Postprandial hypotension is a known cause of syncope in the elderly. Its prevalence is unknown in our country.

MethodsA prospective cross-sectional study was performed to determine PPH's Prevalence in elderly adults of both an urban and a rural Community in the State of Queretaro. Blood pressure measurements included a basal pre-prandial record, minute 0 recording at the moment they finished the meal and every 10min until a 90min record was complete. We included a medical history, a mental state test for cognitive evaluation (Minimental) and Minnesota Quality of life score and a food macronutrient composition analysis.

ResultsWe included 256 subjects, 78.1±8.8 years old, 195 (76.2%) female. Two-hundred and five subjects (80.1%) had Postprandial hypotension after one or both analyzed meals, with non-significant differences in the studied items. Sixty-six (26.2%) patients had “significant postprandial hypotension”. Patients living in a special care facility had more postprandial hypotension than people at the family home (87–3% vs 69.8% respectively, p<0.0001).

ConclusionsPost-prandial hypotension is a common finding in this elderly population. We did not find distinctive conditions or markers that allow identification of subjects at risk for postprandial hypotension and its complications. This should prompt for routine screenings in specialized facilities to prevent complications.

La hipotensión post-prandial es causa de síncope en el adulto mayor. Su prevalencia se desconoce en nuestro país.

MétodoRealizamos un estudio prospectivo, transversal, buscando la prevalencia de hipotensión postprandial en adultos mayores en residencias de ancianos de la ciudad de Querétaro y en su domicilio familiar en una comunidad rural cercana. Se midió la presión arterial preprandial, al minuto 0 del postprandio y luego cada 10 minutos hasta completar 90. Se hizo historia clínica, evaluación de calidad de vida y prueba de estado mental para valorar estado cognitivo (Minimental), además de analizarse la composición de macronutrientes de los alimentos.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 256 sujetos de 78.1±8.8 años de edad, 195 (76.2%) eran mujeres. En 205 sujetos (80.1%) hubo hipotensión después de alguna de las dos comidas, sin diferencias significativas en la historia, calidad de vida, o composición dietética. Un grupo de 66 pacientes (26.2%) tuvo “hipotensión postprandial significativa”. Eran mayores y tenían más prevalencia de demencia. Los adultos mayores en una residencia tuvieron más hipotensión postprandial que aquellos en el domicilio familiar (87.3% Vs 69.8% respectivamente, p<0.0001).

ConclusionesLa hipotensión postprandial es un hallazgo común en adultos mayores. No se encontraron condiciones o marcadores específicos que permitiesen identificar a los sujetos con mayor riesgo de hipotensión postprandial. Esto puede suponer una necesidad de escrutinio rutinario para prevenir complicaciones.

Syncope is a common finding among elderly people. Three percent of all the visits to an emergency room and between 2% and 6% of all hospital admissions are syncope-related.1 Among these, nearly 80% are patients older than 65 years of age.

There are many causes for syncope in the elderly and it is common that several of them co-exist in the same person. These include arrhythmias, heart disease, medication-related syncope, and autonomic dysfunction such as neurally mediated syncope and orthostatic hypotension as well as postprandial hypotension (PPH).1

Post-prandial hypotension is presumed to be a common issue related to syncope in the elderly but it has been scarcely studied in our country.2,3 Defined as a reduction of 20mmHg in systolic blood pressure after taking a meal,4 its overall prevalence is between 24% and 30% among residents of retirement homes in other countries. Eight percent of the syncope events in that population are possibly caused by PPH.2,4,5

Several factors contribute to the presence of PPH. The aging process could partially explain the abnormal autonomic blood flow regulation to the splanchnic vessels during the digestion process.5 There is a blunted sympathetic response that cannot keep a normal systemic blood pressure when vasodilation occurs in the bowel vessels as a consequence of vasoactive intestinal peptides or even insulin release in response to a higher concentration of simple carbohydrates. Such changes induce vasodilatation, reduce the heart's filling pressure and thus cardiac output, originating PPH and syncope. The gastric emptying rate is another determinant of the plasma glucose levels after a meal that can influence the cardiovascular response to glucose concentrations.6–8

