To assess the features of asymptomatic patients with acute ST segment elevation myocardial infarction who presents to the emergency with more than 12h of evolution, and if there is a benefit of an invasive versus medical therapy.

MethodsRetrospective, cohort study from January 2012 to December 2014, we compare the outcomes at 6 and 12 months of follow up of the invasive group versus the conservative group.

ResultsThere were no differences in outcomes at 12 months between an invasive versus a conventional strategy; but, looking at the reperfusion state, we found more risk of death and heart failure at 12 months in the no-reperfused group versus the reperfused group (40% versus 0%, OR: 2, CI: 1.2–3.1, p=0.028 for mortality and 53% versus 0%, OR: 2.2, CI: 1.3–3.98, p=0.007 for heart failure).

ConclusionsIn patients with ST elevation acute myocardial infarction with more than 12h of evolution, the invasive strategy with optimal reperfusion is better than the conservative management or no reperfusion in terms of less mortality and heart failure at 12 months of follow up.

Evaluar las características de pacientes con síndrome coronario agudo con elevación del segmento ST asintomáticos con más de 12 horas de evolución y si existe o no beneficio de la terapia invasiva versus el manejo médico en el seguimiento.

MétodoEstudio retrospectivo, de cohortes desde enero 2012 a diciembre 2014, se comparó los eventos adversos a 6 y 12 meses de seguimiento del grupo en terapia invasiva versus manejo conservador.

ResultadosNo se encontró diferencia entre la estrategia invasiva versus convencional al seguimiento a los 12 meses. Sin embargo comparando el resultado de reperfusión, se encontró mayor riesgo de muerte y falla cardiaca a 12 meses en el grupo no reperfundido versus el reperfundido (40% vs 0%, OR 2, IC: 1.2–3.1, p=0.028 para mortalidad y 53% vs 0%, OR: 2.2, IC: 1.3–3.98, p=0.007 para falla cardiaca).

ConclusionesEn pacientes con infarto agudo de miocardio ST elevado de más de 12 horas de evolución asintomáticos, la estrategia invasiva con resultados óptimos de reperfusión es mejor que el manejo conservador o no reperfusión en cuanto a disminución de la mortalidad y falla cardiaca en el seguimiento al año.

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the recommended treatment at the European and American guidelines for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) within the first 12h of symptoms onset.1 However, the benefit of revascularization after 12h in stable asymptomatic patients, without clinical, hemodynamic or electrical compromise, is still controversial. The definition of “early latecomers” refers to patients presenting between the 12 and 72h after symptoms onset2 and “latecomers” to those who come after 72h.

The ACC/AHA guidelines recommend performing PCI from 12 to 24h after symptoms onset, if there is clinical or electrocardiographic evidence of ischemia, as a IIa recommendation with a level of evidence B1; not giving any recommendation in case of stable patients or in those who arrive after 24h of onset of symptoms. The European guidelines recommend PCI beyond the 12h of symptoms onset, if there is evidence of ischemia (type of recommendation I, level of evidence C); but, also recommend the PCI in stable patients presenting between 12 and 24h (IIb-B).3 For both guidelines, PCI of a totally occluded infarct related artery (IRA) in stable patients after 24h of symptoms onset, has a recommendation III (contraindicated) with a level of evidence A.3

Globally, a significant proportion of patients attends health facilities after 12h of onset of symptoms; thus, in the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE registry) and in The randomized multicenter trial of Treatment with Enoxaparin and Tirofiban in Acute Myocardial Infarction (TETAMI) up to 40% of patients were “latecomers”.4,5

In the Peruvian reality and particularly in Lima city, few public medical centers have capacity for emergency coronary intervention. We do not have adequate and fast emergency transportation systems. Unfortunately, most patients don’t take into account the severity of symptoms from appearing, so expect plenty of time to go to a health facility or these are far from their homes. These two points means that a significant number of patients “lost” those first 12h to try to reperfuse the IRA. This registry seeks to determine the clinical, electrocardiographic and angiographic characteristics of the patients who come to the Instituto Nacional Cardiovascular – INCOR of the social security health system, just after 12h of symptoms onset, to analyze if there is any impact in IRA reperfusion after this time.

MethodsStudy populationWe include all patients over 18 years old, who were admitted to the Instituto Nacional Cardiovascular (INCOR) by the emergency service between January 2012 and December 2014, transferred from the different hospitals in the network of social health insurance (EsSALUD), with the diagnosis of STEMI whose onset of symptoms were between 12 and 72h before entering the hospital, with hemodynamic and electrical stability and without evidence of ongoing ischemia at admission (without angina). We excluded patients admitted for rescue PCI or pharmaco-invasive strategy, Also were excluded patients with hemodynamic compromise (Killip class III–IV), with ventricular arrhythmias, high grade atrioventricular block, post cardiac arrest, history of coronary artery bypass surgery or previous PCI and patients with history of myocardial infarction or heart failure.

We collected the clinical, ECG, echocardiographic and angiographic data from the medical records of the patients. For the electrocardiographic assessment we took into account the first ECG taken at admission, in which we assessed the presence or absence of pathological Q waves, negative or inverted T waves, and the myocardial area at risk (MaR) with the Selvester–Aldrich algorithms.6–11 To the echo-cardiographic assessment, we took into account the latest study before discharge from the index hospitalization or the last study before death. Also for the follow up, we contacted by phone for a new evaluation and echocardiographic study. The angiographic studies were reviewed from the digital files and the reports in the medical records.

Statistic analysisThe study has the characteristics of being an observational, retrospective cohort. We identified averages, frequencies, medias in the study population; using the chi-square test to compare categorical variables and the T-student test for continuous variables. Two sub-groups were compared: patients admitted to invasive strategy (coronariography) versus conservative strategy (medical treatment alone), and the state of revascularization (successfully revascularization with PCI<72h versus no revascularization). Calculating odds ratios and confidence intervals to 95% with SPSS version 13. Statistical significance was defined as a p value <0.05.

ResultsDuring January 2012 to December 2014, we found 44 patients (5.6% of all patients with STEMI) with more than 12h of evolution, whom met the inclusion criteria. Predominantly were men (35 patients, 79.5%), with an average age of 68 years old. Almost 90% came between 12 and 24h of symptoms onset and 11.3% (5 patients) between 24 and 72h.

