Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) rates vary between 1% and 20% depending on the type of diagnosis guide used, the test used in the assessment, psychosocial factors, and professional in charge of the assessment.

Goalto describe and compare current clinical ADHD assessment processes in public health system in two cohorts and analyze variables related to final diagnosis.

DesignDescriptive, multicenter, longitudinal (retrospective-prospective).

Locationprimary care (PC) centers in Oviedo, Asturias (Spain).

Participantsa Spanish clinical ADHD symptomatic sample (n=134) from two cohorts (2004 and 2009).

Variablesclinical professional in charge of ADHD assessment (PC, mental health professional [MH], neuropediatrician [NP]), type of test used in the assessment, confirmation/disconfirmation of ADHD diagnosis, and final diagnosis.

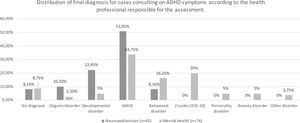

Resultsthe use of symptoms checklists and the assessments in charge of primary care (PC) and neuropediatrician (NP) professionals show an upward trend from 2004 to 2009. ADHD final diagnosis shows low inter-professional (NP-MH) reliability (kappa=0.39). Final diagnoses for the same symptoms are different depending on the professional (NP or MH).

Discussionsthe professional in charge of the assessment appears to be a relevant variable for the final diagnosis. ADHD diagnosis criteria seem not to be clear. This data suggests that ADHD diagnosis must be used with caution to ensure good quality clinical standards when assessing and treating ADHD symptoms. Assessments supported by symptoms checklists and performed by NP or PC could be contributing factors to an ADHD over-diagnosis tendency.

Las ratios del trastorno de déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH) varían entre el 1 y el 20%, dependiendo del tipo de guía diagnóstica utilizada, del test usado en la evaluación, de los factores psicosociales y del profesional a cargo de la evaluación.

ObjetivoDescribir el proceso actual de evaluación del trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH) en la práctica clínica en el sistema público de salud y analizar las variables relacionadas con el diagnóstico final.

DiseñoEstudio descriptivo y longitudinal (retrospectivo-prospectivo).

LocalizaciónCentros de atención primaria en Oviedo, Asturias (España).

ParticipantesSe analiza una muestra española de 134 casos clínicos en dos cohortes (2004 y 2009).

VariablesProfesional a cargo de la evaluación, test empleados en la evaluación y diagnóstico final.

ResultadosEl empleo de listas de síntomas y las evaluaciones a cargo de profesionales de atención primaria (AP) y de neuropediatría (NP) muestran una tendencia al alza entre 2004 y 2009. El diagnóstico final de TDAH muestra una baja fiabilidad interprofesional (kappa = 0,39).

ConclusionesEl profesional a cargo de la evaluación parece ser una variable relevante para establecer un diagnóstico final. Los criterios de diagnóstico de TDAH no parecen claros. Estos datos sugieren que el diagnóstico de TDAH debe usarse con precaución para garantizar una práctica clínica de calidad al evaluar y tratar los síntomas de TDAH. Las evaluaciones apoyadas por listas de síntomas y realizadas por NP o AP podrían ser factores que contribuyen a una tendencia de diagnóstico excesivo de TDAH.

Attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has been the focus of an extensive scientific debate concerning diagnosis, treatment, and type of health professional appropriate to manage these cases.1

Prevalence rates of ADHD vary from 1% to 20%,2 depending on the diagnostic guide used,3 the test used in the assessment,4 the consideration of the criteria of symptom interference,5 or the presence/absence of psychosocial factors influencing health status. These rates are higher when:

- –

the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) is used,3 instead of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD);

- –

the assessment is based exclusively on parents or teachers’ criteria instead of a clinical interview4;

- –

the assessment is not supported by tests. More information compiled during diagnosis decreases the prevalence of ADHD6,7;

- –

symptom interference criteria are not considered. Prevalence rates descend up to 77% when considering impairment criteria8;

- –

Diagnosis is emitted in Primary Care (PC) compared to when is emitted by a specialized service.9