Most patients with PPH are asymptomatic but sometimes unspecific symptoms such as dizziness, weakness, nausea, chest pain or palpitations suggest PPH before serious complications, as syncope and acute heart or cerebral ischemia, appear.9,10

To our knowledge, no study has been made to evaluate HPP's prevalence in our country. Since the elderly population is growing, these issues should be addressed to establish the higher risk profiles or to help defining safety policies. The present study was designed to determine the prevalence of PPH in this population, as well as its relations with other conditions, medications, type of macronutrients and its impact on quality of life and mental status.

MethodsA prospective cross-sectional study to evaluate the prevalence of PPH among elderly subjects in retirement homes (“institutionalized”) and in their family home was conducted. The study included people from two retirement homes in the city of Queretaro and a rural community in the municipality of Ezequiel Montes, Queretaro. In order to identify possible associations with medical history, diet components and changes in mental status and quality of life, several tests were made.

In a first meeting, the patients were told about the study goals and the need to obtain blood pressure records every 10min for 90min after breakfast and lunch. If they accepted, they were given an informed consent form and we obtained their medical history, medications, history of syncope or fainting and chronic illnesses. A minimental test and a Minnesota Quality of life test were included in this main clinical evaluation. Once the history was obtained, we could start with blood pressure measurements every ten minutes the same day at lunch time or the next day during breakfast and lunch time.

We included all the elderly subjects living at their family home or institutionalized that voluntarily wished to participate and were in a stable chronic condition. We eliminated from the analysis the subjects (4) that did not complete the required 90-min measurements for other reasons than symptoms. People with known PPH or any other acute illness, as well as special care needs (enteral nutrition through catheters for example) were not included in the sample.

The protocol was approved by the Research and the Ethics committees of the Universidad del Valle de México, Campus Queretaro (CSUVM 2011-004).

DefinitionsPost-prandial hypotension was defined as a reduction of 20mmHg or more for the systolic blood pressure (BP) reading and 10mmHg or more for the diastolic one, in both cases compared to the baseline measurements (preprandial). We considered that PPH was “significant” when BP dropped below 100mmHg for the systolic value and below 60mmHg for the diastolic one or if the systolic BP drop was superior to 40mmHg or if the diastolic BP fell more than 20mmHg and was symptom-related.

Blood pressure measurementsAll blood pressure recordings were made by one of the investigators and at least one certified nurse with a calibrated device and a standardized measurement technique. The BP measurements were performed after breakfast and lunch that in Mexico are traditionally the most important meals of the day. The basal BP record was obtained after at least a five-minute rest period in a sitting position prior to the meal studied. Immediately after the patient finished his last dish, we recorded the “minute 0” reading and from that moment, every 10min BP was measured for a 90min period.

Quality of life and mental statusDuring the main interview, the patients had to perform a minimental test and a Minnesota quality of life interview, as was done in a previous work.11

Dietary nutrients compositionWhile the patient was having breakfast and lunch, we recorded the sort of meal they were having and its amount in standardized measures such as “one cup” for volumes (coffee, milk, main course of meat or pasta or cooked vegetables) or “one piece” for fruits or bread. A nutritionist analyzed all the registered meals to define the macronutrients composition of each one. We obtained the amount in grams of carbohydrates, lipids and proteins according to the standardized Mexican tables and calculated the percentage of each macronutrient included in every analyzed meal.

