To describe the practices and knowledge of Nursing Technicians and Community Health Agents of Primary Health Care for the transgender population.

DesignDescriptive research with a qualitative approach.

SiteThe study was developed in a digital environment.

Participants18 Community Health Agents and 12 Nursing Technicians who worked in Primary Health Care Units from several Brazilian states.

MethodSampling technique by chain indication or networks (snowball), data production by Google Forms form. The theoretical saturation technique was used to close the interviews. Categorical thematic content analysis with IRAMUTEQ software support.

ResultsProfessionals’ lack of knowledge about policies and terms was evidenced; there were conceptual confusions, inadequate associations, and a restricted approach to the prevention of sexually transmitted infections.

ConclusionsThe lack of training reflects a cisnormative and binary approach, compromising the assistance to the transgender population. Disrespect for the social name persists, highlighting the need for permanent education for health professionals, aiming at an inclusive and respectful care practice.

Describir las prácticas y los conocimientos de los técnicos de enfermería y agentes comunitarios de salud de atención primaria sobre la población transexual.

DiseñoInvestigación descriptiva con enfoque cualitativo.

EmplazamientoEl estudio se desarrolló en un entorno digital.

Participantes18 agentes comunitarios de salud y 12 técnicos de enfermería que trabajaban en unidades de atención primaria de salud de varios estados brasileños.

MétodoTécnica de muestreo por indicación en cadena o redes (bola de nieve) y producción de datos mediante formulario Google Forms. Para el cierre de las entrevistas se utilizó la técnica de saturación teórica. Análisis de contenido temático categorial con apoyo del software IRAMUTEQ.

ResultadosSe evidenció desconocimiento de políticas y términos por parte de los profesionales, confusiones conceptuales, asociaciones inadecuadas y un abordaje restringido de la prevención de las infecciones de transmisión sexual.

ConclusionesLa falta de capacitación refleja un abordaje cisnormativo y binario que compromete la asistencia a la población transexual. Persiste la falta de respeto al complejo social, resaltando la necesidad de educación permanente de los profesionales de salud, con el objetivo de una práctica asistencial inclusiva y respetuosa.

Not belonging to the dominant patterns of gender and sexuality, in addition to challenging social conventions, implies a series of limitations and questions about how society deals with the differences and individual needs demanded by those who do not fit the norms.1

The National Comprehensive Health Policy for Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals, Transvestites, and Transgenders was a milestone in the recognition of the needs and specificities of this population.2

Even with these achievements, transgender and transvestite people still face challenges in health service care at all levels of care, including in the outpatient clinics of the transgenderization process.2–4 The population has less adherence to the health system, mainly due to the discrimination they suffer when seeking care.5 Notions such as these emphasize the need for more outstanding establishment of trust between these people and health professionals, especially those who are in direct contact with the community, especially community health agents (CHA).6

Studies on care for trans people by nursing technicians (mid-level nursing professionals with technical duties) and community health agents (mid-level health professionals who connect basic healthcare services with the community), point to a generalization of care, lack of prioritization of care and an invisibility of the LGBTIQ+subject in primary care.6,7 These professionals play an essential role in the health of the community because, in addition to representing the link between it and the health system itself, they carry out activities in order to prevent diseases and promote health according to the guidelines of Unified Health System of Brazil (SUS).8

The objective of the study was to describe the practices and knowledge of Nursing Technicians and Community Health Agents of Primary Health Care about the transgender population.

