Introduction

Prescribing medications is unquestionably one of the most relevant aspects of medical practice. For primary care physicians, this is a particularly important activity, as it is generally the family physician who writes the most prescriptions.

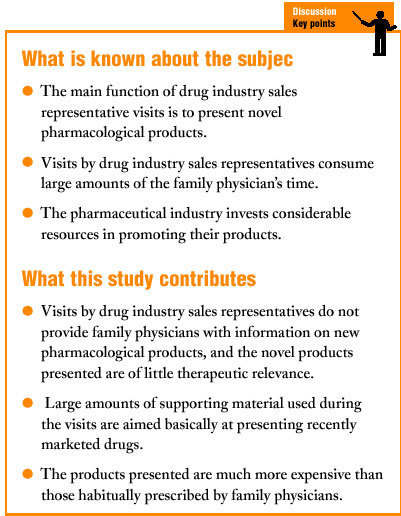

The pharmaceutical industry obviously tries to influence prescribing practices. Among the mechanisms used most commonly is advertising in medical journals, to the extent that almost 40% of the pages of a number of journals consist of advertising.1 Direct marketing by medical representatives, also known as drug industry sales representatives, is another frequently used mechanism. Although no information is available on spending by the pharmaceutical industry on advertising, staff costs and out-sourcing2 accounted for 42.5% of all operating costs in Spain in 1998.

The main job of these representatives is to sell new pharmacological products marketed by the pharmaceutical industry.3 Others have drawn attention to the large amount of time (and hence money and resources) primary care physicians spend listening to drug sales presentations. One editorial went so far as to estimate the cost of this time in monetary terms.4 Nevertheless, this editorial makes only passing mention of the time and expense primary care physicians devote in Spain to drug industry sales representatives.4 One talk given at a congress5 centered on medications publicized by direct advertising by the industry. However, neither of these sources4,5 investigated whether visits by sales representatives fulfilled their main function, i.e., to describe new pharmacological products to doctors.

The main objective of the present study was to determine whether visits by drug industry sales representatives served to describe novel pharmacological products to primary care physicians, and whether these products offered any actual therapeutic improvement. An additional aim was to investigate qualitative and quantitative indicators of the products described by drug representatives, and the manner in which they presented the products. A final aim was to investigate whether the products described by these representatives differed from those habitually prescribed by physicians at our center.

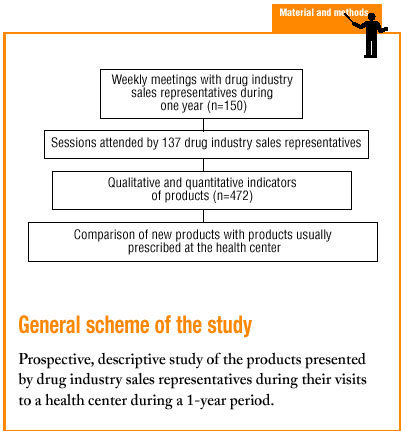

Material and methods

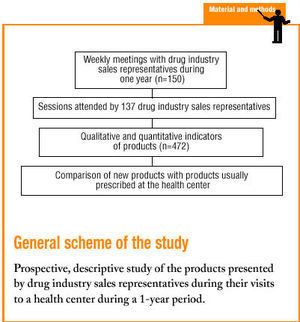

During a 13-month period from May 1998 to May 1999 we collected data from group meetings with drug industry sales representatives held at an urban health center serving a basic health area and accredited for training activities. At the time the study was begun, a total of 34 878 medical records were held at the center. All presentations were given in a single weekly session held on a weekday (Friday) from 2:00 PM to 3:00 PM. A maximum of 7 industry representatives made presentations during each session. All representatives had registered previously for a scheduled appointment, and all were drawn from a list of 150 representatives assigned to our basic health area, provided by the Professional Association of Drug Industry Sales Representatives.

All variables were recorded with a specially designed, standardized form. The unit of analysis was the representative, and information was recorded only for the first visit made by each representative at our center. This was because our aim was to investigate whether the initial visit by a new representative was used to present new drugs for primary care physicians. The following variables were recorded:

1. Given name and surnames of the representative, and name of the pharmaceutical firm represented.

2. Pharmaceutical products presented, anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) code6 and years on the market.