The decision regarding which health professional should diagnose and treat children with ADHD symptoms seems to be a relevant aspect, as ADHD diagnosis must be based on a clinical interview. Previous literature defines two general tendencies regarding ADHD conceptualization.1 First, a neurobiological model which conceives ADHD as a syndrome pointing to one or several symptoms (hyperactivity, attention deficit, and impulsivity) with a neurobiological origin. This model suggests a stimulant-based pharmacological treatment to reduce the symptoms. In addition, this conceptualization points to the presence of other psychopathological symptoms that would indicate the existence of another comorbid disorder. This model is presented in DSM-510 in self-regulation theory11 and in the use of symptom checklists to diagnose ADHD. The second tendency presents a psychopathological model which conceives ADHD as a symptomatic manifestation of different types of mental functioning or temperamental factors. Understanding, treating, and trying to find an etiological explanation for the symptoms must be done as a unique case study, considering psychosocial and environmental factors as a main aspect in the assessment. Studies linked to this model warn about the importance of a good differential diagnosis,12 and point out that certain disruptive behaviors may be a normal reaction to very maladaptive environments.

The general aim of this paper is to describe and compare current clinical ADHD assessment processes in the public health system in two cohorts and to analyze the variables related to the final diagnosis. The specific goals of this paper are: (1) to describe clinical ADHD assessment tendencies among different health professionals: Primary Care (PC), Mental Health (MH) and Neuropediatricians (NP); (2) to describe clinical ADHD assessment tendencies among two cohorts (2004 and 2009); (3) to analyze whether the type of test used to identify ADHD and who is the professional in charge of the assessment are relevant components for the final diagnosis of ADHD.

MethodDesignDescriptive and observational study of two temporal cohorts (2004 and 2009). Cases were detected at the PC database for consultation on ADHD in 2004 and 2009, and then followed through their clinical history (CH) route.

ParticipantsThe sample included all cases meeting the inclusion criteria. The sample was taken from the digital database of cases attended at the Public Health Service in Oviedo (SESPA), Spain, based on the following criteria:

- 1.

Inclusion criteria:

- a.

Clinical register of consulting on ADHD symptoms in adult or pediatric PC assistance (registered as P21 code in the database) during 2004 and 2009.

- a.

- 2.

Exclusion criteria:

- a.

Consultations on ADHD symptoms made as an occasional contact for displaced patients (patients who do not usually reside in the sampled area).

- a.

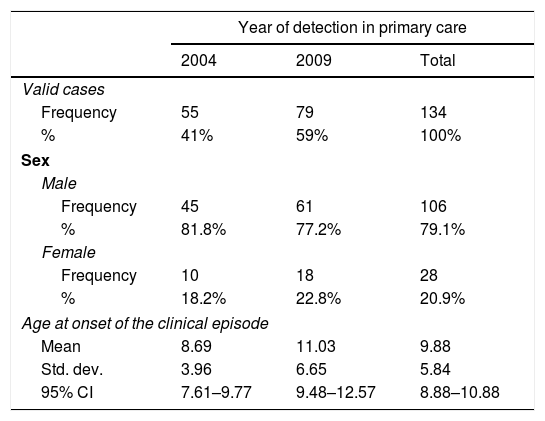

The final sample consisted of 134 clinical cases (55 cases from 2004, 79 cases from 2009; 106 males, 28 females). The sample is organized in two cohorts (number of cases during 2004 and 2009).

The main characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. The age-at-onset variability was greater in the 2009 cohort due to the statistically atypical detection of 4 cases of onset in adulthood.

Description of the total sample of the study.

| Year of detection in primary care | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2009 | Total | |

| Valid cases | |||

| Frequency | 55 | 79 | 134 |

| % | 41% | 59% | 100% |

| Sex | |||

| Male | |||

| Frequency | 45 | 61 | 106 |

| % | 81.8% | 77.2% | 79.1% |

| Female | |||

| Frequency | 10 | 18 | 28 |

| % | 18.2% | 22.8% | 20.9% |

| Age at onset of the clinical episode | |||

| Mean | 8.69 | 11.03 | 9.88 |

| Std. dev. | 3.96 | 6.65 | 5.84 |

| 95% CI | 7.61–9.77 | 9.48–12.57 | 8.88–10.88 |

The clinical route of patients following consultation on ADHD symptoms at PC services was investigated in a descriptive follow-up study (retrospective-prospective) of their Clinical History (CH). The Ethics Committee of the Central University Hospital of Asturias granted permission for the research as of May 2014. Data was collected during June and July 2014.