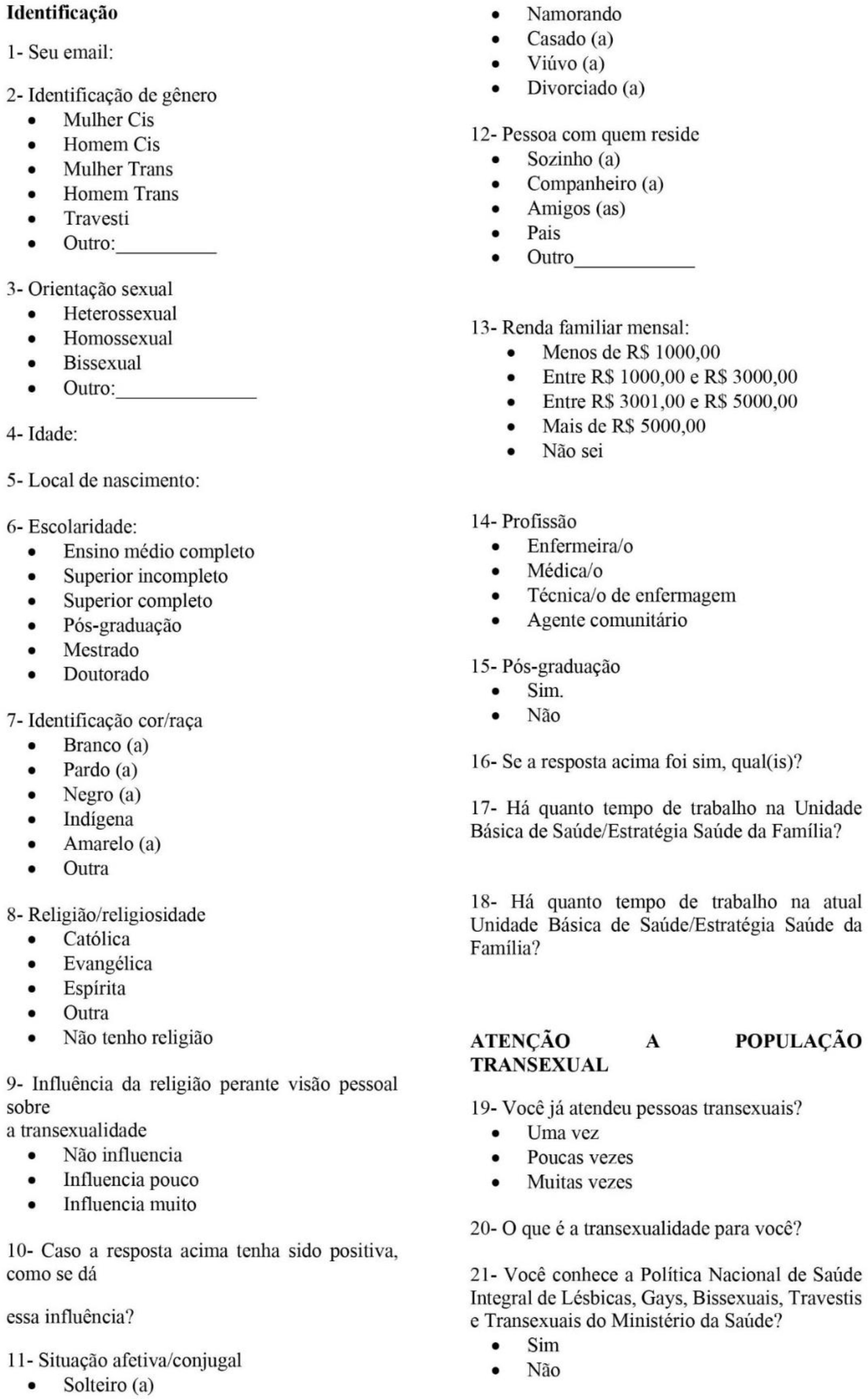

MethodsIt is descriptive research with a qualitative approach, as it values the speech of individuals, reflected by their social experiences.9 This text was prepared according to the Consolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ).10 The study was developed in a digital environment to send an invitation to participate, and the interview form was prepared in Google Forms (Fig. 1).