Statistical analysisThe continuous variables are expressed as means±standard deviation, and categorical variables are expressed as absolute numbers and proportions. Comparisons between groups were made with T test and X2. We also performed a logistic regression analysis to determine if there were possible associations. The statistical analyses were made with the SPSS 19 software (IBM SPSS 2010, IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York 10504-1722, United States). We performed a first analysis with all the patients that showed PPH diagnostic criteria after any of the meals observed, a second analysis for people that had PPH after both meals, and finally, for patients that showed significant BP reductions after both meals, that is, systolic recordings below 100mmHg and diastolic under 60mmHg or that had a reduction in systolic values beyond 40mmHg and 20mmHg for the diastolic ones. A last comparison was made for people living in their family home against people living in elderly-care institutions.

ResultsDuring a six-month period we recruited 320 elderly people. Sixty of them declined participation, and after the main interview and initial BP recording, 4 of them were excluded because they could not complete the required BP readings period.

We analyzed 256 patients; 195 (76.2%) were female, and the average age for the group was 78.1±8.8 years. Females were older (78.4±9.2 years vs 77.3±7.6 years, p=ns). One hundred and seventeen subjects (45.7%) had hypertension, 21.1% diabetes, and 11.7% had some level of non-incapacitating dementia. Only one patient had a history of syncope, but 41.8% (107) had frequent dizziness episodes and 5.5% (14) had had pre-syncope. Table 1 shows the main findings distributed by gender.

Main characteristics of patients with post-prandial hypotension (PPH) after any meal and patients without it.

| With PPH (n, %) (205, 80.1%) | Without PPH (n, %) (51, 19.9%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 78.1±9 | 78.1±8.3 | 0.99 |

| Female gender (number of patients) | 157 (76.6%) | 38 (76%) | 0.9 |

| Hypertension history (number of patients) | 25 (50%) | 92 (44.9%) | 0.5 |

| Diabetes mellitus (number of patients) | 9 (18%) | 45 (22%) | 0.5 |

| Ischemic heart disease (number of patients) | 0 (0%) | 7 (3.4%) | 0.1 |

| Dementia (number of patients) | 3 (6%) | 7 (13.2%) | 0.1 |

| Syncope history (number of patients) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0.6 |

| Minimental score | 16.2±6 | 15.2±6 | 0.27 |

| Minnesota score | 30.5±15 | 31.5±14.8 | 0.67 |

| Baseline systolic blood pressure after breakfast (mmHg) | 129.9±22.1 | 126.4±15.8 | 0.2 |

| Baseline diastolic blood pressure after breakfast (mmHg) | 76.8±11.2 | 71.1±10.4 | 0.3 |

| Basal vs minimal SBP difference after breakfast (mmHg) | 20.5±12.5 | 11.05±6.9 | <0.0001 |

| Basal vs minimal DBP difference after breakfast (mmHg) | 8.9±7.4 | 2.08±3.3 | <0.0001 |

| Baseline systolic blood pressure after lunch (mmHg) | 124.4±20.4 | 124.1±18.7 | 0.9 |

| Baseline diastolic blood pressure after lunch (mmHg) | 74.8±10.3 | 74.7±10.5 | 0.9 |

| Basal vs minimal SBP difference after lunch (mmHg) | 16.6±11.1 | 11.8±8.5 | 0.002 |

| Basal vs minimal DBP difference after lunch (mmHg) | 8.9±7.4 | 2.08±3.3 | <0.0001 |

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

It was found that 205 (80.1%) subjects had PPH (according to the criteria mentioned above) at some time in the postprandial phase of any of the two meals explored. Table 2 shows the main results. There were neither important differences regarding medical history, age and gender distribution nor regarding symptoms prior to the study.

