Urinary tract infection (UTI) is one of the most common acute bacterial infections among adult females and accounts for about 15–20% of antibiotics prescribed.1 However, up to 60% of patients receiving an antibiotic for an UTI do not have a microbiologically confirmed UTI.2 While point-of-care tests have being actively promoted, these tests have often been introduced into routine care before rigorous studies. Some Scandinavian countries have used microscopy to detect bacteriuria for several decades, but to date no study has validated its use in current practice. This study was aimed at assessing its validity for the diagnosis of uncomplicated UTI in women, considering urine culture as the gold standard.

A diagnostic accuracy study was carried out in two primary health care centers from 2008 to 2016. Women aged 14 years or older with suspected uncomplicated UTI, defined as the presence of at least dysuria, urgency or frequency, were consecutively recruited. A clean-catch midstream urine specimen was collected from each patient and divided into three tubes: one for microscopic analysis, another one for dipstick analysis, and the remaining sample was sent to the Microbiology Department for assessment of pyuria and urine culture. The microscopic examination was carried out by phase-contrast microscope at a magnification of 400× of an unspun drop of urine obtained within the first 20min after being taken and was always carried out by the same investigator who was blind to all the variables collected. The physician performing the microscopic evaluation had undergone previous training in microscopic analysis. Samples which underwent microscopic evaluation at a later time were stored in the fridge until analysis. Samples kept longer than 24h were discarded. A positive urine culture was defined as more than 1000colony-forming units (CFU) of pure or predominant recognized uropathogen per milliliter, as recommended by IDSA.3 Significant bacteriuria was defined as the presence of >105CFU/mL according to Kass,4 and is still considered as the threshold for considering UTI in some countries. The validation parameters of the different diagnostic methods used were calculated.