Variables and instrumentsFor every detected case we were granted access to the CH in order to collect the following variables:

- •

Socio-demographic variables: sex, age at onset of ADHD symptoms, date of consultation in PC. The population of this study was assisted by the Public Health Service of Oviedo (Spain) in 2004 and 2009.

- •

Organizational variables: patients sent for assessment from PC to other services (NP, MH or others). Patients consulting NP or MH services for ADHD symptoms (patients consulting these services could have been sent to NP or MH by clinical professionals different to PC).

- •

Assessment variables: public clinical professional responsible for the assessment (PC, MH, NP, or another clinical professional), tests employed to support the assessment (cognitive performance tests, symptom checklists, neuroimaging or other unspecified tests), tests used by each professional (PC, MH, NP, Private Psychopedagogical Services (PPS) or unspecified services). In cases assessed by MH or NP final diagnosis is also registered, as well as the clinical professional establishing the final diagnosis (MH or NP).

- -

Univariate study: descriptive measures of centralization and dispersion were used for quantitative variables. Descriptive analyses of frequency distributions were used for qualitative variables.

- -

Bivariate study: chi2 and Fisher's tests were used to describe changes among variables under study.

- -

Rates analyses: binomial test was used for rate comparison.

- -

Kappa concordance was used for ADHD diagnosis confirmation.

Descriptive analyses, chi2 and Fisher's tests were performed on SPSS 15.00. Rate analyses and kappa concordances were performed on EPIDAT 3.1.