3. Intrinsic value of the product, as stated on the lists of prescription medications authorized by the Catalonian Health Service.

4. Evaluation of the novelty of the product in four categories: product presented previously, new active principle, new indication, or new route of administration. We also examined its therapeutic usefulness according to the classification of the Boletín de Información Terapéutica del Sistema Nacional de Salud:7 group A (substantial therapeutic improvement), group B (some therapeutic improvement) or group C (little or no therapeutic improvement).

5. Cost per unit and per defined daily dose (DDD) according to the ATC Classification Index of the World Heath Organization.6

6. Material provided by the representative: pamphlets, monographs, journals or journal reprints, books, small gifts (pens, calendars, notepads, adhesive notes, etc.) and product samples.

To compare the products described by the industry representative with products habitually prescribed by the physicians at the health center, we selected a random sample of the same number products from the list all products prescribed during the study period by physicians at the health center, and compared intrinsic value, cost per unit and cost per DDD.

Statistical analyses were done with SPSS software. Mean values were compared with Student's t test and analysis of variance, and proportions were compared with the *2 test. In all cases an alpha value of 0.05 was used.

Results

A total of 44 sessions with drug industry sales representatives were held at our center during the study period. Data were obtained for 308 presentations by 137 different representatives (91.3% of all industry representatives listed in the Professional Association of Drug Industry Sales Representatives directory for Barcelona), who represented 83 different pharmaceutical firms.

We studied a total of 472 pharmaceutical products. The representatives described a mean of 3.1 products during each visit (SD, 1.6; range, 1-7 products). Distribution according to ATC classification is shown in Table 1. 66 products (14%) had been on the market for less than 1 year, 138 (29.2%) had been available for 1 to 3 years, 105 (22.3%) for 3 to 5 years, and 163 (34.5%) for more than 5 years. Intrinsic value was high for 398 products (84.3%).

Table 2 shows that most products had been described in earlier presentations (93.4%). In fact, only 5.1% of the presentations were for new medications, and 1.5% were for new indications or new routes of administration. In other words, only 31 products (6.6%; 95% CI, 4.5-9.2) were novel. Their therapeutic usefulness was classified as group C (little or no therapeutic improvement in 22 medications (71%), group B (some therapeutic improvement) in 8 (25.8%), and group A (substantial therapeutic improvement) in 1 (3.2%). Four of the 31 novel medications (Table 2) were subsequently withdrawn because of severe side effects.

Mean cost per unit was 19.3 euros (SD 24.6 euros). Mean cost per DDD was 2.0 euros (SD 4.2 euros). Both cost per package and cost per DDD differed significantly (P<.006) when we stratified the products by date of appearance on the market: medications marketed more recently were more expensive both per package and per DDD (Table 3).

As shown in Table 4, supporting materials were used in the presentations of most of the products. Only 48 products (10.2%) were presented with no additional marketing aids.

Comparisons with habitual prescribing practices at our health center (Table 5) showed significant differences (P<.03) in the proportion of products with a high IV (the proportion was lower among products presented by drug industry representatives), cost per unit and cost per DDD (new products presented were more expensive).

Discussion

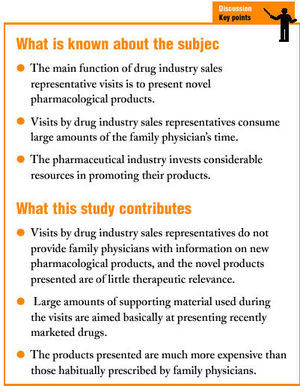

The results of the present study show that visits from drug industry sales representatives are made essentially for the purpose of promoting products that had already been presented previously. On a very few occasions, novel pharmaceutical products were presented--the main reason why physicians attend such talks.3 The few new products described do not often provide relevant therapeutic advances. Products presented shortly before, which are already on the market, are described with the aid of generous supporting materials but are backed by little scientific evidence, and are more expensive than the products habitually prescribed by physicians in our basic health area.

