Introduction

An erroneous or incomplete pharmacotherapeutic history taken at the time of hospital admission can

lead to problems associated with medication not being detected and may lead to the inappropriate use or stopping of the drugs. If these errors continue when discharged from hospital, they can affect the efficacy of the treatment and the safety of the patient.1 Between 0.86% and 3.9% of patients seen in emergency departments are associated with iatrogenic reactions to drugs,2 and it is estimated that up to 11% of hospital admissions are due to their adverse effects.3 Some authors have pointed out that half of the medication errors may be generated in processes associated with changes in health care level.4-6 This indicates that the critical points of the system, when conciliation with the medication should be carried out are, when admitted to, and when discharged from hospital. Conciliation is understood as the formal process that consists of comparing the usual medication of the patient with the medication prescribed after a health care level transition or a transfer within the same level.

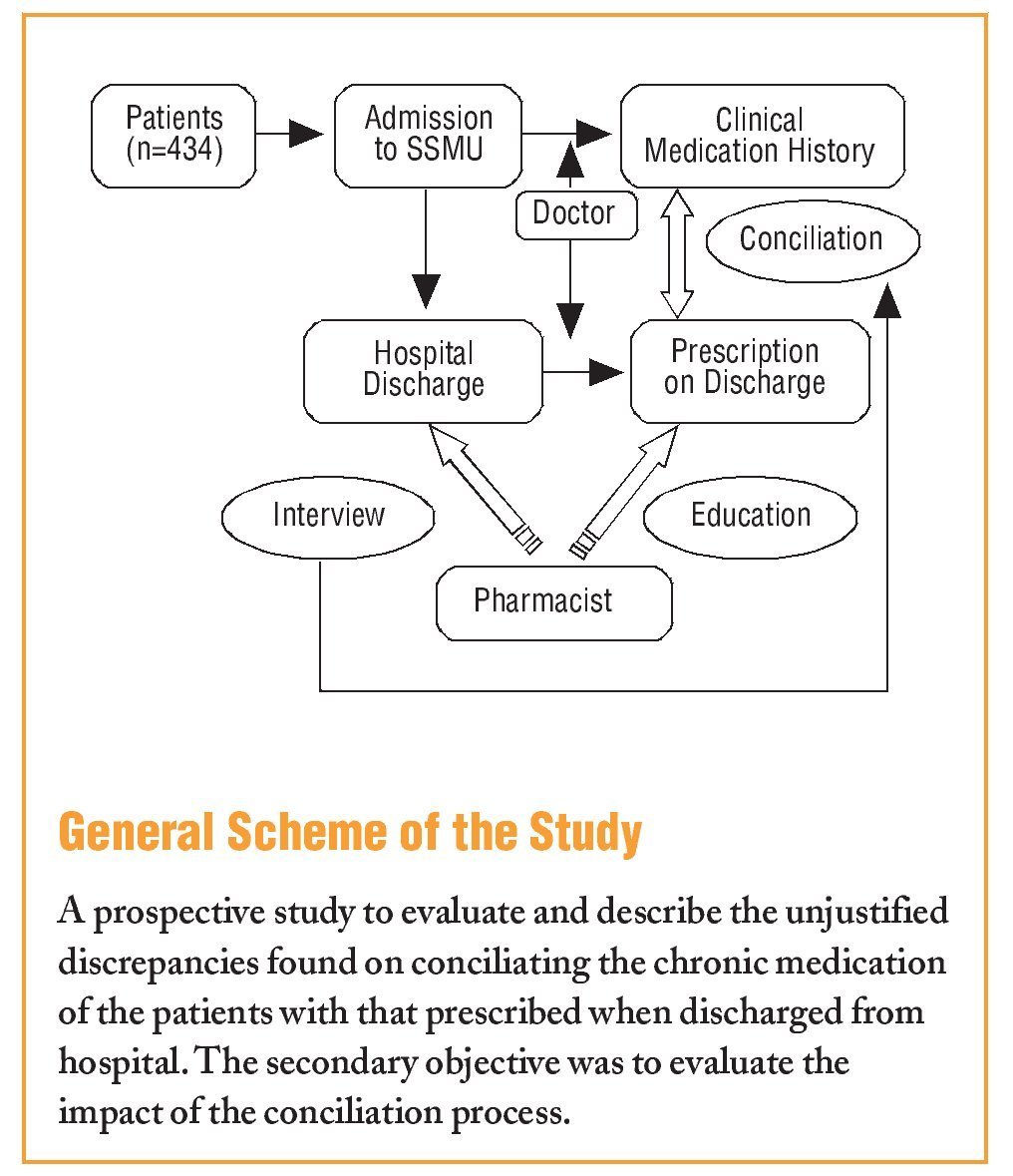

The objective of this study was, firstly, to evaluate and describe the unjustified discrepancies found on conciliating the usual medication of the patients with that prescribed at the time of hospital discharge. Secondly, the impact of the conciliation process was determined by assessing the potential seriousness of the discrepancies found.

Methods

The study was carried out on patients admitted to the Short Stay Medical Unit (SSMU) in Elda General Hospital, Spain. A descriptive-prospective study was performed from May to November, 2007. All patients who were discharged during working hours (8.00 to 15.00 h) from Monday to Friday were included. Patients were excluded if they were referred to other departments or to the hospitalisation at home unit.