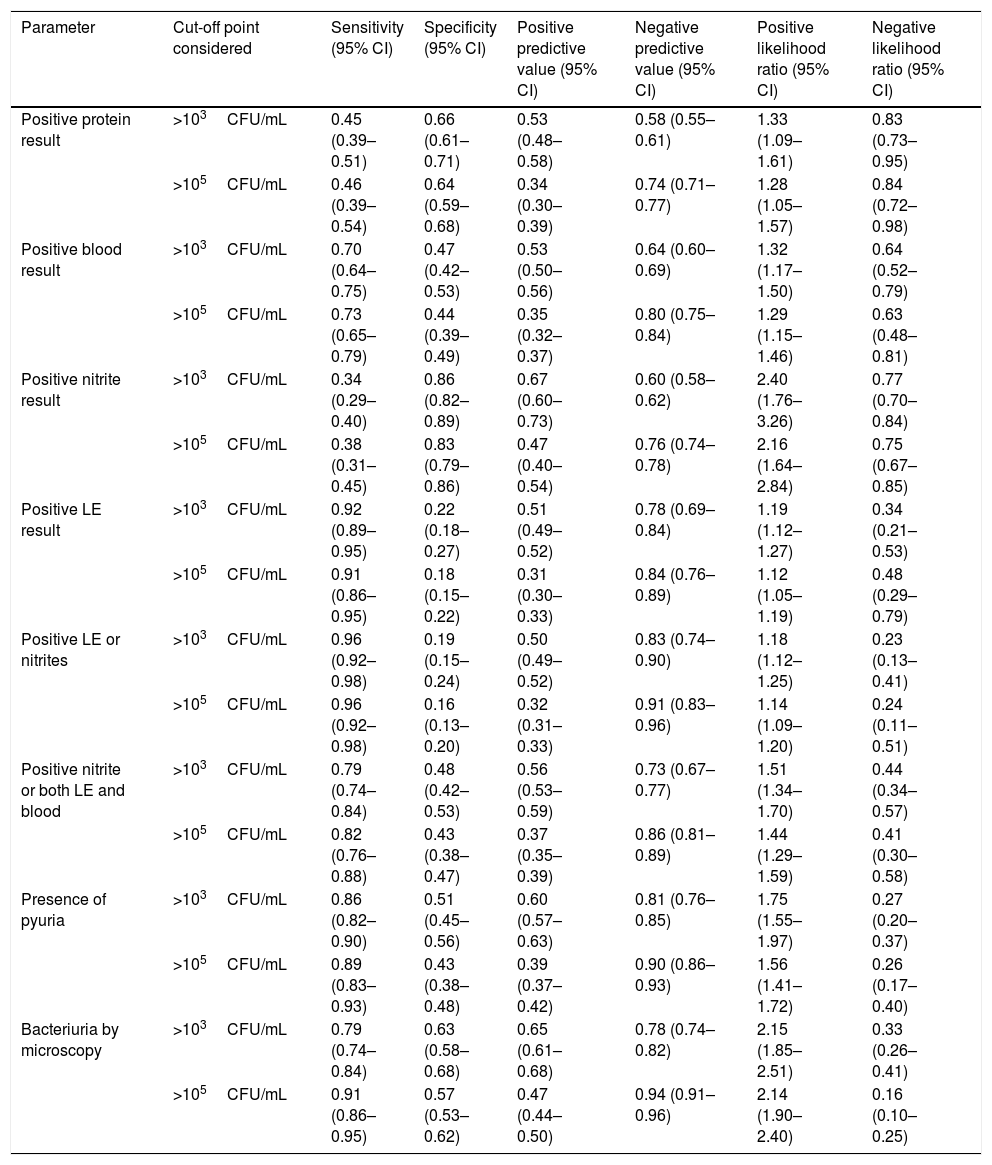

Of the 689 eligible urine samples collected, 631 were finally analyzed. Of these, 167 (26.5%) presented bacterial contamination and 292 (46.3%) presented UTI. Among the latter, 184 (67%) presented significant bacteriuria. The mean age of the patients included was 44.1±19.3 years. Microscopy presented a sensitivity of 0.79 and a specificity of 0.63. However, this point-of-care test performed better when a significant bacteriuria was considered (Table 1). Bacteriuria by microscopy was the best predictor of positive urine culture, achieving an AUC of 0.71 (95% CI, 0.67–0.75).

Validity of the diagnostic tools used for the diagnosis of UTI.

| Parameter | Cut-off point considered | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Positive predictive value (95% CI) | Negative predictive value (95% CI) | Positive likelihood ratio (95% CI) | Negative likelihood ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive protein result | >103CFU/mL | 0.45 (0.39–0.51) | 0.66 (0.61–0.71) | 0.53 (0.48–0.58) | 0.58 (0.55–0.61) | 1.33 (1.09–1.61) | 0.83 (0.73–0.95) |

| >105CFU/mL | 0.46 (0.39–0.54) | 0.64 (0.59–0.68) | 0.34 (0.30–0.39) | 0.74 (0.71–0.77) | 1.28 (1.05–1.57) | 0.84 (0.72–0.98) | |

| Positive blood result | >103CFU/mL | 0.70 (0.64–0.75) | 0.47 (0.42–0.53) | 0.53 (0.50–0.56) | 0.64 (0.60–0.69) | 1.32 (1.17–1.50) | 0.64 (0.52–0.79) |

| >105CFU/mL | 0.73 (0.65–0.79) | 0.44 (0.39–0.49) | 0.35 (0.32–0.37) | 0.80 (0.75–0.84) | 1.29 (1.15–1.46) | 0.63 (0.48–0.81) | |

| Positive nitrite result | >103CFU/mL | 0.34 (0.29–0.40) | 0.86 (0.82–0.89) | 0.67 (0.60–0.73) | 0.60 (0.58–0.62) | 2.40 (1.76–3.26) | 0.77 (0.70–0.84) |

| >105CFU/mL | 0.38 (0.31–0.45) | 0.83 (0.79–0.86) | 0.47 (0.40–0.54) | 0.76 (0.74–0.78) | 2.16 (1.64–2.84) | 0.75 (0.67–0.85) | |