Main characteristics of patients with post-prandial hypotension (PPH) after breakfast AND lunch and patients without it.

| With PPH (108, 42.2%) | Without PPH (51, 19.9%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 79.5±9.1 | 77±5.6 | 0.04 |

| Female gender (number of patients) | 85 (76.6%) | 38 (76%) | 0.9 |

| Hypertension history (number of patients) | 44 (40.7%) | 92 (44.9%) | 0.7 |

| Diabetes mellitus (number of patients) | 25 (23.4%) | 45 (22%) | 0.7 |

| Ischemic heart disease (number of patients) | 2 (1.9%) | 7 (3.4%) | 0.1 |

| Dementia (number of patients) | 20 (18.7%) | 7 (13.2%) | 0.02 |

| Syncope history (number of patients) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0.6 |

| Minimental score | 15.8±5.8 | 15.2±6 | 0.7 |

| Minnesota score | 30.4±15.4 | 31.5±14.8 | 0.6 |

| Baseline systolic blood pressure after breakfast (mmHg) | 129.3±22.7 | 126.4±15.8 | 0.2 |

| Baseline diastolic blood pressure after breakfast (mmHg) | 77±12.2 | 71.1±10.4 | 0.3 |

| Basal vs minimal SBP difference after breakfast (mmHg) | 17.95±11.3 | 11.05±6.9 | <0.0001 |

| Basal vs minimal DBP difference after breakfast (mmHg) | 15.6±9.0 | 2.08±3.3 | <0.0001 |

| Baseline systolic blood pressure after lunch (mmHg) | 124.6±20.5 | 124.1±18.7 | 0.9 |

| Baseline diastolic blood pressure after lunch (mmHg) | 75.5±10.5 | 74.7±10.5 | 0.9 |

| Basal vs minimal SBP difference after lunch (mmHg) | 20.1±11.5 | 11.8±8.5 | <0.0001 |

| Basal vs minimal DBP difference after lunch (mmHg) | 11.7±6.6 | 2.08±3.3 | <0.0001 |