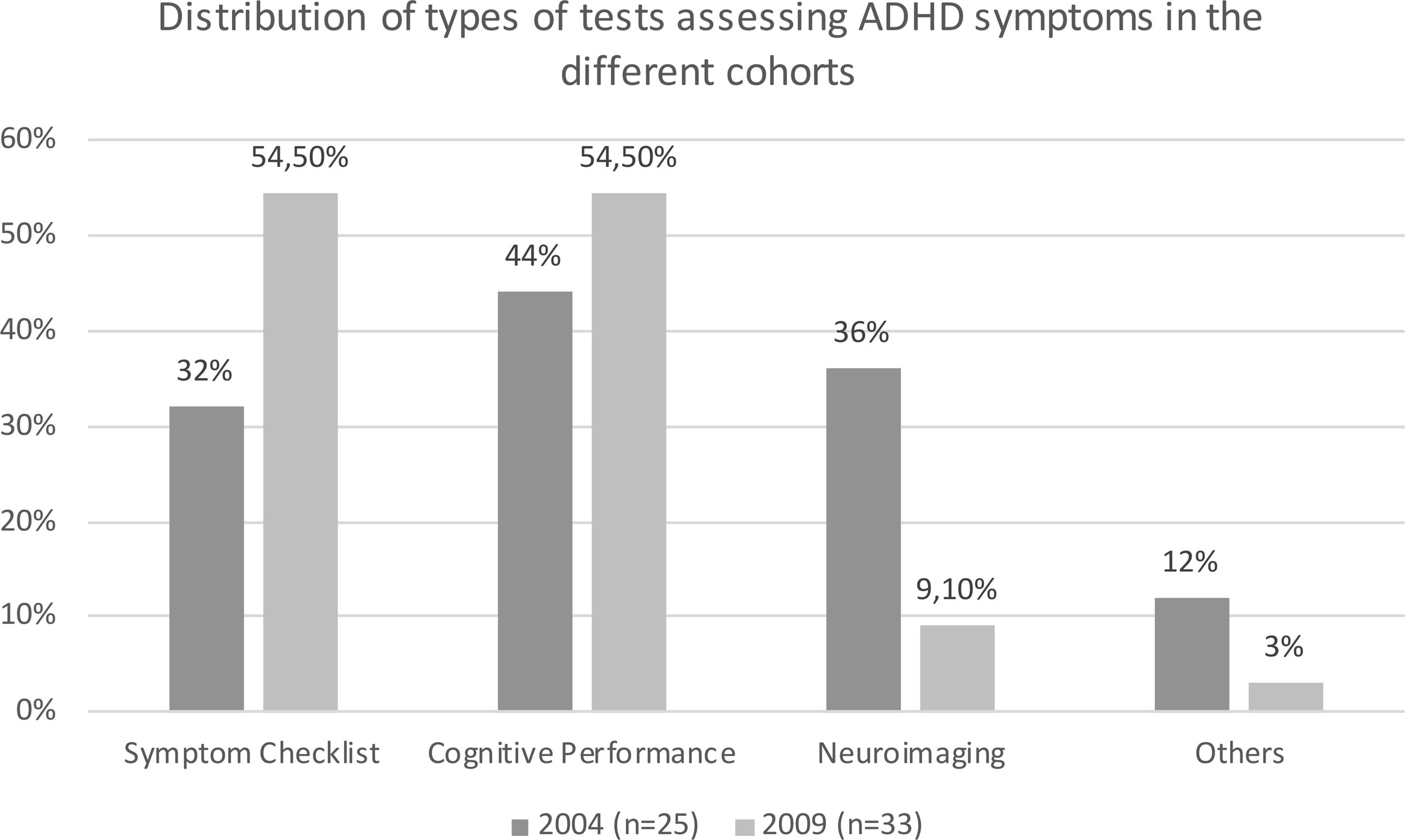

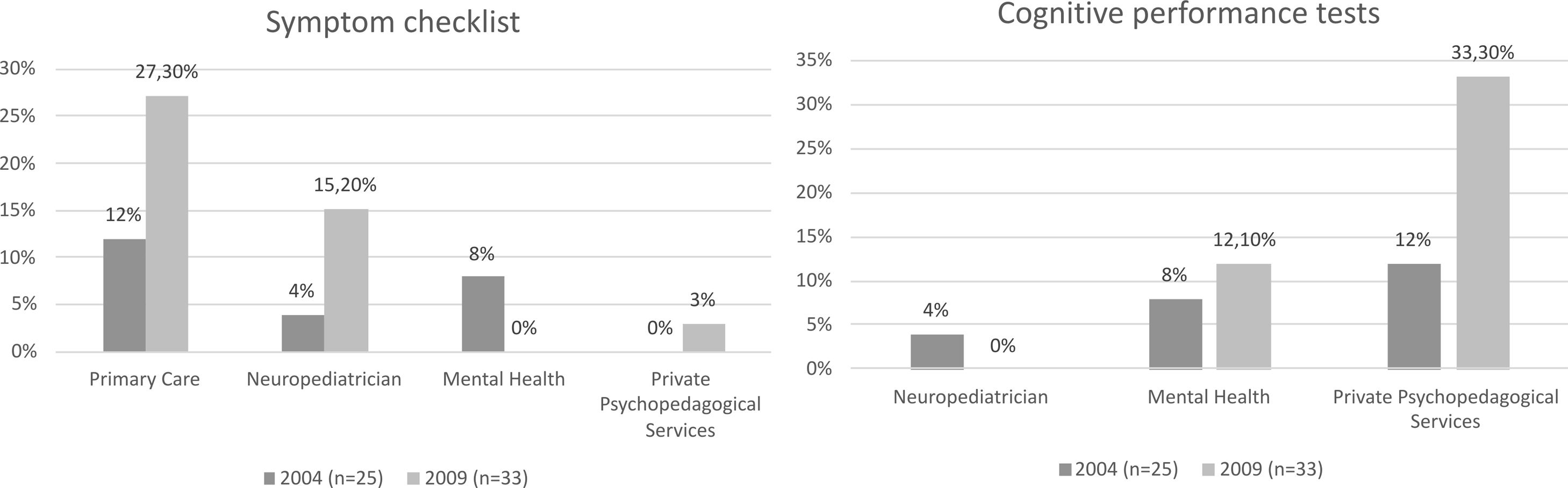

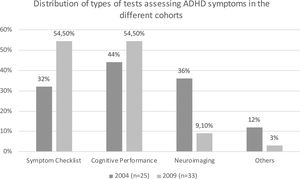

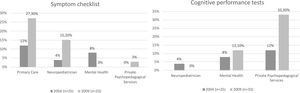

ResultsThe evaluation of a 43.3% (58 subjects) of the total sample (n=134) was supported by some test. From those 58 subjects, assessment was supported by a variety of tests, especially cognitive performance tests (50%, n=58) and symptom checklists (44.8%), followed by neuroimaging (2069%) and unspecified tests (6.70%). For the evaluation of those patients that was supported by any test (n=58 from the total sample) there is a different application of these among cohorts (Fig. 1) and health professional (Fig. 2). The use of symptom checklists (chi2, 1gl, p<0.001) and cognitive performance tests (chi2, 1gl, p<0.001) were related to higher ADHD diagnosis confirmation rates only when these tests were used by NP professionals, but not when they were used by MH professionals.