The participants were 18 Community Health Agents and 12 Nursing Technicians who worked in a Primary Health Care Units from several Brazilian states. They participated in the research and assisted transgender people at least once. The investigation took place during the period from January 2021 to February 2022. To capture the research participants, the sampling technique was used by chain indication or nets (snowball).11 From the indications, the research participants were contacted for an initial conversation about the study, and those who agreed to participate received a message with the link to the Google Forms form through WhatsApp or by email. This option was due to the social distance imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. The theoretical saturation technique was used to close the interviews.12

The data treatment of the online questionnaires was done using graphs divided into Excel spreadsheets, and the questions were opened by content analysis of the thematic-categorial type.13 In addition, the textual corpus was submitted for lexicographic analysis in the software Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires (IRaMuTeQ) using the word cloud method.14

ResultsThirty professionals participated in the research, 40% nursing technicians and 60% community health agents, with residents in greater concentration in the southeast region, followed by the northeast region.

Of the research participant group, 86.6% identified as cis women and 13.3% as cis men. Twenty-five participants identified as heterosexual, 3.33% as bisexual, 10% as homosexual, and 3.33% did not respond. Ages ranged from 21 to 55 years, with an average of 37 years. In terms of education, 36.66% have completed high school, 36.66% have incomplete higher education, 20% have completed higher education, 3.33% have postgraduate education, and one did not respond. Regarding race/color, 43.33% self-identified as Black, 30% as mixed-race, 23.33% as White, and one as Asian. As for religion, there was a diversification: 30% Catholic, 30% Evangelical, 20% Spiritist, 16.66% marked “other,” and 3.33% did not respond.

Regarding knowledge about the National Comprehensive Health Policy for Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals, Transvestites, and Transsexuals, only 3.3% of professionals claimed to be familiar with it. Additionally, only 23.33% of them have heard of the transsexualization process, while 76.66% reported that they had never heard of it.

The majority of participants stated that they do not feel any difficulty in attending to transgender people, and only 10% reported feeling some difficulty. The main actions cited by the interviewed professionals were: individual educational activity, participation in clinical and gynecological care, vaccination, dressing, hormone administration, as well as guidance on the flow of care in the Unit.

