Introduction

The stomach is the second most frequent site of cancer, accounting for 9.9% of all cases of cancer worldwide. This figure rises to 11.9% in men and decreases to 7.6% in women, among whom it is the fourth most frequent location after breast, colorectal and cervical cancer.1

The incidence of gastric cancer differs in developing countries, where the annual rate of new cases in men approaches that of lung cancer, and in developed countries, where there are more cases of prostate and colorectal cancer than of gastric cancer.2 In women the differences between developing and developed countries are smaller, but nonetheless evident. In fact, 38% of all cases of gastric cancer occur in The People´s Republic of China, where as occurs in other parts of Southeast Asia it is the most frequent type in both sexes. Gastric cancer is also the most frequent type (with rates higher than those for lung cancer) in tropical areas of South America. Within Europe the highest rates are reported for Eastern countries.1 The mortality rate/incidence ratio in men ranges from 0.40 in Japan to 0.89 in Central Asian countries, as compared to 0.86 in Europe. In women these figures range from 0.44 in Japan to 0.92 in temperate areas of South America, as compared to 0.83 in Europe.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) database indicates large variations for sexes and countries in age-adjusted mortality rates.3 During the period from 1995 to 1998, mortality rates surpassed 25 per 100,000 in men and 10 per 100,000 in women in the European countries of Belarus, Estonia, Russia, Latvia, Lithuania and the Ukraine. Age-adjusted rates in Spain for 1995 --the last year for which data are available-- were 12.2 per 105 in men and 5.5 per 105 in women, i.e., higher than in Denmark, France, Finland, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom.3 In the neighboring country of Portugal, these rates are almost twice as high as in Spain but now show a tendency to decrease, as in the rest of the world.4

There are several possible explanations for this trend. First, freezing and refrigeration technology has reduced the consumption of salted and smoked foods, preserved with techniques that have been associated in ecological studies with a high incidence of gastric cancer.5 In addition, current farming systems and improvements in transportation have increased the consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables throughout the year, another trend associated with a reduced risk of gastric cancer.6

Some authors have recently speculated that green tea might be associated with a lower risk of gastric cancer. However, although there is a consensus regarding the protective effect of a diet rich in fruits, vegetables and whole grain cereals, and regarding the increased risk associated with a diet rich in salt and salted or smoked foods, and possibly with the habitual consumption of barbecued meat and fish,6 the protective effect of green tea has yet to be widely accepted.7 Alcohol consumption is another likely risk factor for cancer located specifically in the gastric cardia.8

The relationship between gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori infection is also under investigation.9 Current studies are attempting to clarify whether antibiotic treatment aimed at eradicating the infection has a protective effect on the appearance or malignant evolution of gastric adenocarcinoma, or whether such treatment acts, as some have suggested, as a risk factor for gastric cancer in light of the fact that some strains of H. pylori (cagA+) appear to protect against the appearance of adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia.10 Intervention-based studies of the effects of treatment of H. pylori infection in patients in whom evolution of gastric cancer differ11 will help to clarify this relationship.

A genetic susceptibility to the appearance of gastric cancer was found in studies of isolated ethnic groups12 and patients´ relatives13, after possible confounding factors such as diet were taken into consideration. Finally, although the end of the 1980s saw reports of a relationship between ethylene oxide exposure and increased mortality from gastric cancer,15,16 more recent studies that measured mortality17 and incidence18 in cohorts with occupational exposure failed to confirm this association.

The aim of the present study was to describe the trends in mortality due to gastric cancer in Andalusia (southern Spain) during the final quarter of the twentieth century, and to provide information on the current geographic distribution of the disease in the primary care health districts that currently comprise this region.