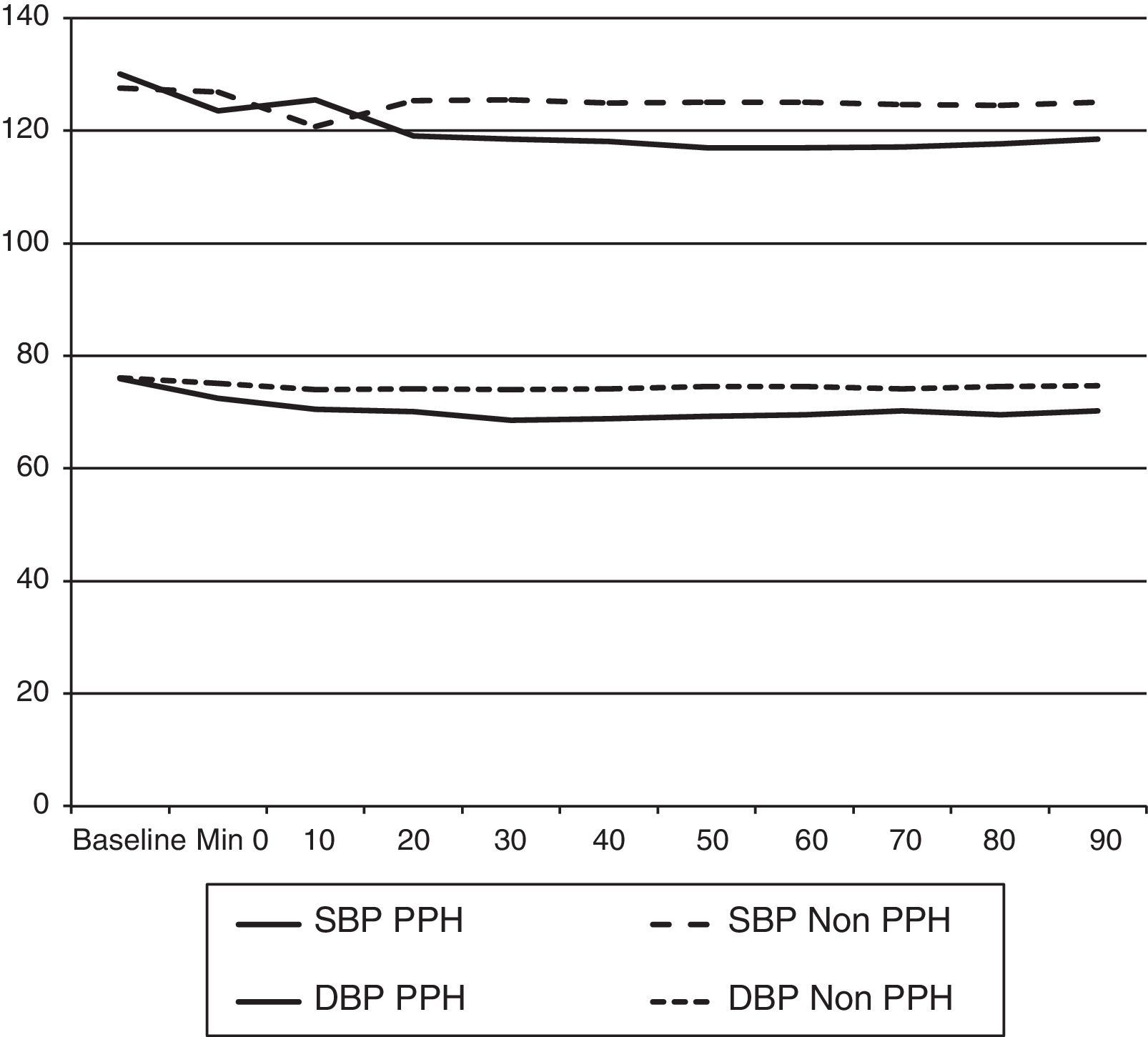

Both systolic and diastolic BP values began to show differences from the minute 20 on for breakfast and from minute 10 on for lunch. Those differences became statistically significant from minute 30 and 20, respectively. The nadir of BP after breakfast was reached between minutes 50 and 60 (Fig. 1). The same was observed after lunch. The BP slowly returned toward baseline levels after minute 70.

The only symptom that showed any difference was drowsiness. There were no significant differences concerning the medications used, even though patients in the PPH group used less Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors (ACEI), diuretics, nitrates and biguanides or sulfonylureas and used more beta-blockers and digoxin.

In this first “gross” comparison, the diet composition did not show any significant differences neither by grams nor by proportion of macronutrients (carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins), but the total caloric intake, although non-significant, was slightly higher in the PPH group.

The Minimental and Minnesota scores’ did not show significant differences between groups.

Post prandial hypotension after breakfast and lunchOne-hundred eight subjects (108, 42.2%) had PPH after both studied meals. These patients were 79.5±9.1 years old (vs 77±5.6 in the non-HPP group, p=0.04), but gender distribution was alike the general description. The PPH group had a higher prevalence of Parkinson's disease (4 vs 0 subjects, p=0.07), dementia (p=0.02), acid-peptic disease (p=0.03) and rheumatic diseases (p=0.03), as well as stroke (4 vs 1 subject, respectively 3.7% vs 2%, p=0.7) (Table 3).

Main characteristics of patients with “significant” post-prandial hypotension and patients without it.

| With SPPH (66, 26.2%) | Without PPH (51, 19.9%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 81.4±9.1 | 77±5.6 | 0.001 |

| Female gender (number of patients) | 58 (87.8%) | 38 (76%) | 0.9 |

| Hypertension history (number of patients) | 22 (33.3%) | 92 (44.9%) | 0.01 |

| Diabetes mellitus (number of patients) | 10 (15%) | 45 (22%) | 0.1 |

| Ischemic heart disease (number of patients) | 4 (6.1%) | 7 (3.4%) | 0.07 |

| Dementia (number of patients) | 13 (19.7%) | 7 (13.2%) | 0.02 |

| Syncope history (number of patients) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0.6 |

| Minimental score | 15±5.7 | 15.2±6 | 0.7 |

| Minnesota score | 33.8±16.6 | 31.5±14.8 | 0.04 |

| Symptoms | |||

| Weakness after breakfast | 11 (16.7%) | 1 (0.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Weakness after lunch | 11 (16.7%) | 2 (1.1%) | <0.0001 |

