el estudio HHS (1987) del 10,6%, y en el estudio LRC-CPPT (1984) del 2,4%. Conclusiones. Un gran número de nuestros pacientes (97-54%) con dislipemia no serían incluidos en los estudios de hiperlipidemia y prevención primaria. Comprobamos que la validez externa (aplicabilidad a la población general) de estos estudios es cuestionable. La toma de decisiones en la práctica clínica de la prevención primaria en la hipercolesterolemia deberá basarse en la relación riesgo/beneficio de la introducción de un fármaco.

Introduction

Dyslipidemia is a well established risk factor for cardiovascular disease. In 1998, ischemic heart disease in Spain was the most frequent cause of death in men and the third most frequent cause of death in women.1 Different studies have shown the treatment of dyslipidemia to be useful in the secondary prevention of ischemic coronary heart disease.

However, questions have arisen regarding the usefulness of primary prevention in the general population.2 Treatment for dyslipidemia in patients with no antecedents of coronary heart disease has been the subject of debate, and physiopathological, epidemiological, ethnicity and cost-effectiveness considerations have been used to argue in favor of and against such treatment.

Well-performed clinical trials have a high degree of internal validity, but their external validity for the general population has been questioned. The criteria used to select patients for large trials of the primary prevention of hypercholesterolemia have been highly restrictive in terms of age, lipid levels, sex, and concomitant diseases such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus.

Currently, the five most important trials of primary prevention of ischemic heart disease are the Lipids Research Clinics Coronary Prevention Trial (LRC-CPPT, 1984),3 the Helsinki Heart Study (HHS, 1987),4 the West Scotland Coronary Prevention Study (WOSCOPS, 1995),5 the Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study (AFCAPS/TexCAPS, 1998)6 and the Heart Protection Study (HPS, 2002).7 This latter trial included patients with and without coronary heart disease.

These studies have documented reductions of 19% to 37% in the risk of primary cardiovascular events or mortality from coronary heart disease as a result of lipid-lowering therapy in comparison to a placebo. However, the inclusion criteria in these studies are in general inappropriate for the general population, and are usually circumscribed to patients at high risk for cardiovascular disease. For example, women were included in only two of these trials (AFCAPS/TexCAPS6 and HPS7).

In one recent analysis (Lloyd-Jones, et al, 2001)8 based on the population used in the Framingham9 study, between 20% and 80% of the participants would not have been eligible for inclusion in any of the primary prevention studies done to date. Thus the applicability of the results of these studies to actual clinical practice is, to some extent, debatable.

The main objective of our study was to determine the degree of external validity of the clinical trials mentioned above for the population under our care, by determining the degree of similarity between the sample populations used in these studies and the population of persons with dyslipidemia in our setting.

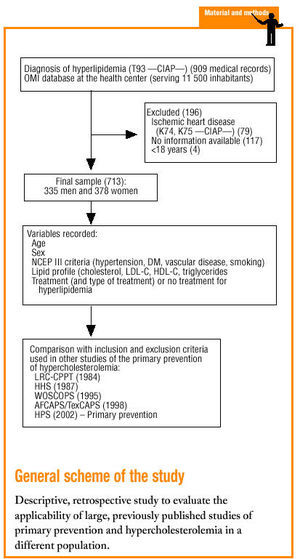

Material and methods

The study was done in the Tafalla basic health care area (Navarra province, Northern Spain), which serves a population of approximately 11 500.

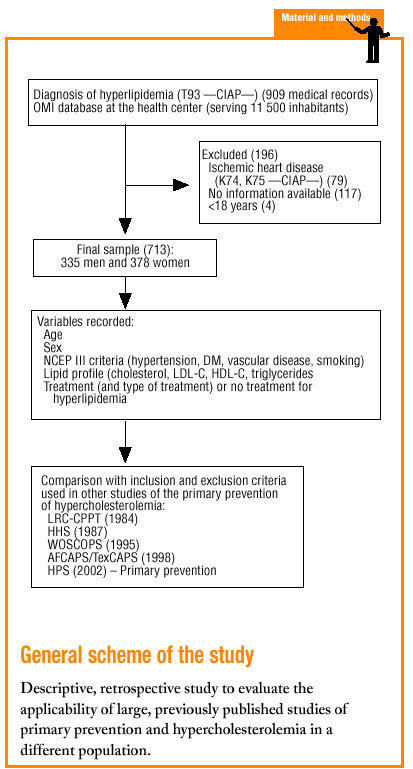

We selected patients older than 18 years with a diagnosis of hyperlipidemia (Clasificación Internacional de Atención Primaria [CIAP] code T93) and registered in the OMI database of clinical histories, who had no personal antecedents of cardiovascular disease, i.e., acute myocardial infarction (CIAP code K74) or angina (CIAP code K75), and who were therefore eligible for primary prevention. When necessary, clinical histories recorded on paper only were used. The two exclusion criteria were any cardiovascular event (AMI or angina) before dyslipidemia had been diagnosed, and unavailability of lipid profile data obtained before treatment was begun.