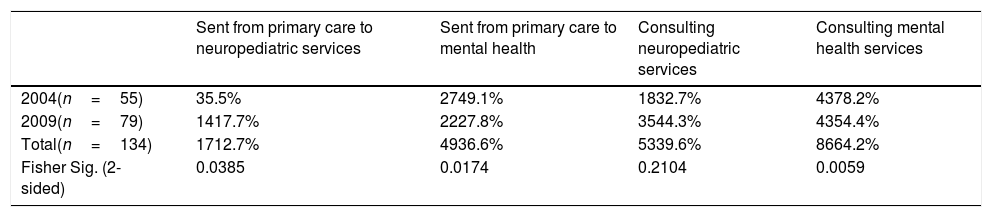

A 29.9% of de total sample (n=134) was not sent for assessment to other clinical services from PC, 36.6% has been sent for assessment to a MH professional, 12.7% has been sent to assessment to a NP professional, 17.9% has been sent for assessment to both professionals (MH and NP), and 3% has been sent for assessment to another clinical professional. As shown in Table 2, there is a significant increase in the 2009 cohort of cases sent to NP assessment services compared to 2004 (Fisher, 2-sided, p=0.039), and a significant decrease in 2009 of cases sent to MH (Fisher, 2-sided, p=0.017) or using MH assessment services (Fisher, 2-sided, p=0.01).

Tendencies in derivations and consultations in Neuropediatric or Mental Health Services among cohorts.

| Sent from primary care to neuropediatric services | Sent from primary care to mental health | Consulting neuropediatric services | Consulting mental health services | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004(n=55) | 35.5% | 2749.1% | 1832.7% | 4378.2% |

| 2009(n=79) | 1417.7% | 2227.8% | 3544.3% | 4354.4% |

| Total(n=134) | 1712.7% | 4936.6% | 5339.6% | 8664.2% |

| Fisher Sig. (2-sided) | 0.0385 | 0.0174 | 0.2104 | 0.0059 |

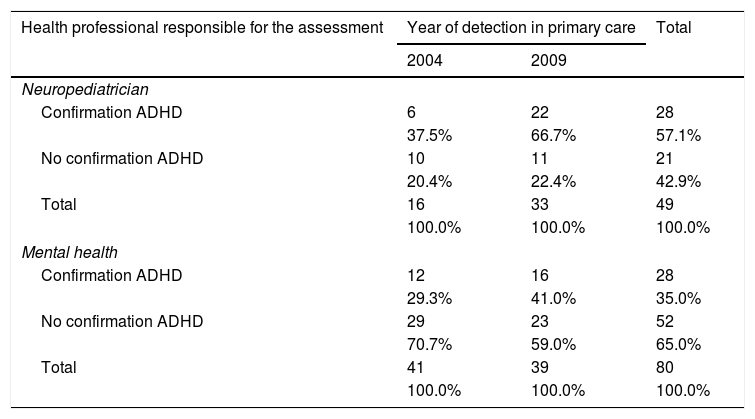

From 53 people using NP service for ADHD assessment, we have information on 49 subjects for the confirmation/disconfirmation of ADHD diagnosis. From 86 people using MH service for ADHD assessment, we have information for 80 subjects about the confirmation/disconfirmation of ADHD diagnosis. There are 34 subjects which was assessed by both clinical services, and there is information about confirmation/disconfirmation of ADHD diagnosis by both specialties for 29 of those cases. As for the confirmation of the diagnosis of ADHD in NP services, 57.1% of the total number of cases is confirmed, compared to 35% of the cases in MH (Table 3). Cases assessed by both services for ADHD symptoms (n=29) presented a low ADHD diagnostic confirmation concordance (kappa coef.=0.39). The rate of ADHD diagnostic confirmation is significantly higher (binomial, 1df, p=0.026) when public NP service is doing the assessment. The rate of ADHD diagnostic confirmation increased significantly in NP services (binomial, 1gl, p=0.049) between 2004 (33.3% of the sample assessed by NP in 2004) and 2009 (62.9% of the sample assessed by NP in 2009). The rate of ADHD confirmation by MH did not show a significant change in 2009 (37.2%) compared with 2004 (27.9%).