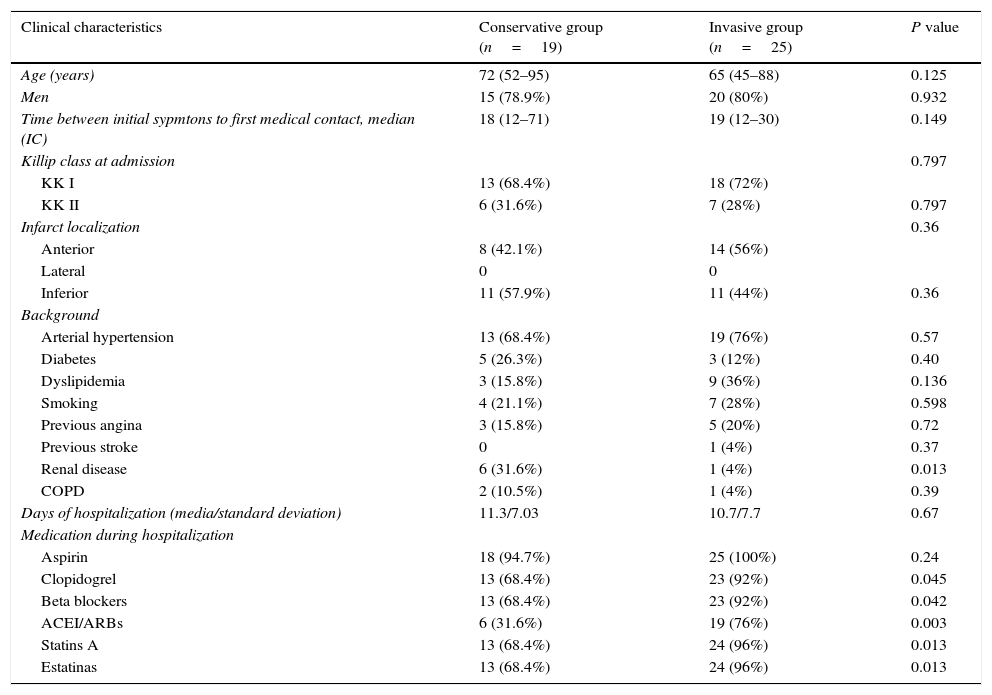

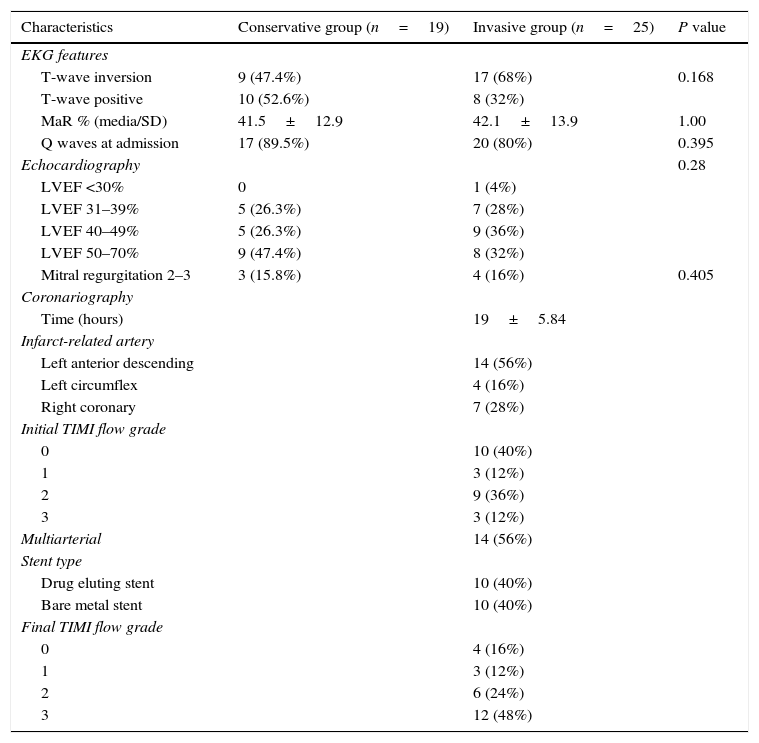

Clinical, angiographic, electrocardiographic and echocardiographic data of patients at hospital admission are summarized in Tables 1 and 2; comparing the population as initial management strategy of invasive versus conventional medical treatment.

Clinical features of patients according to the initial strategy. COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction, ACEI/ARBs: angiotensin-converting-enzime inhibitor/angiotensine II receptor blockers.

| Clinical characteristics | Conservative group (n=19) | Invasive group (n=25) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 72 (52–95) | 65 (45–88) | 0.125 |

| Men | 15 (78.9%) | 20 (80%) | 0.932 |

| Time between initial sypmtons to first medical contact, median (IC) | 18 (12–71) | 19 (12–30) | 0.149 |

| Killip class at admission | 0.797 | ||

| KK I | 13 (68.4%) | 18 (72%) | |

| KK II | 6 (31.6%) | 7 (28%) | 0.797 |

| Infarct localization | 0.36 | ||

| Anterior | 8 (42.1%) | 14 (56%) | |

| Lateral | 0 | 0 | |

| Inferior | 11 (57.9%) | 11 (44%) | 0.36 |

| Background | |||

| Arterial hypertension | 13 (68.4%) | 19 (76%) | 0.57 |

| Diabetes | 5 (26.3%) | 3 (12%) | 0.40 |

| Dyslipidemia | 3 (15.8%) | 9 (36%) | 0.136 |

| Smoking | 4 (21.1%) | 7 (28%) | 0.598 |

| Previous angina | 3 (15.8%) | 5 (20%) | 0.72 |

| Previous stroke | 0 | 1 (4%) | 0.37 |

| Renal disease | 6 (31.6%) | 1 (4%) | 0.013 |

| COPD | 2 (10.5%) | 1 (4%) | 0.39 |

| Days of hospitalization (media/standard deviation) | 11.3/7.03 | 10.7/7.7 | 0.67 |

| Medication during hospitalization | |||

| Aspirin | 18 (94.7%) | 25 (100%) | 0.24 |

| Clopidogrel | 13 (68.4%) | 23 (92%) | 0.045 |

| Beta blockers | 13 (68.4%) | 23 (92%) | 0.042 |

| ACEI/ARBs | 6 (31.6%) | 19 (76%) | 0.003 |

| Statins A | 13 (68.4%) | 24 (96%) | 0.013 |

| Estatinas | 13 (68.4%) | 24 (96%) | 0.013 |

Electrocardiographic, echocardiographic and angiographic characteristics according to the initial strategy. LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction MaR: myocardial area at risk.