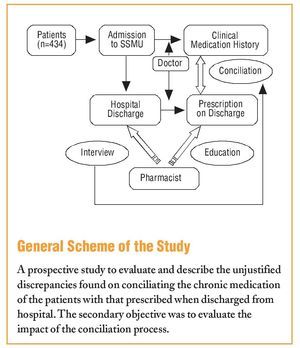

The conciliation process consists of comparing the list of medications the patient was taking at home with: a) the pharmacotherapeutic history obtained by the doctor at the time of admission to the unit, and b) the medication prescribed when discharged from hospital.

The pharmacist intervention took place at the time of discharge. The information on the usual treatment of the patients was always obtained by a clinical interview with them. In some cases, additional information was obtained from the reports prepared for primary care and from previous hospital prescriptions. Unjustified discrepancies or "conciliation errors" were defined as the disagreements or differences in the unintentionally prescribed treatment detected during the conciliation process.

These include the following types: omission or commission of medications; difference in the doses, route or frequency; incomplete prescription (dose, route, or interval not specified); duplicates, and interactions.

An error of omission was defined as the non-appearance of a drug in the pharmacotherapeutic history, but which the patients mentioned as being part of their usual medication. An error of commission was designated if the medication was recorded in their history and which, however, was not being used by the patient when admitted.

If unjustified discrepancies were found, they were clarified jointly with the doctor responsible.

The data were collected on a form specifically designed for this purpose, in which the following information was recorded: patient sociodemographic data, disease history, reason for admission, previous home medication and the pharmacotherapeutic history recorded by the doctor.