Material and methods

Deaths from gastric cancer --code 151 in CIE 8-9 and code C16 in CIE 10-- were recorded from national (INE, Instituto Nacional de Estadística) and regional (IEA, Instituto de Estadística de Andalucía) statistical databases for the periods 1971-1991 and 1992-1999. Data for 1999 were considered provisional at the time of the this study. The inclusion criterion was residence in Andalusia, and the populations used in our analyses were based on estimates provided by the IEA. To describe temporal trends we calculated crude and age-adjusted (direct method, using the European population as the reference population) mortality rates, truncated rates for 35 and 64 years of age, and potential years of life lost between 1 and 70 years (PYLL).19 To calculate approximate figures for the risk of dying from gastric cancer in the absence of other causes we calculated cumulative rates for the ages 0 to 74 years20 as a percentage. To quantify changes in trends during the period from 1975 to 1999 we developed linear regression models with year of death as the independent variable and adjusted mortality rate as the dependent variable, and estimated regression coefficients for men and women. The SPSS (v. 8.0) was used for all calculations, and a 5% level of significance was used for tests of the independence of variables and for intercept and slope values other than zero. Normal distribution of the data was checked in all cases. Age-adjusted mortality rates per primary health care district during the period from 1995 to 1999, grouped in quintiles, were used to illustrate the geographic distribution of mortality from gastric cancer. Maps were created with the MapMaker program.

Results

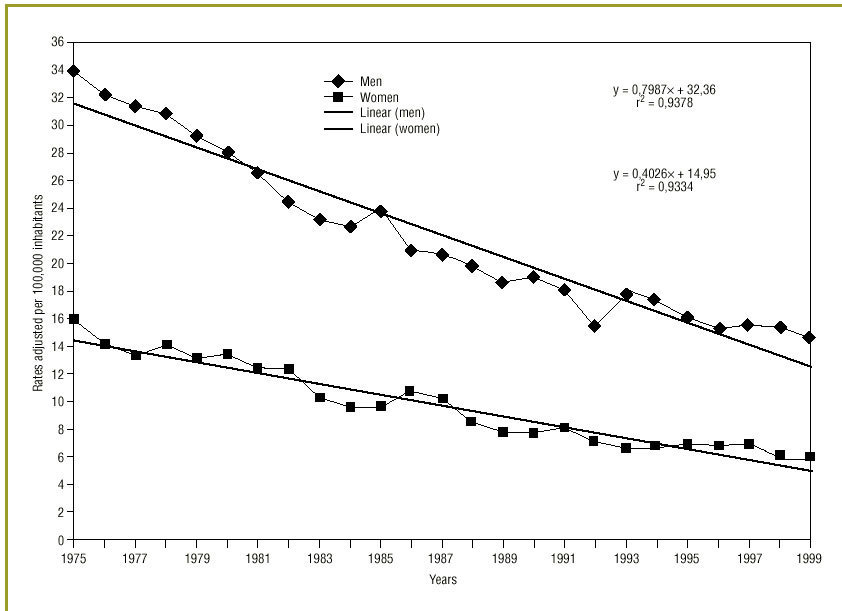

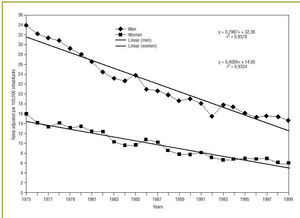

The mortality rate for gastric cancer in Andalusia decreased markedly between 1975 and 1999 (tables 1 and 2). Crude rates decreased to half the initial value in women and to two-thirds this value in men. Age-adjusted rates showed even larger changes, decreasing from 15.9 to 5.8 deaths per 100,000 in women and from 33.9 to 14.5 per 100,000 in men. The overall decrease was 63.5% in women and 57.2% in men. The male:female ratio remained higher than 2 in almost all years of study. Indicators of premature death --truncated rates and PYLL-- also fell in both sexes, and cumulative rates decreased from 1.08% to 0.39% in women, and from 2.48% to 1.07% in men. Figure 1 shows age-adjusted rates, regression equations and trends for both sexes according to the linear model, which best fit the changes in rates. These expressions can be used to estimate theoretical mortality rates.

Fig 1:Evolution of mortality rates for gastric cancer in Andalusia from 1975 to 1999.