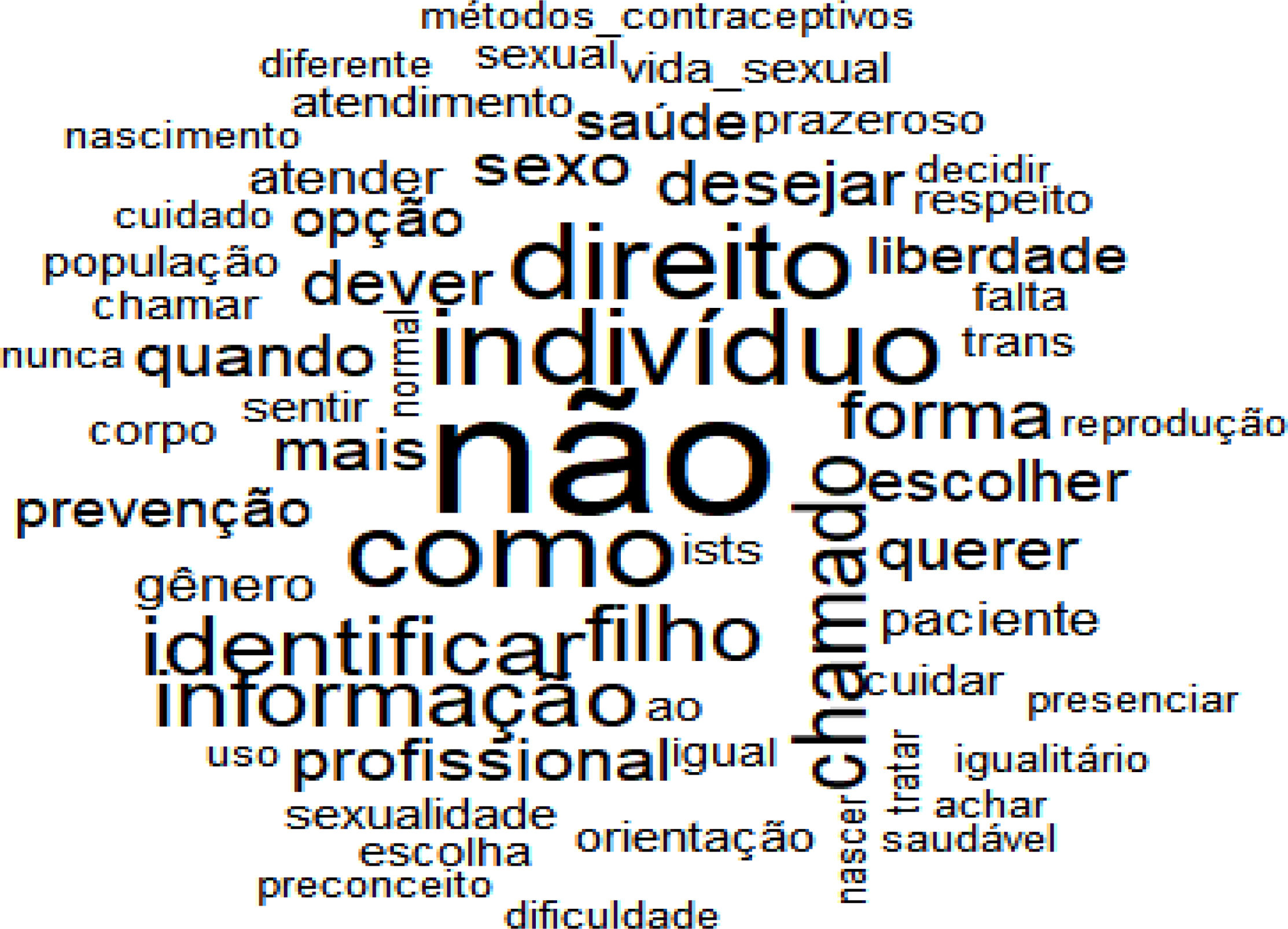

As a way of illustrating the results, the lexicographic analysis by IRaMuTeQ was used, which involves measuring the frequency and distribution of words in the textual corpus; thus, 2380 text segments were obtained, with 680 distinct terms, in which 410 appear only once. The software generated a word cloud, represented in Fig. 2.

The most evident word in the interviews was “no,” appearing 40 times, and the context in which it seemed the most was when the interviewees defined the concept of transgenderity, such as “not belonging to biological sex,” and when they referred to the idea of reproductive right, about the choice of “having children or not.” We highlight the word “right,” which was visualized 23 times in the corpus of the interviews when the interviewees talked about sexual and reproductive rights.

The word “information” appeared 16 times in diverse contexts when they reported that the problem lies in the lack of information from professionals and when they stated that disseminating information and training would solve the barriers between the transgender population and the SUS. In addition, other words were also highlighted, such as “identify,” “sex,” “duty,” “desire,” “child,” “professional,” “form,” “choose,” and “want.” Below is the discussion of the categories.

The analysis corpus consisted of 227 Units of Record and 14 Units of Meaning, which originated from 02 categories: Knowledge of professionals about the transgender population in health services and the de “cistematization” of the health system: building health for the trans population.

DiscussionKnowledge of professionals about the transgender population in health servicesThis category represented 53.9% of the corpus of analysis. It was noticed that some health professionals are unaware of the concepts of gender identity and gender expression. The way of dressing has no direct connection with gender identity; the binary clothing pattern is part of a social construction of the female and male gender. The gender structuring model is still assigned in a compulsory way (and not in a self-declared way), with an extreme relationship with the genitalia presented at birth.15,16 From there, binary categorization according to social gender norms begins.