| Drowsiness after breakfast | 18 (27.3%) | 12 (23.5%) | 0.01 |

| Drowsiness after lunch | 19 (28.8%) | 12 (23.5%) | 0.01 |

| Dietary composition (macronutrients) | |||

| Total calories intake at breakfast (Kcal) | 509.6±362 | 498±231 | 0.7 |

| Total breakfast carbohydrates (g, % caloric intake) | 73.7±50.7 (59.8±14%) | 68.4±31.8 (57.8±15.1%) | 0.3 (0.3) |

| Total breakfast proteins (g, % caloric intake) | 17.3±10 (13.6±4.5%) | 18.1±9.6 (14.5±6.8%) | 0.5 (0.3) |

| Total breakfast lipids (g, % caloric intake) | 17.03±16.7 (25.8±12%) | 16.9±11.4 (28.06±12.8%) | 0.9 (0.2) |

| Total calories intake at lunch (Kcal) | 478±139.7 | 473±160.5 | 0.8 |

| Total lunch carbohydrates (g, % caloric intake) | 65.1±28.4 (53.5±16.08%) | 67.2±30.3 (55.6±15.4%) | 0.6 (0.3) |

| Total lunch proteins (g, % caloric intake) | 25.1±8.5 (21.4±6.1%) | 24.5±10.3 (20.5±6.7%) | 0.6 (0.3) |

| Total lunch lipids (g, % caloric intake) | 12.6±7.1 (23.4±12.7%) | 11.1±5.8 (21.4±11.1%) | 0.09 (0.2) |

The meals’ nutrient composition was alike in both groups. The PPH group had a slightly higher carbohydrate ingestion and calorie intake at breakfast, but there were no significant differences (p=0.6 and 0.9, respectively).

Weakness and sleepiness were the most common symptoms after both meals, and were significantly more frequent in the PHH group (p=0.002 for weakness and p=0.02 for sleepiness). The medications that were more frequently used in the PPH group were benzodiazepines, dopaminergic agents and diphenylhidantoine (p=0.003, p=0.06, and p=0.0001, respectively). The Minimental and Minnesota scores did not show significant differences.

“Significant” post-prandial hypotensionThis group included 66 patients (26.2%) that were elder (81.4±9.1 years vs 77±5.6, p<0.001) and there were more females (87.87%). The main physiologic changes concerned blood pressure readings (Table 4).

Comparison between the Institutionalized patients group and the group of patients living at the family home.

| Institutionalized, 150 patients | Family home, 106 patients | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) | 79.2±9.2 | 76.5±8.1 | 0.01 |

| Female gender (n, %) | 119 (79.3%) | 76 (71.1%) | 0.1 |

| HPP after breakfast OR lunch (n, %) | 131 (87.3%) | 74 (69.8%) | <0.0001 |

| HPP after breakfast AND lunch (n, %) | 81 (54%) | 27 (25.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Significant HPP (n, %) | 39 (26%) | 27 (25.5%) | 0.9 |

| Hypertension | 73 (48.7%) | 44 (41.5%) | 0.2 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 29 (19.3%) | 25 (23.6%) | 0.4 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 6 (4%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0.1 |

| Previous stroke | 7 (4.7%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0.09 |

| Dementia | 25 (16.7%) | 5 (4.7%) | 0.003 |

| Minimental score | 16.5±6.1 | 15.1±5.8 | 0.06 |

| Minnesota score | 30.5±14.1 | 30.8±16.1 | 0.8 |

| Syncope | 1 (0.66%) | 0 | 0.2 |

| Lipothymias – presyncope | 13 (8.7) | 1 (0.9%) | 0.007 |

| Drowsiness | 103 (68.7%) | 39 (36.8%) | <0.0001 |

| Total calories intake at breakfast (Kcal) | 564±266.5 | 414.8±248 | <0.0001 |

| Total breakfast carbohydrates (g, % caloric intake) | 77.7±38.2 (57.7±15%) | 59.01±33.2 (59.3±14.4) | <0.0001 (0.3) |