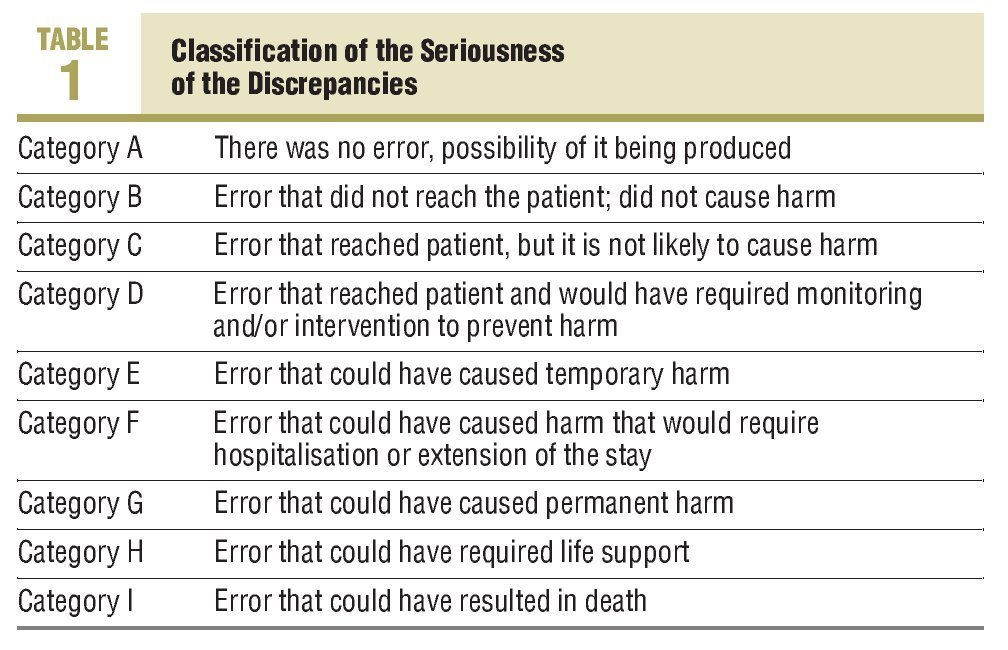

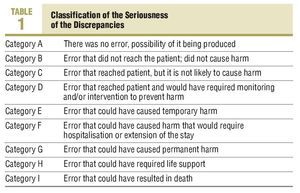

To assess the seriousness of the conciliation errors and to be able to evaluate the impact of the conciliation process, the classification by the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCCMERP)7 was used: a) with no potential harm (includes categories A-C); b) requires monitoring or intervention to prevent harm (category D); and c) potential harm (includes categories E-I) (Table 1). The pharmacist educated the patients at the time of being discharged from hospital, giving them a full report of their medication, prepared using the Infowin® computer program. This program provides graphical information of the medication packaging, and also explains the different ways of taking them, adverse effects and time-table planning.

A telephone number was given to resolve any problems associated with the pharmacotherapy of the patient. The patient was contacted by telephone 7 days after hospital discharge. The objectives were, on the one hand, to ensure that the medication was being taken as prescribed and, on the other hand, to detect any adverse effects to the treatment, and indicating the measures to follow.

Results

There was a total 843 hospital discharges from the SSMU, and 434 (51.5%) patients were interviewed. The rest of the patients were transferred to other departments, hospitalisation at home, or were discharged in the evening or during the weekend. There were 56% males and 44% females, with a mean age of 74±14.5 (15-101) years. The most frequent diagnoses were respiratory infection and heart failure. The mean stay in the Unit was 3±1.5 (1-8) days. The mean number of drugs at discharge was 8±3.31 (1-17), and the percentage of admissions due to problems related to medication was 4.6%. The mean number of patients seen per day by the pharmacist was 2.7.

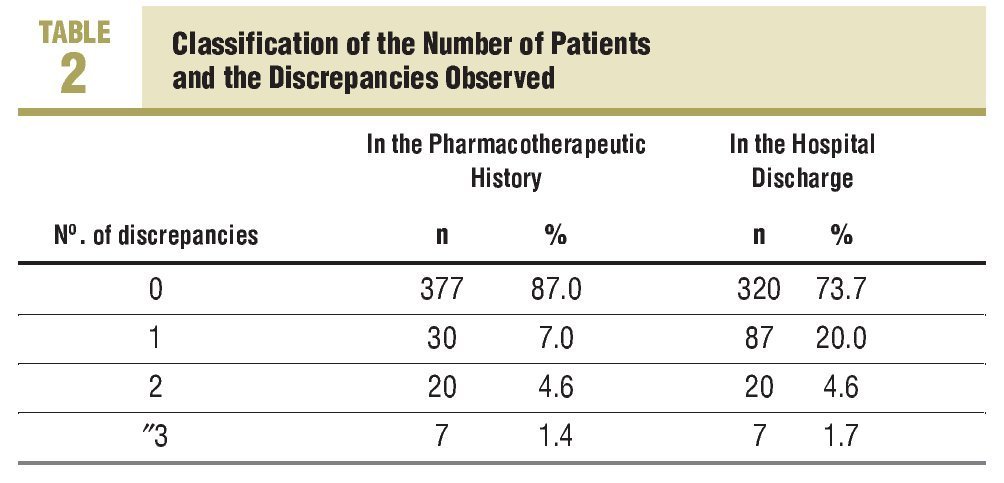

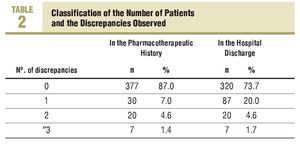

There were 249 conciliation errors detected from the total number of patients, which were 0.57 discrepancies per patient interviewed. There was a mean of 1.6 discrepancies found among the 35.2% (153) of patients who had conciliation errors. The classification of the number of discrepancies per patient in the conciliation with the history, as well as with the prescription at discharge is shown in Table 2. The conciliation with the pharmacotherapeutic history showed up 38.5% (96) of the errors, while 61.5% (153) were found on conciliating the usual medication taken with the hospital discharge prescription.