| Characteristics | Conservative group (n=19) | Invasive group (n=25) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| EKG features | |||

| T-wave inversion | 9 (47.4%) | 17 (68%) | 0.168 |

| T-wave positive | 10 (52.6%) | 8 (32%) | |

| MaR % (media/SD) | 41.5±12.9 | 42.1±13.9 | 1.00 |

| Q waves at admission | 17 (89.5%) | 20 (80%) | 0.395 |

| Echocardiography | 0.28 | ||

| LVEF <30% | 0 | 1 (4%) | |

| LVEF 31–39% | 5 (26.3%) | 7 (28%) | |

| LVEF 40–49% | 5 (26.3%) | 9 (36%) | |

| LVEF 50–70% | 9 (47.4%) | 8 (32%) | |

| Mitral regurgitation 2–3 | 3 (15.8%) | 4 (16%) | 0.405 |

| Coronariography | |||

| Time (hours) | 19±5.84 | ||

| Infarct-related artery | |||

| Left anterior descending | 14 (56%) | ||

| Left circumflex | 4 (16%) | ||

| Right coronary | 7 (28%) | ||

| Initial TIMI flow grade | |||

| 0 | 10 (40%) | ||

| 1 | 3 (12%) | ||

| 2 | 9 (36%) | ||

| 3 | 3 (12%) | ||

| Multiarterial | 14 (56%) | ||

| Stent type | |||

| Drug eluting stent | 10 (40%) | ||

| Bare metal stent | 10 (40%) | ||

| Final TIMI flow grade | |||

| 0 | 4 (16%) | ||

| 1 | 3 (12%) | ||

| 2 | 6 (24%) | ||

| 3 | 12 (48%) | ||

The initial strategy at patient admission was mostly invasive in 56.8% (25 cases), which entered catheterization laboratory in 80% between 12 and 24h of onset of symptoms. The 43.2% of patients received conservative medical management.

In the conservative treatment group (19 cases); 11 patients (57%) were tested for evaluation of ischemia before discharge (with eco-stress or SPECT). These test were negatives or with low ischemic risk in 7 of them (63%), so they were discharged without further intervention; in 1 case (5.2%) the result was positive, so an angioplasty was performed with more than 72h after symptoms onset; three cases (15.7%) underwent CABG after evaluation of ischemia and three patients (15.7%) died in the hospital before doing any study of ischemia.

We found that only 12 of 25 patients in the invasive group (48%) had successful reperfusion. In 6 patients (24%) the result of angioplasty was TIMI flow 2 and in 5 patients (20%) the final TIMI flow of the IRA was 0–1. The remaining 8% of patients were scheduled for surgical revascularization.

We observed in the total study population 4 cases of hospital death (9.09%), 2 cases of recurrent angina (4.5%), 1 case of ischemic stroke (2.2%), 5 cases of heart failure (11.4%) and 3 cases of cardiogenic shock (3%) during hospitalization.

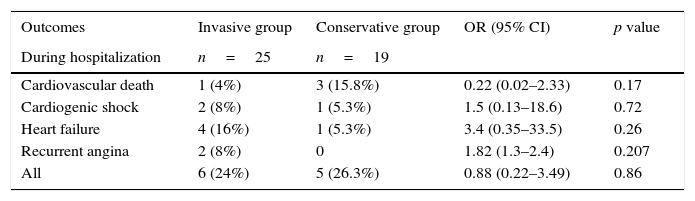

In-hospital cardiovascular mortality in the conservative group was 15.8% (3 patients) versus 4% (1 patient) in the invasive group; being the free ventricular wall rupture, the cause of death in the 3 patients in the conservative group and refractory cardiogenic shock in the invasive group. In the case of inpatient recurrent angina, it occurred in 2 patients: one after frustrated PCI and the second after successful PCI of the IRA but with ischemia in other coronary territory corroborated by changes in the EKG. Increased frequency of heart failure and cardiogenic shock was also found during hospitalization in the invasive group, although those cases occurred in patients with frustrated PCI and with surgical management after 72h of evolution. In the follow up to 1 year, we found no difference in the rate of adverse events between the two groups as shown in Table 3; note that no cases of myocardial re-infarction or new revascularization occurred in either group.

Cumulative incidence of cardiovascular death, cardiogenic shock, heart failure and recurrent angina for conservative and invasive strategy groups. CI: confidence interval, OR: odds ratio.

| Outcomes | Invasive group | Conservative group | OR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| During hospitalization | n=25 | n=19 | ||

| Cardiovascular death | 1 (4%) | 3 (15.8%) | 0.22 (0.02–2.33) | 0.17 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 2 (8%) | 1 (5.3%) | 1.5 (0.13–18.6) | 0.72 |

| Heart failure | 4 (16%) | 1 (5.3%) | 3.4 (0.35–33.5) | 0.26 |

| Recurrent angina | 2 (8%) | 0 | 1.82 (1.3–2.4) | 0.207 |

| All | 6 (24%) | 5 (26.3%) | 0.88 (0.22–3.49) | 0.86 |

| At 6 months | n=20 | n=12 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular death | 2 (10.5%) | 3 (27.3%) | 0.31 (0.043–2.26) | 0.236 |

| Heart failure | 4 (20%) | 1 (8.3%) | 1.35 (0.78–2.31) | 0.379 |

| Recurrent angina | 2 (10.5%) | 0 | 1.6 (1.2–2.2) | 0.265 |

| All | 5 (25%) | 4 (33.3%) | 0.85 (0.44–1.64) | 0.612 |

| At 12 months | n=15 | n=9 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular death | 2 (13.3%) | 4 (44.4%) | 0.46 (0.144–1.48) | 0.088 |