Sociodemographic data were noted for age, sex, year of birth, and year of diagnosis of hyperlipidemia. Clinical data were recorded for total, HDL-C and LDL-C, triglycerides, weight, height and body mass index (BMI, kg/m2). We also recorded whether pharmacological treatment was prescribed to lower cholesterol levels, and the drug used (simvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, atorvastatin, fluvastatin, fibrates, other).

The risk factors chosen for analysis were based on NCEP III10 criteria (Table 1), currently considered the most reliable for clinical decision-making.

For patients whose cholesterol levels were being treated pharmacologically, we recorded as the lipid profile values the earliest results entered in the medical record before treatment was begun. For patients who were not taking any lipid-lowering medication, we recorded the most recent values obtained during the previous 6 months.

A specially-designed database was used to compare the inclusion criteria in 5 earlier studies of the primary prevention of ischemic heart disease: LRC-CPPT (1984),3 HHS (1987),4 WOSCOPS (1995),5 AFCAPS/TexCAPS (1998),6 HPS(2002)7 (Table 2).

For all statistical analyses we used version 10 of the SPSS.

Results

We reviewed 909 medical records and included 713 in the analysis. Of the 196 records we excluded, 79 recorded at least one cardiovascular event, 117 lacked data on cholesterol levels before treatment was begun, and 4 were for patients younger than 18 years. Of the 731 records included, 335 were for men (47%) and 378 (53%) were for women. Mean age±SD was 61±13.7 years.

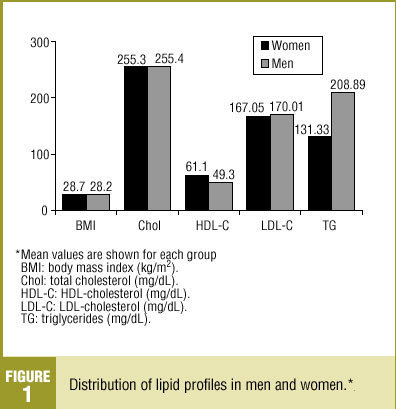

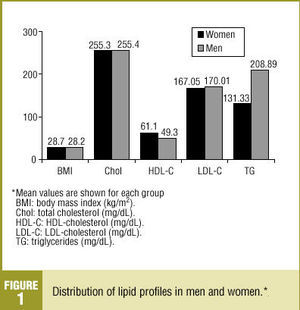

Total cholesterol level (mean±SD) was 255.04±37.4 mg/dL, with no significant difference between men and women (Figure 1). HDL-C level (mean±SD) was 55.7±16.2 mg/dL, and was higher in women (61.1±16 mg/dL). Notably, the HDL-C level was higher than 50 mg/dL in 60.4% of our sample. The LDL-C level (mean ±SD) was 168.4±35.1 mg/dL, with no significant difference between sexes. Triglyceride levels (mean±SD) were higher in men (208.9±177.2 mg/dL) than in women (131.33±72 mg/dL).

Figure 1. Distribution of lipid profiles in men and women.

Of the patients with a diagnosis of hyperlipidemia, 38.8% were taking lipid-lowering drugs. The most frequently used drug was atorvastatin (27.4%), followed by simvastatin (22.4%) and lovastatin (20.2%).

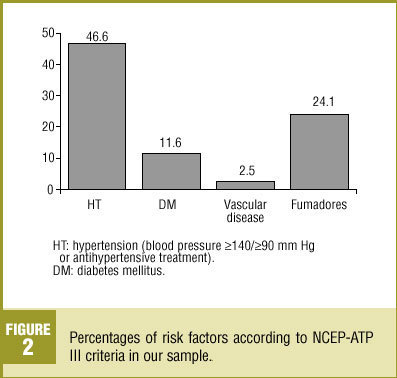

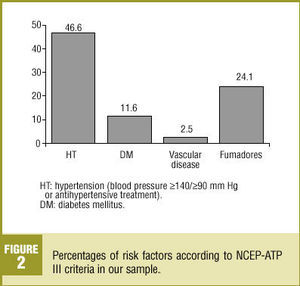

Nearly half (46.6%) of the patients in our analysis had hypertension (>=140/>=90 mm Hg) or were taking medication to lower blood pressure (Figure 2); 52.2% of these patients were women. Diabetes mellitus (DM) was recorded in 11.6% of the sample. Vascular disease was recorded in 2.5% of the medical records we reviewed. About one-fourth (24.1%) of the patients were smokers, 7.2% were ex-smokers and 51.2% had never been smokers; no information on smoking habit was recorded in the remainder of the medical records we reviewed. About three-fourths (72.5%) of the patients were overweight, with a mean BMI±SD of 28.5±4.3 kg/m2.