The lack of resoluteness, professionals’ lack of knowledge about transgenderity, and disrespect and discrimination are reasons that contribute to the non-accessibility of services.4,17–19 The pathologization of transgenderity and the understanding of transgenderity as “non-biological” or abnormal was present in the participant group. It is crucial to note that the World Health Organization (WHO) promoted a significant conceptual review, relocating travestility and transgenderity from the category of mental disorder to the “Conditions related to sexual health,” being classified as “gender incongruence” in the international classification of diseases (ICD 11), which came into force in 2022.20 It is relevant to note that, despite this reclassification, transgenderity is still, in a way, categorized as a health condition inserted in an International Disease Code. This change reflects an understanding more aligned with mental health approaches and seeks to destigmatize the experiences of transgender people.

In that Regard, “the construction of itineraries is impacted by the relationship of trust and bond with the team, the depathologizing view of the service, and the lack of professionals capable of meeting the demands of trans people in private services”.21 There is a broad debate about the pathologization/psychiatrization of trans identities, which are understood as “wrong bodies” by society. This discussion and political struggle consider that it is society that is “wrong” for not respecting diversities and is consolidated in the STOP TRANS PATHOLOGIZATION 2012 movement – abbreviated STP 2012.22

The National LGBT Integral Health Policy in Brazil has guidelines and actions aimed at promoting, preventing, and recovering health care, promoting the reduction of differences arising from the barriers that are imposed on the LGBTIQ+population.2 In this study, only three participants claimed to know the policy; the document is little known by health professionals.8

This scarce knowledge extends beyond high school professional categories, as research with undergraduate students identified mistaken concepts about the transgender population, and university education was insufficient to respond to the integral demand of these individuals.23

Ordinance No. 2.803, of November 19, 2022, from the Brazilian Ministry of Health, redefines and expands the transgenderization process, including actions within the scope of primary care.24,25 It is a set of actions related to gender transition, such as hormonization, body and genital modification surgeries, as well as multi-professional monitoring. Even after thirteen years after its appearance, a majority of the professionals interviewed (76.6%) claim to have never heard of the transgenderization process. Gender transition is defined as the process in which transgender individuals live from the perception of their gender identity, involving a series of personal, social, and, in some cases, medical experiences to align gender expression with the felt gender identity.26 Transgenitalization, on the other hand, refers to the surgery to readjust the genitalia of trans people, that is, the surgical procedures to transform female genitalia into so-called male genitalia, or vice versa, and the non-performance of genitalia readjustment surgery does not delegitimize the gender transition, since it is optional to perform such surgery.27 The professionals confused the process of gender transition and transgenderization, as well as related transgenderity to the “sexual option.”

The term “sexual option” is no longer used, as it is understood that no individual consciously chooses their sexual orientation. In addition, there is a distinction between gender identity and sexual orientation, referring to the subject's personal gender identity and affective-sexual attraction, respectively. As seen in the study, the preservation of mistaken concepts predisposes the difficulty of self-perception of the fragility of care from ignorance.28

These findings lead to an analysis of how social processes and violence in non-cis-normalized bodies are also present in the health area.29 The perspectives of social exclusion of the trans population in this study are presented through ignorance and lack of motivation to qualify for assistance to the transgender population, as seen in this study.

There is still difficulty in the implementation of sexual and reproductive health in Basic Health Units, and this can happen due to “the diversity of actions and the difficulties of access that bump into prejudices and taboos, on the part of professionals”.30

Primary Health Care is one of the “gateways” to the SUS, being responsible for health promotion and disease prevention. Health care must take place outside the heterosexual and cisgender perspective. It is necessary to be aware of the transgender body and the particularities of each individual so that each service is adapted to that reality; there are men with a vagina, women with penises, pregnant men, trans lesbian women, etc.

Access to health services must be ensured comprehensively and universally. Therefore, professionals must be prepared to deal with diversity31 so that they have specific knowledge about terminologies related to transgenderity.32 Professionals express the need for training in relation to the theme and thus ensure adequate care and alignment with the needs of the transgender population.33 Constant awareness and awareness are fundamental to promoting an effective change in the health approach to this community. For example, disrespect for the social name is still a reality in health services. In addition to the social name, transphobia, the use of wrong pronouns, and the social reading of transgenderity as a disease are aimed at making it difficult for the trans population to access health services.34

A possible cause for this disrespect would be a personal non-acceptance based on social representations that directly influence the quality of the care provided.30 Attitudes like this are clear reflections of the transphobia present in society, which is “the prejudice that surrounds the transgender person and that can be materialized in the form of physical and/or psychological violence or the denial of rights”.35 All professionals interviewed declared to know what the social name is.