| Total breakfast proteins (g, % caloric intake) | 20.5±9.8 (14.5±5.6%) | 14.1±8.07 (13.8±7.1%) | <0.0001 (0.3) |

| Total breakfast lipids (g, % caloric intake) | 19.2±13.5 (27.7±12.7%) | 13.9±11.4 (27.2±12.4%) | 0.001 (0.7) |

| Total calories intake at lunch (Kcal) | 468.8±158 | 478.6±157.9 | 0.9 |

| Total lunch carbohydrates (g, % caloric intake) | 67.9±29.5 (57.3±15.5%) | 64.6±29.9 (52.6±15.6) | 0.3 (0.01) |

| Total lunch proteins (g, % caloric intake) | 23.5±10 (19.7±6.7%) | 26.2±9.1 (22.05±10.4) | 0.01 (0.007) |

| Total lunch lipids (g, % caloric intake) | 10.9±6.3 (21.1±12.5%) | 12.08±6.2 (22.5±10.4) | 0.1 (0.3) |

Patients with significant PPH had a higher prevalence of dementia and Parkinson's disease. Most of the symptoms referred in the previous groups were concentrated in the “significant PPH” group, especially weakness and drowsiness after both breakfast and lunch.

Patients with significant PPH showed worst quality of life measurements, but there were no significant differences regarding the medications used, neither in the food macronutrients composition.

Patients living at home compared to institutionalized patientsWe found 150 patients in a specific care facility and 106 patients living in their family home. Institutionalized patients were older (79.2±9.2 years vs 76.5±8.1, p=0.01), and in both groups there were more female subjects. The institutionalized people group showed more chronic diseases, being dementia the most significant (25 patients – 16.7% vs 5 persons – 4.7%, p=0.003).

Post-prandial hypotension was more frequent in the Institutionalized patients group in any of its variants (one of two meals, or both surveyed meals). Even though, when comparing the prevalence of people with significant PPH, the difference between both groups was lost.

Institutionalized patients had a higher total caloric intake in breakfast related to a higher carbohydrate and protein intake. During lunch, institutionalized patients had a higher carbohydrate intake and a lower protein intake than people at the family home.

Patients at family home use ACEI more frequently than institutionalized patients, which in turn, use more calcium channel blockers, aspirin, digoxin, benzodiazepines and vitamin supplements. The logistic regression analysis did not show any strong associations.

DiscussionThe net prevalence of PPH in the elderly has not been extensively studied. According to other authors, it ranges from 25% to 40%.12–14 In the present study we found a very high prevalence of PPH (80%) in an elderly population. This population is similar to the one studied by Aronow in the mid-nineties of the past century, with comparable results concerning PPH's prevalence.15 The differences regarding other author's figures can be related to different PPH definitions, different populations (younger) and different methodologies for BP measurement.16–18 Nonetheless, a Spanish group found similar results regarding the demographic characteristics, as well as in the prevalence of PPH when comparing institutionalized patients to people living in their family home.5

The first two analyses (people with PPH after one or after the two studied meals) did not show significant differences between groups with and without PPH, but the group with “significant PPH” did show some differences regarding the demographic characteristics and the medical history. Those patients were older, had more dementia and a worst quality of life, although these two last issues can be related to the post-prandial hypotension itself.

All the subjects with PPH had more symptoms after meals; specifically they showed more drowsiness and a general feeling of weakness after breakfast and lunch. This can be related to a higher fall and injuries risk in this group of patients. The explanation most surely lies in the differential blood flow induced by digestion reducing cerebral perfusion. But with the food composition analysis, it is very difficult to relate PPH with a high carbohydrate intake. We have to note that the diet composition is very close to the usual suggestions of macronutrients distribution in the institutionalized setting that usually have a nutritionist's participation, but also at the family homes that rely mainly on intuition to prepare food for the whole family. It has to be noted that the institutionalized patients live in an urban setting, and that the people studied in their family home lived mostly in a rural context.