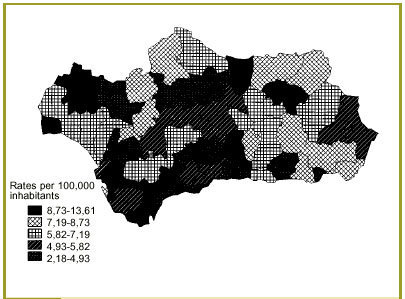

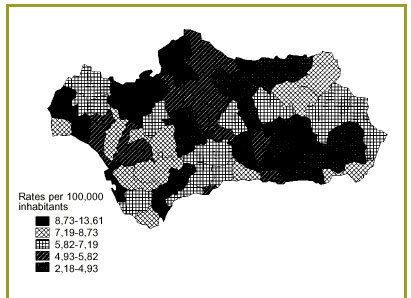

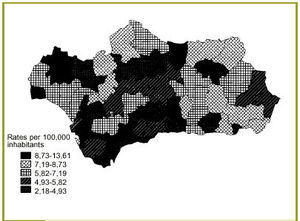

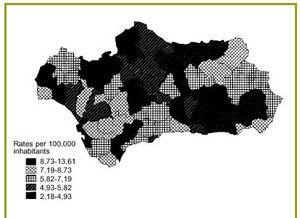

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the current geographic distribution of mortality from gastric cancer in all health care districts. In some districts in the provinces of Granada (Guadix), Seville, Huelva and Córdoba (Sierras Norte), mortality from gastric cancer in men was threefold as high as in those districts with the lowest rates. These local contrasts were even more striking for women.

Fig 2:Mortality rates for gastric cancer in women in Andalusia from 1975 to 1999.

Fig 3:Mortality rates for gastric cancer in men in Andalusia from 1975 to 1999.

Discussion

Our results document a notable decrease in mortality from gastric cancer in Andalusia, although the stomach remains the third most frequent site of cancer in men and the fourth most frequent site in women21. This trend is consistent with observations for the general population in Spain, where mortality rates peaked in the mid-1960s but have declined steadily since then3 to their current values. The reasons for this decrease, also reported in other European countries, are associated with a decrease in the incidence, and with more recent increases in survival. For decades, survival among patients with gastric cancer was so low --less than 10% after 5 years-- that the trend in mortality was assumed to accurately reflect the decreased incidence22 recorded in cancer registries in Spain and in other western countries. Recently published estimates23 of survival are slightly higher and have undoubtedly contributed to these decreases in mortality: European 5-year survival rates are 19.3% for men and 23.6% for women overall, and range from 8.4% and 10.1% respectively in Poland to 24.3% for Spanish men and 3.1% for Icelandic women. The trend found in Andalusia is therefore not unexpected.

With regard to the current geographic distribution of mortality, the large local differences between primary health care districts call into question the reliability of the information and the stability, for small areas, of mortality indexes that measure infrequent events. However, concordance studies of the causes of death which compared death certificates with clinical information for deceased patients have found official death statistics to be highly reliable both in Spain24 and in other countries25 where levels of development, reporting regulations and epidemiological coding practices are similar. Discrepancies in oncological statistics were found mainly for uterine cancers and mesotheliomas26, and overall discrepancies in mortality figures for cancer decreased by 35% between the late 1970s and 1980s. To ensure stability of the measurements, mean rates were calculated for the 5-year period from 1995 to 1999; when the window of time was enlarged, mortality rates stabilized even for areas with a low population, as are the primary health care districts compared in this study.

Attempts to compare areas of high and low mortality have led to the development of sophisticated statistical techniques28 which are useful in searching for patterns in geographical distribution, but which undoubtedly distract attention from the actual data.29 This was the reason which led us to present our findings as age-adjusted mortality rates. In overall terms, the incidence30 and mortality rates in Andalusia are too low to warrant the use of early detection programs such as those currently in use in Japan, which involve double-contrast barium x-rays followed by gastroscopic examination for all inhabitants older than 40 years. This approach has indeed succeeded in detecting gastric cancer in its early stages, and has reduced mortality and incidence rates.1 However, in Andalusia a more reasonable approach might be to develop preventive measures for those areas were mortality is high. Before such measures are attempted, previous studies will be needed to analyze morbidity, dietary patterns, genetic susceptibility and the prevalence of H. pylori infection, and statistical analyses of these data will need to take into account possible confounding factors such as occupational exposure and socioeconomic level..

Correspondence: Miguel Ruiz Ramos. Registro de Mortandad, Avda. Blas Infante 6, Edificio Urbis 8.ª planta, 41009 Sevilla, Spain. E-mail: mruiz@junta-andalucia.es.Manuscript accepted 18th July 2001.