Figure 2 . Percentages of risk factors according to NCEP-ATP III criteria in our sample.

The characteristics of our sample were compared with those of the population from the Framingham study9 and earlier primary prevention studies (Table 3). Of note was the higher percentage of men with hypertension in our sample (40.0%) in comparison to other studies, the higher percentage of persons with DM (11.3%) in our sample, and the higher mean level of HDL-C. Among women included in the samples we compared, mean age was higher in our sample (65 years), as was total cholesterol level (mean±SD, 255±34 mg/dL), HDL-C (61±16 mg/dL), the percentage of women with DM (11.9%) and the percentage of women with hypertension (52.5%).

The percentage of our sample that satisfied the inclusion criteria used in each of the earlier primary prevention studies is shown in Table 4. This percentage was highest for the AFCAPS/TexCAPS study6 (46.2%), followed in decreasing order by the HPS7 (46.1%), the WOSCOPS5 (10.9%), the HHS4 (10.6%), and the LRC-CPPT study3 (2.4% of the population).

Discussion

The selection criteria used in different primary prevention studies of hypercholesterolemia published to date do not reflect the realities of daily practice for patients seen in our primary care service. In other words, the internal validity (degree to which the results of a given study reflect the actual status of the population under study) has been well established. However, the external validity (degree to which the results of a given study can be generalized to other individuals) is questionable.

Of the large trials published to date, those that come closest to reflecting the characteristics of the population of patients with dyslipidemia in our setting are the AFCAPS/TexCAPS6 and the HPS,7 for which we found a concordance of 46%. The other studies (WOSCOPS5, HHS4 and LRC-CCPT3) yielded a concordance of only 2% to 10%. These figures are similar to the results reported by Lloyd-Jones, et al8 in their analysis of the population used for the Framingham study9. These authors found that 40% of the men and 80% of the women with dyslipidemia were missed by these large hyperlipidemia studies.

It should be recalled that in large studies of primary prevention and hyperlipidemia, the participants included for analysis were generally persons who had not yet had any cardiovascular event, although they were at high risk for such events. In other words, the most frequently chosen participants were middle-aged men (usually between 45 and 65 years old) with at least one associated cardiovascular risk factor (e.g., smoking, mild-to-moderate hypertension or well-controlled diabetes mellitus). However, in our sample women made up approximately 50% of the patients with dyslipidemia, a major cardiovascular risk factor. Of the large primary prevention trials published to date, only the AFCAPS-TexCAPS6 and HPS7 studies included women, but the degree of similarity between these studies and our sample was nonetheless only about 45%.

Another difference was that our patients with alterations in their lipid profile were older, on average, than the participants in earlier trials. In primary prevention studies, mean age of the selected patients (with the exception of the AFCAPS-TexCAPS6 and HPS7 studies) was usually 70 years at most. Aging of the population, and improvements in quality of life in older and oldest old patients, has meant that the percentage of older persons with hypercholesterolemia tends to increase. Pharmaceutical companies are now actively engaged in primary and secondary prevention studies in older patients. An example of such research is the PROSPER (PROSpective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly Risk) study,11 begun in 1999, which selected only patients aged 70 to 82 years and followed them for 3.5 years.

We can therefore say that many of our patients with dyslipidemia would not have been included in any of the large primary prevention studies of hyperlipidemia. According to the results of our analyses, these studies would have excluded from 54% to 97% of our patients.

Another factor that should be considered in evaluations of external validity is adherence to treatment, with a greater degree of commitment and control, at least initially, in clinical trials. The rate of chronic noncompliance with treatment in patients with dyslipidemia is said to be between 50% and 60%.12,13

To these considerations must be added the fact that the large studies used here for comparison were carried out in populations different from the one in our setting, with different dietary habits and a higher incidence of ischemic heart disease than in our setting. Consequently, the applicability of earlier findings to our population, and the risk/benefit ratio of the introduction of statins, need to be weighed against other measures (such as public health or dietary interventions) that can be used for the primary prevention of hypercholesterolemia.14

Conclusions

The findings for our population sample suggest that the degree of external validity of large studies of primary prevention and hypercholesterolemia is low. Many of our patients (54%-97%) with dyslipidemia would not have been included in these large studies. We believe that in the primary prevention of coronary heart disease, the decision to use pharmacological treatment to reduce lipid levels should be based on individual factors that determine cardiovascular risk, rather than on cholesterol values alone.