This study has certain limitations. Not all requests for an appointment from representatives were honored, and the proportion of representatives who missed their appointment was small. Some representatives, however, may have arrived for their presentation at a time or on a date other than the time allotted for them, and the behavior of some representatives may have been different when they spoke individually with physicians at the center.

To our knowledge no similar studies in Spain have been published, although the drug industry sales representative phenomenon has generated a number of editorials and commentaries.3,4,8-10 In fact, only one editorial4 discussed the costs (in terms of time and other expenses) incurred by drug representatives' visits at a health center, and gave some significant figures: 104 hours per physician per year, at a cost of 475 000 Spanish pesetas (2854.1 euros) per year. At our health center the total number of hours per year was lower, possibly because of the different organizational model for arranging and scheduling these visits. Biurrun et al5 studied quantitative and qualitative indicators of the products presented by industry representatives during a 3-month period, with results similar to ours. Specifically, the proportion of products with a high IV was 81.1%; the most frequent ATC groups were cardiovascular, anti-infectives, and alimentary tract and metabolism; and the most recently marketed drugs were also the most expensive.5 The cost per DDD was lower (215.4 pesetas, or 1.3 euros), given that their study was done in 1994.5

The substantial amounts of time primary care physicians invest in talking to industry representatives does not seem reasonable, given that during the study period they obtained information on only 31 novel products, most of which are of little relevance. Most of the novel medications were «me-too» drugs, and 4 new products were later withdrawn because of severe side effects. Some of the time might be better spent reading current publications that provide objective information for free, such as the Boletín de Información Terapéutica del Sistema Nacional de Salud (Bulletin of Therapeutic Information of the National Health System, prepared by the Spanish Ministry of Health).7

A further notable finding is that the medications presented by the pharmaceutical industry are much more expensive than those prescribed habitually. Overall, the cost per DDD (Table 5) was nearly 3-fold as high. These new drugs usually provide no additional benefits in comparison to cheaper drugs already on the market. In this connection, current Spanish legislation facilitates marketing practices by the pharmaceutical industry, a phenomenon that may contribute to the increasing costs of pharmaceutical products provided through the national health system.

It would be unrealistic to assume that repeated presentations with abundant supporting material are not accompanied by increased prescribing of these products. The enormous investments2 in advertising by the pharmaceutical industry aim to convince physicians to prescribe their products9 and thus to increase profits. This legitimate goal is clearly being achieved, as shown by the fact that despite their huge investments in advertising, pharmaceutical firms are most profitable in countries such as the USA.11 Similarly, it would be ingenuous to assume that the gifts offered to physicians (although of little monetary value), sponsorship of training activities, and free meals represent acts of altruism by industry representatives.9 The clearest proof of this is that the pharmaceutical industry forbids its own employees from receiving gifts from suppliers or clients.12 It has been shown that industry sponsorship of activities such as congress organization is accompanied by changes in physicians' prescribing practices.13 Even accepting small gifts, which doctors believe will not modify their prescribing practices, is accompanied by changes in clinical judgment, and therefore creates a conflict of interest.14

In light of these developments, we should not be surprised that the Spanish Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs as well as autonomous regional health administrations have attempted to regulate drug industry sales representatives' visits through guidelines emanating from the central government (Reales Decretos) and internal circulars. The Barcelona College of Physicians3 recently took a stand regarding the relationships between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry, although the guidelines this organ developed are less stringent than those of the American College of Physicians (ACP).13 In general, there is a consensus, shared by the national health administration and professional associations, that industry representatives' visits should be regulated, scheduled in advance, and limited in duration to a reasonable time.

The conclusion to be drawn from the present study is that visits from drug industry representatives do not provide physicians with relevant information regarding new drugs. It is therefore difficult to justify the large investments in time and money devoted to sessions with drug sales representatives. As other authors have appropriately observed,4,8,9 the model of industry relationships needs to be changed. Physicians should cease to be passive receptors of an enormous flow of information, most of little relevance, and adopt a role informed by users' needs and efficient pharmacological alternatives. These considerations have led to the proposal to move from an individual model toward a group model based on scientific information and training needs.8