The HAPPY AUDIT study was aimed at demonstrating if a strategy based on multiple actions could reduce antibiotic prescriptions for respiratory tract infections (RTI) in primary care. This multifaceted strategy consisted of the discussion of the results of a first registration carried out in 2008, use of clinical guidelines on RTIs, information leaflets available to patients, and the provision of two rapid diagnostics tests and a workshop on how to perform and interpret these tests. The registration was repeated in 2009, and also in 2015 (HAPPY AUDIT 3), in which a total of 121 GPs out of 210 who participated in 2008 and 2009 agreed to participate again.1 A qualitative research was planned among the professionals who took part in the third audit-based study in order to find out the GP perception on the utilisation of antibiotics for RTIs and the usefulness of different strategies aimed at reducing unnecessary prescribing. The interviews took place from April to May of 2015.

A purposive sample of GPs from these areas was used to identify GPs who were likely to have differing views and perceptions of antibiotic prescribing. A target of ten GPs was estimated, or until saturation was indicated through data analysis. Sixteen GPs (two from each area) were sent an electronic participation information leaflet by the same investigator and signed by AM, LB and CL. In the end, we carried out eight interviews and since we realised that in the last interviews no new themes emerged, we considered that we had arrived at a saturation point so we did not select more professionals. An interview topic guide defined the main topics while allowing flexibility to search issues in more depth as they emerged from the interviews. Three broad subject areas were explored: antibiotic prescribing for RTIs in primary care, use of rapid tests, and perceptions about their participation in the HAPPY AUDIT study. The interviews were carried out always by the same investigator (AM). Interviews were recorded, anonymised and transcribed verbatim, which was performed by the same investigator as the interviews 24–48h after.

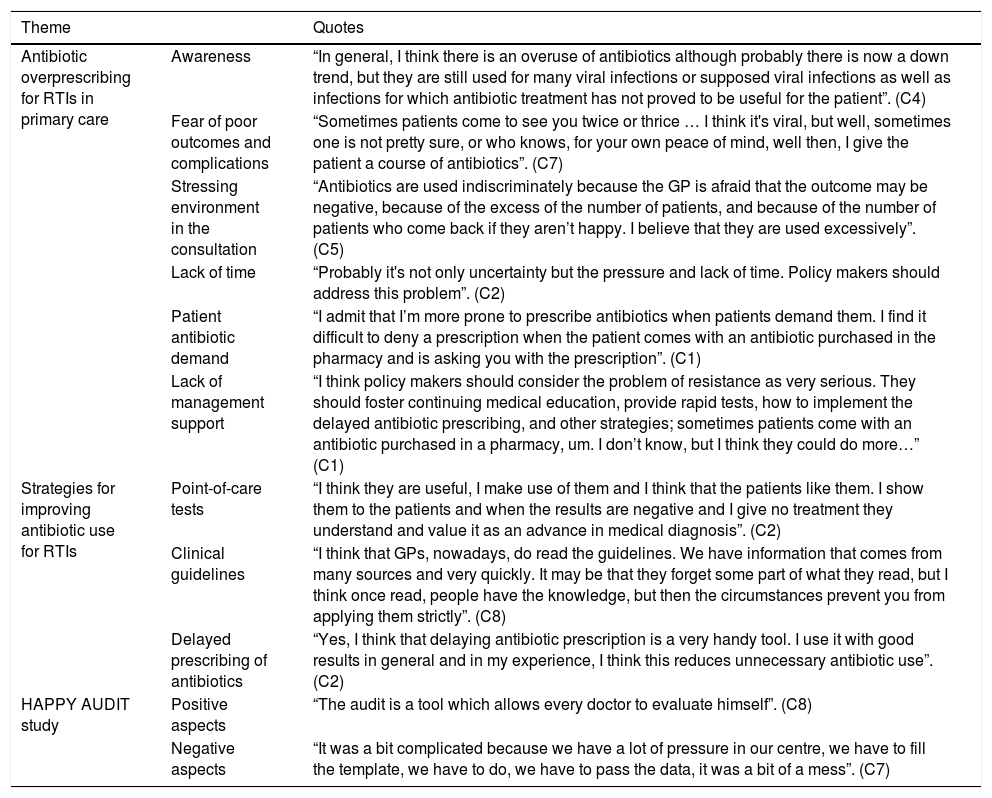

The mean age of clinicians was 54 years, with half participants of each gender. A clear perception of antibiotic overprescribing for RTIs was expressed. Different reasons for overprescribing emerged from the analysis: fear of poor outcomes or complications, lack of time in the consultation, low support from policy makers, antibiotic patient demand, and doctor workload (Table 1).