| Heart failure | 4 (26.7%) | 4 (44.4%) | 0.72 (0.33–1.56) | 0.371 |

| Recurrent angina | 2 (13.3%) | 2 (22.2%) | 0.76 (0.27–2.15) | 0.572 |

| All | 5 (33.3%) | 5 (55.6%) | 0.70 (0.34–1.41) | 0.285 |

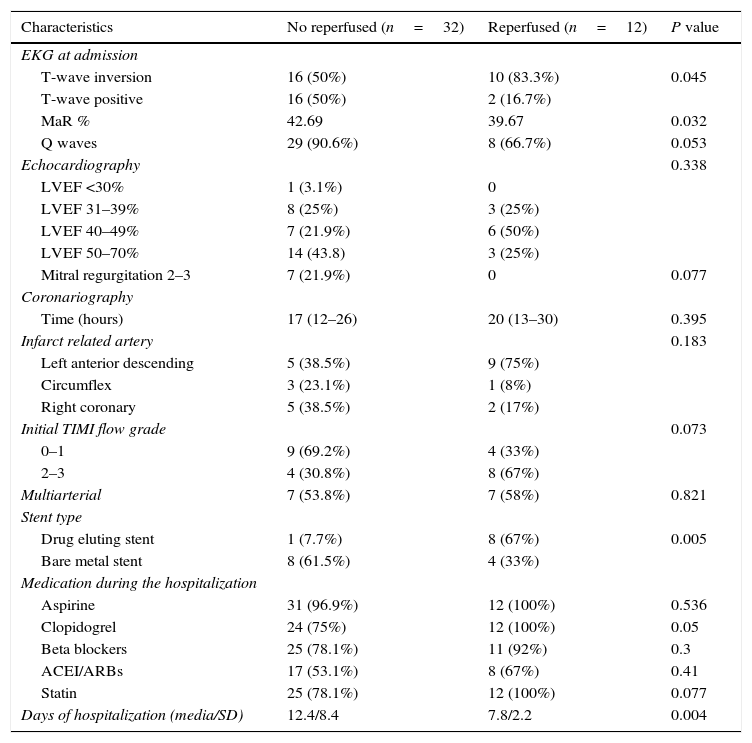

Because more than half of patients in the invasive group had angiographic results of reperfusion under TIMI flow 3, we decided to compare the group with successful invasive strategy (TIMI flow 3 post PCI) calling them “reperfused”, versus the rest of patients “not-reperfused”; these latter include patients with conservative management, with final TIMI flow of IRA <3 or with surgery revascularization past 72h of symptoms onset; their baseline data are shown in Table 4. Thus, we found that 72.7% of patients were not reperfused (32 cases) and only 27.3% (12 cases) were successfully reperfused with PCI.

Electrocardiographic, echocardiographic and angiographic characteristics according to reperfusion status. MaR: myocardial area at risk, LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction, ACEI/ARBs: angiotensin-converting-enzime inhibitoR/Angiotensine II receptor blockers.

| Characteristics | No reperfused (n=32) | Reperfused (n=12) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| EKG at admission | |||

| T-wave inversion | 16 (50%) | 10 (83.3%) | 0.045 |

| T-wave positive | 16 (50%) | 2 (16.7%) | |

| MaR % | 42.69 | 39.67 | 0.032 |

| Q waves | 29 (90.6%) | 8 (66.7%) | 0.053 |

| Echocardiography | 0.338 | ||

| LVEF <30% | 1 (3.1%) | 0 | |

| LVEF 31–39% | 8 (25%) | 3 (25%) | |

| LVEF 40–49% | 7 (21.9%) | 6 (50%) | |

| LVEF 50–70% | 14 (43.8) | 3 (25%) | |

| Mitral regurgitation 2–3 | 7 (21.9%) | 0 | 0.077 |

| Coronariography | |||

| Time (hours) | 17 (12–26) | 20 (13–30) | 0.395 |

| Infarct related artery | 0.183 | ||

| Left anterior descending | 5 (38.5%) | 9 (75%) | |

| Circumflex | 3 (23.1%) | 1 (8%) | |

| Right coronary | 5 (38.5%) | 2 (17%) | |

| Initial TIMI flow grade | 0.073 | ||

| 0–1 | 9 (69.2%) | 4 (33%) | |

| 2–3 | 4 (30.8%) | 8 (67%) | |

| Multiarterial | 7 (53.8%) | 7 (58%) | 0.821 |

| Stent type | |||

| Drug eluting stent | 1 (7.7%) | 8 (67%) | 0.005 |

| Bare metal stent | 8 (61.5%) | 4 (33%) | |

| Medication during the hospitalization | |||

| Aspirine | 31 (96.9%) | 12 (100%) | 0.536 |

| Clopidogrel | 24 (75%) | 12 (100%) | 0.05 |

| Beta blockers | 25 (78.1%) | 11 (92%) | 0.3 |

| ACEI/ARBs | 17 (53.1%) | 8 (67%) | 0.41 |

| Statin | 25 (78.1%) | 12 (100%) | 0.077 |

| Days of hospitalization (media/SD) | 12.4/8.4 | 7.8/2.2 | 0.004 |

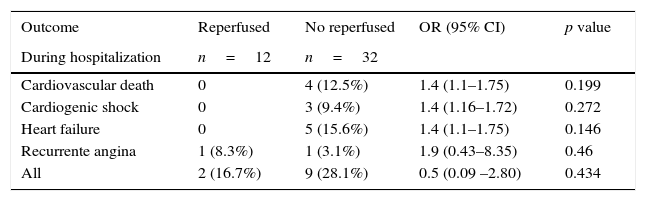

The adverse events by reperfusion state are shown in Table 5. Increased incidence of cardiovascular death was found in the not reperfused group with statistical significance at one year of follow up and nor before this time. Likewise, the incidence of heart failure was higher in the not reperfused group. Overall, the successful invasive strategy correlates with reduced mortality and heart failure at 1 year of follow up.