Confirmation of ADHD diagnosis according to the health professional responsible for the assessment.

| Health professional responsible for the assessment | Year of detection in primary care | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2009 | ||

| Neuropediatrician | |||

| Confirmation ADHD | 6 | 22 | 28 |

| 37.5% | 66.7% | 57.1% | |

| No confirmation ADHD | 10 | 11 | 21 |

| 20.4% | 22.4% | 42.9% | |

| Total | 16 | 33 | 49 |

| 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Mental health | |||

| Confirmation ADHD | 12 | 16 | 28 |

| 29.3% | 41.0% | 35.0% | |

| No confirmation ADHD | 29 | 23 | 52 |

| 70.7% | 59.0% | 65.0% | |

| Total | 41 | 39 | 80 |

| 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

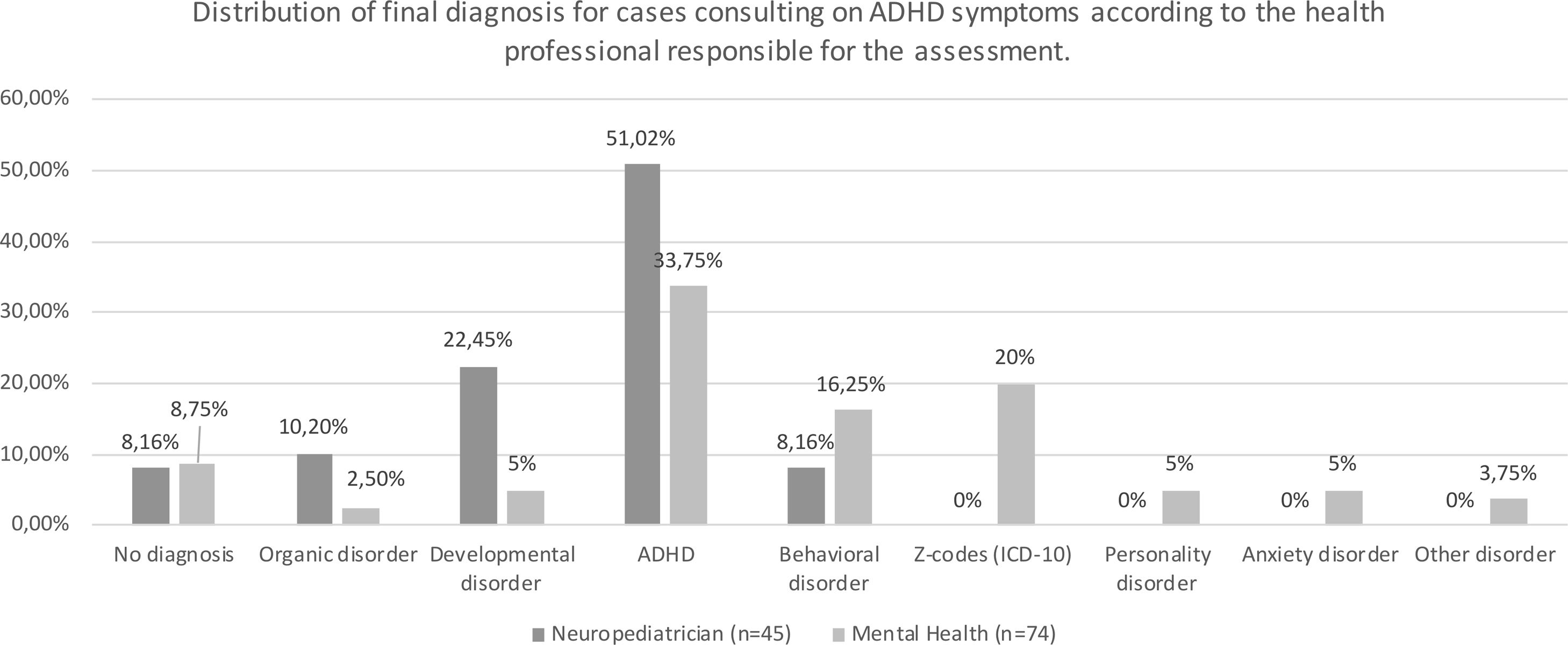

From 53 people using NP service for ADHD assessment, we have information for 45 subjects about final diagnosis. From 86 people using MH service for ADHD assessment, we have information for 74 subjects about final diagnosis. Diagnosis linked to ADHD symptoms differs depending on the assessing professional as shown in Fig. 3.

