren provide meals to their great-grandchildren at their own home more frequently than those with two great-grandchildren (see Table 3).

DiscussionGiven the results obtained with this sample of participants and the material evaluated, we can argue that the self-reported interaction between great-grandparents and their great-grandchildren is no different than what they had previously shared with their grandchildren; what is different, of course, is the frequency of these interactions. This tendency coincides with the study of Even-Zohar & Garby (2016). This comparative reduction has been also perceived by a sample of adult great-grandchildren (Roberto & Skoglund, 1996). Grandparents may end up fulfilling these functions, as these relationships are probably closer and more affectionate (González, Ortiz, Fuente, & González, 2008) than relationships shared with the generation of great-grandparents. Of course, it is possible that geographical distance, which was not included in this study, may has influenced the results as well (Even-Zohar & Garby, 2016; Wentowski, 1985).

Sociodemographic variables such as age may also lead to a decrease in the frequency of shared activities, as was indeed found in this study. Thus, great-grandparents in their eighties reported fewer interactions with their great-grandchildren than those in their seventies in seven of the activities surveyed; these covered both the more sedentary activities (such as speaking on the phone or babysitting after school) and the more dynamic ones (bringing them to and picking them up from school, going for a walk). This echoes the findings by Osuna (2006), who observed a decrease in involvement in the care of grandchildren as the grandparent's age increased.

Other variables studied here, such as education, did not end up being significant, possibly due, once again, to the limited sample size, which meant we were forced to divide and compare the participants into two broadly equivalent subgroups—of those with studies and those without—which hid major differences in terms of primary, secondary and post-secondary schooling. This fact may have overlapped with other, significant influences, as has already been seen in three-generation families (Hancock, Mitrou, Povey, Campbell, & Zubrick, 2016).

Another personal variable studied was that of the health status of the great-grandparents, given the greater probability of illness being associated with this age group (Martínez & Fernández, 2008). Only two activities with great-grandchildren ended up being related to the great-grandparents’ health problems. Both were dynamic activities involving moving around and therefore requiring great-grandparents to be functionally autonomous and independent: these were Bringing great-grandchildren to school and Picking great-grandchildren up from school. Although our findings are in line with those of Doka & Mertz (1988), in terms of the direct influence that exists between health status amongst members of the fourth generation and activities they share with the first generation.

The same checking must be done to the relationship between number of great-grandchildren and frequency of contact, not very clear here, to see if it follows the tendency noted by Badenes & López (2011) and Uhlenberg & Hammill (1998) with grandparents, in which the greater number of grandchildren the less contact of the grandparents, so as not discriminate between them.

We can conclude from this initial study that the profile of the family role of great-grandparenthood is perceived by the majority of great-grandparents themselves as being similar to the role of grandparenthood in terms of the type of content or activities shared, but different in terms of the frequency of this pattern of interaction. This central feature—that of reduced contact between the two generations—places this new family role of great-grandparenthood conceptually closer to those grandparenting roles that are styled as formal (Neugarten & Weinstein, 1964; Roberto & Stroes, 1992) or remote (Robertson, 1977), or as the distant figure (Neugarten & Weinstein, 1964; Roa & Vacas, 2001); also, it distances it from the roles where frequency of contact is formally important, such as that of the surrogate parent (Neugarten & Weinstein, 1964) or substitute (Roa & Vacas, 2001; Roberto & Stroes, 1992), or that of the informal or funseeker types (Neugarten & Weinstein, 1964; Roberto & Stroes, 1992).

We must continue to study great-grandparents, albeit with larger sample sizes to allow us to better evaluate, with better controls, these and other factors that influence intergenerational relationships, such as sex, geographical distance, education, socioeconomic level, marital status, etc. (Bosak, 2000; González & De la Fuente, 2008; Hancock et al., 2016; Uhlenberg & Hammill, 1998; Wentowski, 1985). Also, we need to learn more about whether there is continuity in the intergenerational roles, i.e., whether a formal grandparent continues to be formal as a great-grandparent, as has been observed between parents and grandparents (Pinazo & Montoro, 2004), or whether the reverse is true. We should also examine the feeling of transcendence or immortality in this fourth generation (Reese & Murray, 1996) and the expectations held before and after becoming great-grandparents. It would also be worthwhile to compare great-grandparents along maternal and paternal lines, to see if there is continuity in the trend observed between grandparents and grandchildren (Castañeda et al., 2004) that shows greater interaction along the maternal line.

In sum, the role of great-grandparenthood is a new field of psychosocial study, and we must demonstrate its growing presence and importance in new family structures and dynamics, especially in countries with longer life expectancies. The more we know about this new role, the better we can plan appropriate interventions that are in line with each family's needs.