Cumulative incidence of cardiovascular death, cardiogenic shock, heart failure and recurrent angina according to reperfusion. CI: confidence interval, OR: odds ratio.

| Outcome | Reperfused | No reperfused | OR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| During hospitalization | n=12 | n=32 | ||

| Cardiovascular death | 0 | 4 (12.5%) | 1.4 (1.1–1.75) | 0.199 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 0 | 3 (9.4%) | 1.4 (1.16–1.72) | 0.272 |

| Heart failure | 0 | 5 (15.6%) | 1.4 (1.1–1.75) | 0.146 |

| Recurrente angina | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (3.1%) | 1.9 (0.43–8.35) | 0.46 |

| All | 2 (16.7%) | 9 (28.1%) | 0.5 (0.09 –2.80) | 0.434 |

| At 6 months | n=11 | n=21 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular death | 0 | 5 (26.3%) | 1.7 (1.2–2.5) | 0.062 |

| Heart failure | 0 | 5 (26.3%) | 1.6 (1.23–2.3) | 0.078 |

| Recurrent angina | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (5.3%) | 1.4 (0.3–6.1) | 0.685 |

| All | 1 (9.1%) | 8 (38.1%) | 0.25 (0.038–1.71) | 0.083 |

| At 12 months | n=9 | n=15 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular death | 0 | 6 (40%) | 2 (1.2–3.17) | 0.028 |

| Heart failure | 0 | 8 (53.3%) | 2.2 (1.3–3.98) | 0.007 |

| Recurrent angina | 1 (11.1%) | 3 (20%) | 0.62 (0.10–3.70) | 0.572 |

| All | 1 (11.1%) | 9 (60%) | 0.175 (0.026–1.18) | 0.019 |

In the case of the relationship between electrocardiographic findings on admission and the patency of the IRA before the PCI in the invasive group; we found, that the presence of negative or inverted T waves in leads with ST-segment elevation on the first EKG was correlated with an open IRA (TIMI flow 2–3) in the 64.7% of cases, while the presence of positive T waves was correlated with an occluded IRA (TIMI flow 0–1) in 87.5% of cases (p=0.015). Also we note that the presence of negative T waves in the EKG was associated with the success of the PCI; thus, 58.8% of patients with inverted T waves had successful reperfusion (TIMI flow grade 3 post PCI); while 75% of patients with positive T waves had unsuccessful reperfusion (TIMI flow grade 0–2) (p=0.114).

In patients with occluded IRA: 46% had TIMI flow grade 2–3 after PCI, but 53.8% remained occluded. But the 100% of patients with open IRA had good results after PCI (TIMI flow 3) (p=0.003; OR: 0.462; CI: 0.25–0.83). In this group of occluded IRA that remained occluded after PCI: 3 patients (42.9%) had in-hospital adverse events versus 0% if the IRA was opened (p=0.067; OR: 0.57; CI: 0.3–1.08).

A 38.8% of patients in the invasive group with less than 24h of symptoms onset had open IRA. Of this group 85% remained with IRA TIMI flow grade 3 after PCI and 15% (1 patient) with TIMI 2. There were no adverse events on the follow up of this subgroup. The remaining 60.2% of the invasive group with less than 24h of symptoms onset had occluded IRA. Of this group 27.2% had TIMI flow 3 after PCI with no adverse events at 1 year follow up, unlike the group that stayed with TIMI flow grade <3 post PCI, where 45% of patients experienced adverse events.

The myocardial area at risk (MaR) evaluated by Selvester–Aldrich score was 41.87±13.3 in the total population. The average in the not reperfused group was higher than the reperfused group, denoting larger area at risk in the first group (42.6% versus 39.6%; p=0.032).

The left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) at 1-year follow up was 52.8% in the invasive group and 47.6% in the conservative group (p=0.186). In the reperfused group was 55.5% versus 45.5% in the not reperfused group (p=0.188).

The hospital stay in the invasive group was slightly lower than in the conservative group (10.7 versus 11.3 days; CI: −5.5 to 4.4; p=0.674); however, the hospital stay in the reperfused group was significantly lower than the not reperfused group (7.8 versus 12.4 days; CI: −8.13 to −1.01; p=0.004).