Quotations told by the family physicians interviewed.

| Theme | Quotes | |

|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic overprescribing for RTIs in primary care | Awareness | “In general, I think there is an overuse of antibiotics although probably there is now a down trend, but they are still used for many viral infections or supposed viral infections as well as infections for which antibiotic treatment has not proved to be useful for the patient”. (C4) |

| Fear of poor outcomes and complications | “Sometimes patients come to see you twice or thrice … I think it's viral, but well, sometimes one is not pretty sure, or who knows, for your own peace of mind, well then, I give the patient a course of antibiotics”. (C7) | |

| Stressing environment in the consultation | “Antibiotics are used indiscriminately because the GP is afraid that the outcome may be negative, because of the excess of the number of patients, and because of the number of patients who come back if they aren’t happy. I believe that they are used excessively”. (C5) | |

| Lack of time | “Probably it's not only uncertainty but the pressure and lack of time. Policy makers should address this problem”. (C2) | |

| Patient antibiotic demand | “I admit that I’m more prone to prescribe antibiotics when patients demand them. I find it difficult to deny a prescription when the patient comes with an antibiotic purchased in the pharmacy and is asking you with the prescription”. (C1) | |

| Lack of management support | “I think policy makers should consider the problem of resistance as very serious. They should foster continuing medical education, provide rapid tests, how to implement the delayed antibiotic prescribing, and other strategies; sometimes patients come with an antibiotic purchased in a pharmacy, um. I don’t know, but I think they could do more…” (C1) | |

| Strategies for improving antibiotic use for RTIs | Point-of-care tests | “I think they are useful, I make use of them and I think that the patients like them. I show them to the patients and when the results are negative and I give no treatment they understand and value it as an advance in medical diagnosis”. (C2) |

| Clinical guidelines | “I think that GPs, nowadays, do read the guidelines. We have information that comes from many sources and very quickly. It may be that they forget some part of what they read, but I think once read, people have the knowledge, but then the circumstances prevent you from applying them strictly”. (C8) | |

| Delayed prescribing of antibiotics | “Yes, I think that delaying antibiotic prescription is a very handy tool. I use it with good results in general and in my experience, I think this reduces unnecessary antibiotic use”. (C2) | |

| HAPPY AUDIT study | Positive aspects | “The audit is a tool which allows every doctor to evaluate himself”. (C8) |

| Negative aspects | “It was a bit complicated because we have a lot of pressure in our centre, we have to fill the template, we have to do, we have to pass the data, it was a bit of a mess”. (C7) |

In this first study aimed at evaluating the opinions of Spanish GPs on antibiotic prescribing for specifically RTIs it is documented that there is a perception of excessive prescription and that rapid tests, as well as the delayed antibiotic prescription, may be good tools to decrease it. Spanish GPs blame the administration for not taking the problem of antimicrobial resistance seriously enough. They particularly express concerns about the patient burden and the short time per patient in our surgeries. This is even more important considering that using point-of-care tests in the consultation or implementing the delayed antibiotic prescribing takes time as also mentioned in other qualitative research-based studies.2–5 The findings obtained in our paper offer a novel insight into GP's prescribing practice for RTIs in primary care in Spain. Strategies to make prescriptions of antibiotics more accurate with the aim of reducing antibiotic overprescribing should be encouraged. This should be accompanied with a greater involvement of the administration in order to have less stressful consultations, fewer number of patients and increase consequently the length of GPs’ consultations.

Ethics aspectsThe study has satisfied the ethical requirements of the CEIC Jordi Gol i Gurina (ref. number P14/132).

FundingThis study was funded by TRACE (Translational Research on Antimicrobial resistance and Community-acquired infections in Europe).

Conflict of interestAM and CL report receiving research grants from Abbott Diagnostics. JMM has received financial support for two studies from GSK and Gilead respectively. LB has nothing to declare.

We wish to thank Enriqueta Pujol-Ribera from IDIAP Jordi Gol i Gurina for her advice for conducting this qualitative research, Enrique Moragas, Aurelia Moreno and the different GPs who participated in this study.