There are small differences regarding the BP behavior when comparing breakfast with lunch. The patients with PPH showed a deeper BP reduction after breakfast than after lunch (the differences were non-significant). When considering vasoactive intestinal peptide, calcitonin and glucose, we cannot have a complete physiopathologic explanation for the differences between meals. An aggregate could be that in the morning, the levels of catecholamines are usually higher, and thus they can prompt disautonomic reflexes such as those seen in neurally mediated syncope.19–25

The main difference regarding chronic illnesses was found in the “significant PPH” group. These patients showed more dementia and Parkinson's disease. In a previous study about orthostatic hypotension,11 we found that Parkinson's disease was related to hypertension and diabetes, and other authors have found similar results with diseases that can compromise the brain nuclei that regulate autonomic function.25–27

Patients with dementia should be given a special consideration. The different prevalence at family home and institution can be explained by several factors, but the more plausible is that it is more suitable for them to receive care in a specialized facility instead of remaining in the family home, since they are sicker patients.

Concerning chronic illnesses such as hypertension, we could not detect any associations as has been described by others.27–29 Perhaps our population is different, or they use different anti-hypertensive medications. Another issue could be the time of administration of the drugs, but our study was not designed to define such a timetable. If the main dose of anti-hypertensive medication was administered in the morning (as it has been done for many years), its effect could be added to the hemodynamic changes during food digestion and an unbalanced sympathetic activity increased in the morning hours.

Heart rate did not show significant changes during the monitored period in this study. This can be related to a defect in the measurement technique or to the mean age of the population studied. Even with a healthy aging, there is a reduction in para-sympathetic activity, highlighted by reduced heart rate variability in the low frequency range in patients even with significant BP reductions. This suggests a blunted baroreflex activity.4

Several studies have tried to relate the blood pressure drop as well as its intensity with the macronutrient composition of the ingested food. Apparently a high carbohydrate intake, especially high glucose contents, is associated with more hypotension.7 Lipids and proteins can induce small transient reductions in BP, but glucose will induce an early increase of BP followed by a significant reduction.30–32

In this study, HPP was common, but since the diet composition was homogenous between groups, we cannot support the hypothesis that a reduction in carbohydrates ingestion or the use of acarbose could prevent PPH. Nonetheless, when comparing people in special care facilities and people at home, the diet composition differences were significant when taking grams into account, but not regarding percentages, especially in breakfast. This finding supports other author's conclusions, but the different comparisons carried out did not show consistent results.24,30,33

The timing of the BP changes found in this study is consistent with the description of an increased mesenteric blood flow mediated by neurotensin N terminal from the minute 28±8 on, but there were no changes in the concentrations of glucagon, intestinal vasoactive peptide and neurokynin A.34–36 Our non-invasive study seems to support that the BP changes are the “simple” manifestation of a complex autonomic regulation of the mesenteric circulation in response to food ingestion.36

ConclusionsPost-prandial hypotension is highly prevalent without notorious demographic or history differences between groups. The group with significant PPH shows several significant differences as age, presence of dementia and hypertension and symptoms as drowsiness and general weakness. Patients living at the family home were less prone to show PPH, but they were also younger and healthier than those living in specialized care facilities.

The high prevalence of PPH in this population should promote different strategies toward a healthy diet and avoidance of fall risks in subjects with notorious post-prandial somnolence or weakness.

More studies are needed to establish if the worst cognition and quality of life scores are related with PPH or if they are the product of a deteriorated general health in which PPH is just another factor. The autonomic function needs to be better studied in the elderly population to clarify many of these questions.

FundingNo endorsement of any kind received to conduct this study/article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.