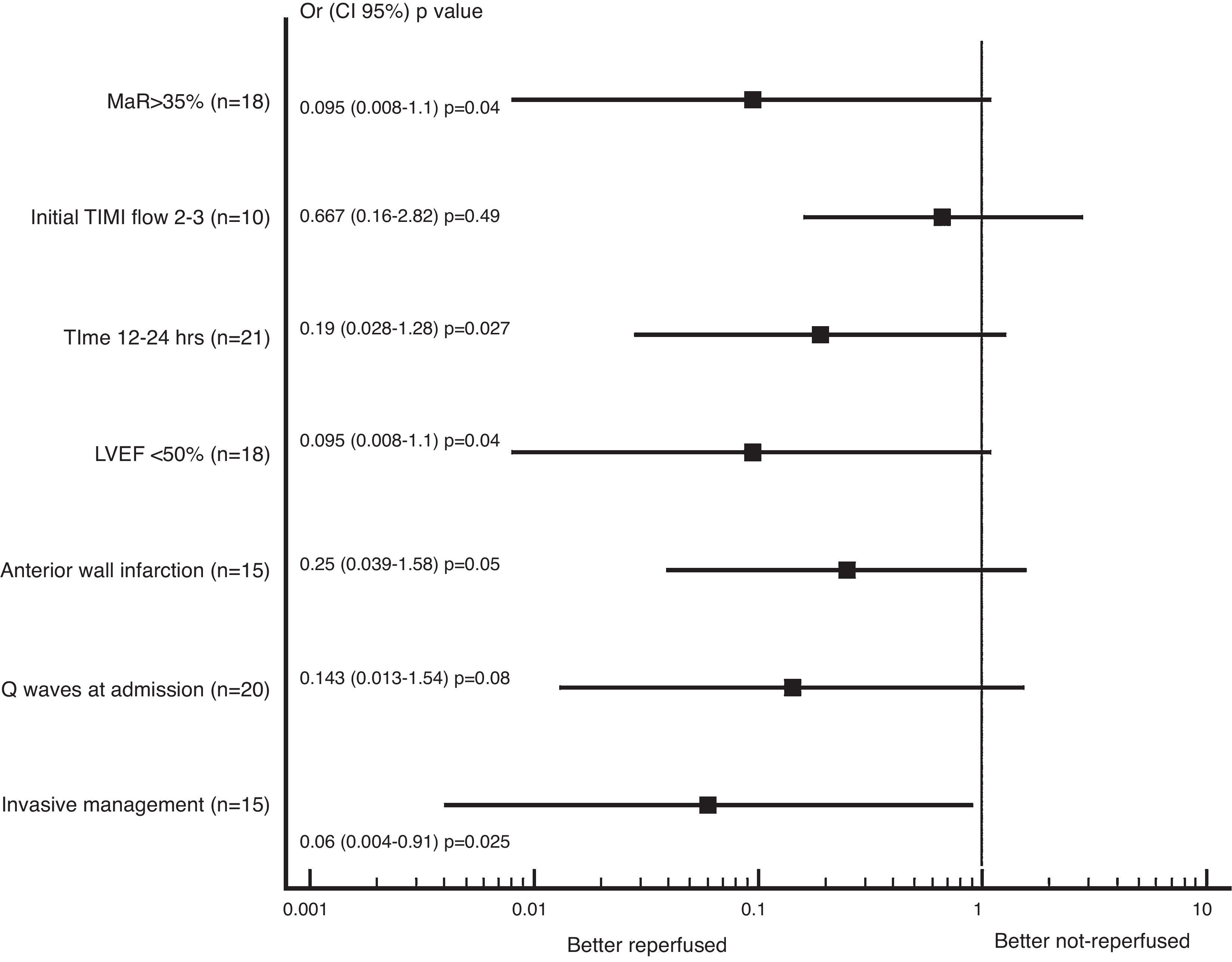

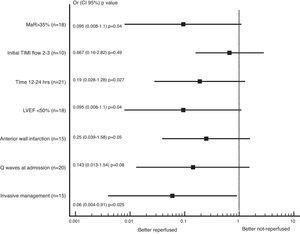

In the subgroup analysis that the literature mentioned as markers of increased risk; we found trend to less adverse events (combined cardiovascular death, heart failure or recurrent angina) in the reperfused group; being the patients with successful reperfusion in the invasive group whom had less adverse events at 1 year of follow up (OR 0.063, CI: 0.004–0.915, p=0.025), as presented in Fig. 1.