| Positive LE result | >103CFU/mL | 0.92 (0.89–0.95) | 0.22 (0.18–0.27) | 0.51 (0.49–0.52) | 0.78 (0.69–0.84) | 1.19 (1.12–1.27) | 0.34 (0.21–0.53) |

| >105CFU/mL | 0.91 (0.86–0.95) | 0.18 (0.15–0.22) | 0.31 (0.30–0.33) | 0.84 (0.76–0.89) | 1.12 (1.05–1.19) | 0.48 (0.29–0.79) | |

| Positive LE or nitrites | >103CFU/mL | 0.96 (0.92–0.98) | 0.19 (0.15–0.24) | 0.50 (0.49–0.52) | 0.83 (0.74–0.90) | 1.18 (1.12–1.25) | 0.23 (0.13–0.41) |

| >105CFU/mL | 0.96 (0.92–0.98) | 0.16 (0.13–0.20) | 0.32 (0.31–0.33) | 0.91 (0.83–0.96) | 1.14 (1.09–1.20) | 0.24 (0.11–0.51) | |

| Positive nitrite or both LE and blood | >103CFU/mL | 0.79 (0.74–0.84) | 0.48 (0.42–0.53) | 0.56 (0.53–0.59) | 0.73 (0.67–0.77) | 1.51 (1.34–1.70) | 0.44 (0.34–0.57) |

| >105CFU/mL | 0.82 (0.76–0.88) | 0.43 (0.38–0.47) | 0.37 (0.35–0.39) | 0.86 (0.81–0.89) | 1.44 (1.29–1.59) | 0.41 (0.30–0.58) | |

| Presence of pyuria | >103CFU/mL | 0.86 (0.82–0.90) | 0.51 (0.45–0.56) | 0.60 (0.57–0.63) | 0.81 (0.76–0.85) | 1.75 (1.55–1.97) | 0.27 (0.20–0.37) |

| >105CFU/mL | 0.89 (0.83–0.93) | 0.43 (0.38–0.48) | 0.39 (0.37–0.42) | 0.90 (0.86–0.93) | 1.56 (1.41–1.72) | 0.26 (0.17–0.40) | |

| Bacteriuria by microscopy | >103CFU/mL | 0.79 (0.74–0.84) | 0.63 (0.58–0.68) | 0.65 (0.61–0.68) | 0.78 (0.74–0.82) | 2.15 (1.85–2.51) | 0.33 (0.26–0.41) |

| >105CFU/mL | 0.91 (0.86–0.95) | 0.57 (0.53–0.62) | 0.47 (0.44–0.50) | 0.94 (0.91–0.96) | 2.14 (1.90–2.40) | 0.16 (0.10–0.25) |

LE: leucocyte esterase; CI: confidence interval.

We compared the diagnostic performance of the detection of bacteriuria with microscopy with pyuria and urine dipsticks, with their performance as surrogate markers of UTI being poor. This study had some limitations: only few health care centers participated and only one physician evaluated the urine samples by microscopy. In a Danish study, in which urine specimens with a known quantity of bacteria were sent to doctors for microscopic examination, it was found that phase-contrast microscopy presented a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 83%. However, these results cannot be compared with our study as the urine samples were artificially produced.5

Although microscopic detection of bacteriuria is rapid, this is not sufficiently accurate as the number of false positives is high. Furthermore, its cost is substantial. The need for improved and efficient POCT overcoming these limitations are urgently needed for helping doctors to make more rational decisions when dealing with patients with uncomplicated UTI.6 The ideal POCT for the detection of bacteriuria in the outpatient setting should be rapid, inexpensive, accurate, that could predict benefit from antibiotic therapy.

FundingNo funding bodies have supported this study. The microscope was purchased by the main researcher and was partially reimbursed by the Catalan Society of Family Medicine. The courses on microscopic observation were paid by the researcher himself. The Catalan Society of Family Medicine had no role in the design and conduct of the study.

Conflict of interestsDr. Llor and Moragas both report receiving research grants from Abbott Diagnostics. No other disclosures were reported.