During the conciliation with the pharmacotherapeutic history, 12% of the patients had at least one error of omission, and 3% of them had a minimum of one error of commission. There was no information regarding the usual treatment on 11% (48) of the patients.

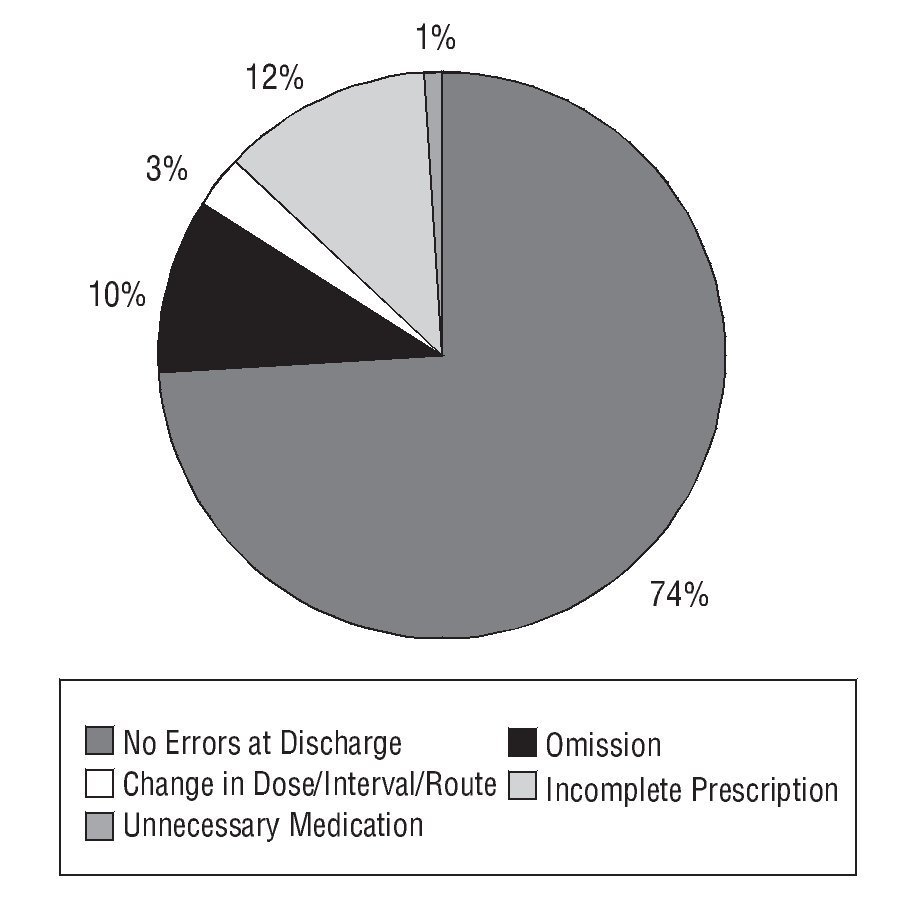

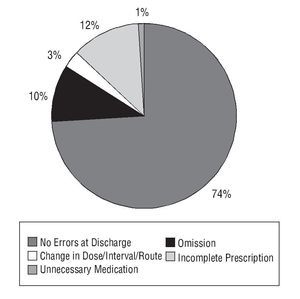

As regards the conciliation with the hospital discharge prescription, 43% of the discrepancies were due to drug omissions, 42% due to incomplete prescription (dose not indicated, 41%; interval not indicated, 1%), 10% due to unintentional changes in dose/interval/route, and 5% due to an unnecessary drug (Figure).

FIGURE 1 Type of errors at discharge and percentage of patients affected.

As regards the seriousness of the errors found in the hospital discharge prescription, the majority (67.3%) were included in category B. Temporary harm could have been caused by 27% of the discrepancies, therefore these were classified as category E, and another 2% as category F, that is to say, causing harm that could require hospitalisation. The rest (3%) were classified as category A.