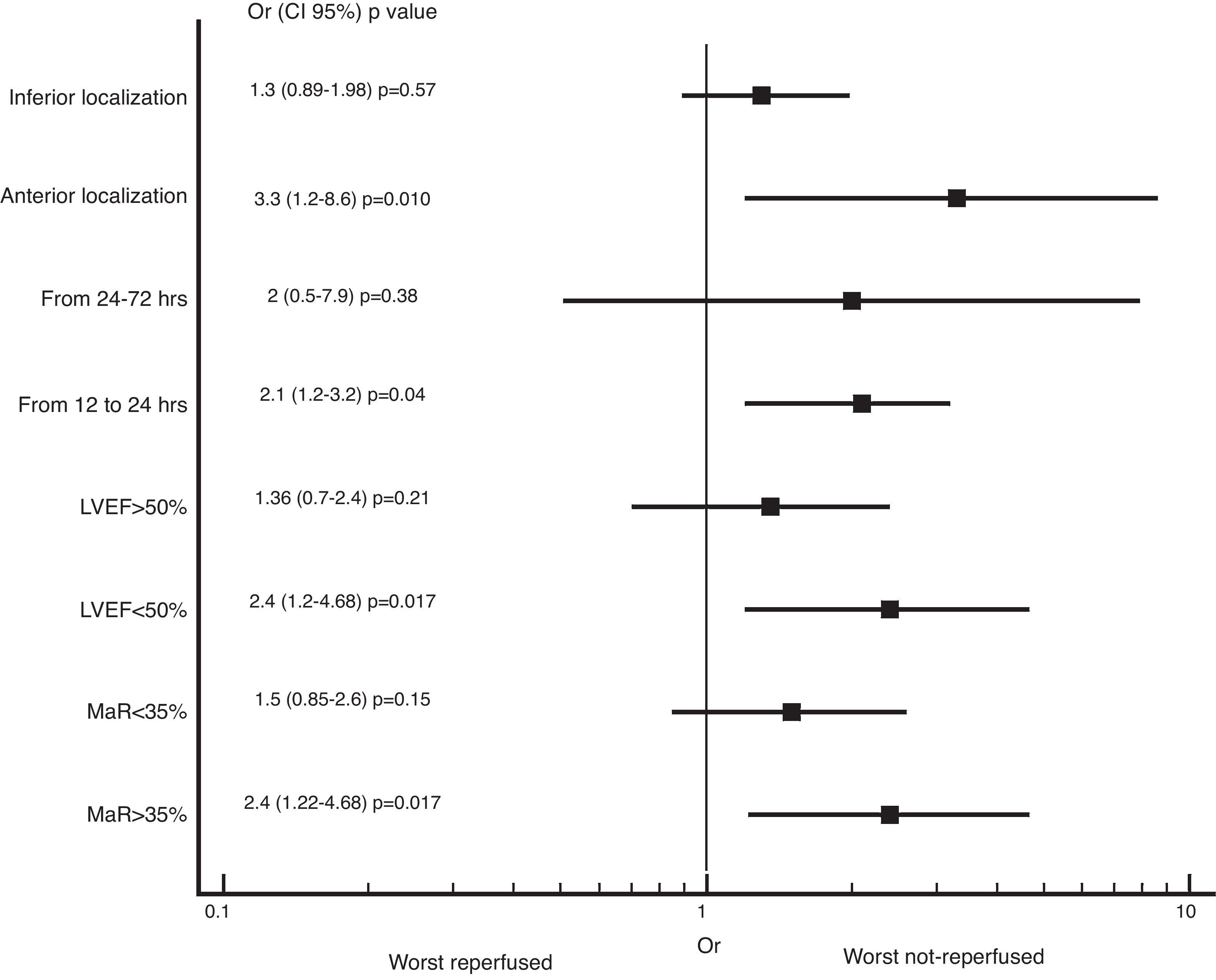

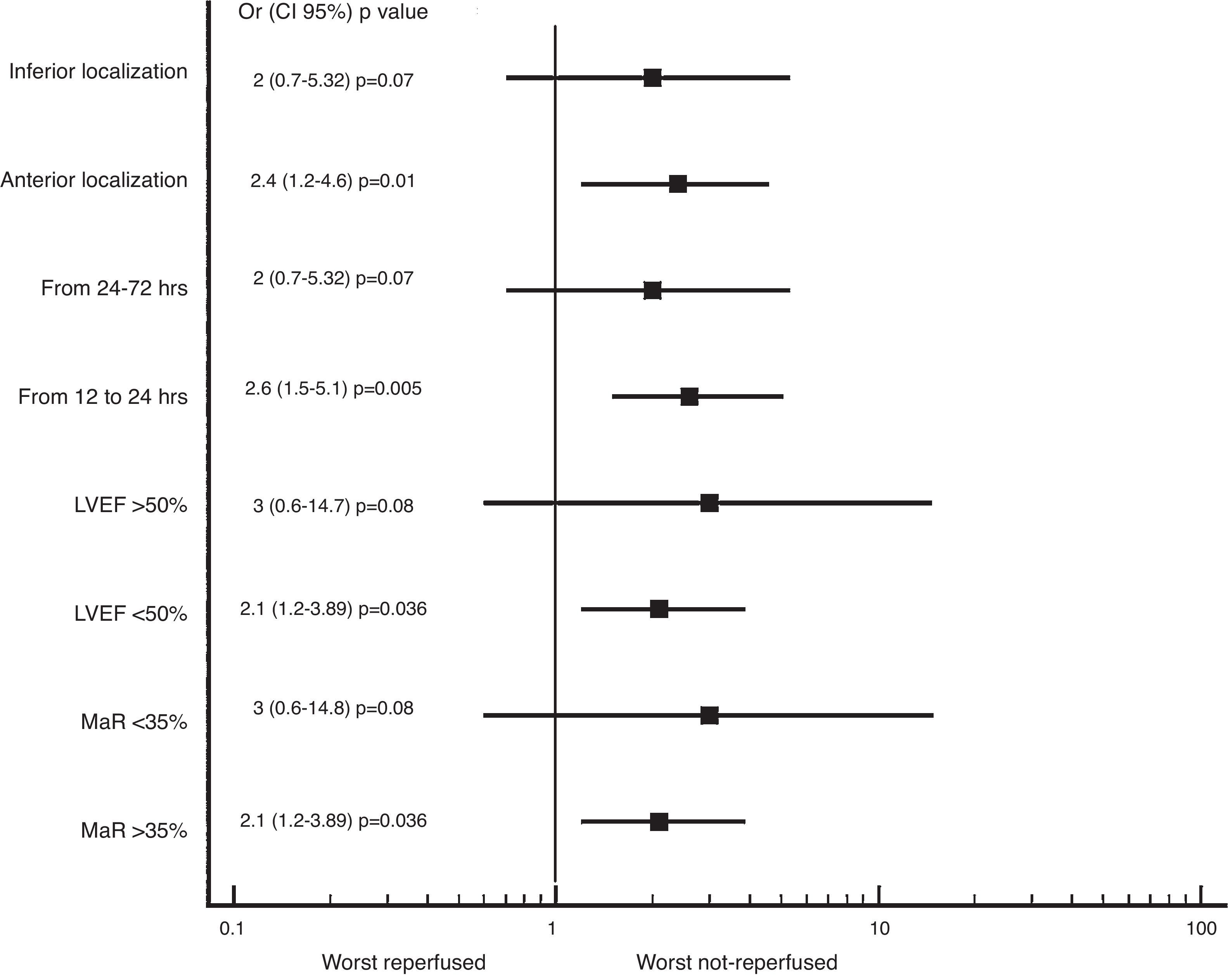

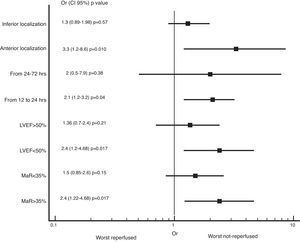

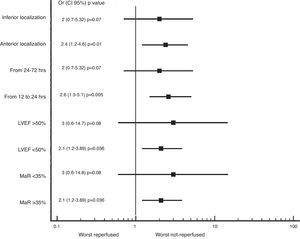

We also found greater benefit in terms of mortality and heart failure at 1 year follow-up in the reperfused group; especially in patients with MaR >35%, with PCI between 12 and 24h, with compromise of the anterior wall or with LVEF below 50%, as shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

We studied 44 “early latecomers” STEMI patients, whom went asymptomatic to the Instituto Nacional Cardiovascular INCOR of the national health social security of Perú between 12 and 72h of symptom onset during the years 2012–2014. We found that this patient group represents 5.6% of all STEMI patients registered during that period. In the 56.8% of cases are handled with immediately invasive coronary angiography; this group showed occluded IRA in 52% and TIMI flow grade 3 in 48% pre PCI. Draws attention to the low success rate of PCI in this group due to the no-reflow phenomenon and distal embolization. In accordance with international studies5 we found that the IRA most frequently affected was the left anterior descending (56%), patients with estimated creatinine clearance <50mg/dl were more likely to receive conservative management and that the use of double antiplatelet therapy, beta-blockers, ACEI and statins was lower in patients with conservative strategy. In-hospital mortality was higher in the conservative group with 3 cases of free wall rupture and electromechanical dissociation, but did not reach statistical significance. As for the higher frequency of in-hospital heart failure, recurrent angina and cardiogenic shock in the invasive group, it should be emphasized that these cases occurred in patients with frustrated angioplasty (not reperfused). At follow-up at 6 and 12 months, no significant differences in mortality, heart failure or recurrent angina was seeing between invasive or conservative group.