Transphobia and prejudice in health services, highlighting disrespect for the social name, are the main impediments to humanized care in health services.17 There is a structuring prejudice against transgender people in all social spheres, including health services, thus causing difficulty in identifying transphobia when practiced by co-workers, as when practiced by the professional himself.

The religion of the professional was pointed out as being a factor of discrimination. Certain religions preach an inappropriate ideology concerning transgenderity, understanding it as a deviation from normality that, at a specific moment, will return to the heterosexual and cisgender pattern with divine help. Such convictions promote a separation between singularized gender identities and self-declaration, being explicitly violent with the society that inhabits dissident bodies.36

To effect the de-systematization of health services, we need to combat the inequities and barriers between the transgender population and the SUS. According to the professionals interviewed, we can combat these barriers with awareness, lectures, debates, and respect, that is, with training. In this study, 76.66% did not do any training on this theme. Respect for the social name is crucial to providing humanized care. This reinforces the importance of inclusive practices highlighted by the interviewed professionals, corroborating the existing literature on the subject.

We considered as limitations of the study are the social distancing imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, which prevented conducting face-to-face interviews. Another limitation is the absence of transgender individuals working as healthcare professionals in the study field, as this would have provided better insight into transgender health for the participating professionals.

ConclusionsNursing technicians and community health agents have partial knowledge about transgenderity, and health care policies aimed at this population group. They bring a discourse of equality, of care without differentiation, and with respect. Still, there is a lack of knowledge of the concepts of sexuality, sexual orientation, and gender identity, which can harm health care.

Although they know the need to use the social name, disrespect for this right is still present, as well as the invisibility of care strategies already implemented for years in the public health system in Brazil. It can be seen that the service is guided by a cisnormative and binary perspective, not understanding the specific needs of the trans population, so permanent health education and a broad approach to gender diversity and sexuality in professional training are fundamental.

- •

Brazil has a Health Care Policy for LGBTIQ+people, which aims to expand the access of the population to sus health services, guaranteeing people respect and the provision of quality and resolution of their demands and needs.

- •

The transgender population has trouble in accessing health services, such as disrespect for the social name.

- •

The Transgenderization Process, instituted by the Ministry of Health of Brazil, presents a set of actions aimed at transgender people who wish to make body changes, from reception to hormones and/or surgeries, with actions within the scope of Primary Care.

- •

The results highlight gaps in knowledge about transgenderity among mid-level health professionals. This group is not included in most studies with health professionals, and it has a direct and continuous relationship with the population.

- •

It reinforces the importance of addressing gender and sexuality diversity in professional health training in an interdisciplinary way. These findings provide valuable insights for developing targeted educational strategies aimed at improving the understanding and practices of these professionals.

- •

The study highlights the importance of respect as a crucial facet of humanized care and suggests areas for improvement in care for transgender people.

- •

These contributions can guide health policies and clinical practices, promoting care environments that are more inclusive and sensitive to the needs of this specific population.

This research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro with opinion No. 4,211,411 and developed between January 2021 and February 2022.

FundingThe research article was developed with the support of the Research Support Foundation of the State of Rio de Janeiro – FAPERJ, Notice no. 14/2019 – support for emerging research groups in the state of Rio de Janeiro – 2019.

Article published with support from PROAP/PPGENF - UNIRIO.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

To the professionals who participated in this study, thank you for their availability. To nurses, Mariana dos Santos Gomes, Ana Carolina Maria da Silva Gomes, pedagogue, and transactivist Kathyla Katerine Valverde, thank you for contributing to the process of data production and reflective discussions on the subject.