Primary care physicians (PCP) are in a privileged position to monitor children's neurodevelopment during preventive health care visits.1 In Portugal, a screening programme for neurodevelopmental disorders (ND) in primary health care was established in 2008, using the Modified Mary-Sheridan Developmental Assessment Scale.2,3 This tool, available in electronic version for quick consultation and filling, allows the comparison of the child's abilities with those expected for his age and the detection of alarm signs by age group.3–5 In 2012, the use of the Modified Checklist for Autism Toddlers (M-CHAT) was also advocated, allowing early detection and guidance of at risk-ASD patients between 16 and 30 months.2 Despite the increasing awareness concerning ND, current evidence suggests its underdiagnosis. A reflection on the adequacy of the PCP referrals for neurodevelopmental pediatric consultations becomes relevant. Our aim was to analyze the match between primary care referral reasons and the final diagnosis established at neurodevelopmental consultations of a pediatric tertiary hospital.

MethodsObservational and retrospective study, enrolling patients referred to the neurodevelopmental unit of a pediatric tertiary hospital by primary care physicians from January to December of 2021. Data was collected of patients’ electronic clinical files. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics 25.0.

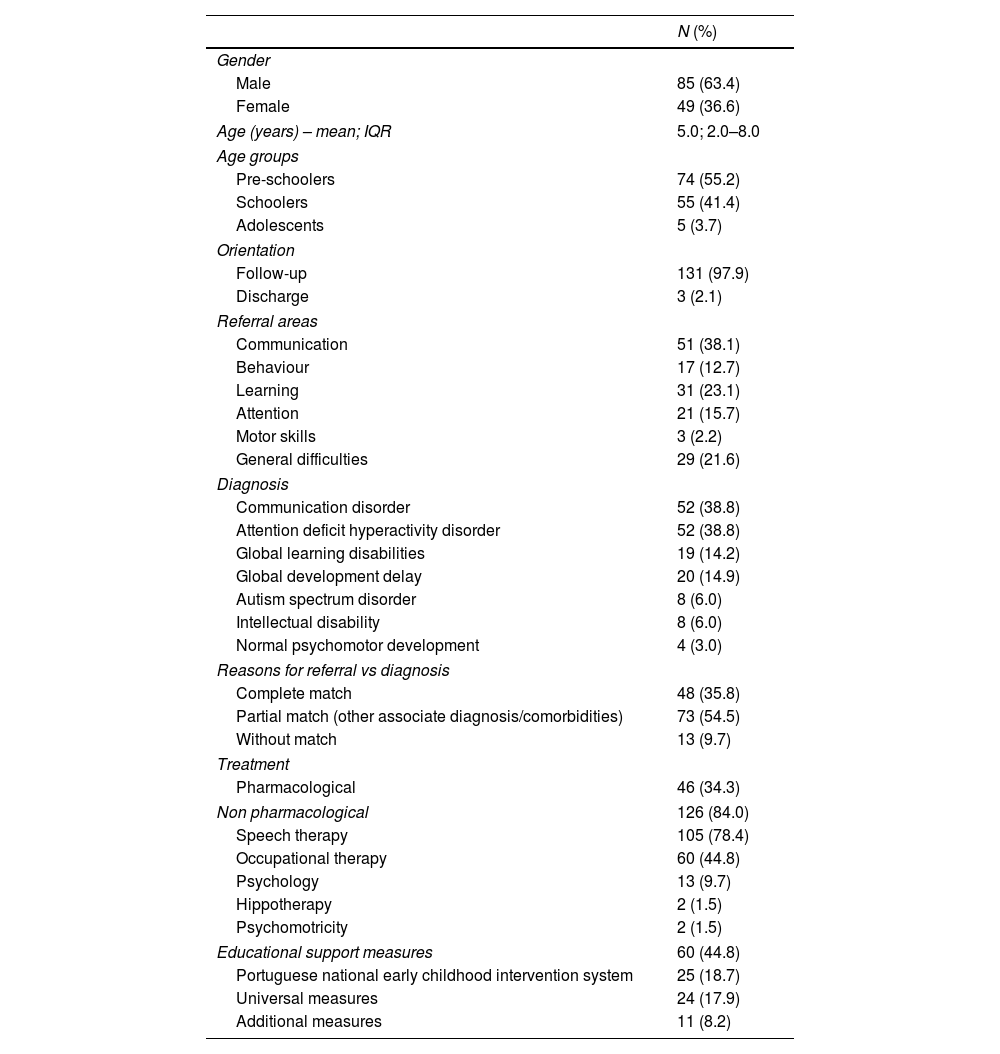

ResultsA total of 134 consultations were performed. 85 (63.4%) patients were male. The median age at time of referral was 5.0 (interquartile range (IQR): 2.0–8.0) years. Seventy-four (55.2%) children were pre-schoolers (1–5 years old), 55 (41.4%) school-aged (6–10 years old), and 5 (3.7%) adolescents.