Considering that 52% of patients in the invasive group had suboptimal results of PCI, they were considered not reperfused adding them to patients in conventional treatment. Thus we found that in the reperfused group was more frequently founded absence of Q waves and presence of inverted T waves in the EKG. Greater frequency of open IRA, better use of medication (double antiplatelet drugs, beta-blockers and statins) and shorter hospital stay. In terms of adverse events it was found that the group of reperfused patients had less mortality and heart failure at 12 months follow-up. Because of the retrospective nature of the study, the small size of the population and the loss of patients in the follow-up that reached a 45% loss of sample volume per year, the conclusions in terms of reduction in mortality and heart failure should be taken with care, although the downward trend is clear in the reperfused group, these data should be corroborated with larger and specially randomized studies.

International studies like Schömig et al.,12 who studied 365 “early-latecomers” stable patients with STEMI whom presented after 12–48h of symptoms onset, half randomized to immediate angiography followed by PCI and half randomized to conservative medical management; demonstrated with the use of computed tomography with single photon emission (SPECT) a reduced infarct size by approximately 7% with the use of PCI versus conservative management. No significant differences were found in the secondary end points (death, recurrent infarct or stroke) at 30 days. Important to note in this study that only 37% of patients had anterior wall infarction in both groups. The KAMIR registry13 evaluated 2640 “early latecomers” stable patients who presented to medical services between 12 and 72h of onset of symptoms, which were randomized to PCI (programmed with an average of 23h after randomization in 86% of cases), versus conservative management. They found a decrease in hospital mortality (1.7% versus 5.3%) in the invasive group; with increased survival free of death and myocardial infarction at 12 months. Subgroup analysis showed that the invasive strategy was better in patients with IRA initial TIMI flow grade 2–3 than the TIMI flow grade 0–1 subgroup, but showed no statistical significance (RR 0.65, CI: 0.25–1.7). Our study shows that patients with open IRA pre-PCI are more likely to be reperfused (TIMI 3) and that this entails less risk of adverse events.

Hochman et al. for the Occluded Artery Trial (OAT)14 studied 2166 stable latecomers patients with occluded IRA between 3 and 28 days post myocardial infarction, with LVEF <50% or proximal coronary occlusion, which were randomized to PCI versus conventional therapy; they found that PCI did not reduce the occurrence of death, heart attack or heart failure at 4 years of follow-up compared to conventional treatment.

Abbate et al.15 in their meta-analysis of 10 controlled and randomized studies of latecomers patients with PCI past 12h of symptoms onset, conclude that there is an advantage in terms of survival and cardiac remodeling post myocardial infarction in patients who undergo PCI of the IRA versus conservative management; being the average time from onset of symptoms to PCI of 12 days, with ranges as short as one day in BRAVE-2 trial to as long as 26 days in the SWISSI II trial. One of the most significant data was the greatest benefit of invasive treatment in studies with over 4 years of follow-up, suggesting better influence of PCI on peri-infarction myocardial damage, preventing the apoptosis of the hibernated myocardium.16

In our study we found that the presence of inverted T waves was related in 64% with an open IRA, so that the presence of inverted T waves can serve as an additional criterion for stratification of patients to choose an invasive strategy with a view to successful revascularization; this is also supported by the higher frequency of successful PCI if the initial flow of the IRA is TIMI flow grade 2–3. Similarly, Hira et al.16 studied 146 patients with STEMI of less than 12h of evolution and divided them into those with inverted T waves (>0.5mV) in leads with elevated ST segment and those who had positive T waves, finding that the presence of inverted T waves related by almost 70% with patent IRA in anterior wall infarctions and in 20% in inferior wall infarctions. On the contrary the presence of positive T waves was associated with an 80% of cases with occluded IRA without differences in the localization of the infarction. Similar to those data obtained by Alsaab y cols.17 where the presence of inverted T waves was related to IRA patency in 64% of patients with anterior wall infarction, versus 81% of patients with positive T waves, whom had an occluded IRA, specially in anterior wall infarction (90%).

Other authors like Acet et al.18 had found that some biomarkers may be related to a patent IRA, as for example the ratio platelets/lymphocyte >190, uric acid >5.75mg/dl and the ratio neutrophil/lymphocyte >4.2 that could predict an IRA TIMI flow grade less than with a specificity of 88% and sensitivity of 84% for the first one; the same authors support their findings in the relationship of greater platelet reactivity and inflammation with no patency of the IRA.

Zhang et al. evaluated the association of the myocardial area at risk (MaR) measured by the Selvester–Aldrich score on the EKG and cardiovascular death, re-infarction and revascularization at 2 years in 436 latecomers patients randomized to PCI or conservative management. They found that those patients with MaR >35% that underwent PCI had lower incidence of the composite endpoint described above, which is not evident in patients with MaR <35%.5

With the results described, we can see that there is still benefit of revascularization of the IRA beyond the 12h of evolution, the greatest benefit is in patients between the 12 and 24h of evolution, with TIMI flow grade 2–3 pre PCI, with inverted T waves in the first EKG at admission and events that involve the anterior wall. Is important to take all necessary measures in the catheterization laboratory to ensure proper post-PCI patency of the IRA, since this factor is what made the difference into the invasive group with the lowest incidence of adverse events in the follow-up.

Given that public health services and social security in Peru are not quickly and optimally available to the population due to remoteness of the health centers to the people homes, to lack of information of the population in recognizing myocardial infarction symptoms quickly and due to problems of medical care like lack of training in primary care levels to recognize changes suggestive of STEMI in the EKG or simply lack of electrocardiographs; the number of patients presenting with more than 12h of evolution to public hospitals or hospitals of the social security, may be higher than of the present study, so we have an opportunity to decrease the adverse events in the follow-up of this patients with an optimal revascularization.

Study limitations are related to the small population size, limited to one hospital, the type of the study (retrospective, non-randomized) and the low percentage of patients in the 12 months follow-up, which reduces its external validity.

ConclusionsIn asymptomatic patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction with more than 12h of evolution entering to the Instituto Nacional Cardiovascular INCOR in Lima – Peru; the invasive strategy with good reperfusion results is better than conservative management or no reperfusion in terms of reduction of mortality and heart failure at 12 months follow-up.

The presence of inverted T waves in the EKG, the time of evolution between 12 and 24h, the anterior wall infarction or the LVEF <50% are parameters that can orient the physician to prefer an invasive strategy with a view to successful reperfusion.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.