DiscussionMost cases analyzed did not have any assessment supporting test. Although tests are not necessary to make an ADHD diagnosis, some of them, such as cognitive performance tests or executive function tests, constitute a good complement for a better differential diagnosis. The lack of supporting tests is related to higher ADHD incidence rates as it has been shown in previous literature.6 Health professionals relying heavily on symptom checklists are PC and NP professionals. Symptom checklists have been related to higher ADHD rates as they are based on parents and teachers’ criteria. Furthermore, there are non-useful tests such as neuroimaging that are used, creating unnecessary costs. However, in the present study, ADHD rates were not related to the type of test employed in the assessment but to the professional using them instead. This data suggests that final diagnosis does not depend so much on the test employed, but on the professional implementing them.

Related to the health professional who diagnoses and treats ADHD symptoms, there are changes from 2004 to 2009: an upward trend of NP and PC professionals assessing ADHD cases, and a downward trend of MH professionals doing it. The increment of NP professionals in charge of ADHD assessment can be related to a current prevailing neurobiological model for ADHD.1 This prevailing model also affects the ADHD conception sustained by parents and educational systems, their needs, expectations and demands in the health system.

Previous literature9 points out that ADHD incidence rate is higher when the assessment is done by PC. However, results in the present study show a significant increase in ADHD rate when NP service is responsible for the assessment. As the data shows, NP is more likely to diagnose ADHD and developmental disorders for the same profile symptoms, whereas MH professionals distribute their main diagnosis among ADHD, Behavioral disorder or Z-Codes (presence of factors influencing health status and contact with health services as listed in ICD-10). The data could be indicating that different types of patients are sent to different services to be diagnosed (suspicious organic disorders tend to be sent to NP and other disorders may be sent to MH). Another hypothesis for this data is that different professionals sustain different ADHD conceptions when assessing the same symptoms. In relation to previous literature,1 a neurobiological conception tends to be sustained by NP professionals (considering mainly presence of symptoms), whereas a psychopathological conception could be sustained by MH professionals (considering psychosocial and environmental factors as a main aspect in the assessment and treatment process). Different conceptual models on the base of different diagnosis can be related with the low ADHD diagnostic kappa concordance results found in the present study.

This setting has important implications for PC professionals. Final diagnosis and treatment, when sending a child with ADHD symptoms for assessment, will vary significantly depending not only on the instruments and diagnosis criteria considered in the assessment,3,4,6–8 but also on the health professional the child is assigned to. It would be interesting to consider as a first step in ADHD assessment to start with a social assessment, which is usually run by mental health professionals. This way, social and environmental factors would be considered from the beginning of the process, avoiding in some cases an ADHD diagnosis and drug treatment in childhood.

Despite these results, limitations on this paper needs to be pointed out. Firstly, the sample used is a natural clinical context one without a unified ADHD diagnosis detection and assessment procedure. Therefore, the present study presents a good external validity but a weak internal validity. Secondly, data about symptoms could be collected, however impairment data was not sufficiently available in CH (most of the sample did not have registers about impairment caused by the symptoms). The appearance of statistical atypical cases of ADHD adulthood onset in 2009 is also remarkable. This could be pointing out to a possible upward trend of ADHD diagnosis in adulthood that needs to be considered.

Based on these results, we could predict an increase in ADHD diagnosis rates over the same population as long as ADHD symptoms are assessed, firstly supported by symptoms checklists without other cognitive or executive performance tests, and secondly, based on a neurobiological approach. This upward ADHD diagnosis trend is a noteworthy event considering the low inter-rater reliability found in this study for ADHD diagnosis. This context increases the probability of diagnosing and treating doubtful ADHD cases (false positive cases).

Based also on these results, we can point out that ADHD diagnosis and the prescription of psychotropic drugs seem not to be rooted on clear criteria. Gold clinical standards must be warranted in all cases, independently of the professional who diagnoses and treats the case. Further investigation needs to be developed for the establishment of clear and functional criteria to be used when diagnosing and treating ADHD.

Conflict of interestThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.