The referral reasons were grouped in communication [51 (38.8%)], learning [31 (23.1%)], attention [21 (15.7%], general [29 (21.6%)], behaviour [17 (12.7%) and motor concerns [3 (2.2%)]. In 29 (21.6%) children three or more developmental domains were worrisome.

The final diagnosis at neurodevelopmental consultation were communication disorder [52 (38.8%)]; attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [52 (38.8%)]; global learning disabilities [19 (14.2%)]; global development delay [20 (14.9%)] and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [8 (6.0%)].

When comparing reasons for referral with final diagnoses we found a match in 48 patients (35.8%). In 73 (54.5%) there was an agreement between PCP concerns and the neurodevelopmental diagnosis, but other associated disorders/comorbidities were found. In 13 children (9.7%) there was not an overlap between the referral cause and the final diagnosis.

Forty-six patients (34.3%) started pharmacological treatment and 126 (84.0%) nonpharmacological therapies. Sixty (44.8%) were eligible for educational support measures and 25 (18.7%) for intervention by the Portuguese national early childhood intervention system.

All the sample characteristics are in Table 1.

Summary of sample characteristics.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 85 (63.4) |

| Female | 49 (36.6) |

| Age (years) – mean; IQR | 5.0; 2.0–8.0 |

| Age groups | |

| Pre-schoolers | 74 (55.2) |

| Schoolers | 55 (41.4) |

| Adolescents | 5 (3.7) |

| Orientation | |

| Follow-up | 131 (97.9) |

| Discharge | 3 (2.1) |

| Referral areas | |

| Communication | 51 (38.1) |

| Behaviour | 17 (12.7) |

| Learning | 31 (23.1) |

| Attention | 21 (15.7) |

| Motor skills | 3 (2.2) |

| General difficulties | 29 (21.6) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Communication disorder | 52 (38.8) |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 52 (38.8) |

| Global learning disabilities | 19 (14.2) |

| Global development delay | 20 (14.9) |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 8 (6.0) |

| Intellectual disability | 8 (6.0) |

| Normal psychomotor development | 4 (3.0) |

| Reasons for referral vs diagnosis | |

| Complete match | 48 (35.8) |

| Partial match (other associate diagnosis/comorbidities) | 73 (54.5) |

| Without match | 13 (9.7) |

| Treatment | |

| Pharmacological | 46 (34.3) |

| Non pharmacological | 126 (84.0) |

| Speech therapy | 105 (78.4) |

| Occupational therapy | 60 (44.8) |

| Psychology | 13 (9.7) |

| Hippotherapy | 2 (1.5) |

| Psychomotricity | 2 (1.5) |

| Educational support measures | 60 (44.8) |

| Portuguese national early childhood intervention system | 25 (18.7) |

| Universal measures | 24 (17.9) |

| Additional measures | 11 (8.2) |

Neurodevelopmental disorders are an heterogenous group of disorders, characterized by deficits that impact child's functioning at personal, social, academic and occupational levels. A high index of suspicion for these prevalent disorders in primary care setting is crucial to allow early detection of children with criteria for further evaluation and the establishment of adequate diagnosis and personalized intervention.

In our study, we found that most of the neurodevelopmental diagnosis matched, at least partially, the referral concerns. However, there was also a high rate of comorbid conditions that were not previously considered. We highlight the need for continuous training for PCP, focusing not only on normative neurodevelopment and its variants, but also on the clinical manifestations of the diverse neurodevelopmental pathologies, keeping in mind that comorbidity is the rule rather than the exception in neurodevelopmental disorders.

Ethical considerationsThis study was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital where it was carried out. There is no objection the data described in the study. The patients involved have given their consent.

FundingThe study did not receive funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.