Examples of the different discrepancies found and their categories can be seen in the Table shown in the electronic version of this article.

DiscussionThe SSMU was selected due to the characteristics of the patients seen there (advanced age, multiple medications, more than one illness, frequent admissions), which makes it ideal to fully benefit from intervention by the pharmacist, and in particular, from the conciliation of the medication. Also, on being a unit with a high rotation rate, it allowed a higher number of patients to be included. On the other hand, the previous relationship with the clinical team was very important, as well as their acceptance and collaboration.

The results of the study showed that 35% of the patients had some conciliation error, in agreement with the figures found in other studies. In this study, 61.5% were errors at hospital discharge, while 38.5% were detected in the pharmacotherapeutic history. These results differ from these reported by other authors, who have shown that 60% of errors are generated on admission and 40% at discharge.1,8,9 This higher percentage of errors at discharge observed in our study could be explained by the intervention only being at the time of hospital discharge, which would limit the early detection of discrepancies. The published data regarding errors found during the conciliation with the pharmacotherapeutic history are widely discordant. An explanation of this could be the methodological and conceptual differences of these studies. Some authors only looked at the omission errors on admission, while others looked at dose, frequency and commission errors. In this article, we have looked at omission and commission errors, but the differences in the dose or frequency were not taken into account, a fact that could explain why our figures were less than those obtained in other studies.

Tam et al10 showed that between 10% and 61% of patients had, at least one omission error. It should be pointed out that the majority of studies compared the pharmacotherapeutic history with the treatment at the time of admission, and in this study the discrepancies were established by comparing this with the information obtained at the time of discharge. It should also be highlighted that many studies speak of discrepancies including intentional ones (the clinical state of the patient justified these changes in treatment) and not unintentional ones. Thus, 13% of our patients had some error in the pharmacotherapeutic history. Similarly, at the time of discharge, the most common error type was that of omission (85%), while the rest (15%) were due to commission errors.

One important limitation was the absence of a validated source to identify the chronic medication. The pharmacist basically obtained this information from families and/or the patients, and in some cases, from the lists of chronic treatment by primary care.

Some authors have pointed out that the pharmacists recorded a mean of 5.6 medications/patient, compared to the 2.4 medications/patient obtained from doctors.11 A possible explanation could be that the doctor obtains the information immediately when the patient is admitted. On the other hand, the priority objective for the doctor is to clinically attend to the patient, therefore previous pharmacological treatment is relegated to a lower level. Also, for the patient, the fact that they are admitted may be a distressing time and, for this reason may not be able to give adequate information on their treatment.

For these reasons, the pharmacist should be routinely involved in the preparation of the pharmacotherapeutic history at the time of admission, particularly in risk groups (advanced age, multiple medications, drugs with a narrow therapeutic margin). Also, without intervention, almost 30% of the discrepancies could have caused temporary harm to the patient or hospitalisation. To avoid many of these errors, some routine habits in clinical practice should be changed. Among these are the omission of the drug dose at the time of discharge (although they seem obvious in principle) and writing of phrases such as "rest of the treatment as usual," since these situations generate possible errors and are unsafe, therefore they should be avoided. The aim of pharmacist intervention is to improve the pharmacotherapy received by the patient and, by conciliating the medication, to decrease the possibility of generating errors in this. Hospital admission and discharge are considered as critical points of action.

Advances are being made in this field, but the terms need to be homogenised to be able to compare results and to have better knowledge of the situation in each area.

As health professionals we should be aware and educate patients in the importance of having updated information on their medication. Increasing knowledge and understanding of their treatment should help to increase compliance and avoid medication errors.

What Is Known About the Subject

•There are unjustified discrepancies in the usual treatment of patients when patients move from one health care level to another.

What This Study Contributes

•The detection and quantification of discrepancies that are produced in changes of health care level can be intervened early, which ensures patient safety and improves the quality of their pharmacotherapy.

Spanish version available www.elsevier.es/244.932

A commentary follow this article (page 601)

Correspondence:

C. Hernández Prats.

Poeta Antonio Marín, 17, 7.º A. 03400 Villena. Alicante. España.

E-mail: hernandez_carpra@gva.es

Manuscript received February 19, 2008.

Manuscript accepted for publication May 28, 2008.